by Yona Zeldis McDonough

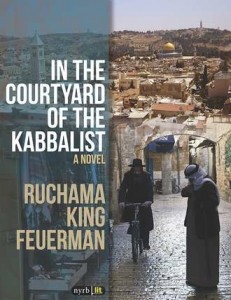

In the Courtyard of the Kabbalist

Born in Nashville, TN and raised in Virginia, Ruchama King Feuerman bought herself a one-way ticket to Jerusalem when she was seventeen to study Kabbalah with mystics. She went to college in Israel and returned to the United States to get her MFA at Brooklyn College. The stories she wrote there became Seven Blessings, her acclaimed first novel about matchmaking from St. Martin’s Press; Kirkus Reviews called her, “The Jewish Jane Austen.” Today she lives in New Jersey with her husband and children where, among other things, she runs writing workshops for Orthodox and Hassidic women; she talked to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about the lure of the Talmud, the people she met in Israel and her abiding belief in the power of the story.

Yona Zeldis McDonough: Tell me about the time you spent in Jerusalem.

Ruchama King Feuerman: The ten years I lived in Israel – nine of them in Jerusalem – I fell in love with Torah study. Chumash, midrash, philosophy, Maimonides, law, the works. I loved the act of throwing myself at the text, beating my brains to figure out what Jewish thinkers had thought centuries ago, touching their minds. This was in the eighties when a whole revolution was taking place in Orthodox women’s Torah study. I tutored and taught at Brovender’s, perhaps the first school to teach women Gemara. After six or seven years, though, I started to feel like a walking brain. I found myself craving a more Hassidic type of learning. I met kabbalists, I prayed with the Hassidim, and I studied the Hassidus of Breslev, Chabad, Chernobyl, whatever I stumbled upon. I loved how if there was a great rabbi or rebbetzin you wanted to talk to, you could just get on a bus and go meet them. I loved the many wise and powerful Jewish women I met there with their artistic head scarves. Jerusalem seems to breed them. Three decades later, I can’t stop writing about Jerusalem, the personalities I met there. YZM: Why did you return to the United States?

RKF: There was a battle within me – to be a Torah teacher or to be a writer. As long as I was in Israel, I knew Torah would prevail. There is something in the Jerusalem air that draws one toward Torah. After ten years, I realized I wanted to be a writer more, and that my writing could only take root here in the States. I remember my last day in Israel. I felt as though my womb had been ripped out of me.

YZM: Your first novel, Seven Blessings, was about matchmaking in the Jewish community; can you say more?

RKF: For me, the motif of matchmaking is irresistible. It’s so much more than boy meets girl, especially when it’s overlaid within a religious framework. It’s lineage meets lineage, destiny meets destiny. There are so many moving parts, so much depth and drama that is staked on these outcomes.

For a year, I lived in the home of a famous Jerusalem matchmaker. I’d come home from work and see shidduchs – blind dates – in various states of progress in her living room. She shared her secrets of the trade with me, even as she tried to set me up on blind dates. I saw her own marriage up close. You know, when we think of matchmaker, our minds naturally turn to farce, yenta, double-chinned bubbes stirring vats of chicken soup. I thought it was time to freshen up the image, let matchmakers be real people, with all their angst, intellect, and private yearnings.

But I was drawn to matchmaking as metaphor, too. One of my matchmakers, Judy, embarks on a journey of rigorous Torah study, of intellectual inquiry, for the first time. She observes that all of life is a shidduch, a match, “a shidduch to get the right fit between neighbors, to reconcile between friends and parents and children, between husbands and wives, to reconcile one country to another. The whole world was a shidduch. And she was on a shidduch, too, if she dared, with her self.” Maybe that is the ultimate match, achieving that intimacy with your own mind and soul.

YZM: What was the inspiration for your newest novel, In the Courtyard of the Kabbalist?

