Author Archives: Yona Zeldis McDonough

May 19, 2017 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Handbag History: How Judith Leiber Came to Create Her Famous Purses

The impetus for Judith Leiber’s game-changing minaudières, exquisite mini-handbags, came not from a carefully thought-out and executed design plan, but from a blooper. Let’s go back to the beginning though: born Judith Peto and raised in Budapest, the fabled handbag designer first studied chemistry in London (to prepare for a career in cosmetics) and then apprenticed at the Hungarian Jewish firm of Pessl, where she learned to cut and mold leather, make patterns, frame and stitch handbags. She was the first woman graduated to master craftswoman, and the first woman to join the Hungarian Handbag Guild in Budapest.

The impetus for Judith Leiber’s game-changing minaudières, exquisite mini-handbags, came not from a carefully thought-out and executed design plan, but from a blooper. Let’s go back to the beginning though: born Judith Peto and raised in Budapest, the fabled handbag designer first studied chemistry in London (to prepare for a career in cosmetics) and then apprenticed at the Hungarian Jewish firm of Pessl, where she learned to cut and mold leather, make patterns, frame and stitch handbags. She was the first woman graduated to master craftswoman, and the first woman to join the Hungarian Handbag Guild in Budapest.

When the Nazis put her country in a chokehold, the company was shut down, but Judith was able to escape the war and, in 1947, moved with her husband, American-born Gerson Leiber, to New York. She soon found work with the fashion house Nettie Rosenstein and rose steadily through the ranks. Mamie Eisenhower wore a Leiber-designed Nettie Rosenstein bag to the presidential inauguration, putting Leiber squarely on the fashion map. After 12 years with Rosenstein, Judith went out on her own, forming Judith Leiber handbags in 1963. She created some 3,500 handbags in such materials as leather, suede, needlepoint, fur and Lucite. But the bags that arguably made her name and her reputation were the jewel-encrusted minaudières that Leiber began making in the late 1960s when an order of gold-plated brass frames arrived damaged; in order to salvage them, she used rhinestones to cover the discoloration. The rest is handbag history, as the current Museum of Art and Design exhibition Judith Leiber: Crafting a New York Story (April 4, 2017 to August 6, 2017) can attest.

- No Comments

May 9, 2017 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

This Jewish Cowgirl Never Got the Blues

Photo courtesy of the Witte Museum

Question: What do Sandra Day O’Connor, Georgia O’Keefe, Patsy Cline, Annie Oakley and Frances Rosenthal Kallison have in common? Answer: They’re all inductees in the National Cowgirl Museum and Hall of Fame. And Kallison, who died in 2004 and was inducted posthumously, was the first Jewish woman ever to join these ranks.

A third-generation Texan and the only child of Mose A. Rosenthal and Mary Neumegan, Kallison was born in 1908 and grew up in Fort Worth, riding the horses that hauled her family’s furniture wagons. According to Hollace Ava Weiner, writing in the Western States Jewish History, “The city’s Jews were mostly haberdashers, liquor distributors, saloonkeepers, livery men, tailors, grocers and junkmen, although three of the founding fathers operated legitimate theaters.”

Young Frances went to synagogue first in a horse and wagon and then, because her mother was one of the first women in Fort Worth who learned to drive, a Studebaker.

- No Comments

April 20, 2017 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Maira Kalman’s Mother’s Closet Looks Nothing Like Yours

Long before Martha Stewart and Marie Kondo showed up on the scene, there was Sara Berman (1920-2004), an avatar of order who might have taught even those two domestic goddesses a thing or two. Berman, mother of artist Maira Kalman, is now the subject of an exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art that will run from March 6 through September 5, 2017. Or rather, it’s Berman’s closet, recreated by Kalman and her son Alex, that is the subject; the artfully arranged and preternaturally tidy shelves and hanging rods offer us a privileged view of Berman, literally, from the inside out.

