Author Archives: Yona Zeldis McDonough

May 6, 2014 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Jill Smolowe on Four Funerals and a Wedding

Jill Smolowe, author of “Four Funerals and a Wedding.” (Courtesy Phyllis Heller)

Jill Smolowe, a journalist and memoirist, had her own annus horribilis, only hers lasted a year and a half. In that short span of time, she endured the deaths of her beloved husband, Joe, her mother-in-law, and her own mother and sister. Smolowe kept waiting to fall apart in the wake of such loss, and yet she didn’t. Some untapped reserve of strength and resilience kept her going, and able to find meaning and even joy again. In this interview, she shares her hard-won wisdom about grieving with Lilith fiction editor Yona Zeldis McDonough.

YZM: What made you decide to write and publish your book Four Funerals and a Wedding?

JS: Like so many Americans, I had a set idea that grief involves specific stages. Yet I went through no denial, anger, bargaining or depression. Instead, as I lost my husband, sister, mother, and mother-in-law over a period of 17 months, my focus was on putting one foot in front of the other and figuring out how to reconnect with the joy in life. The more friends told me I was “amazing,” the more I wondered if there was something wrong or abnormal about my sorrow. Then I came across the work of George Bonanno, one of the country’s leading bereavement researchers. That’s when I learned that Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s five-stage cycle of grief has long since been discredited. (She intended her cycle to apply to the dying, not the bereaved.) Research from the last 20 years identifies three distinct groups: those who are overwhelmed by grief upwards of 18 months; those who recover within 18 months; and those who return to normal functioning within six months, and even within days. This last group is labeled “resilient” and–surprise, surprise–these people constitute a majority of the bereft. My book aims both to put a face on this group and to challenge misconceptions and assumptions about grief.

- No Comments

April 23, 2014 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

To Dye, or Not to Dye? That Is the Question

http://www.flickr.com/scottbillings

It began predictably enough: the first gray threads I found in my hair when I hit my thirties. The threads soon turned to ribbons, but I had just had a baby (my second) and was in no shape to deal with it. Gray was interesting, I reasoned. Gray was subtle, intellectual and hip. Soon enough the baby became a toddler and her older brother started kindergarten. I woke up one morning and decided that the gray was not intellectual, not subtle and definitely not hip. Gray was just—old.

I mounted my campaign. First in my arsenal was a series of home treatments that took their inspiration from reruns of “I Love Lucy.” There was the Five Minute Color Solution. It worked all right; it just looked like I had looked like I dipped my head in large vat of shoe polish. I dumped it and moved on to various mousses and gels that stained the grout in my bathroom shower, more towels and pillowcases than I care to think about and left ominous drops, black as primordial ooze, on my dining room floor. Forget the do-it-yourself route. I needed professional help.

- 3 Comments

April 7, 2014 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Jewish Woman, Muslim Man, and What This Unlikely Literary Pairing Produced

A Jewish woman collaborates on a book with a Muslim man? Sounds like the start of a joke—except that it’s anything but. When writer and teacher Susan Shapiro was forced to undergo physical therapy for an injured back, she met a young therapist whose personal story soon had her riveted. She drew it out of him, page by page, and the result, The Bosnia List, just published in March by Penguin. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough talks to Shapiro about this highly unlikely pairing and the unexpected insights it yielded.

A Jewish woman collaborates on a book with a Muslim man? Sounds like the start of a joke—except that it’s anything but. When writer and teacher Susan Shapiro was forced to undergo physical therapy for an injured back, she met a young therapist whose personal story soon had her riveted. She drew it out of him, page by page, and the result, The Bosnia List, just published in March by Penguin. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough talks to Shapiro about this highly unlikely pairing and the unexpected insights it yielded.

YZM: What initially drew you toward Kenan Trebincevic?

SS: I tore two ligaments in my lower back and Kenan was my physical therapist.

One day, he told me to do leg lifts and went to help another patient. As a journalism teacher I always carry a stack of student papers. The exercises were boring so I took out papers to grade. Kenan got annoyed I wasn’t paying attention to the workout. He looked over at the essays and asked sarcastically “What I did on my summer vacation?” in his Eastern European accent. I said, “Actually, my first assignment is to write three pages on your most humiliating secret.”