RFK: When I was in my twenties, I became enamored with kabbalists. There was one in particular who was popular with my friends. By the time I decided to seek him out, though, the elderly rebbe had become sick and stopped seeing people, but I thought I’d weasel my way in. There was a wonderful anything-goes atmosphere in the kabbalist’s courtyard. It attracted Yeshiva students, a hot shot Arab lawyer plagued by ghosts, a soap opera actress, depressed matchmakers, politicians, abusive rabbis, people from all corners of Israeli society. I got to talking with the kabbalist’s assistant, a short, bearded man with a nasal voice. His words to me were shocking, brilliant, bordering on the psychic. The man struck me as having real kabbalist potential.

I became fascinated by the middle-aged assistant. What kind of life circumstance would bring a person to this job, this calling? And did the assistant have ambitions to be more than just a helper? I wanted to know about all the people who surrounded the kabbalist, protected his aura. I was curious about his wife. Was she down-to-earth or ethereal? Did she resent the mob that took over her home or maybe have her own aspirations to kabbalistic greatness? I never met the kabbalist’s wife, but a story began to spin.

And then there’s Mustafa. For many, he’s their favorite character. I was curious what would happen if I would bring together two people from the corners of Israeli society, a deformed Arab janitor and a kabbalist’s assistant whose deformities, one might say, are on the inside. Might something new happen here? Or did the repetitions of an ancient conflict pre-ordain every interaction between Jew and Arab? I had to see for myself.

As for the kabbalist or the rebbe, I eventually did get to see him. We actually laughed together. It may sound odd but it was the best moment of my life. For years afterward, whenever I needed a lift, I would remember our co-mingled laughter—and it sustained me. I think I wrote In the Courtyard of the Kabbalist in order to relive that laughter, to re-experience the courtyard and the seekers I met there, and the seeker I was then.

Someone recently asked if I considered myself anything like the main female character, Tamar, a twenty-something seeker who rides a Vespa and is a beauty besides. I had to say no.

YZM: The character of Tamar plays a pivotal role between Isaac and Mustafa; do you see her as the mediator the between Jews and Arabs?

RKF: Truthfully, Tamar doesn’t have the dimension of the Israeli-Arab conflict within her. She’s not a small person, but her battlefield is basically limited to her womanhood and spirituality, and it doesn’t have real ripples for larger political/religious questions. My characters aren’t so ideologically driven. They are deeply involved in their own lives, but they also care about the people around them, like Mustafa. Sometimes, just to care is to already be a mediator.

YZM: You have four children; how do you balance the writing life with all the other demands on your time?

RKF: I don’t balance. I’m horrible at it. Every six months, I’ll set rules for myself. No answering the phone or going near the computer between 4-9 pm when the kids are around, awake, need me. That’ll last a month or two, but then I creep back to my old obsessive writing ways.

YZM: Tell me about the writing workshops women that you run.

RKF: It’s a multi-layered, many-pronged effort. I poke from all sides. First, expose them to high-level writing. Then I trick my students into writing. Bring them to a point where they don’t care how awful they sound. That’s when the best stuff comes out. Then I do the opposite — break down the process into components, bite-size attainable bits. There’s the craft and there’s the unconscious. I try not to ignore either. In the end, though, the stories come out when the writer realizes she’s on a journey. With me, with her work, with her inner process. Many of my students have stayed with me for years. People are engaged in some kind of journey with themselves. It’s not as if they’re trying to learn how to fix the radio or carburetor. They’re arranging for a dance of the imagination.

Who comes? Jewish women, mostly. I lead workshops on the phone and in person. They call in from England, Israel, Canada, Switzerland and America. Some have Ph.D.s in esoteric subjects while others have never gone beyond high school. Some have MFAs from Columbia and others never took a writing course. I love the pleasure these women take experience in each other’s company. It’s a kind of club where your outer accomplishments or good deeds or status don’t matter. The only thing that counts is: Can you tell your story? I especially enjoy working with Hassidic women, ladies who haven’t gone to college, who initially feel a little insecure. In the end, we are all humble and equal before the power of the story.