Author Archives: Yona Zeldis McDonough

November 7, 2019 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Chutzpah: A Former Israeli Defense Intelligence Commander’s Guide to Business and Parenting

In her new book, Chutzpah: Why Israel is a Hub of Innovation and Entrepreneurship (HarperCollins), entrepreneur extraordinaire Inbal Arieli offers a penetrating analysis of how Israeli culture, especially mandatory military service, informs the dynamics of business. She talks to Lilith Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about where she’s been and what lessons she’s learned along the way.

Yona Zeldis McDonough: How has your experience in the Israeli Defense Force Intelligence unit influenced your work in the Israeli tech sector?

Inbal Arieli: I had the privilege to be selected, at the age of 17+, to serve in the Intelligence 8200 unit, the Israeli equivalent of the N.S.A. Through the unique screening process this unit applies, I learned that what I already know is less important than what I could potentially learn. This approach, of focusing on talent potential, versus existing knowhow or experience, still influences the way I assess team members and candidates in the ventures I lead in the tech sector.

During my military service, I was part of a team of young people who came from different backgrounds, applied different approaches to problem solving and addressed challenges in various ways. This taught me that cross-pollination of ideas, and diversity, are extremely valuable for any team.

At the age of 19, I was appointed as team leader. I was the commander of a team of 15 soldiers, some older than I, definitely more experienced and knowledgeable. I then learned that leadership traits are much more critical than formal hierarchy. My team members, colleagues and commanders at 8200 are still a substantial portion of my professional network to date, more than two decades after finalizing my military service.

As a team, we faced intel challenges which seemed at first impossible to achieve. But given their importance and consequences for the security of Israel, we just had to overcome them. In 8200 I learned that there is no such thing as impossible.

All of these lessons I experienced and learned at 8200, and many more, have influenced my professional career. For me, as someone who is interested in technology, the Israeli tech sector was a natural choice, as it was for many friends from the unit. However, these lessons are applicable to any sector.

- No Comments

September 20, 2019 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

“Vera Paints a Scarf”- Honoring the Life and Designs of Vera Neumann

For Proust, a tea-soaked madeleine was the portal to memory, but for me it was the show “Vera Paints a Scarf” at Manhattan’s Museum of Art and Design. The show celebrates not only the scarves but also the tableware, clothing, posters, stationery, and paintings created by the eponymous designer. Back then, I didn’t even think to associate the name, scrawled in loose, jaunty script, with an actual person. It seemed like the name of a product, only slightly more resonant than Kleenex or Mattel, though I did like the little ladybug (more on that later) that was part of the logo.

Instead, I was captivated by the bright colors, the breezy, slightly insouciant style, the sheer joy of the designs, which were easy mix of natural elements like trees, flowers—lots of flowers—birds, insects (that ladybug again) fruits, and vegetables, along with more abstract patterns, some sinuous and lyrical like her paisleys, others more geometric or linear. Of the ladybug she said that it “means good luck in every language.” Both her palette and her aesthetic felt fresh and distinctly modern, the shifts and tunics designed for girls like me, or maybe the girl I aspired to be—think 1960s model Twiggy in one of those little dresses and a pair of go-go boots and you get the idea.

I don’t know how or when I lost track of Vera, though I do recall occasionally encountering the scarves in my perpetual second-hand-shmatte hunt, when such a discovery would be accompanied by a whiff of nostalgia and even melancholy. So walking into the show at MAD was a thrill that brought it all rushing back—color, the whimsy, the echo of the girl I was when I first discovered her.

MAD Museum

- No Comments

September 19, 2019 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

When a Toy Dog Became a Wolf and the Moon Broke Curfew…

In this new memoir, Hendrika de Vries’ writes of the dark days in Nazi-occupied Amsterdam as a child, years as a swimming champion, young wife and mother in Australia, and a move to America in the sixties. She talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis about how the brutality of her childhood fostered a strength and resilience she has been able to draw upon ever since.

YZM: How did your mother’s decision to join the Resistance and harbor Nel, a young Jewish woman, affect you as a girl?

YZM: How did your mother’s decision to join the Resistance and harbor Nel, a young Jewish woman, affect you as a girl?

HDV: At the time that my father was deported to Germany, I was an only child surrounded by friends and cousins who all had siblings, and I longed for my own brother or sister. I do not have a clear memory of how I felt when my mother decided to join the Resistance. In a way it seemed a natural progression, because we regularly spent time at the home of the family where members of the Resistance movement met. And when my mother told me we were going to hide a Jewish girl, I liked the thought that I would have an adopted older sibling. I was told that her name was Nel, but in order protect her secrecy I was not given her last name.

After she moved in with us, Nel and I formed a sisterly closeness and often slept in the same bed. In the manner of an older sister, she gave me a sweet diminutive nickname “Hennepiet,” and wrote about our “happy” time together in a poignant verse for the friendship album that girls my age carried around in those days. A copy of her verse with the nickname “Hennepiet” appears in my memoir.