Long before Martha Stewart and Marie Kondo showed up on the scene, there was Sara Berman (1920-2004), an avatar of order who might have taught even those two domestic goddesses a thing or two. Berman, mother of artist Maira Kalman, is now the subject of an exhibit at the Metropolitan Museum of Art that will run from March 6 through September 5, 2017. Or rather, it’s Berman’s closet, recreated by Kalman and her son Alex, that is the subject; the artfully arranged and preternaturally tidy shelves and hanging rods offer us a privileged view of Berman, literally, from the inside out.

Nestled in between a spacious and low-slung room designed and decorated by Frank Lloyd Wright and the ornate dressing room of Arabella Worsham-Rockefeller, the closet represents Berman’s life from 1982 to 2004, when, as a divorced woman, she inhabited a studio apartment at 2 Horatio Street in Manhattan. Shoes, clothes, linens, beauty products, luggage, and other necessities are organized and arranged with unerring precision, exactitude and love. From this collection, humble and yet somehow sacred, we can read between the lines of the story outlined in the wall notes composed by Kalman and her son:

- 2 Comments

February 6, 2017 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Reclaiming the Character Lilith–for a Young Audience

Illustration by Arna Baartz

Lilith, this publication’s namesake, doesn’t seem the most likely subject for a children’s book. And yet Monette Chilson, an award-winning writer whose work “celebrates the feminine in God and God in the feminine” has chosen to examine and explain the mythological figure for a young audience. Chilson, author of Sophia Rising: Awakening Your Sacred Wisdom Through Yoga has also contributed to numerous anthologies as well as yoga publications. Her quest along spiritual paths led her to feature the character of Lilith in this book, where her haunting, elegant text has been paired with Arna Baartz’s lush and colorful illustrations.

- No Comments

January 30, 2017 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

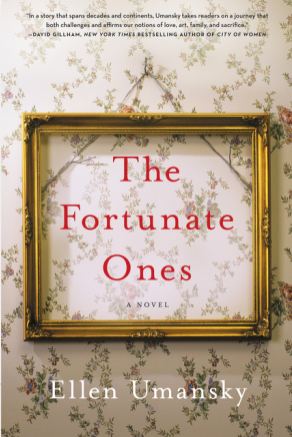

“The Fortunate Ones” — An Excerpt from Ellen Umansky’s New Novel

Back in summer 2011, Lilith published Take the A Train to Scotland, from a novel-in-progress by Ellen Umansky. The novel, now called The Fortunate Ones, has undergone a sea change (Umansky says that the section that appeared in Lilith did not make it into the final version of the novel) and is poised to make its debut on February 14.

Back in summer 2011, Lilith published Take the A Train to Scotland, from a novel-in-progress by Ellen Umansky. The novel, now called The Fortunate Ones, has undergone a sea change (Umansky says that the section that appeared in Lilith did not make it into the final version of the novel) and is poised to make its debut on February 14.

The story begins in 1939 in Vienna, and as the specter of war looms over Europe, Rose Zimmer’s parents are desperate to flee. Unable to escape themselves, they manage to secure passage for their young daughter on a kindertransport, and send her to live with strangers in England. When the war is finally over in 1946, a grief-stricken Rose attempts to build a life for herself. Alone in London, she becomes increasingly focused on trying to retrieve a bit of her lost childhood: the Chaim Soutine painting her mother had held precious.

Many years later, the painting finds its way to America. In modern-day Los Angeles, Lizzie Goldstein has returned home for her father’s funeral. Newly single and unsure of her path, she carries a burden of guilt that cannot be displaced. Years ago, as a teenager, Lizzie threw a party at her father’s house with unexpected but far-reaching consequences. The Soutine painting that she loved and had provided lasting comfort to her after her own mother had died was stolen, and has never been recovered. This painting will bring Lizzie and Rose together and ignite an unexpected friendship that excavates painful and long-held secrets. Below is an excerpt from The Fortunate Ones:

- No Comments

December 27, 2016 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

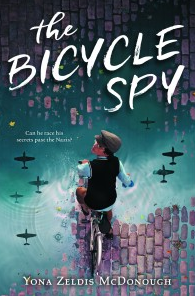

Across the Gender Lines: Writing Historical Fiction that Appeals to Boys and Girls

I’ve always thought of myself as a girly-girl writer. Although I’ve 10 biographies for kids that appeal to both boys and girls—many of them in the popular Who Was… series—my real love is girl-friendly stories; no fewer than five of my children’s books have the words doll or doll house in their titles. I’m also especially partial to stories involving Jewish girls, as the protagonists of The Doll With the Yellow Star, The Doll Shop Downstairs and The Cats in the Doll Shop will attest. If there was a problem here, I failed to see it and would have been happy to keep spinning my Jewish maidele stories as long as there were audiences for them.

