August 20, 2013 by Elana Sztokman

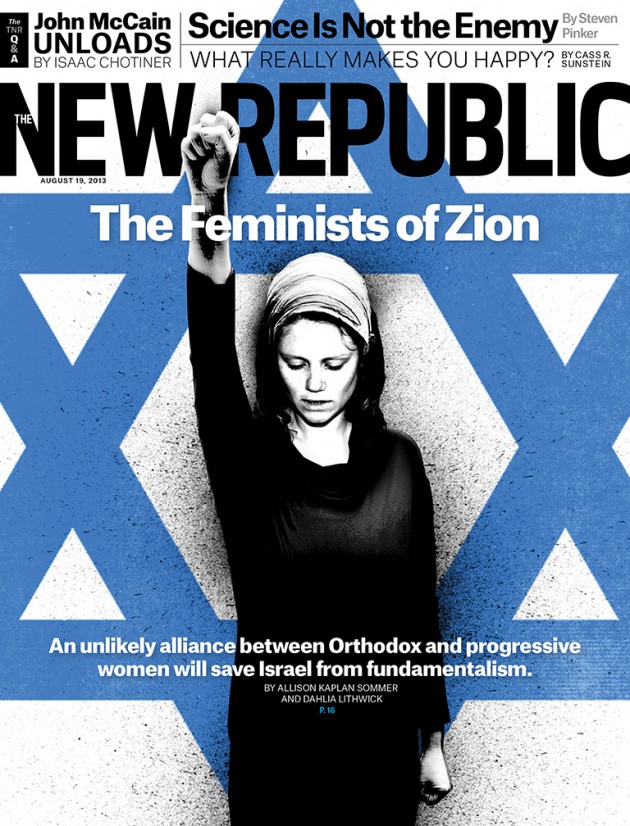

Not Your Typical Story, Not Your Typical Cover Girl

It’s a thrill to see an image of yourself on the cover on New Republic. Well, it wasn’t literally me on the front cover, but it was an image of Orthodox Jewish women with a headline about Orthodox Jewish women, so it might as well have been. For Orthodox women, to see a story like this kind of feels like someone walked into your home and wrote a story about your life. Like I said, a little thrill.

Of course, last week’s story by Allison Kaplan Sommer and Dahlia Lithwick wasn’t a typical story about Orthodox women, not the Faye Kellerman type of soft, gentle, glowing obedience to a set of rules that glorify traditional gender roles and female body cover. This wasn’t Aish or Chabad or even Oprah sharing an idealized puff-piece about “The Jewish Woman” and how peace in the world rests on her divine, passive femininity. This was a very different narrative. It was about women who are definitely not content and satisfied with social demands placed squarely upon them. It was about Orthodox women fighting for change. Maybe that’s why I liked it so much.

The story of encroaching demands on women’s bodies – cover up more, be more silent, stay off the street, go to the back of the bus, don’t let anyone see your face or hear your voice — began decades ago but has been increasingly escalating. Today, demands placed on women are at times accompanied by violence, whether it’s chairs being thrown at the Western Wall or rocks being thrown in Beit Shemesh at women walking on a street where women are banned, or wearing a skirt that shows too much of her calf. This is a story about radical ideas and radical forces taking over religious Judaism while the secular world has remained largely indifferent.

This religious radicalism rests on an ancient misogyny, the idea that if women’s bodies and lives are controlled by the men in the world, all will be good in the universe. I think of it as the Ahashverosh model. We read this idea in the Book of Esther. When King Ahashverosh wanted to show off his power, he summoned his wife Vashti to “appear”, because we all know that having a gorgeous wife makes you powerful (heck, maybe I should get one, too). And when Vashti refused (you go girl!), well, the king was worried that all hell would break loose. So not only did he dethrone her and reportedly have her killed, but most importantly, he wrote to his entire kingdom about it. He told his aides: “When the king’s letter shall be published throughout all his kingdom, all the wives will give to their husbands honor, both to great and small…. that every man should bear rule in his own house, and speak according to the language of his people.” Meaning, as long as each man is ruler over his household – read, over his wife – there will be peace in all 127 lands. It’s the unfortunately resilient idea that political order relies on men keeping women in their place.

