The Lilith Blog

February 4, 2014 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

What DID Nora know?

Linda Yellin is a funny lady. To wit, her new novel, What Nora Knew,” is crammed with snappy one-liners, snarky apercus and a whole lot of good-humored sass. Whether intentionally or not, Yellin has joined ranks with Ephron in turning out a particular kind of humor, one that is specific—if not unique to—Jewish women. She talks to Lilith Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about concealed vibrators, the enduring appeal of rom-coms and the nuances that separate the funny girls from the boys:

Linda Yellin is a funny lady. To wit, her new novel, What Nora Knew,” is crammed with snappy one-liners, snarky apercus and a whole lot of good-humored sass. Whether intentionally or not, Yellin has joined ranks with Ephron in turning out a particular kind of humor, one that is specific—if not unique to—Jewish women. She talks to Lilith Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about concealed vibrators, the enduring appeal of rom-coms and the nuances that separate the funny girls from the boys:

Yona Zeldis McDonough: You have a background in advertising; how did you transition to writing fiction?

Linda Yellin: I’m sure there are people who’d say advertising is fiction, but that theory aside, my first novel was ninety percent true. So it was only sorta-fiction. I changed all the main players’ names to keep my relatives from getting mad at me. I didn’t want to get un-invited to the family seders.

The next book, The Last Blind Date, was a memoir, so that was technically non-fiction. But I guess none of my cousins got offended because they’re still speaking to me. What Nora Knew is a novel, although Nora Ephron and her movies and insights are real, so I guess I’m still transitioning into writing fiction.

YZM: Your protagonist, journalist Molly Hallberg, has had some pretty entertaining assignments: learning to dance like a Rockette and sneaking vibrators through security scanners. Any of these drawn from real life experiences?

LY: Absolutely. Molly and I have a lot in common. Most of her assignments are ones I’ve done for MORE magazine. Including one where she spends a day wearing kegel underpants. (One-inch silicone plug in the crotch…you can figure out the rest.)

The vibrators was my favorite assignment. There were three of them – all “disguised” like cosmetics: a lipstick; a mascara; and a blusher brush. I stood in line at the Family Court building in New York thinking: it’ll be really great for the story if I get busted for doing this. (Security guard: “Would the owner of the vibrating mascara please step out of line?”) But all along I was praying that I’d pass through. When it got down to story-versus-mortification, I was more afraid of mortification. Molly Hallberg’s braver than me.

YZM: What Nora Knew is an homage not only to Nora Ephron but to the whole Hollywood tradition of romantic movies. Can you say more about that?

LY: There are certain constructs and expectations in romantic movies. We probably know from the get-go who the heroine will end up with, but if you care about the characters, you want to travel along with them and root for their success. Whether it’s Meg Ryan and Tom Hanks, or Meg Ryan and Billy Crystal, or Jennifer Lawrence and Bradley Cooper – romantic comedies are journeys with happy endings, and who doesn’t love that? And who doesn’t love Nora Ephron’s romantic comedies?

YZM: Do you consider Ephron a quintessentially Jewish humorist and if so, why?

LY: Her humor is quintessentially relatable, so it also covers Christianity, Buddhism, Atheism; you name it. But there is a wry, sardonic point-of-view in all of Nora Ephron’s writing that certainly feels Jewish. An oy-vey-can-you-believe-this quality. It’s the same one I grew up with while my aunts and uncles and cousins were debating life over corned beef and smoked fish.

YZM: How would you describe the differences between male and female humorists?

LY: Subject matter. Our humor leans toward relationships and emotion. Guys tend to vamp more on guy-stuff. Sex, sports, things that explode. Don’t hold me to this opinion, though. For sure, there’s a PhD candidate out there whose doctoral thesis would totally disagree.

YZM: What, in the end, did Nora know?

LY: Plenty. That’s why it was so much fun to write this novel.