He laughed and said, “You Americans. Why would anyone do that?”

I said, “It’s healing.” And I added also that my students want to get published in the New York Times and write books. That night he emailed to see if I was okay, which I thought was very menschy. I sent him a poignant piece my student Danielle Gelfand published in the New York Times about how she and her mother, a Holocaust survivor, eat bacon cheeseburgers on Yom Kippur, as a way to cope with her father’s suicide on that day 17 years earlier. I think that piece inspired Kenan.

- No Comments

February 20, 2014 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Print is Dead

Print is dead, or so the pundits have been telling us. And yet, in this electronic age when reading matter has been whittled down to fit on a smart phone, along comes Fig Tree Books, a brand new print publisher whose focus is the Jewish American experience. A blend of original titles and revered classics, Fig Tree is the brainchild of Fredric Price, a drug developer, and it will be launching in early 2015. Lilith’s fiction editor, Yona Zeldis McDonough, talks to Fig Tree senior editor Michelle Caplan about Fig Tree’s goals, ambitions and how this “nimble” imprint plans to take advantage of “the new normal.”

Print is dead, or so the pundits have been telling us. And yet, in this electronic age when reading matter has been whittled down to fit on a smart phone, along comes Fig Tree Books, a brand new print publisher whose focus is the Jewish American experience. A blend of original titles and revered classics, Fig Tree is the brainchild of Fredric Price, a drug developer, and it will be launching in early 2015. Lilith’s fiction editor, Yona Zeldis McDonough, talks to Fig Tree senior editor Michelle Caplan about Fig Tree’s goals, ambitions and how this “nimble” imprint plans to take advantage of “the new normal.”

YZM: Can you talk about the decision to start a new publishing company at a time whenever everyone is bemoaning the decline of print in general and books in particular?

MC: My publisher, Fredric Price, has had a successful entrepreneurial career developing drugs for rare diseases. While he has no professional background in publishing, he is an avid reader and has established two longstanding groups that read and discuss Jewish books and essays. He decided to focus his efforts toward creating the new home for the best fiction of the American Jewish experience. All of the changes that have occurred in publishing in the last several years create a window of opportunity for a small, focused, nimble imprint like Fig Tree Books. We can take advantage of the new normal because we do not have a pre-existing structure, organization or operating method that is struggling to adapt to the new publishing environment. Fred feels that the publishing industry is ripe for the same type of approach that he used when developing, marketing and selling “orphan” drugs. Rather than following the industry in trying to develop blockbuster drugs for highly visible illnesses like hypertension, he built very successful businesses by focusing on drugs for small populations. While Jews represent a small fraction of the American population, we are a significant percentage of the purchasers of literary fiction.

YZM: What drew you to this editorial position at Fig Tree?

MC: Fred has responded to the need for a publisher to champion emerging and unique voices and created a place where writers about the American Jewish experience can launch their work into the world with visible celebration and support. I have spent most of my career as a freelance editor, consultant and ghostwriter of fiction, creative non-fiction and film scripts. I’ve mentored both aspiring and established writers and I believe Fig Tree will be the home of American Jewish fiction writing for the 21st century. We will have a combination of original works plus what we call re-released classics, books that were previously published and are now out of print but are relevant and exciting to readers today.

YZM: What is the significance of the name Fig Tree?

MC: Our name is inspired by a letter from George Washington to the Hebrew Congregation in Newport, Rhode Island in 1790, in which he says “May the children of the Stock of Abraham, who dwell in this land, continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other Inhabitants; while every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and fig tree, and there shall be none to make him afraid.” We feel that this event in American history captures the spirit of our democracy in which Jews and other previously religiously persecuted groups have flourished. The wisdom of our first president set the stage for a milieu of tolerance and acceptance, enabling Jews to thrive, and we could think of no better metaphor for the beneficence of the Jewish Experience in America.

YZM: Will there be any particular emphasis on writing by Jewish American women?