- 1 Comment

August 14, 2013 by Maya Bernstein

Leaning In Means Letting Go

In her cover story of Lilith’s summer issue, Gabrielle Birkner takes a hard look at the economic challenge facing women who take seriously Sheryl Sandberg’s plea to “lean in” to their careers, even as they begin to have children. She points out that quality day care often costs more than women are earning, and concludes: “Leaning in necessitates not only a “will to lead,” but also a structure that supports women’s ambitions. Access to quality, affordable childcare is key.” In another recent cover story on this topic, Judith Warner, writing for the New York Times magazine, comes to a similar conclusion. She points out that the debate about women in the workplace, with its binary focus on whether or not women should opt to “lean into” work or “lean into” their home lives, is actually misplaced. She writes, “at a time when fewer families than ever can afford to live on less than two full-time salaries, achieving work-life balance may well be less a gender issue than an economic one.”

In her cover story of Lilith’s summer issue, Gabrielle Birkner takes a hard look at the economic challenge facing women who take seriously Sheryl Sandberg’s plea to “lean in” to their careers, even as they begin to have children. She points out that quality day care often costs more than women are earning, and concludes: “Leaning in necessitates not only a “will to lead,” but also a structure that supports women’s ambitions. Access to quality, affordable childcare is key.” In another recent cover story on this topic, Judith Warner, writing for the New York Times magazine, comes to a similar conclusion. She points out that the debate about women in the workplace, with its binary focus on whether or not women should opt to “lean into” work or “lean into” their home lives, is actually misplaced. She writes, “at a time when fewer families than ever can afford to live on less than two full-time salaries, achieving work-life balance may well be less a gender issue than an economic one.”

The “Lean In” debate, with its focus on women and their personal decisions, is masking a broader societal challenge, which is felt to the extreme by families in general, and women in particular. We have not figured out how to ensure that children receive quality care, and the work force quality and committed employees. The lightening rod of this debate has been the working mother, and she has been blamed and shoved from side to side, quite roughly. Warner points out that the pendulum has been swinging wildly, backed up by “scientific studies,” which seem to simply offer support for the latest trend. She implies that the currently popular plea to “lean in” to work life, and to avoid “excessive mothering,” is simply a reaction to the economic climate in which we reside:

The women of the opt-out revolution left the workforce at a time when the prevailing ideas about motherhood idealized full-time, round-the-clock, child-centered devotion. In 2000, for example, with the economy strong…almost 40 percent of respondents to the General Social Survey told researchers they believed a mother’s working was harmful to her children (an increase of eight percentage points since 1994). But by 2010…fully 75 percent of Americans agreed with the statement that “a working mother can establish just as warm and secure a relationship with her children as a mother who does not work.” And after decades of well-publicized academic inquiry into the effects of maternal separation and the dangers of day care, a new generation of social scientists was publishing research on the negative effects of excessive mothering: more depression and worse general health among mothers, according to the American Psychological Association.

- 2 Comments

August 14, 2013 by Guest Blogger

Priced Out of Participation

by Marcia Cohn Spiegel

I just finished reading about the “Lean In” era and remembered that in the summer of 1980 there was a feminist preconference for CAJE (led by Sue Levi Elwell, Paulette Benson and myself). The main concern of the Jewish women educators and professionals who attended was how, on the salary they were paid and the hours that they worked, they could afford child care, religious school, camp and synagogue membership.

I just finished reading about the “Lean In” era and remembered that in the summer of 1980 there was a feminist preconference for CAJE (led by Sue Levi Elwell, Paulette Benson and myself). The main concern of the Jewish women educators and professionals who attended was how, on the salary they were paid and the hours that they worked, they could afford child care, religious school, camp and synagogue membership.

They were concerned that their work as Jewish professionals would not allow them to be part of the organized Jewish community. They were priced out of participation.