I’ve always thought of myself as a girly-girl writer. Although I’ve 10 biographies for kids that appeal to both boys and girls—many of them in the popular Who Was… series—my real love is girl-friendly stories; no fewer than five of my children’s books have the words doll or doll house in their titles. I’m also especially partial to stories involving Jewish girls, as the protagonists of The Doll With the Yellow Star, The Doll Shop Downstairs and The Cats in the Doll Shop will attest. If there was a problem here, I failed to see it and would have been happy to keep spinning my Jewish maidele stories as long as there were audiences for them.

But a chance meeting with an editor from Boys’ Life produced the first crack in my frilly, feminine facade.

- No Comments

December 12, 2016 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Familial Contempt and Delicious Komish Broyt

My grandmother Tania had nothing but contempt for her mother-in-law, Toibe Breittleman. In Tania’s view, the woman was coarse, vulgar and had questionable morals. My grandfather’s mother did not have it easy. When her husband left Russia in search of the better life promised by the lady with the lamp, Toibe remained behind in their dirt-floored home with three small children to raise. There was a single overcoat that they took turns wearing, and she freely gave the children cigarettes to help stave off the hunger pangs; my grandfather began to smoke, with her blessing, at the age of eight. Her desperation—and resourcefulness—drove her to seek work in hotel where she met friends in higher places—gentlemen, army officers—whom she charmed and entertained in ways that were perhaps not entirely kosher. These men supplied food, money and cigarettes and it was her rumored association with them that followed her to America and made my grandmother decide she was a “loose woman.”

Tania, in shorts, standing with my mother who was about 11 in this photo.

Toibe’s husband died but she managed to get along on her own. She was a mover and shaker in her small community of Detroit Jews; she organized elaborate picnics and charged people to attend; the money she raised was donated to help other immigrants like herself. She dyed and curled her hair, wore make up every day and never went anywhere without high heeled pumps. Her dressing table was filled with glass bottles of scent and aromatic unguents, and a flounced, beribboned boudoir doll sat on her bed. After buying a new dress, she would immediately cut out the neckline to expose a more daring swath of decollatage, and then, as if that weren’t enticement enough, sewed sequins all over the bodice. When Tania, then in her twenties, purchased a rather daring pair of Bermuda shorts, Toibe ran right out and purchased an identical pair of her own.

Privately, my grandmother shuddered in horror. Her mother-in-law was a floozy, pure and simple. And yet she had to acknowledge that Toibe was a something of a magician in the kitchen, known for her cooking and baking—which she did in her trademark high heels. These were skills my grandmother prized and which she had not learned from her own mother, Miriam.

Where Toibe had been literally, dirt poor, Miriam’s life back in Russia had been quite different. Her husband, my maternal great-grandfather, was a tanner, an occupation that was considered revolting—the animal skins were softened with a mixture that contained large quantities of urine. There were many professions to which Russian Jews were denied access but tanning was not one of them, possibly because it was so disgusting few people wanted to do it. My great-grandfather became a successful and wealthy man, and my grandmother, the second youngest of twenty-two children (Miriam was possessed of a Biblical fertility) recalled a fine house with parquet floors, crystal chandeliers, and velvet drapes. There was a piano, on which her older sisters were given lessons, and a room for dancing, for they had those lessons too. Some of her brothers went to a military academy. Miriam did not cook for her enormous family; she had servants for that.