MC: We are interested in publishing novels of excellence that deal with the American Jewish experience and are agnostic as to an author’s gender, age, race and even religion. It is a rich mosaic that can be approached by anyone with a gift for writing and a topic that appeals both to Jews and others. We certainly do hope to attract beautifully written books by women writers. Our editorial staff is comprised of women with a keen eye for quality writing.

- 1 Comment

February 4, 2014 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

What DID Nora know?

Linda Yellin is a funny lady. To wit, her new novel, What Nora Knew,” is crammed with snappy one-liners, snarky apercus and a whole lot of good-humored sass. Whether intentionally or not, Yellin has joined ranks with Ephron in turning out a particular kind of humor, one that is specific—if not unique to—Jewish women. She talks to Lilith Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about concealed vibrators, the enduring appeal of rom-coms and the nuances that separate the funny girls from the boys:

Linda Yellin is a funny lady. To wit, her new novel, What Nora Knew,” is crammed with snappy one-liners, snarky apercus and a whole lot of good-humored sass. Whether intentionally or not, Yellin has joined ranks with Ephron in turning out a particular kind of humor, one that is specific—if not unique to—Jewish women. She talks to Lilith Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about concealed vibrators, the enduring appeal of rom-coms and the nuances that separate the funny girls from the boys:

Yona Zeldis McDonough: You have a background in advertising; how did you transition to writing fiction?

Linda Yellin: I’m sure there are people who’d say advertising is fiction, but that theory aside, my first novel was ninety percent true. So it was only sorta-fiction. I changed all the main players’ names to keep my relatives from getting mad at me. I didn’t want to get un-invited to the family seders.

The next book, The Last Blind Date, was a memoir, so that was technically non-fiction. But I guess none of my cousins got offended because they’re still speaking to me. What Nora Knew is a novel, although Nora Ephron and her movies and insights are real, so I guess I’m still transitioning into writing fiction.

YZM: Your protagonist, journalist Molly Hallberg, has had some pretty entertaining assignments: learning to dance like a Rockette and sneaking vibrators through security scanners. Any of these drawn from real life experiences?

LY: Absolutely. Molly and I have a lot in common. Most of her assignments are ones I’ve done for MORE magazine. Including one where she spends a day wearing kegel underpants. (One-inch silicone plug in the crotch…you can figure out the rest.)

The vibrators was my favorite assignment. There were three of them – all “disguised” like cosmetics: a lipstick; a mascara; and a blusher brush. I stood in line at the Family Court building in New York thinking: it’ll be really great for the story if I get busted for doing this. (Security guard: “Would the owner of the vibrating mascara please step out of line?”) But all along I was praying that I’d pass through. When it got down to story-versus-mortification, I was more afraid of mortification. Molly Hallberg’s braver than me.

YZM: What Nora Knew is an homage not only to Nora Ephron but to the whole Hollywood tradition of romantic movies. Can you say more about that?

LY: There are certain constructs and expectations in romantic movies. We probably know from the get-go who the heroine will end up with, but if you care about the characters, you want to travel along with them and root for their success. Whether it’s Meg Ryan and Tom Hanks, or Meg Ryan and Billy Crystal, or Jennifer Lawrence and Bradley Cooper – romantic comedies are journeys with happy endings, and who doesn’t love that? And who doesn’t love Nora Ephron’s romantic comedies?

YZM: Do you consider Ephron a quintessentially Jewish humorist and if so, why?

LY: Her humor is quintessentially relatable, so it also covers Christianity, Buddhism, Atheism; you name it. But there is a wry, sardonic point-of-view in all of Nora Ephron’s writing that certainly feels Jewish. An oy-vey-can-you-believe-this quality. It’s the same one I grew up with while my aunts and uncles and cousins were debating life over corned beef and smoked fish.

YZM: How would you describe the differences between male and female humorists?

LY: Subject matter. Our humor leans toward relationships and emotion. Guys tend to vamp more on guy-stuff. Sex, sports, things that explode. Don’t hold me to this opinion, though. For sure, there’s a PhD candidate out there whose doctoral thesis would totally disagree.

YZM: What, in the end, did Nora know?

LY: Plenty. That’s why it was so much fun to write this novel.