So what else is new?

- No Comments

August 13, 2013 by The Editors

Meet Amira Dotan!

Amira Dotan is a former Knesset member and the first woman to attain the rank of brigadier general in the Israeli Defense Forces, where she served from 1965-88. She is the founder and joint CEO of the Mediation Center at Neve Tzedek, serves on corporate boards, and is a trustee of several of Israel’s academic institutions. She is currently involved in fascinating work with various populations in the Negev. General Dotan shares with Susan Weidman Schneider of Lilith and Rabbi Julie Schonfeld of the Conservative Rabbinical Assembly the honor of being named recently as a Thomson Fellow.

Last week, Amira Dotan addressed a breakfast meeting hosted by Lilith and the Rabbinical Assembly to talk about women’s roles in many sectors of Israeli society today.

- No Comments

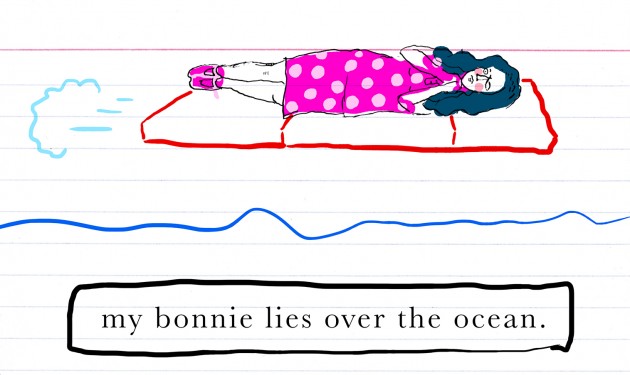

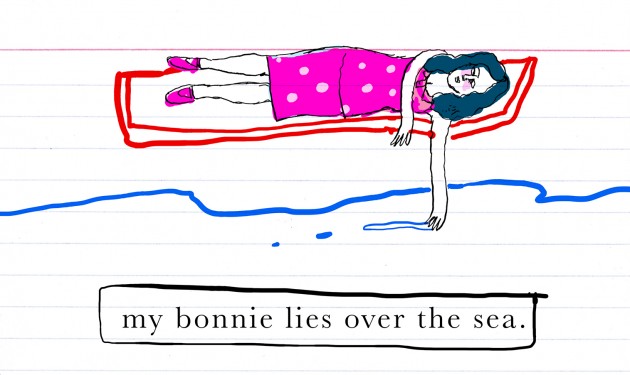

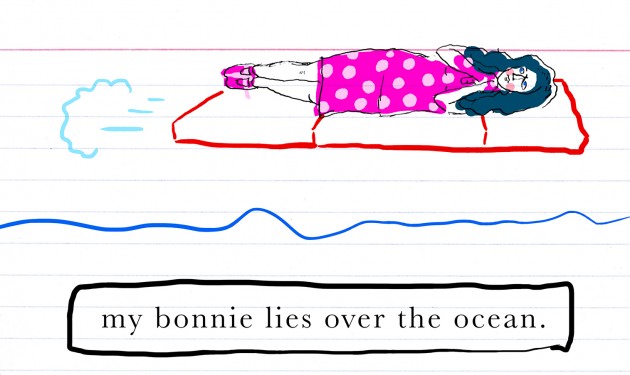

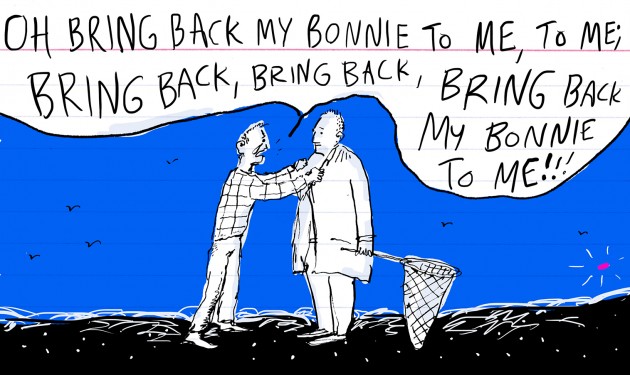

August 8, 2013 by Liana Finck

My Bonnie

Liana Finck received a Fulbright Fellowship and a Six Points Fellowship for Emerging Jewish Artists. She is finishing a graphic novel, forthcoming from Ecco Press, based on the Bintel Brief, a beloved Yiddish advice column that was published in the Forward newspaper beginning in 1906.