But this life of ease and affluence came to an abrupt and savage end when my great-grandfather left for a business trip from which not he, but his bloodied corpse returned, shrouded in a canvas mail sack. Shocked and grief-stricken, Miriam swallowed poison; my grandmother spoke of the “burns around her mouth.” But Miriam was more resilient than she knew—she did not die. Instead she rallied, intent on bringing the five children remaining at home to America. Then Revolution broke out, making Miriam even more desperate to escape. She left her two tiny daughters—my grandmother was six, her younger sister four—while she went out to sell the contents of her home in order to book passage for the trip; she stood mattresses in front of the windows, many of them now shattered, to keep rocks and stones from being hurled in during her absence. Silver, jewelry, crystal, porcelain—all sold, all gone. She kept only five silver soup spoons, and tucked them deep into the recesses of her bag, where they remained until she reached America.

Tania with my uncle.

The polar opposite of Toibe, Miriam was prim, reserved and modest. Her gray hair was always secured in a neat bun. She wore plain, cloth coats, lace up shoes and unadorned leather handbags in two colors only, navy or black, and white blouses that she periodically boiled on the stove in bleach-laced water. For special occasions, she donned a strand of tiny red coral beads and coral earrings.

Yet my grandmother wanted to learn to cook, and especially bake, and so she had to set aside her disdain and turn to her mother-in-law. And Toibe, who was well aware of her daughter-in-law’s contempt, grudgingly said yes, which was how Toibe came to teach my grandmother to make the crunchy, twice baked cookies that were called komish broyt—almost bread.

My meticulous grandmother was an apt pupil and may have even outdone her teacher. Her cookies, studded with walnuts and raisins, and dusted with cinnamon sugar, were thin, light, crisp and delicious. She made them for all the Jewish holidays, brought them to Shabbos dinners, bris celebrations and shivas. When my mother lived in Israel as a young woman, my grandmother wrapped the cookies individually in tissue paper and packed them in tins that she mailed overseas, where they would arrive safely, with scarcely a cracked one in the batch. She taught my mother to make them, though my mother, more bohemian artist than balbusta, would either cut them too thick, or make what to to my grandmother would have been unthinkable alterations—chocolate chips if she had no raisins, peanuts in lieu of walnuts. These cookies were a staple of my childhood and as a young married woman, I began to bake them too; they quickly became a favorite of my own family.

Miriam is long gone now. So are Toibe and my grandmother Tania. The two women who rarely saw eye to eye were somehow united in the kitchen. The recipe and the silver spoons are their conjoined legacy, all that remains of a vanished world. I’ve given the recipe to my daughter Kate—she is the fifth generation of women in our family to have it—and the spoons will be hers one day too. I hope she’ll bring them along into whatever new life she makes for herself; I’d like to think that the spirits of Toibe and Tania will be watching.

Toibe and Tania’s Komish Broyt

4 cups flour

2 teaspoons baking powder

1/2 teaspoon baking soda

4 eggs

1/2 cup orange juice

1 cup oil

1cup sugar

1 teaspoon vanilla

3/4 cup white raisins, plumped with boiling water for 10 minutes, then drained.

3/4 crushed walnuts

Cinnamon sugar to taste

Mix dry ingredients first; gradually fold in wet ingredients, raisins and nuts. When batter has been blended, refrigerate for 30 minutes. Then use batter to form a loaf in a pan, dust with cinnamon sugar and bake for 30 minutes @ 350 degrees. Let cool entirely and with a serrated knife cut in thin slices and bake again at 325 degrees, turning to brown evenly on both sides. Check often to make sure they do not burn.

- No Comments

November 3, 2016 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Yes, These Famous Ballerinas Are Jewish

Back in the 1970’s, I was part of a tribe, one of the many, pale slender ballet girls that walked the avenues—Seventh, Eighth, Broadway—where so many of New York City’s dance studios were then located. With our hair scraped back into punishing buns, and our oversized bags in which we lugged our paraphernalia, we were instantly recognizable, especially to each other, and we displayed a devotion to our art that was almost religious in its single-mindedness and its fervor. Class six days a week, sometimes twice daily in the summer; student rush tickets for performances at Lincoln Center and City Center in the evenings; high school, with its geometry exams, field hockey games and debate teams a mere blur—this was how I spent my formative years. And then, in a blink, it was over—but that is another story. Suffice it to say that although my life veered off in a different direction, my love for the beautiful rigors and rigorous beauties of that early training remained unchanged. My first novel, The Four Temperaments, was set in the ballet world I’d left behind, and even though it was written three decades later, the book became a waiting vessel into which I could pour all the passion of my past.