- No Comments

January 30, 2014 by Sarah M. Seltzer

Obscenity and the Feminist Case for Free Speech

In his new book Unclean Lips (find an excerpt in Lilith’s Winter 2013-2104 issue) Josh Lambert, academic director of the Yiddish Book Center, traces the history of Jew and obscenity in America, which which has in the past been treated gingerly because of problematic stereotypes. Yet Lambert writes that in each epoch of free speech and obscenity debates, Jews have been involved for different contextual reasons relating to our status in America and the mores of the time. He talked to Lilith about feminist depictions of prostitutes, Sarah Silverman, birth control and censorship, and modern-day modesty crusaders.

In his new book Unclean Lips (find an excerpt in Lilith’s Winter 2013-2104 issue) Josh Lambert, academic director of the Yiddish Book Center, traces the history of Jew and obscenity in America, which which has in the past been treated gingerly because of problematic stereotypes. Yet Lambert writes that in each epoch of free speech and obscenity debates, Jews have been involved for different contextual reasons relating to our status in America and the mores of the time. He talked to Lilith about feminist depictions of prostitutes, Sarah Silverman, birth control and censorship, and modern-day modesty crusaders.

Sarah Seltzer: Where did your interest in obscenity in a Jewish context came from? Was there one writer or artist who provided the doorway to the topic?

Josh Lambert: Basically it was reading Philip Roth, and finding myself compelled by his twin obsessions with Jewishness and obscenity. Then, my grad advisor asked me to read Adele Wiseman’s Crackpot, an amazing novel that not nearly enough people have read or discussed. And I felt like I had another side of the story.

SS: Crackpot! You write that it posits its prostitute protagonist, and her decision to allow her son to sleep with her unknowingly, as a feminist alternative to the Portnoy’s Complaint narrative. Do you think that the novel’s feminism mixed with its taboo subject is why it has faded while Portnoy and its ilk flourished?

- No Comments

January 29, 2014 by Chanel Dubofsky

It’s Always a Scene at the Clinic

Image via The Clinic Vest Project

I. At the clinic, there is the usual bank of protesters at the curb, holding pictures of white skinned Jesus and white skinned babies, along with large crosses. They’re praying loudly in Spanish and English. It’s a scene. It’s always a scene. The protesters in the front and back, and us, in our orange vests, watching, opening doors. Sometimes people ask us if we get paid to stand there. The protesters refer to us as “Satan.”

II. H is a friend of mine who lives in Los Angeles, where he writes and makes tv shows and escorts at a clinic. We talk about how this week, the Supreme Court is taking up McCullen vs. Coakley, a lawsuit against a 2007 Massachusetts law stating that anti-abortion protesters must remain behind a yellow line painted on the sidewalk, preventing them from interacting with patients and staff entering the clinic. We talk about Occupy LA and Occupy Wall Street, how brigades of police officers followed protesters and journalists everywhere, looking for any excuse to arrest them. H says, “Law enforcement and legal communities are not exactly clamoring to expand the liberties of those protesting against capitalism or racism, but protesters trying to destroy women’s lives is okay. It’s bullshit.”

III. One Saturday, a young man with a hipster beard, wearing corduroys, called to a woman entering the clinic, “You don’t have to do this, you know.” P, another escort, put his body between the young man’s and hers and walked her to the door. Later, the same young man leads a church group from Texas in a truncated version of the exorcism prayer, which I recognize from horror movies.

IV. Sometimes, while we’re watching the protesters, we talk about why we come here, why we do this. P says it’s because he can see the result immediately- the patient needs health care, there’s this obstacle of the protesters, you get the patient to the door, you’ve done something. I say it’s because I’m angry, which is the truth, but also, it’s thicker than anger.

V. Shrinking the buffer zone, or getting rid of it all together, would mean that the young man who did the exorcism, and the folks praying on the curb, and the monks who gather at the back of the clinic and follow people who walk out down the street, could get as close to the patients and the clinic staff and the escorts as they want. This means hands that grab and push pictures of “aborted” fetuses at people who are about to undergo a medical procedure, whether that’s an abortion or a pap smear. (If you’re questioning whether or not this “counts” as an act of intimidation or violence, consider if you would want to be in the same situation. If you would like to find out how you’d feel.) In RH Reality Check’s Legal Wrap, Jessica Mason Pieko wrote, “the underlying question…. Just how much violence against women is constitutionally permissible?”

