The Lilith Blog 1 of 2

August 20, 2013 by Elana Sztokman

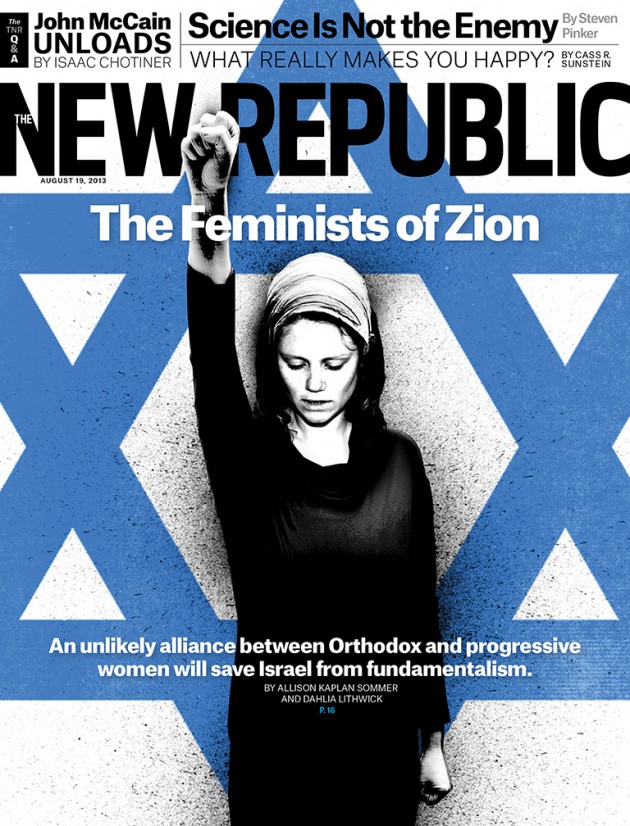

Not Your Typical Story, Not Your Typical Cover Girl

It’s a thrill to see an image of yourself on the cover on New Republic. Well, it wasn’t literally me on the front cover, but it was an image of Orthodox Jewish women with a headline about Orthodox Jewish women, so it might as well have been. For Orthodox women, to see a story like this kind of feels like someone walked into your home and wrote a story about your life. Like I said, a little thrill.

Of course, last week’s story by Allison Kaplan Sommer and Dahlia Lithwick wasn’t a typical story about Orthodox women, not the Faye Kellerman type of soft, gentle, glowing obedience to a set of rules that glorify traditional gender roles and female body cover. This wasn’t Aish or Chabad or even Oprah sharing an idealized puff-piece about “The Jewish Woman” and how peace in the world rests on her divine, passive femininity. This was a very different narrative. It was about women who are definitely not content and satisfied with social demands placed squarely upon them. It was about Orthodox women fighting for change. Maybe that’s why I liked it so much.

The story of encroaching demands on women’s bodies – cover up more, be more silent, stay off the street, go to the back of the bus, don’t let anyone see your face or hear your voice — began decades ago but has been increasingly escalating. Today, demands placed on women are at times accompanied by violence, whether it’s chairs being thrown at the Western Wall or rocks being thrown in Beit Shemesh at women walking on a street where women are banned, or wearing a skirt that shows too much of her calf. This is a story about radical ideas and radical forces taking over religious Judaism while the secular world has remained largely indifferent.

This religious radicalism rests on an ancient misogyny, the idea that if women’s bodies and lives are controlled by the men in the world, all will be good in the universe. I think of it as the Ahashverosh model. We read this idea in the Book of Esther. When King Ahashverosh wanted to show off his power, he summoned his wife Vashti to “appear”, because we all know that having a gorgeous wife makes you powerful (heck, maybe I should get one, too). And when Vashti refused (you go girl!), well, the king was worried that all hell would break loose. So not only did he dethrone her and reportedly have her killed, but most importantly, he wrote to his entire kingdom about it. He told his aides: “When the king’s letter shall be published throughout all his kingdom, all the wives will give to their husbands honor, both to great and small…. that every man should bear rule in his own house, and speak according to the language of his people.” Meaning, as long as each man is ruler over his household – read, over his wife – there will be peace in all 127 lands. It’s the unfortunately resilient idea that political order relies on men keeping women in their place.

Indeed, this same 2500-year-old thinking that is behind the 21st century spate of radical religious misogyny spreading around the world. And obviously it’s not just Judaism. In Islam, Malala has taught us all about what’s going on in the Muslim world – in Egypt, Tunisia, and even Europe. In Christianity, the Paul Ryans of the world are spreading some frightening ideas about finding creative new ways to control women’s bodies. This is a world-wide, cross-religious phenomenon in which new invocations of old misogyny are pushing religions towards violent extremism. And Judaism is, unfortunately, no exception.

Although Orthodoxy is getting more extreme throughout the world, in Israel radical religious misogyny is spreading in particularly troubling ways. This has a lot to do with the lack of separation of religion and state in Israel and the fact that religious parties have disproportionate political power and a astonishing control over some of the state apparatus that monitors people’s personal status. But it’s not just that. It also has to do with secular men supporting religious political forces for their own advancement. The reason why, for example, there are no picture of women on buses in Jerusalem has less to do with what ultra-Orthodox Jews actually want and more to do with what secular businessmen controlling the ads think that haredim want. Similarly, in 2011, when then-Knesset speaker MK Ruby Rivlin decided to ban women singers from the Knesset, he did it not because of his own belief system – he is secular – but for his own political needs to appease certain haredi politicians. When the Shas-controlled Kol Berama radio station banned women’s voices from transmission in 2010, it was the secular male business director Shai Ben-Maor, who went to the Knesset to defend this illegal practice by saying, “This is what our listeners want” – even though research conducted among their listeners showed that 40% actually did not want to ban women’s voices and were actually offended by the practice.

So what really causes radical religious misogyny to spread is not ultra-Orthodox demands, but the perceptions of secular (usually male) politicians and businessmen who think that they know what haredim want and appeal to the most radical demands as if that will please the entire haredi population.

And of course the ones to suffer most through all this are the women. It is the women who literally have no voice and no political power – banned from radio stations, political parties, and a seat in the beit midrash. It is the women whose needs, wishes and ideas are completely ignored and lost amid the waves of political forces trying to own them. And it is women who are literally being stoned and stonewalled as they try to express a different vision for life in Israel.

Against this backdrop, the alignment that the authors described between grass-roots religious women’s groups and organizations calling for religious pluralism in Israel is particularly significant. Women’s groups need the support of secular society in order to effectively make change. These women are not just fighting against their own male leaders but also against the quiet secular acquiescence that has accompanied and enabled the rise of religious radicalism. This alignment is crucial in the process of halting the spread of violent religious radicalism.

It is vital for secular and progressive forces to get behind religious feminism. As we can see throughout the world, religious feminism is on the frontlines in the battle to contain religious radicalism. The whole world should be thanking religious feminists, and backing them. The fate of the world literally rests on their success in this struggle.

Dr Elana Maryles Sztokman is the Executive Director of JOFA, the Jewish Orthodox Feminsit Alliance. Her next book, The War on Women in Israel: How Religious Radicalism is Stifling the Voice of a Nation, is due to be published in February by Soucebooks.

Please wait...

Please wait...