September 9, 2013 by Katie Halper

The Feminism of Camp Kinderland

Though I didn’t know the words feminism or cultural studies or film theory, I was moonlighting as a feminist film critic by the age of five. Preferring musical movies to cartoons, I would point out how films like Grease and Seven Brides for Seven Brothers were “prejudiced against women.” It wasn’t until around age seven that I started using the word sexism, after a babysitter confirmed my belief that Sandy Olsson’s changing for Danny, and not the other way around, was, indeed sexist–as was the whole kidnapping of women scene in Seven Brides. When I saw Pretty Woman, I told my parents that the movie was “feminist. Not activist feminist, but feminist.” To this day, I’m not sure what I meant exactly. But I was onto something, I’m sure.

Believe it or not, neither calling out sexism nor being obsessed with musicals made me very popular at my school. In middle school, my classmates would mock my vigilance, saying “Katie, look at the chalk board! It’s sexist, right?” Or “That volleyball is so sexist, right Katie?”

Luckily, I had a place where my feminism was embraced and not rejected: my summer camp. Founded in 1923 by Jewish communist and socialist workers, most of whom were Yiddish-speaking immigrants, Camp Kinderland was a second home to me, as it had been to my mother and my grandmother. Over the years, its politics have gotten it into trouble. It was almost shut down during the McCarthy era, and more recently it was attacked by the right wing, including Rush Limbaugh, when it was discovered that an Obama nominee had sent her children to this “extremist,” “left wing, Jewish summer camp.” The camp’s commitment to equality for women was a part of its larger commitment to equality for all, justice and fairness. Its rejection of sexism went hand in hand with its rejection of all oppressions and prejudices, whether they were based on gender, sexual orientation, race or class.

- 1 Comment

September 3, 2013 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

In the Courtyard of the Kabbalist

Born in Nashville, TN and raised in Virginia, Ruchama King Feuerman bought herself a one-way ticket to Jerusalem when she was seventeen to study Kabbalah with mystics. She went to college in Israel and returned to the United States to get her MFA at Brooklyn College. The stories she wrote there became Seven Blessings, her acclaimed first novel about matchmaking from St. Martin’s Press; Kirkus Reviews called her, “The Jewish Jane Austen.” Today she lives in New Jersey with her husband and children where, among other things, she runs writing workshops for Orthodox and Hassidic women; she talked to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about the lure of the Talmud, the people she met in Israel and her abiding belief in the power of the story.

Yona Zeldis McDonough: Tell me about the time you spent in Jerusalem.

Ruchama King Feuerman: The ten years I lived in Israel – nine of them in Jerusalem – I fell in love with Torah study. Chumash, midrash, philosophy, Maimonides, law, the works. I loved the act of throwing myself at the text, beating my brains to figure out what Jewish thinkers had thought centuries ago, touching their minds. This was in the eighties when a whole revolution was taking place in Orthodox women’s Torah study. I tutored and taught at Brovender’s, perhaps the first school to teach women Gemara. After six or seven years, though, I started to feel like a walking brain. I found myself craving a more Hassidic type of learning. I met kabbalists, I prayed with the Hassidim, and I studied the Hassidus of Breslev, Chabad, Chernobyl, whatever I stumbled upon. I loved how if there was a great rabbi or rebbetzin you wanted to talk to, you could just get on a bus and go meet them. I loved the many wise and powerful Jewish women I met there with their artistic head scarves. Jerusalem seems to breed them. Three decades later, I can’t stop writing about Jerusalem, the personalities I met there.

- No Comments

September 1, 2013 by Tamar Prager

Two Mothers Taking Both Roads

The day I gave birth to our son my desire for a doctorate vanished. The urge to be with Hanan trumped everyone and everything. In the first six months, I stayed home with Hanan full time, his caretaker from morning till night and loved it. I had purpose and a love so deep it fueled me through a year of sleep deprivation.

A few years before Hanan was born I changed careers. Towards the end of my schooling I became pregnant and took my boards one week before delivery. The timing was perfect. I got licensed, gave birth, and had the luxury of full time motherhood with no pressure from a job awaiting my return. But while immersed in the hazy, dream-like state of infant care, I had thoughts of launching my career as an adult nurse practitioner. What was the point of my training I thought, if I never practiced? If I waited too long, I would be a stale candidate, not as likely to get hired. But motherhood seemed to be the greatest position I could ever assume, so I pushed off these nagging thoughts and sunk deeply into its embrace. My days began with nursing and ended with nursing. My identity as mother centered me more than anything else ever had and I was grateful for the opportunity to be close to my child.