VI. In the United States, we are not sure about women. We’re suspicious. We’re not sure if women think about things. We’re not sure if they deserve space, or trust, or agency. We’re not sure if women are human.

- 1 Comment

January 28, 2014 by Erika Dreifus

A Not-So-Modest Proposal: Add Another Matriarch to the Mix

“Moses and Jochebed” by Pedro Américo, 1884.

We honor four biblical “matriarchs”: Sarah, Rebecca, Leah and Rachel. And they’re important, even if we recognize them mainly, if not solely, for the sons they birthed.

But they weren’t always admirable. Take Sarah’s treatment of Hagar and Ishmael. Or Rebecca’s devious plan to trick her husband into giving their son Esau’s birthright to their other son, Jacob. True, Jacob got his comeuppance when Leah, disguised as the sister he wanted to wed, married him in Rachel’s place. As for Rachel, it’s hard to know what actions she might have taken, had she survived Benjamin’s birth. We do know that she was susceptible to jealousy.

For these reasons—plus others I’ll list shortly—I propose that we add a fifth matriarch: Jochebed.

I’m not unbiased. “Jochebed” is my Hebrew name (after my mother’s maternal grandmother). As a child, I learned that we (my great-grandmother and I) shared this name with a biblical foremother. But all I knew about the original Jochebed, gleaned from Bible Stories for Jewish Children, was that 1) she was the mother of Moses and his also-impressive siblings, Aaron and Miriam, and 2) she saved Moses’s life by setting him afloat for Pharaoh’s daughter to discover and adopt.

- 2 Comments

January 23, 2014 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Who are the fools here?

The expression still waters run deep could have been coined for Joan Silber. In person, she is charming, modest and even self-effacing; on the page, she bristles with feeling–humor, anger and lust are just part of her impressive range—and her capacity for creating sympathetic, likable characters who nevertheless do some highly unlikable things is one of her greatest gifts. In a conversation with Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough, Silber shares some of what she’s learned over her long and rich writing career.

The expression still waters run deep could have been coined for Joan Silber. In person, she is charming, modest and even self-effacing; on the page, she bristles with feeling–humor, anger and lust are just part of her impressive range—and her capacity for creating sympathetic, likable characters who nevertheless do some highly unlikable things is one of her greatest gifts. In a conversation with Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough, Silber shares some of what she’s learned over her long and rich writing career.

YZM: Let’s talk about the concept of linked stories. What does this form allow that others don’t? How does such a book differ from a novel or a more conventional story collection?

JS: This is the third book of linked stories I’ve done. There are lots of things I love about the form. It lets me treat material from different angles–a minor character in one is major in another—and I can work different sides of a theme. In this book, for instance, we see the dilemmas in being a fool for an idea, and the disadvantages in not being one.

Linked stories used to be considered an apprentice form, written by writers who really wanted to do novels. (Not true for me–I’d done three novels first.) Now it has its own popularity—there are definitely more linked collections around.

One of my favorite things about the form is that characters who are dislikeable in one story can be humans we’re allied with in another. (Liliane, for example.) There’s a beautiful quote from John Berger in which he says, “Never again shall a single story be told as if it were the only one.”

- No Comments

January 21, 2014 by Michelle Brafman

What We Don’t Talk About When We Talk About Hair

“You’re going to talk about hair? For two hours?” my mother said after I told her I’d been invited to co-facilitate a Lilith Salon, part of a series of discussions held at hundreds of locales throughout the country, including theaters, synagogues, and private homes. My mother then proceeded to talk about her hair for a good fifteen minutes, and we could have kept going.