Back in the 1970’s, I was part of a tribe, one of the many, pale slender ballet girls that walked the avenues—Seventh, Eighth, Broadway—where so many of New York City’s dance studios were then located. With our hair scraped back into punishing buns, and our oversized bags in which we lugged our paraphernalia, we were instantly recognizable, especially to each other, and we displayed a devotion to our art that was almost religious in its single-mindedness and its fervor. Class six days a week, sometimes twice daily in the summer; student rush tickets for performances at Lincoln Center and City Center in the evenings; high school, with its geometry exams, field hockey games and debate teams a mere blur—this was how I spent my formative years. And then, in a blink, it was over—but that is another story. Suffice it to say that although my life veered off in a different direction, my love for the beautiful rigors and rigorous beauties of that early training remained unchanged. My first novel, The Four Temperaments, was set in the ballet world I’d left behind, and even though it was written three decades later, the book became a waiting vessel into which I could pour all the passion of my past.

So when I chanced upon the New York Times obituary of the ballerina Yvette Chauviré, who died in her home in Paris at the age of 99, I read it with more than a passing interest. The obit mentioned another dancer of the period—Solange Schwarz. Solange was clearly French. But Schwarz? Could have been German. Or Jewish. Intrigued, I dug up a little more.

- No Comments

October 26, 2016 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Surviving in “The Waiting Room”

The Waiting Room, shortlisted for the Voss Literary Prize, unfolds over the course of a single, life-changing day, but the story it tells spans five decades, and three continents. As the daughter of Holocaust survivors, Dina’s present has always been haunted by her parents’ pasts. She becomes a doctor, emigrates from Australia to Israel, and builds a family of her own, yet no matter how hard she tries to move on, their ghosts keep pulling her back. A dark, wry sense of humor helps Dina maintain her sanity amid the constant challenges of motherhood and medicine, but when a terror alert is issued in her adopted city, her usual coping skills begin to fray.

The Waiting Room, shortlisted for the Voss Literary Prize, unfolds over the course of a single, life-changing day, but the story it tells spans five decades, and three continents. As the daughter of Holocaust survivors, Dina’s present has always been haunted by her parents’ pasts. She becomes a doctor, emigrates from Australia to Israel, and builds a family of her own, yet no matter how hard she tries to move on, their ghosts keep pulling her back. A dark, wry sense of humor helps Dina maintain her sanity amid the constant challenges of motherhood and medicine, but when a terror alert is issued in her adopted city, her usual coping skills begin to fray.

Interlacing the present and the past over a span of 24 hours, The Waiting Room explores just what it means to endure a day-to-day existence in a country defined by perpetual conflict and trauma. Author Leah Kaminsky e-chats with Lilith Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough and describes her own complicated journey across continents—and back.

- 1 Comment

October 13, 2016 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

From Stolen Silverware to Politicos: An Interview with Michelle Brafman

These 17 luminous narratives reveal the secrets of a mismatched cast of politicos, filmmakers, housewives, real estate brokers and consultants, all tied to one suburban neighborhood. Linked through bloodlines and grocery lines, they respond to life’s bruises by grabbing power, sex, or the family silver. As they atone and forgive, they unmask the love and truth that hop white picket fences. One of the stories, “Sylvia’s Spoon,” was a Lilith fiction contest winner in 2006, and it’s still stunning.

These 17 luminous narratives reveal the secrets of a mismatched cast of politicos, filmmakers, housewives, real estate brokers and consultants, all tied to one suburban neighborhood. Linked through bloodlines and grocery lines, they respond to life’s bruises by grabbing power, sex, or the family silver. As they atone and forgive, they unmask the love and truth that hop white picket fences. One of the stories, “Sylvia’s Spoon,” was a Lilith fiction contest winner in 2006, and it’s still stunning.

Author Michelle Brafman e-chats with Lilith’s Fiction Editor, Yona Zeldis McDonough, about the stories that inform the stories.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...