- No Comments

January 23, 2014 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Who are the fools here?

The expression still waters run deep could have been coined for Joan Silber. In person, she is charming, modest and even self-effacing; on the page, she bristles with feeling–humor, anger and lust are just part of her impressive range—and her capacity for creating sympathetic, likable characters who nevertheless do some highly unlikable things is one of her greatest gifts. In a conversation with Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough, Silber shares some of what she’s learned over her long and rich writing career.

The expression still waters run deep could have been coined for Joan Silber. In person, she is charming, modest and even self-effacing; on the page, she bristles with feeling–humor, anger and lust are just part of her impressive range—and her capacity for creating sympathetic, likable characters who nevertheless do some highly unlikable things is one of her greatest gifts. In a conversation with Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough, Silber shares some of what she’s learned over her long and rich writing career.

YZM: Let’s talk about the concept of linked stories. What does this form allow that others don’t? How does such a book differ from a novel or a more conventional story collection?

JS: This is the third book of linked stories I’ve done. There are lots of things I love about the form. It lets me treat material from different angles–a minor character in one is major in another—and I can work different sides of a theme. In this book, for instance, we see the dilemmas in being a fool for an idea, and the disadvantages in not being one.

Linked stories used to be considered an apprentice form, written by writers who really wanted to do novels. (Not true for me–I’d done three novels first.) Now it has its own popularity—there are definitely more linked collections around.

One of my favorite things about the form is that characters who are dislikeable in one story can be humans we’re allied with in another. (Liliane, for example.) There’s a beautiful quote from John Berger in which he says, “Never again shall a single story be told as if it were the only one.”

- No Comments

December 30, 2013 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Women and Mobsters in the Jazz Age

Chicago and the jazz age have always fascinated Renee Rosen so it seemed almost preordained that she would set her first novel, Dollface, in that particular milieu. A former advertising copywriter with a serious yen for fiction, Rosen let her invented characters rub shoulders with real ones like Al Capone and Hymie Weiss—who, by the way, was not Jewish. But she talks to Lilith’s fiction editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about mobsters who were Jewish—and about the women who loved them.

Chicago and the jazz age have always fascinated Renee Rosen so it seemed almost preordained that she would set her first novel, Dollface, in that particular milieu. A former advertising copywriter with a serious yen for fiction, Rosen let her invented characters rub shoulders with real ones like Al Capone and Hymie Weiss—who, by the way, was not Jewish. But she talks to Lilith’s fiction editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about mobsters who were Jewish—and about the women who loved them.

YZM: How did you make the leap from advertising copywriter to novelist?

RR: I was actually writing fiction before I got into advertising, so for me it was more about pretending to care about my work as a copywriter when my heart was so clearly vested in my own writing. I remember I would get up at 4 a.m. and write until about 8 a.m. when it was time to get ready to go into the office. I’d get home and try to put in another couple of hours in the evening. There were many a days when I wrote though my lunch hour, jotted down notes on my legal pad during meetings and my weekends and days off were always devoted to writing.

YZM: Can you describe your research process for Dollface?

RR: I started with the basics and spent many hours at the Harold Washington Library poring over actual newspaper clips from historical events in the 1920s. Because I live here in Chicago, I was also able to visit the actual landmarks where these events took place. So I’ve been to the site of the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre and I’ve seen the bullet hole in Holy Name Cathedral, etc. Once I had a real feel for the lay of the land, I started looking for people to interview who had ties to 1920s gangsters. That resulted in meeting with a man whose father had been a bookie for Al Capone which was fascinating. I also had lunch with Al Capone’s great niece. There were other people I spoke to as well and some who developed “Chicago Amnesia” and refused to talk to me, which I also found very interesting. To think that some 70 or 80 years later, they were still standing by their oath of silence. The mob runs deep!

- No Comments

November 19, 2013 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

She’s a Writer. She’s Very Nosy.