“You’re going to talk about hair? For two hours?” my mother said after I told her I’d been invited to co-facilitate a Lilith Salon, part of a series of discussions held at hundreds of locales throughout the country, including theaters, synagogues, and private homes. My mother then proceeded to talk about her hair for a good fifteen minutes, and we could have kept going.

On a balmy winter’s night, I headed down to the Sixth and I synagogue in Washington, DC for more hair talk with the Not Your Bubbe’s Sisterhood, a group of urban women in their twenties and thirties. I struck up an easy conversation with a redhead with perfectly sculpted curls and big green eyes. She credited a specific “product” for her gorgeous locks and offered a few suggestions about which one might work for my curls. Hair is the ultimate icebreaker for women.

We settled into a circle of folding chairs, and Susan Weidman Schneider, our lead-facilitator, asked the group to share stories about their hair. The curly girls talked about the gyrations they go through to manage their hair: timing of the washings, hunting down expensive products to avoid frizz, or cringing when boyfriends run their fingers through their hair and in turn wreak havoc on their “dos.” Susan described us as “a secret sisterhood of curly-haired women.”

We all commiserated about the power and pall of a “bad hair day.” Many heads shook in agreement to tales of the sweet maternal moments of braiding and combing as well as our mothers’ edicts to not cut/grow/straighten/perm our locks. Clearly attitudes about hair and beauty ripple through generations, and one super smart woman articulated the idea that conversations we have about our hair mirror our hormonal, emotional, social, and developmental stages in life. She was spot on. When we talk about hair, we’re talking a whole lot more than gels and bad perms.

I was struck by one straight-haired woman’s irritation with people who assumed that because she didn’t have “Jewish hair,” she wasn’t Jewish. As a teen, I desperately wanted to unload my Jewish hair. I’d spent my early childhood in an intense Jewish community, and I found the escape into a secular world alternately terrifying and freeing. I wanted hair that feathered, like Dorothy Hamill or David Cassidy’s or a long blonde mane that swished when I walked. Before bed each night, I showered and braided my wet hair so that my waves would have some predictability when I awoke the next morning. I didn’t wear a cap during swim practice so the chlorine would lighten my hair (it did, to the color of dried mud).

I’ve since made friends with my curls, but now I have a host of new hair-related concerns, some pertaining to my role as a mother. I am a liceaphobe, albeit recovering. I cringe when I hear the expression “nitpick,” and I once heard my daughter tell a playmate that they could not share their American Girl Dolls’ brushes. All of the salon women agreed on the overall disgustingness of microscopic eggs feeding on blood drawn from the scalp. Most of the women, however, had yet to experience their first memo from their child’s school nurse and the resulting nuisance of lice combs, endless loads of laundry, and pesticides and/or the embarrassment of their little one being cast as the Typhoid Mary of head bugs (reminiscent of crabs and other communicable issues that circulated through college dorms).

I have certain friends with whom I’ve discussed our evolution from a henna, to semi-permanent dye, to permanent dye, to monthly coloring. Others have decided to go gray, and we talk about that too, and for a few hours after we’ve chatted, I swear I’ll stop exposing myself to hair dye toxins (and Diet Coke while I’m at it). My vanity wins out every time. The Not Your Bubbe’s Sisterhood women complained about bushy eyebrows that colonize their foreheads, while my friends submit to using a pencil to fill in the sparseness. We’re saying a slow goodbye to the follicular bounties of our youth, and a tentative hello to the beauty that comes from grace, acceptance, and the growing awareness that life is fragile.

