by Elizabeth Mandel

King & Mandela

The arrival of Martin Luther King Day six weeks after the death of Nelson Mandela naturally invites discussion of equity and equality. At home, with our daughters, we are reinforcing the lessons Dr. King and Mr. Mandela taught the world. In addition to our family discussions, our daughters are fortunate to have a grandmother who met with Mr. Mandela personally. I look forward, as the girls grow older, to them discussing that experience in depth with my mother, Harriet Mandel.

In the meantime, in memory of Mr. Mandela and in honor of MLK Day, I share below my mother’s memories of those meetings:

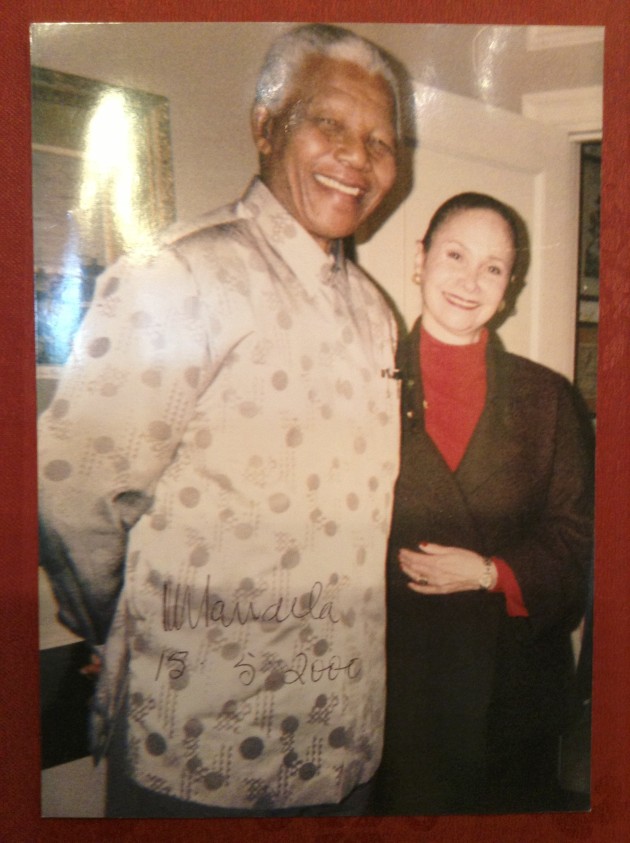

Harriet Mandel and Mr. Mandela

With his dazzling smile and twinkling eyes, radiating warmth, charm, and charisma and dressed in a signature boldly patterned shirt, Nelson Mandela strode into the room for our meeting. It has been 13 years since I had the uncommon privilege of engaging in extended conversations with Mr. Mandela, but the memories remain powerful as ever.

Nelson Mandela’s story made my spirits soar as he led South Africa in its dramatic journey from apartheid to democracy. Along with the rest of the world, I tracked this life lived on the highest planes of human fortitude, endurance and purpose. We longed for the release of this indomitable spirit from prison, and were exhilarated by his example in freedom. Imagine how I felt when an opportunity came for me to meet this luminous hero.

In the year 2000, South African Ambassador to the United States Sheila Sisulu introduced me to Nelson Mandela. Through my career in international diplomacy and Jewish community relations, I had come to know Mrs. Sisulu when she served as South Africa’s Consul General in NYC from 1997-1999. We were guests in each other’s homes (I had the honor of hosting her in ours for Shabbat dinner) and our professional relationship developed into a personal friendship. Mrs. Sisulu was a lifelong activist for educating and empowering the underprivileged, and a civil rights supporter who fought against apartheid. She was also the daughter-in-law of Walter Sisulu who, together with Mr. Mandela, founded the African National Congress’ (ANC) military wing, and served at the same time as Mr. Mandela in Robben Island prison. In 1999, she was personally appointed by Mr. Mandela as the first black person and first woman to represent South Africa as the country’s ambassador to the United States.

In 2000, Mr. Mandela was in the process of establishing the Nelson Mandela Foundation, with the mission of promoting dialogue to resolve global conflicts. He was deeply invested in exploring a resolution to the Arab-Israeli conflict, and planned to come to New York City to speak with “New York Jewry” to garner support for his Middle East peace plan. Mrs. Sisulu asked me to arrange for a meeting between Mr. Mandela and Jewish community members. She also asked that, given the controversial nature of the subject, Mr. Mandela and I meet first for preparatory discussions.