In Lisa Gornick’s haunting second novel, Tinderbox, a young nanny recently arrived from Peru rattles both the composure and professional ethics of psychoanalyst Myra Gold. But this is not new territory for Gornick, who is on the faculty at the Columbia University Center for Psychoanalytic Training and Research and a graduate of the writing program at New York University. Her first novel, A Private Sorcery, revolved around Saul Dubinsky, a sensitive, dedicated psychiatrist who turns to drugs after the suicide of a patient. Gornick recently chatted with fiction editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about the ways in which the fields of literature and psychotherapy feed each other, the Jewish experience filtered through the lenses of Morocco and Peru, and the redemptive power of fire.

In Lisa Gornick’s haunting second novel, Tinderbox, a young nanny recently arrived from Peru rattles both the composure and professional ethics of psychoanalyst Myra Gold. But this is not new territory for Gornick, who is on the faculty at the Columbia University Center for Psychoanalytic Training and Research and a graduate of the writing program at New York University. Her first novel, A Private Sorcery, revolved around Saul Dubinsky, a sensitive, dedicated psychiatrist who turns to drugs after the suicide of a patient. Gornick recently chatted with fiction editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about the ways in which the fields of literature and psychotherapy feed each other, the Jewish experience filtered through the lenses of Morocco and Peru, and the redemptive power of fire.

YZM: You are a novelist with training and degrees in clinical psychology and psychoanalysis; can you talk about how fiction writing and psychology come together (if they do) in your work?

LG: Last summer, I stayed at a bed and breakfast in Maine. Next to the main house was an enormous old barn that stretched towards the back of the property like a railroad car. It was sealed tight as a drum, but my antennae went up: inside that barn was a story. My husband watched me reading the literature about the property (the house had once been the home of the Woolworth brothers who’d raised prize harness race horses and entertained the likes of Clark Gable), examining the photographs in the album left out in the breakfast room, striking up a conversation with the current owner, and, of course, ultimately asking if he would open the barn doors for me. “She’s a writer,” he apologized to the owner. “She’s very nosy.”

Although handled with more tact and in the service of healing, nosy equally describes the psychoanalyst, also always on the alert for the moments when emotions peek out from the crevice between words and their cadence, for the pulse points in a patient’s stream of words, for the places where a gentle inquiry, perhaps just the repetition of the patient’s words, will open a door. In an essay “Analyzing and Novelizing,” I gave the much altered example of a remote scientist who, after many months of treatment, used the phrase, “When we lived in Old Millbrook,” and how it was my writerly ear that sensed the tragic story behind these seven syllables.

Freud, whose early immersion in literature and writing suggests he might with a different turn of events have become a novelist himself, was deeply ambivalent about creative writers, a subject I’ve written about in an essay “Freud and the Creative Writer.” On the one hand, he credited creative writers with having already discovered everything analysts would learn in their consultation rooms. On the other hand, he viewed creative writers as on the verge of psychosis. Putting aside these idealizing and devaluing extremes, analysts and creative writers clearly share many tools — free association, attentiveness to language, dreams. Most centrally, both work with narratives, how they are constructed and unfold, an initial tale often hiding a more complicated and taboo story yet to be told.

- No Comments

November 12, 2013 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

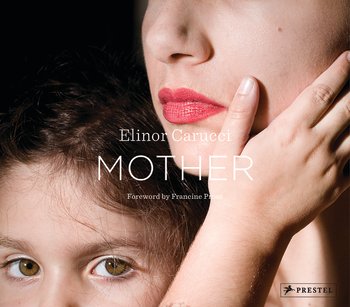

Mother, Photographer

Don’t let the name fool you: Elinor Carucci was born in Jerusalem and studied at the Bezalel Academy of Art in Jerusalem; she moved to New York City the day after graduation to pursue her career as a photographer. The first few months were very difficult; she was on her own, and struggling with the many cultural differences. But she persevered and was soon approached by the prestigious Ricco/Maresca Gallery and offered a solo show and representation; she is now represented by the Sasha Wolf Gallery. Her first book, Closer, was published in 2002, the same year she was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship, and it was followed by Diary of a Dancer in 2005. Mother, her third book, just came out from Prestel, and she chatted with Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about the tender and intimate collection of photographs that comprise the volume.