- No Comments

January 20, 2014 by Elizabeth Mandel

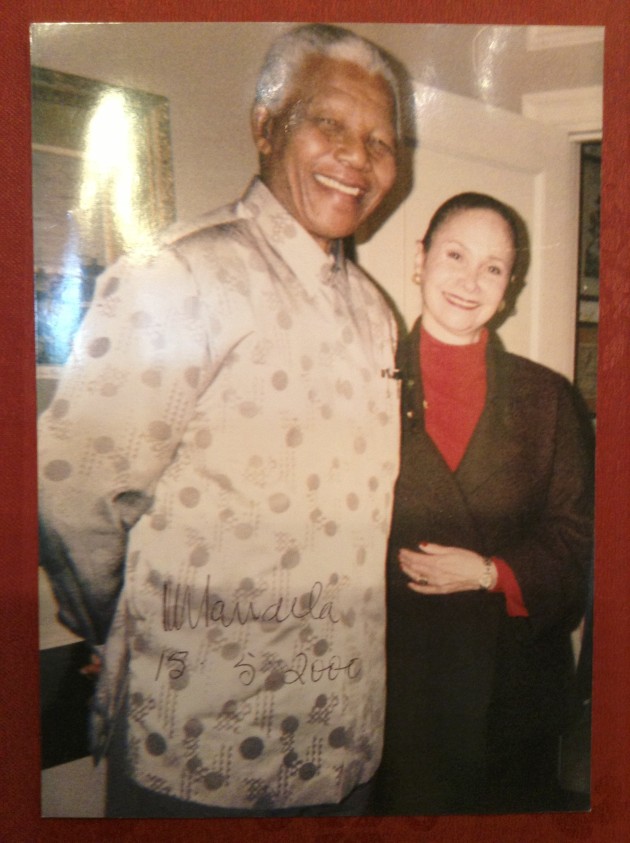

King & Mandela

The arrival of Martin Luther King Day six weeks after the death of Nelson Mandela naturally invites discussion of equity and equality. At home, with our daughters, we are reinforcing the lessons Dr. King and Mr. Mandela taught the world. In addition to our family discussions, our daughters are fortunate to have a grandmother who met with Mr. Mandela personally. I look forward, as the girls grow older, to them discussing that experience in depth with my mother, Harriet Mandel.

In the meantime, in memory of Mr. Mandela and in honor of MLK Day, I share below my mother’s memories of those meetings:

Harriet Mandel and Mr. Mandela

With his dazzling smile and twinkling eyes, radiating warmth, charm, and charisma and dressed in a signature boldly patterned shirt, Nelson Mandela strode into the room for our meeting. It has been 13 years since I had the uncommon privilege of engaging in extended conversations with Mr. Mandela, but the memories remain powerful as ever.

Nelson Mandela’s story made my spirits soar as he led South Africa in its dramatic journey from apartheid to democracy. Along with the rest of the world, I tracked this life lived on the highest planes of human fortitude, endurance and purpose. We longed for the release of this indomitable spirit from prison, and were exhilarated by his example in freedom. Imagine how I felt when an opportunity came for me to meet this luminous hero.

In the year 2000, South African Ambassador to the United States Sheila Sisulu introduced me to Nelson Mandela. Through my career in international diplomacy and Jewish community relations, I had come to know Mrs. Sisulu when she served as South Africa’s Consul General in NYC from 1997-1999. We were guests in each other’s homes (I had the honor of hosting her in ours for Shabbat dinner) and our professional relationship developed into a personal friendship. Mrs. Sisulu was a lifelong activist for educating and empowering the underprivileged, and a civil rights supporter who fought against apartheid. She was also the daughter-in-law of Walter Sisulu who, together with Mr. Mandela, founded the African National Congress’ (ANC) military wing, and served at the same time as Mr. Mandela in Robben Island prison. In 1999, she was personally appointed by Mr. Mandela as the first black person and first woman to represent South Africa as the country’s ambassador to the United States.

In 2000, Mr. Mandela was in the process of establishing the Nelson Mandela Foundation, with the mission of promoting dialogue to resolve global conflicts. He was deeply invested in exploring a resolution to the Arab-Israeli conflict, and planned to come to New York City to speak with “New York Jewry” to garner support for his Middle East peace plan. Mrs. Sisulu asked me to arrange for a meeting between Mr. Mandela and Jewish community members. She also asked that, given the controversial nature of the subject, Mr. Mandela and I meet first for preparatory discussions.