- No Comments

August 7, 2013 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Marked Woman

Jews have had a heinous association with tattoos: millions were marked, against their will, as they filed through the gates of concentration camps that dotted Europe like the spores of a horrific and malignant disease. Even after the survivors were liberated, the incised blue numbers remained, silent yet eloquent witnesses to the systematic process of dehumanization of which they were only a part.

Jews have had a heinous association with tattoos: millions were marked, against their will, as they filed through the gates of concentration camps that dotted Europe like the spores of a horrific and malignant disease. Even after the survivors were liberated, the incised blue numbers remained, silent yet eloquent witnesses to the systematic process of dehumanization of which they were only a part.

Fast forward to Margot Mifflin’s recently reissued Bodies of Subversion: A Secret History of Women and Tattoos, a brilliant and compulsively readable volume that offers an alternative range of meanings: tattoo as a symbol of empowerment, of catharsis, or as a way of establishing new boundaries for the female body. And one of the featured subjects, Marina Vainshtein, will no doubt cause to you reexamine any ideas you might have had on the topic of Jews and tattoos.

Vainshtein, who these days goes by the name of Spike, was born in the Soviet Union and came to the United States when she was four. She was raised in California, and in the early 1990s, when she was eighteen, began having explicit Holocaust imagery tattooed on her skin. Now, more than twenty years later, she is covered. Mifflin lists these tattoos in some detail: a smoke-belching crematorium, naked bodies hanging from gallows, an old woman chained to a coffin of nails, an escaped inmate dying on a electrified fence, a can of Zyklon B, (used in gas chambers), a skeleton in an open casket reading Kaddish, a star of David, and, in Hebrew, the words, Earth hide not my blood (from the book of Job) andNever Forget. Using her body as both her sounding board and her canvas, Vainshtein has totally subverted both the imagery and the process: her tattoos are chosen and worn with pride, not shame, and they delineate aspects of her heritage in a graphic, unmistakable way—she is the granddaughter of survivors. When questioned about her unusual choice, Mifflin quotes Vainshtein as saying, “Why not have external scars to represent the internal scars?” Mifflin posits that even those born long after the Holocaust still suffer psychic damage—and pain. I had a chance to communicate with Vainshtein via e-mail and here is what she shared with me:

My first tattoo was a MAGEN DAVID on the inside of my left arm. After that was a piece called ADAGIO on my right arm. Adagio is a man playing the violin and represents the orchestra that was placed at the gates of Auschwitz to fool the herd of incoming prisoners into thinking that it was a resort rather than a death camp.

At this point almost 90% of my body is covered in holocaust memorial tattoos; this includes a portrait of my grandparents who survived the pogroms in the Ukraine.

Reaction to my work has spanned the gamut from complimentary/fascination to utter disgust. But what I’ve done over the 22 years has mainly been a tool to educate and shed light on a horrific time in history. Many kids barely skim over WWII these days and some have no idea of the atrocities that occurred. And even still history repeats itself and the barbaric treatment of people continues, i.e. the Armenian holocaust, Sierra Leone, ethnic cleansing in Bosnia, Serbia, Africa etc.

All the artists who have worked on me (12 in total) have either been my friends or have become friends.

Yona Zeldis McDonough is Lilith’s fiction editor.

- No Comments

August 5, 2013 by Liz Lawler

Women, Work, and Monetizing Misfortune

Parenthood is like a tattoo, you don’t quite realize the unyielding permanence of the thing until it’s too late to turn back. This constancy yields endless opportunities for guilt and self-doubt. Decisions about childcare, for instance, are a major source of angst. Gabrielle Birkner’s recent article in this magazine brought some up for me. Thinking about nannies, daycare, and money summons feelings and knee-jerk opinions that I’m often loath to share in public. But here goes.

