by Yona Zeldis McDonough

“Jade Lily” Imagines Jewish Refugees Who Found Home in Shanghai

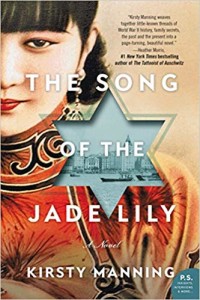

Vienna, 1938. It’s clear to the Bernfelds that they are no longer welcome in their city and they have to flee. But where? No one wants or will accept the refugees…no one except the Chinese that is, and so the family, or what remains of it, heads for Shanghai. Novelist Kirsty Manning talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about how she accidentally stumbled upon this bit of Jewish history and what she did to bring it to life in The Song of the Jade Lily.

Vienna, 1938. It’s clear to the Bernfelds that they are no longer welcome in their city and they have to flee. But where? No one wants or will accept the refugees…no one except the Chinese that is, and so the family, or what remains of it, heads for Shanghai. Novelist Kirsty Manning talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about how she accidentally stumbled upon this bit of Jewish history and what she did to bring it to life in The Song of the Jade Lily.

YZM: What attracted you to the story of Jews who fled to Shanghai during WWII?

KM: I’m ashamed to admit that I had no idea about the story of Jews who fled to Shanghai during WWII before I went to Shanghai on a holiday with my children. I’d arranged for us to cram into a small hotel room in the cheaper part of Shanghai known as Hongkou (formerly Hongkew). Enroute to a shop selling lemon iced tea, I noticed a rusted Star of David inset into a red doorway.

YZM: What was this symbol doing in the middle of an old longtang laneway?

A visit to the nearby Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum revealed the story of the Shanghai Jews to me. I was gobsmacked.

Today, millions of people are seeking refuge and still our borders and hearts remain closed. It’s a universal, heartbreaking story. And as a writer my job is to ask questions. The big one to me in Shanghai was: Why haven’t the lessons of history taught us to treat people better?

In Shanghai, ideas for The Song of The Jade Lily started to bloom. I started to think about friendship and loyalties, the price of love and the power of war. How hardship and courage can shape us. How does being a refugee – being stateless – shape identity? The unexpected bargains that are made when we make our own rules. What does it mean to be generous as a person? And as country? What is our duty?

YZM: What kind of numbers are we talking about?

KM: Numbers in academic texts vary, but a visit to the Shanghai Jewish Refugees Museum revealed that Shanghai had opened its doors to over 20,000 refugees fleeing Europe. With the exception of the Dominican Republic, Shanghai was the only port in the world refugees could enter at the time without a visa.

YZM: Why do you think this story is less familiar to Americans?

KM: Honestly, I’m not sure. But I get a sense that there are just so many Holocaust stories—and so much trauma—that it takes years to heal and share these stories. This is a poignant moment in history, and the more we learn, the more see we need to find out. Perhaps part of it is that people who lived through WW2 are getting older and we are hungry for their wisdom and insights. We seek their stories now, rather than turn away in horror. We need to learn from these stories for the next generation.

I think the story of Shanghai Jews is less familiar to people in most parts of the world, not just America, because I get so much feedback from readers who say that before The Song of The Jade Lily, they had no idea about the Jewish history in Shanghai. They then go on to say they have started to look into memoirs and the research around that era to find out more, which is just an honour.

Others contact me to say they had a family member in Shanghai. A number of times ex-refugees who lived in the Shanghai Ghetto, or the French Concession, have personally written to thank me for taking the time to write about this moment of history.

YZM: How did you conduct your research and how long did it take?

KM: I spent about six months reading memoirs by people who lived in Shanghai during that era, then I went to Shanghai on a research trip. In Shanghai I did a Jewish Tour, a food tour, visited the Jewish Refugee Museum, walked the gardens, visited Art Deco buildings, took a historical tour of the French Concession and ate my bodyweight in xia long bao dumplings.

My first stop, however, was with the Jewish Holocaust Museum and Research Centre in Melbourne and the Sydney Jewish Museum who sold me texts and scratched their heads with a bemused smile when they enquired why I would want this material. Both sets of staff were generous with their time and resources, and the Melbourne contact put me in touch with Sam Moshinsky, author of Goodbye Shanghai and a Russian Jew who grew up in Shanghai’s French Concession. He was delighted to meet me over coffee and tell me about his time in Shanghai and he then went on to read a draft of the book and answer questions ranging from Jewish rituals, to the tiny minutia of life in Shanghai under the Occupation. He introduced me to Horst Eisfelder, a former Austrian refugee who spent time in the ghetto. It turned out Horst had arrived in Shanghai on the same Italian ocean liner, Conte Verde, as my imaginary Romy … and his family had owned the café in the ghetto she visits regularly, Café Louis. Both gentlemen were enormously generous and patient as I tried to walk in another person’s shoes and capture a small part of the Shanghai era and Sam emailed me to say:

‘Like Horst, I was very pleased to be asked to share our individual, and unusual, stories of our Shanghai experiences. All of us from that milieu believe that we grew up in a unique city at a most unique time in history, never to be repeated!’

For Li and the Ho family, I read a lot about Chinese resistance to the Japanese occupation and the different ways that could manifest itself. Some did it via art, some in journals and some, like Wilma Ho through theatre. Traditional Chinese Medicine was also being stamped out during this era and I thought the herb lore was a wonderful way to express the mood of the era.

For Zhang, I visited and then studied the Suzhou gardens. Chinese Gardens are extraordinary. I love both the contemporary and the ancient ones. These deceptive, simple gardens forced me to focus, change perspective. They teach us the Confucian philosophies of order and balance and the Taoist teachings of simplicity and restraint.

YZM: In the 1950’s and 1960’s, mah jong was quite popular with Jewish women; do you think this had to do with the Jewish/Shanghai connection?

KM: Possibly. So many of the Shanghai Jews were repatriated to the USA after the war. I know that every Jewish person I have interviewed have said how grateful they were to the local Chinese people for their generosity. They shared living quarters in the ghetto, Chinese New Year meals and there was a mutual exchange of customs. The adults played mah jong together, and the children played soccer and other games in the laneways.

YZM: The novel centers on secrets that are kept from generation to generation—do you feel that revealing these secrets was necessary for the characters to thrive and grow?

KM: Certainly. There’s so much research around now about trauma being passed along in families. Also the damage that is done when people have no way to process their grief. People keep secrets because they think it for the best, but it sometimes leads to a yawning gap in knowledge for the next generation.

I spoke to Holocaust survivors to find out information about Shanghai and the war. But what I got was so much more. I watched their eyes light up when they talked about their grandchildren and great-grandchildren, how important it is to be anchored in a community. They spoke of their grief and loss too, of course, and of having to be refugees not once, but twice. I think the biggest secret I discovered really was how it is possible for the heart to heal, and how these refugees were able to live with the horrors and happy moments of their past, but be positive about the future.

Sometimes I think for our modern generation it can be easy to be caught up with striving for success. But of course, the real secret is that a successful life is one which is wholehearted, generous and hopeful. The most important things in life are family, friendship, community, hope and love.