This came against the background of complicated relationships between Mr. Mandela, Israel and the Palestinians. Israel maintained close military ties with apartheid South Africa until the end of the regime. Mr. Mandela, long associated with national liberation causes, was supportive of the Palestinians, and critical of Israeli policy towards them, though he did publicly support Israel’s right to exist. Neither Israel nor the Palestinians gave much support to his plan (which each thought was either to simplistic or too excessive), but Mr. Mandela was determined to make his case, and forged on.

In the first half of 2000, Mrs. Sisulu arranged two extended one-on-one conversations between Mr. Mandela and me, both times in his suite at the Waldorf Astoria. I vividly remember Mr. Mandela walking into the room for the first time. My immediate thought was, here is a prince – which indeed he was. I later learned that he was the son of Chief Henry Mandela of the Madiba clan of the Xhosa-speaking Tembu people. He had relinquished his claim to the chieftainship to become a lawyer. He radiated grace, dignity and energy, yet was surprisingly down to earth. He unhesitatingly embraced me in a warm, welcoming hug and joked that Mandela and Mandel were destined to meet.

It was a rare honor to spend hours talking with this noble man, but it also felt relaxed and comfortable. In fact, it was truly remarkable, and a testament to the greatness of this global hero, that he put me so at ease and that our conversation flowed as if we were long time friends. Mr. Mandela’s charisma was exhilarating, but it was his obvious respect and consideration for the opinions of others – in this case, a stranger’s – that left a lasting impression and underscored his distinctiveness.

We spoke casually for a while, and then turned to the purpose of the meeting. Mr. Mandela noted that he was aware that his sympathetic views towards the Palestinians would probably not find a welcome audience in the Jewish community. However, he wanted to engage this group because he believed that the American Jewish community’s understanding of his peace mission would promote his cause in Israel. He asked that I give him background on and insight into the American Jewish community to help him communicate in resonant ways.

My background is in international affairs, with a specialization in the Middle East, and I had spent my professional life dealing with global leaders on this issue.. But Nelson Mandela was in a league of his own, and I was humbled by my challenge. Rather than express my personal opinion on the complex issue of Israeli-Palestinain relations, I sought to take Mr. Mandela into the “Jewish mind set” and provide insights about the audience he was to address.

Mr. Mandela was as keen listener as he was a speaker, and showed genuine interest in an even exchange. To my mind, this open give-and-take was a measure of the exceptional qualities that distinguished Nelson Mandela. So was the letter of February 16th, 2000 that he addressed to me personally in which he apologized for having to reschedule one of our meetings. He explained that this was due to his need “to extend my stay in Arusha (Tanzania) with a few days since we are hoping to reach a breakthrough in the Burundi Peace Process”. (Between 1993-1999 a bitter and violent civil between the Hutus and Tutsis was raging in Burundi where 300,000 were killed. In December 1999, Mr. Mandela became facilitator of the Burundi Peace Process. His efforts led to the signing of the Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement on August 28th, 2000.) He signed the letter, “I thank you for your support and cooperation”. That Nelson Mandela, always in the public spotlight, took the time and had the thoughtfulness to write such a personal letter in the midst of his public responsibilities and numerous challenges further reinforced the magnitude of his incredible stature.

Mr. Mandela finally met with over 200 representatives of the Jewish community. His sympathetic views on the Palestinians, and in particular his perspective on concessions by Israel to the Palestinians, were not widely accepted by this group (to say the least), but he was undeterred. I feared that he would be entering a lion’s den, but the audience listened and was civil. After his remarks, he graciously opened the floor and an interesting, lively Q & A followed, which Mr. Mandela handled with great skill and patience.

My sense was that Mr. Mandela was not even aware to the extent his ideas were at odds with those of his audience. He was convinced of the vision he wanted to share, his genuine commitment to resolving conflicts was passionate and absolute, and he could claim success as a peacemaker as no other. This was, after all, Nelson Mandela, Madiba, the father of a nation, a true champion of peace and freedom that he brought to his country and craved for people the world over.