There are many angles from which to consider the question of childcare. Birkner discusses multiple family structures: single, married, single-income, dual income, etc. I come from the dual parent, 1.5 income category. I generate income, but really just enough to cover my tracks, shopping-wise. So why did I “choose” to limit my career to part-time and free-lance? Above all, I am home with my kids because I want to be. Because I believe that I am the best qualified to tend to their needs, and my husband makes enough to support us (that last bit is key, I know). We also did the math and realized that indeed, we would pay more in childcare than I made in my full time job. So the finances were simple enough. But certainly, for a single parent, the need for income and subsequently childcare compels you in the other direction. So your options become: nanny, secular day-care (or “early-learning center”) or now religious day-care, thanks to the growing number of religious institutions getting in on the act.

- No Comments

July 31, 2013 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Two of a Kind

In her fifth novel, Two of a Kind, Lilith’s Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough tackles the still-thorny subject of intermarriage. Christina Connelly, Catholic by birth, falls in love with Dr. Andy Stern, who is Jewish. Among the many impediments to their ultimate happiness is Andy’s mother, Ida, a Holocaust survivor. Below is an excerpt:

The streets of this unfamiliar neighborhood on the warm, late spring were lovely: brownstone and limestone houses side by side, mature trees, flowers in urns, window boxes and planters. In another mood, Ida would have stopped to linger but today she had a mission. An urgent mission. It was the unborn baby. The baby that belonged to her son and that this Christina person might actually abort. For Ida, the loss of this baby would be a fresh sorrow heaped upon so many past sorrows. She didn’t think her old heart could stand it.

There had been another lost baby, decades ago, fathered by Jurgi, the boy who lived across the road. He’d been her best friend for years, like a brother, until they’d been hurriedly married and practically shoved into a room alone together after the wedding. “Do you know what we’re supposed to do?” he had whispered, suspecting, correctly as it turned out, that their parents were listening anxiously at the door.

“Not really,” she had answered, knowing she should be more nervous than she was, but this was Jurgi and how could she be nervous with Jurgi? They did not figure out what they were supposed to do that night, or the night after that. But on the third night, he came into the room at Ida’s house that they were now told was theirs looking very serious. “I understand now,” he said to her. “My father explained it all to me.”

- No Comments

July 31, 2013 by Susan Weidman Schneider

How do we measure change?

Read Susan Weidman Schneider’s editorial, and so much more, in Lilith’s summer 2013 issue!

Read Susan Weidman Schneider’s editorial, and so much more, in Lilith’s summer 2013 issue!

Maybe you smoked cigarettes a long time ago. Now? Not so likely. Smoking looks retrograde even in an anachronistic setting like TV’s Mad Men. As the smoking seems retro, so too do the sexist attitudes and sexual harassment of that earlier era. Attitudes change, laws then follow suit. (No smoking in theaters or planes, in restaurants or in many public parks.)

And the Supreme Court of the United States has recognized gay marriage, overturning unjust laws that violated the civil rights of same-sex spouses. The rapid change in attitudes about LGBT issues has been remarkable. From the overt opprobrium during the 1980s AIDS epidemic to social and legal acceptance today? Less than 30 years, and a sea change.

Let’s hope that very soon the attitudes toward women in Jewish divorce law will seem at least as retro as smoking, and that legal succor will follow. As with marriage equality in secular law, attitudes have to shift for new interpretations of Jewish law to take hold. June 2013 was quite a month for attempting such change: women by the hundreds wore tallitot and prayed out loud at the Western Wall in Jerusalem; a “summit” discussed radical ways of countering divorce injustice; and whole new category of Jewish female clergy emerged.