Every woman has her opinion about how the mother-baby dyad ought to be. And typically these opinions are framed with the assumption that there is but one mother who must choose between child and career. But my son has two mothers who have chosen both roads. For me and my wife, the dynamics between career, childcare, and motherhood turn on a different axis. The questions that arise for us are centered around the definition of motherhood and the ways that each of us can claim our own unique role as Hanan’s mother. When I chose to start working outside of the home, I left Hanan in the arms of his Ema. My own personal convictions were strongly in favor of caring for our son on our own. I had the support of my wife who would have to restructure her career obligations in order to make our scenario doable. As long as Hanan was being cared for by one of us I felt free to give of myself outside the home. So at six months, I began working as a nurse practitioner in a practice ten blocks away; on lunch breaks I met my wife and son on the periphery of Central Park and quickly switched roles, latching him to my breast. It was not an easy transition physically or emotionally but each of my roles demanded that I move swiftly between them. Financially we were able to afford two part time jobs that allowed both of us to be with him on a rotating schedule. While I was working, my wife cared for Hanan. On her days at the office, I took over childcare. At seventeen months postpartum, the arrangement has kept up, tiring to the bone and yet a gift.

When I’m at work I give patients my all. I return phone calls at night, write lab letters on the weekends, and read up on diagnoses and treatment protocol to stay informed. I am fully committed to my job while wanting to be more committed at home. I don’t feel I can have it all because there is no such thing. I am learning to accept this, but the nature of giving to two separate spheres makes me frustrated and annoyed at times. Many, many hours have been spent, wishing I did not have to focus on my job obligations while my son plays happily on our living room floor. He is happy to have my unbroken engagement, but also able to play on his own. There have been many moments when I have wanted to return to being a full-time “stay at home mother.” For me, it is the only perfect fit in the world. Being wrapped up in Hanan, in the day-to- day labyrinth of work, play, and sleep gives me the greatest joy and meaning.

And yet, this is simply one approach, one voice in this never-ending conversation. Who am I to judge other women and their choices? There are endless permutations of obligations, preferences, abilities, and finances that shape a family’s decision on childcare. These factors are ours and ours alone. No two women have the same scenario and if they did we would all be less likely to judge our fellow mothers. If you trade in a million dollar paycheck for afternoon walks in the park and playgrounds, or opt for the boardroom instead, I salute you (granted this is a simplified version of a real life calculus). I implore women to find their desire and to go after it. I believe it is a joyous, life affirming lot to be wrapped up in my role as Hanan’s mother, but it is my belief. Mothers ought to listen to their beliefs and desires and do their best to construct a life that provides meaning and happiness.

Read more on Motherhood in the “Lean-In” Era here.

photo credit: Geoffery Kehrig via photopin cc

- No Comments

August 30, 2013 by Ilana Kurshan

The Pinnacle of Israeli Education

I read Gabrielle Birkner’s essay on the high cost of early childcare during our annual August visit from our home in Jerusalem to our extended families’ homes in the New York area. We travel to the States each year in August because this is the one month when we do not have childcare for our toddler son and infant twin girls. Living in Jerusalem, we are fortunate to benefit from the network of excellent Mishpachtonim. This term, from the Hebrew word for family, is a cross between a home daycare and a playgroup. Most of our peers who are working parents of young children place their children in such settings, rather than hiring a private caretaker or sending to an institutionalized preschool. In a Mishpachton the caregiver is generally a young mother who assumes responsibility for several young children during working hours.

I read Gabrielle Birkner’s essay on the high cost of early childcare during our annual August visit from our home in Jerusalem to our extended families’ homes in the New York area. We travel to the States each year in August because this is the one month when we do not have childcare for our toddler son and infant twin girls. Living in Jerusalem, we are fortunate to benefit from the network of excellent Mishpachtonim. This term, from the Hebrew word for family, is a cross between a home daycare and a playgroup. Most of our peers who are working parents of young children place their children in such settings, rather than hiring a private caretaker or sending to an institutionalized preschool. In a Mishpachton the caregiver is generally a young mother who assumes responsibility for several young children during working hours.

- No Comments

August 29, 2013 by Sarah M. Seltzer

Orange is Our New Obsession

Summer 2013: the season that those of us blessed with Netflix accounts compulsively binge-watched the women’s prison dramedy, “Orange is the New Black.” The series follows a WASPy Smithie named Piper Chapman (the fictional avatar of memoirist Piper Kerman) during her year in the Fed for a youthful indiscretion: acting as a drug mule for her ex-girlfriend. In each episode, viewers not only encounter the sexually flexible love triangles, beefs, and tribulations of the inmates, but also heartbreaking flashbacks that show how they ended up behind bars.