Don’t let the name fool you: Elinor Carucci was born in Jerusalem and studied at the Bezalel Academy of Art in Jerusalem; she moved to New York City the day after graduation to pursue her career as a photographer. The first few months were very difficult; she was on her own, and struggling with the many cultural differences. But she persevered and was soon approached by the prestigious Ricco/Maresca Gallery and offered a solo show and representation; she is now represented by the Sasha Wolf Gallery. Her first book, Closer, was published in 2002, the same year she was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship, and it was followed by Diary of a Dancer in 2005. Mother, her third book, just came out from Prestel, and she chatted with Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about the tender and intimate collection of photographs that comprise the volume.

YZM: Tell me about your earliest experiences with photography.

EC: I was 15 years old when I picked up my father’s camera. I then very intuitively walked into my mother’s bedroom and started taking pictures of her as she was waking up from her afternoon nap. in the coming weeks I continued taking pictures of her and then of my other family members and myself. I saw so much more with my camera, looking through it, looking at the photographs, it was another way of communicating with the people I love most and later with many more people.

YZM: Where do you find your inspiration?

EC: In feelings and seeing. In life, in art, in looking with attention and depth. Looking and feeling…and trying to understand and go deeper. In photographs, films and TV shows, painting, books. The streets, the people I love, looking at families in the subway, talking to a stranger, comforting a friend.

YZM: The subjects in your most recent body of work, Mother, are your children and your husband. How do you bring being a mother and being a photographer together?

EC: With a lot of hard work and focus. I had to set priorities, and give up a lot of my time with friends and free time for now.

- No Comments

November 5, 2013 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

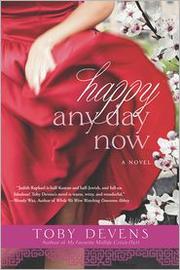

Our Long Lineage of Seers and Fortune-Tellers. Who Knew?

By her own description, Toby Devens was a “Broadway baby”‘ who had a successful early career of acting on stage and television. But by the age of twelve, she had hung up her dancing shoes and picked up a pen. Early efforts included fairy tales, detective stories in the manner of Nancy Drew and a staged version of Little Women. Later, she turned to poetry and short fiction; she also wrote restaurant reviews and theater criticism. Her first novel, My Favorite Mid-Life Crisis (Yet) came out in 2006 and is now followed by Happy Any Day Now. Devens chatted with Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about what Jewish and Korean moms have in common, her lifelong passion for music and the particular pleasures of finding love in the middle ages.

By her own description, Toby Devens was a “Broadway baby”‘ who had a successful early career of acting on stage and television. But by the age of twelve, she had hung up her dancing shoes and picked up a pen. Early efforts included fairy tales, detective stories in the manner of Nancy Drew and a staged version of Little Women. Later, she turned to poetry and short fiction; she also wrote restaurant reviews and theater criticism. Her first novel, My Favorite Mid-Life Crisis (Yet) came out in 2006 and is now followed by Happy Any Day Now. Devens chatted with Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about what Jewish and Korean moms have in common, her lifelong passion for music and the particular pleasures of finding love in the middle ages.

Yona Zeldis McDonough: You’ve created an unusual character–a Korean-Jewish female, Judith Soo Jin. Why?

Toby Devens: Sometimes stories come about in strange and wonderful ways. Happy Any Day Now began when my granddaughter was born and I felt this surge of longing to find out about my own maternal grandmother. She died eight months before my birth. I’m named for her and when I went to Ellisisland.org and saw her listed on a 1900 ship’s manifest, I felt incredibly close to this woman I’d never known. That’s when I started asking my family questions about her: how she became American, learned the language, weaved the old the world with the new. As I put together my grandma’s story, I realized that much of the immigrant experience was universal, and I wanted to write about that. But how? The answer came with a friend request on Facebook from a relative I barely knew: the daughter of my first cousin and his Asian wife. Seeing that young woman’s photo—the beautiful blending of two cultures—produced my eureka moment, and my protagonist Judith Soo Jin Raphael, a cellist with the Maryland Philharmonic. In Happy Any Day Now, we meet Judith as she’s approaching her 50th birthday and her past invades her present to make magic and mischief.

- 4 Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...