Harriet Mandel

New York City, December, 2013

- No Comments

January 2, 2014 by Karen Skinazi

Do What I Do, Not What I Say

My mother says a lot of things that drive me crazy. A favorite, which she has said to me my whole life (and which I try desperately not to say to my own kids) is: “What’s wrong with you??” (variation: “I don’t know what’s wrong with you.”). Another is: “Sarcasm is the lowest form of humor” (even when I’m barely being sarcastic). But there is one thing she says that bothers me like nothing else: “Oh, her? She doesn’t have to work.”

As in, “Did I tell you? So-and-so’s daughter’s husband is making so much money as a radiologist/dermatologist/cardiologist/endodontist. They just bought a huge house in Thornhill Woods. And they have a live-in nanny, and they just spent two weeks at an all-inclusive in Aruba.”

- 1 Comment

December 30, 2013 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Women and Mobsters in the Jazz Age

Chicago and the jazz age have always fascinated Renee Rosen so it seemed almost preordained that she would set her first novel, Dollface, in that particular milieu. A former advertising copywriter with a serious yen for fiction, Rosen let her invented characters rub shoulders with real ones like Al Capone and Hymie Weiss—who, by the way, was not Jewish. But she talks to Lilith’s fiction editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about mobsters who were Jewish—and about the women who loved them.

Chicago and the jazz age have always fascinated Renee Rosen so it seemed almost preordained that she would set her first novel, Dollface, in that particular milieu. A former advertising copywriter with a serious yen for fiction, Rosen let her invented characters rub shoulders with real ones like Al Capone and Hymie Weiss—who, by the way, was not Jewish. But she talks to Lilith’s fiction editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about mobsters who were Jewish—and about the women who loved them.

YZM: How did you make the leap from advertising copywriter to novelist?

RR: I was actually writing fiction before I got into advertising, so for me it was more about pretending to care about my work as a copywriter when my heart was so clearly vested in my own writing. I remember I would get up at 4 a.m. and write until about 8 a.m. when it was time to get ready to go into the office. I’d get home and try to put in another couple of hours in the evening. There were many a days when I wrote though my lunch hour, jotted down notes on my legal pad during meetings and my weekends and days off were always devoted to writing.

YZM: Can you describe your research process for Dollface?

RR: I started with the basics and spent many hours at the Harold Washington Library poring over actual newspaper clips from historical events in the 1920s. Because I live here in Chicago, I was also able to visit the actual landmarks where these events took place. So I’ve been to the site of the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre and I’ve seen the bullet hole in Holy Name Cathedral, etc. Once I had a real feel for the lay of the land, I started looking for people to interview who had ties to 1920s gangsters. That resulted in meeting with a man whose father had been a bookie for Al Capone which was fascinating. I also had lunch with Al Capone’s great niece. There were other people I spoke to as well and some who developed “Chicago Amnesia” and refused to talk to me, which I also found very interesting. To think that some 70 or 80 years later, they were still standing by their oath of silence. The mob runs deep!

- No Comments

December 6, 2013 by Guest Blogger

Orthodox Judaism and the F Word

by Jina Davidovich

I was educated to believe that “Feminism” was the F word. I was raised to think that, while women should excel in the classroom and the boardroom, they should ultimately succumb to their inextricably feminine natures and center their lives on the home. At a young age it seemed that even the rich textual tradition at the heart of Jewish practice vindicated these ideas: Eve sought knowledge and was punished with pain, Tamar was forced to seduce her father-in-law, Judah, to pursue justice, and for centuries women were prohibited from assuming any leadership positions within the Jewish community. To be honest, a structure which did not permit women to achieve success – professional, personal, and spiritual – on the same level as their male counterparts never sat well with me. Despite my deep commitment to the Orthodox Jewish community, feminism was never the “f word” for me – it connoted a different f-word: freedom. Feminism is a philosophy that raised me up and made me a human, rather than just a future wife or mother.

- 2 Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...