Summer 2013: the season that those of us blessed with Netflix accounts compulsively binge-watched the women’s prison dramedy, “Orange is the New Black.” The series follows a WASPy Smithie named Piper Chapman (the fictional avatar of memoirist Piper Kerman) during her year in the Fed for a youthful indiscretion: acting as a drug mule for her ex-girlfriend. In each episode, viewers not only encounter the sexually flexible love triangles, beefs, and tribulations of the inmates, but also heartbreaking flashbacks that show how they ended up behind bars.

My experience as a viewer was typically intense. I suffered acute insomnia from hours of overstimulation as my husband and I raced towards the final episode. I lay in bed pondering the characters’ fates (“They’re not real!” I reminded myself). I openly sobbed on my couch as the plotlines deepened, exploding the broader caricatures we had initially seen. One supposedly brash inmate, Taystee, returns to prison after struggling on the outside; another stoic inmate, Ms. Claudette, who had finally learned to hope for release, loses that hope. And the kicker: the unstable but observant Suzanne, who’s called “Crazy Eyes” by the other inmates, poignantly asks Piper to explain why they call her that–indicting the audience for laughing at her in earlier episodes.

After I finished watching the show, my obsessing continued. I followed the debate about the show’s accuracy, its race and gender politics, including its groundbreaking transgender character, Sophia, played by Laverne Cox, a transgender actress. Is it okay to use a morally ambiguous white protagonist as a “Trojan Horse” to illuminate the lives of women of color–as the show’s creator Jenji Kohan asserted she did on NPR’s Fresh Air? (Kohan, who’s Jewish, also noted in the interview, with some glee, that Piper Chapman is a “WASPy, cold shiksa.)

And as Roxane Gay asks, is the show’s glowing reception really earned, or are we so starved for decent content about diverse women, that any such show with reasonable smarts seems more revelatory than it actually is (I call this the “Juno Effect”)?

- No Comments

August 29, 2013 by Chanel Dubofsky

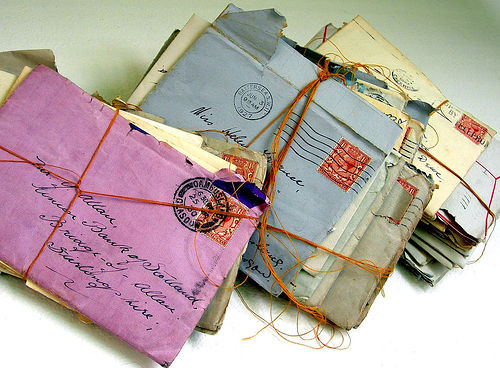

A Blue Slip and a Bag of Letters

There are two new things of relevance. First is a blue slip, belonging to my grandmother, which I unearthed from a bag of other things of hers in a closet. (Also in the bag: letters and cards I sent her, a sweater of hers which used to be mine.) I kept the slip, and threw away everything else. The slip is narrow and stiff, and even though I aspire to be the kind of person who’s daring enough to wear it as a skirt, I never will. It’s strange that I’m keeping it, the memories that it carries are the least pungent.

There are two new things of relevance. First is a blue slip, belonging to my grandmother, which I unearthed from a bag of other things of hers in a closet. (Also in the bag: letters and cards I sent her, a sweater of hers which used to be mine.) I kept the slip, and threw away everything else. The slip is narrow and stiff, and even though I aspire to be the kind of person who’s daring enough to wear it as a skirt, I never will. It’s strange that I’m keeping it, the memories that it carries are the least pungent.

The second thing is a set of wooden bookends in the shape of ducks. Mallards, I think, but really, I don’t know ducks. My uncle sent them to me after I replied yes to his email: “Your aunt and I are doing some cleaning and we found these bookends. I bought them for your mother years ago at Johnson’s Bookstore. Now that you have your own place, would you want them?”

I remember these bookends from our house- heavy, but oddly slippery on the bottom. They probably can’t be trusted to support too many books. They’re kitschy. When I said yes to them, I was thinking about my grandmother telling me that one day, when I had a house, I could put all the antiques she collected and would leave me in it. I couldn’t imagine owning a house and filling it with so many things that were so beautiful and so cumbersome. But these are just bookends.

- 1 Comment

August 28, 2013 by Liana Finck

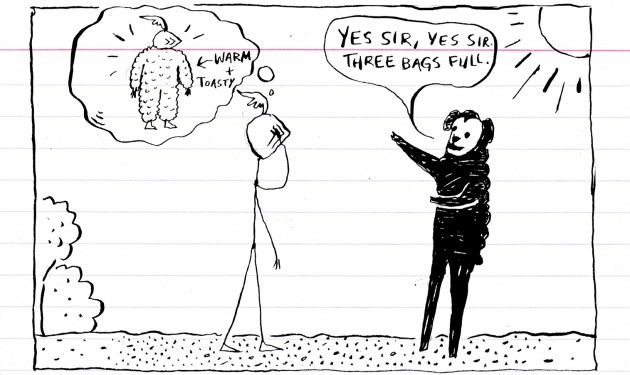

Cold, Cold, Knight

Liana Finck received a Fulbright Fellowship and a Six Points Fellowship for Emerging Jewish Artists. She is finishing a graphic novel, forthcoming from Ecco Press, based on the Bintel Brief, a beloved Yiddish advice column that was published in the Forward newspaper beginning in 1906.