So why can’t we cheer for these successes, however modest they may seem to some? Perhaps because we’re a little skeptical. In the wake of an Agunah Summit in late June, we’ve done an in-office retrospective on our previous articles about Jewish women “chained” in their marriages. Under Jewish law, only the husband can instigate divorce proceedings. From this inequity springs the fact that many husbands extort money or child-custody concessions from their wives in exchange for authorizing the divorce. Blu Greenberg, a prime mover behind the summit and a Lilith contributing editor, first wrote about this subject for the magazine in 1976! (Track this coverage at Lilith.org, part of the stunning archive of back issues fully searchable at our new website.) Blu’s oft-cited statement on how to change Jewish law: “Where there’s a rabbinic will, there’s a halakhic way.” Yet four decades of activism have until now yielded little to free a woman powerless to extricate herself from a bad marriage.

- No Comments

July 26, 2013 by Ester Bloom

Here On Purpose

My Fiction teacher and my Non-Fiction teacher are smart, funny, dark-haired Jews from Brooklyn, and here we are together halfway around the world in Vilnius, Lithuania, studying writing via SLS (Summer Literary Seminars). The bosomy, intellectual Litvak is our common ancestor, and she decamped for good reason—pogroms, pine forests, maybe the weather; after all, where else do you need to buy a fuchsia raincoat in late July? If this is mid-summer, I’d hate to meet March, but I smile because the buildings, especially in Old Town, are the color of morning light and fringed with flowers, because the stone streets roam like teenagers, no plan, twisting here on impulse and turning there, until they arrive somewhere, or don’t.

A particular sign on a particular building on a particular street I find sometimes reads INTEGRITY. Fifty years ago, even twenty-five, this city spoke Russian. Now, when I walk into a restaurant, a woman who would be a model anywhere else but who is average here greets me “Hello” and hands me a menu that knows words like “sandwich” and “vegetarian.”

Everyone from the older generation is furious, the way we would be if our kids all took up Mandarin without teaching it to us, the way the French were when “lingua franca” stopped meaning “French.” A stout older lady yells at me for a long time when I don’t understand her. It seems to make her happy so I let her, and she lets me buy my Coca-Cola Light, which seems like a fair trade, and I say, “Spasibo” quietly so that she doesn’t need to be appeased and stop yelling if she doesn’t want to.

My husband Ben speaks Russian—he’s here, taking care of the baby while I’m in class—so he soothes bus drivers and kiosk operators and street vendors. Neither of us speaks Lithuanian. We both say “Achoo” a lot, which means “Thanks.” When one of us sneezes, the other says, “You’re welcome.”

A Turkish restaurant advertises falafel. Four glistening greenish patties appear on a plate with Special Sauce. “Achoo?” I say. Skepticism evolves into resignation—they aren’t bad, they’re simply wrong. The waitress asks me what falafel is supposed to be. “Chickpea,” I say. She shakes her head. “Hummus?” I ask. No. Two El-Al pilots cross their legs and look out at the street, amused. I shrug. “Chickpea,” I say again, out of ideas. “Okay,” she says. “I will tell the cook.”

As I leave, the pilots ask me, “Why are you here?”

“To write,” I say.

“So you are here on purpose?”

They are bemused, on a layover; they had never heard of Lithuania before landing. The local parents Ben and I meet in the playground—once the ghetto—are just as bemused: we are visiting Vilnius for two weeks? Why? I refrain from pointing out that they live here. They have a daughter the age of our daughter; they want to take her with them across Route 66. Her name means Sun, a daily plea to the censorious Soviet clouds.

Our daughter’s name means Cheerful. She will eat anything except baby food. When we order herring, she fights us until we give her access to the plate and she throws herself at it like a shark, smiling through brine. She will not remember Lithuania except perhaps her growing body will, that carnivore that only moves forward.

Ester Bloom’s writing has appeared in Slate, Salon, Bite: An Anthology of Flash Fiction, Creative Non-Fiction, the Hairpin, the Awl, the Morning News, Nerve, PANK, Bluestem, Phoebe, Zone 3, and numerous other venues. She blogs on culture for the Huffington Post and is a columnist for Trachodon Magazine and the Billfold.

- 1 Comment

Please wait...

Please wait...