Having been a daddy’s girl for the first five years of my life, I now learned about the comfort and unique pleasure of being in an all-female household. In my memory, my mom and my secret “stepsister” were always brewing pots of coffee and talking. If I close my eyes even today, I can still smell the rich aroma of coffee that permeated our home, and being in the company of their female bantering and laughter made me feel safe. I remember my mom bringing out a coffee-table-sized Old Testament copy of the Bible that had been in her family all her life. It showed full-page sepia illustrations of the Hebrews escaping slavery in Egypt. There was one of the parting of the Red Sea, of course, but the image I liked best was of Miriam, Moses’ sister, and other women dancing as they celebrated their freedom with tambourines. My mom, Nel and I would dance around our dining-room table clanging spoons and shouting “freedom” until my mom shushed us. I loved having an older sister. But I could not talk about her. She had to be our big secret. I could never figure out at six years old why the Nazis wanted to kill her, or might kill my mother and me because we were hiding her. I believe this confusion set me on my lifelong path to try to understand human behavior and my own eventual spiritual quest for the divine.

- No Comments

September 11, 2019 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

South America’s Jewish Prostitutes (Sex Slaves, Really)

It was shocking—and horrifying—to learn that more 100,000 Jewish women from Eastern Europe had been forced into sexual slavery in South America by other Jews willing and eager to exploit them. Talia Carner’s new novel, The Third Daughter (HarperCollins) dramatizes this disgraceful chapter in Jewish history, and she talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about the very contemporary impact this story continues to have.

YZM: How did you come to this subject?

TC: I had first become aware of the magnitude of global and historical sexual exploitation at the 1995 International Women’s Conference in Beijing. An aging Filipina with an operatic voice cried to high heavens about her enslavement by the Imperial Japanese Army during WWII as one of thousands of girls and women captured in the Pacific Rim. Then a teenager, she had been imprisoned in a “comfort station” to serve the soldiers’ sexual needs.

The plight of kidnapped women forced into sexual slavery touched me deeply, and in my head it was narrated by the Filipina’s haunting voice. In subsequent years I read about sex trafficking and attended presentations by UN-affiliated NGO’s in New York City, where I live.

A snippet of the history of girl victims lured from beleaguered Eastern European Jewish communities to South America had come to my attention through Hebrew literature. My interest was reawakened when I stumbled upon a short story by Sholem Aleichem, “The Man from Buenos Aires,” (now in my own translation on my website). I googled the subject and was appalled to learn how much information was hiding in plain sight about Zwi Migdal, the legal trafficking union. Yet, the estimated 150,000 to 220,000 Jewish women exploited by its members had been forgotten, lost in the goo of history.

- 1 Comment

August 26, 2019 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

A Twist on Doctor-Patient Confidentiality

Radiologist and debut novelist Heather Frimmer tells the story of a mother planning her daughter’s wedding just as she receives a diagnosis of breast cancer in her new novel Bedside Manners. Frimmer talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about how her medical training shapes her life as a writer.

YZM: How did your own training as a doctor influence the writing of this novel?

HF: I work full time as a radiologist specializing in breast imaging. I interpret mammograms, discuss results with patients and perform breast biopsies.

Joyce’s story was inspired by the thousands of breast cancer patients I’ve had the honor of caring for. I used my observations to make Joyce’s journey as authentic and emotionally resonant as possible. Some of the events in Marnie’s story were inspired by or loosely based on situations either I or my friends experienced on the wards during training. I wanted to explore the doctor-patient relationship from both sides. Choosing both a mother and daughter as the protagonists allows the characters to witness and experience both sides of the relationship alongside the reader.

YZM: Why did you make Marnie a surgeon rather than a radiologist?

HF: I would have loved to make Marnie a radiologist, but I knew it wasn’t the right choice. Radiologists stare at computer screens in dark rooms while drinking endless cups of coffee—the opposite of dramatic. Making Marnie a surgeon allowed me to put her in more precarious and emotional situations and raise the stakes for her a lot more.

YZM: The men in the novel respond very differently to the news of Joyce’s cancer than the women; care to comment?

HF: That’s such an interesting observation. This wasn’t a conscious choice, but I think the difference comes from my personal experience. The men in my life tend to underplay their emotional reactions, only getting upset in the most dire of circumstances. The exception to this rule would be my wonderful husband who wears his emotions on his sleeve without shame.

YZM: During the course of the novel, Marnie struggles with her decision to marry a non Jewish man. Were you making a larger statement about intermarriage between Jews and Gentiles?

HF: My goal was not to be prescriptive about intermarriage, but rather to raise questions so readers can think about the issue for themselves. Spouses will inevitably differ in countless ways and learning to negotiate those differences is crucial for a successful marriage. As an obsessive reader, if I can remain happily married for nearly seventeen years to someone who reads less than one book a year, then anything is possible. The keys are open communication, dedication, and acceptance on the part of both partners.

YZM: Do you think you’ll use your medical background in writing your next novel?