- No Comments

August 27, 2013 by Merissa Nathan Gerson

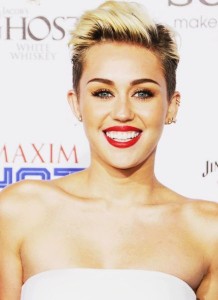

Miley Cyrus and a Whole Lot of Wrong

I have what I am going to term Miley fever. It started when I began watching the VMA replays and there she was, in her horrible glory, an emblem of America’s worst social ills. Then, what followed, an obsessive reading and re-reading of the articles meant to illuminate what we had just witnessed. And one by one I realized the writers were themselves exhibiting subtle sexism and racism of their own. Is Miley the social ill, or is she the catalyst to revealing our deepest issues?

I have what I am going to term Miley fever. It started when I began watching the VMA replays and there she was, in her horrible glory, an emblem of America’s worst social ills. Then, what followed, an obsessive reading and re-reading of the articles meant to illuminate what we had just witnessed. And one by one I realized the writers were themselves exhibiting subtle sexism and racism of their own. Is Miley the social ill, or is she the catalyst to revealing our deepest issues?

It wasn’t just the sideways tongue, or the bad costumes, or the wannabe Katy Perry set. It wasn’t the poor allusions to Britney, or the fact that there was little to no actual dancing happening on that stage. It was the basic fact that first and foremost, not even naked and alone, not even on the most intimate of beds would anyone want to see or experience those lewd moves. They weren’t sexy, they weren’t strip club worthy, they weren’t elegant, they weren’t really anything. There was a kid on stage with a lot of stuffed animals dressed as black women, or black women dressed as stuffed animals, and she was acting out everything she learned and didn’t learn on TV.

- 2 Comments

August 27, 2013 by Ester Bloom

Finding Jesus in England

photo by author

If Jesus really had come back, wouldn’t he stay a while? Set up a carpentry shop somewhere in Bethlehem and live quietly there, making pita and salad in his flat, showing the wounds in his hands to the little ones who crowd his door, and turning water to wine to serve the drop-in guests who have one quick question about Paradise?

My husband, my 11-month-old, and I are standing before a Christian children’s souvenir store called “Shalom: The Rainbow Shop,” in the village of Bourton-on-the-Water. The baby is making noises like a raptor and eating her hat. We recently arrived in the British countryside from Vilnius, Lithuania, and are still adjusting to the transition from East to West. Kipling, that most English of poets, wrote, “East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet.” What would he make of this mash-up of religions, a display with the same blue-

- No Comments

August 23, 2013 by Melissa Tapper Goldman

On the Jewishness of Minding Your Own Damn Business

Tony Fischer Photography

It’s been a banner month for sexting and moralizing about sexting. I offer no conclusions about Anthony Weiner’s most recent spate of online dalliances, especially (but not exclusively) since he’s not actually an elected official. But with Weiner and Spitzer entering the political arena again, we’re back to chatter on sex-related scandals. The human drama of the Weiner story is so attention-grabbing because of its extensive electronic documentation alongside its many unanswered questions, an open field ripe for our own projections. Did he betray his family? Or is it a non-traditional marriage? Speculation is cheap. But while it’s always necessary to take a stand when people’s rights may be violated, there’s another counterbalancing value to apply, and that is minding our own damn business.

I grew up in Barney Frank’s Massachusetts. If ever there was a sex scandal that transgressed the taboos of the time, Barney Frank had it cornered. Then he went on to spend 17 more fruitful and celebrated years in Congress. Like many other politicians who have successfully moved past sex scandals, Frank had developed a reservoir of goodwill through his work before the incidents. The opinions about him that mattered were the ones about his political record, not the politics of his love life. It’s easy to distract ourselves with politicians’ personal lives because that’s something we think we have in common with them, a foothold for making sense of their capacity for loyalty and common sense. That said, I’d never want to be married to a Congressman and I couldn’t begin to imagine my way into the mind of someone who would. When it comes to politicians who don’t make their careers by policing what happens in other people’s bedrooms, it’s worth inspecting the actual motivations behind our inclination to police theirs. I was shocked when Weiner stepped down. I can only assume there were circumstances beyond the aptly titled twit pics, since politicians have weathered much worse and refused to resign, even when, unlike Weiner, their deeds involved dereliction of their actual jobs.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...