This came against the background of complicated relationships between Mr. Mandela, Israel and the Palestinians. Israel maintained close military ties with apartheid South Africa until the end of the regime. Mr. Mandela, long associated with national liberation causes, was supportive of the Palestinians, and critical of Israeli policy towards them, though he did publicly support Israel’s right to exist. Neither Israel nor the Palestinians gave much support to his plan (which each thought was either to simplistic or too excessive), but Mr. Mandela was determined to make his case, and forged on.

In the first half of 2000, Mrs. Sisulu arranged two extended one-on-one conversations between Mr. Mandela and me, both times in his suite at the Waldorf Astoria. I vividly remember Mr. Mandela walking into the room for the first time. My immediate thought was, here is a prince – which indeed he was. I later learned that he was the son of Chief Henry Mandela of the Madiba clan of the Xhosa-speaking Tembu people. He had relinquished his claim to the chieftainship to become a lawyer. He radiated grace, dignity and energy, yet was surprisingly down to earth. He unhesitatingly embraced me in a warm, welcoming hug and joked that Mandela and Mandel were destined to meet.

It was a rare honor to spend hours talking with this noble man, but it also felt relaxed and comfortable. In fact, it was truly remarkable, and a testament to the greatness of this global hero, that he put me so at ease and that our conversation flowed as if we were long time friends. Mr. Mandela’s charisma was exhilarating, but it was his obvious respect and consideration for the opinions of others – in this case, a stranger’s – that left a lasting impression and underscored his distinctiveness.

We spoke casually for a while, and then turned to the purpose of the meeting. Mr. Mandela noted that he was aware that his sympathetic views towards the Palestinians would probably not find a welcome audience in the Jewish community. However, he wanted to engage this group because he believed that the American Jewish community’s understanding of his peace mission would promote his cause in Israel. He asked that I give him background on and insight into the American Jewish community to help him communicate in resonant ways.

My background is in international affairs, with a specialization in the Middle East, and I had spent my professional life dealing with global leaders on this issue.. But Nelson Mandela was in a league of his own, and I was humbled by my challenge. Rather than express my personal opinion on the complex issue of Israeli-Palestinain relations, I sought to take Mr. Mandela into the “Jewish mind set” and provide insights about the audience he was to address.

Mr. Mandela was as keen listener as he was a speaker, and showed genuine interest in an even exchange. To my mind, this open give-and-take was a measure of the exceptional qualities that distinguished Nelson Mandela. So was the letter of February 16th, 2000 that he addressed to me personally in which he apologized for having to reschedule one of our meetings. He explained that this was due to his need “to extend my stay in Arusha (Tanzania) with a few days since we are hoping to reach a breakthrough in the Burundi Peace Process”. (Between 1993-1999 a bitter and violent civil between the Hutus and Tutsis was raging in Burundi where 300,000 were killed. In December 1999, Mr. Mandela became facilitator of the Burundi Peace Process. His efforts led to the signing of the Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement on August 28th, 2000.) He signed the letter, “I thank you for your support and cooperation”. That Nelson Mandela, always in the public spotlight, took the time and had the thoughtfulness to write such a personal letter in the midst of his public responsibilities and numerous challenges further reinforced the magnitude of his incredible stature.

Mr. Mandela finally met with over 200 representatives of the Jewish community. His sympathetic views on the Palestinians, and in particular his perspective on concessions by Israel to the Palestinians, were not widely accepted by this group (to say the least), but he was undeterred. I feared that he would be entering a lion’s den, but the audience listened and was civil. After his remarks, he graciously opened the floor and an interesting, lively Q & A followed, which Mr. Mandela handled with great skill and patience.

My sense was that Mr. Mandela was not even aware to the extent his ideas were at odds with those of his audience. He was convinced of the vision he wanted to share, his genuine commitment to resolving conflicts was passionate and absolute, and he could claim success as a peacemaker as no other. This was, after all, Nelson Mandela, Madiba, the father of a nation, a true champion of peace and freedom that he brought to his country and craved for people the world over.

Harriet Mandel

New York City, December, 2013