HF: I am finishing edits on my next novel which follows a male neurosurgeon with an addiction to pills who makes the decision to operate on his sister-in-law’s brain. The story explores how this decision affects not only the course of both of their lives, but of their entire family as well. I love the way my publicist describes this book—” a complex tale of addiction, love, and survival on the operating table.” While this novel does take place in the world of medicine, it strays much further from my area of expertise. This one required a lot more research to get the details right.

YZM: What’s one question that you wished I’d asked but didn’t?

HF: I like credit to the authors who have inspired me to become a writer. Lisa Genova, the author of Still Alice and Every Note Played, along with several other wonderful novels, has been my major inspiration. I love how the way she uses her expertise as a neuroscientist to explore the details of a specific neurologic disease, its emotional ramifications and the ways the disease impacts everyone in the patient’s sphere. I’d be hard pressed to pick a favorite—her books are all that good.

I also deeply admire Jennifer Weiner’s writing—I faithfully read her novels the day they are released. The way she can make a story hilarious and compulsively readable while addressing serious topics is truly admirable. Her newest novel, Mrs. Everything, just came out in June and is her most ambitious novel yet. She’s truly outdone herself with this one.

- No Comments

July 10, 2019 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

A Novelist Brings Jewish Women to the Forefront of Crime Stories

A Jewish woman married to Wyatt Earp? A Jewish woman cleaning up after a murder committed by her brother, a criminal with ties to the Jewish mafia? These are the kinds of stories that novelist Thelma Adams loves to tell.

A Jewish woman married to Wyatt Earp? A Jewish woman cleaning up after a murder committed by her brother, a criminal with ties to the Jewish mafia? These are the kinds of stories that novelist Thelma Adams loves to tell.

She talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about how she finds her subjects and what they yield in her novels.

- No Comments

June 11, 2019 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Conversation with a Curator: Avery Exhibit Features Works by Artist Wife and Daughter

“Summer with the Averys [Milton/Sally/March],” a remarkable show at the Bruce Museum in Greenwich, presents the work of american painter Milton Avery alongside that of his wife Sally and their daughter March, who were both artists in their own right.

A Jewish girl born in 1902, Sally Avery (née Michel) studied painting at the Arts Students League and met Milton in 1924; she was 22 and he was 39. They married in 1926 and embarked upon an unusual artistic life together.

Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough talks to Stephanie Guyet (who assisted Professor Kenneth E. Silver in mounting the show) about the special role Sally played in her husband’s life and career.

Sally Michel Swimming Lesson, 1987

- No Comments

June 7, 2019 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

“Jade Lily” Imagines Jewish Refugees Who Found Home in Shanghai

Vienna, 1938. It’s clear to the Bernfelds that they are no longer welcome in their city and they have to flee. But where? No one wants or will accept the refugees…no one except the Chinese that is, and so the family, or what remains of it, heads for Shanghai. Novelist Kirsty Manning talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about how she accidentally stumbled upon this bit of Jewish history and what she did to bring it to life in The Song of the Jade Lily.

Vienna, 1938. It’s clear to the Bernfelds that they are no longer welcome in their city and they have to flee. But where? No one wants or will accept the refugees…no one except the Chinese that is, and so the family, or what remains of it, heads for Shanghai. Novelist Kirsty Manning talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about how she accidentally stumbled upon this bit of Jewish history and what she did to bring it to life in The Song of the Jade Lily.

- No Comments

May 14, 2019 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

The Meaning and Value of Humor: An Interview with Marilyn Simon Rothstein

In Lift and Separate and Husbands and Other Sharp Objects (both from Lake Union Publishing) humor is the lens through all of life’s mishegas is viewed. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough asks author Marilyn Simon Rothstein what it means to be funny, and why it’s more essential now than ever.

YZM: Have you always been considered funny?

YZM: Have you always been considered funny?

MSR: When I was growing up in Flushing, New York, a terrible name for a wonderful community where there were two ethnic groups—Orthodox Jews and Conservative Jews—my family sat around a wrought iron kitchen table and discussed one important topic—other people. Being funny was the way to get everyone’s attention.

YZM: Do you think that Jewish humor, and in particular Jewish women’s humor, is its own category?

MSR: All humor is based on observation. So, Jewish humor is based on what a member of the Jewish community observes. I feel that my first book, Lift And Separate, is very Jewish.

- No Comments

May 2, 2019 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

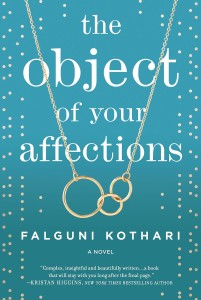

The Object of Your Affections: What’s a Baby Between Friends?

Two best friends undergo a bitter falling out and a tearful coming back together. But this is no ordinary rapprochement—because one of the women asks her friend to be the surrogate who carries her child. Author Falguni Kothari talks to Lilith’s fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about the complex, delicate nature of such a relationship, and how it set the plot for her new novel in motion.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...