by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Jewish Woman, Muslim Man, and What This Unlikely Literary Pairing Produced

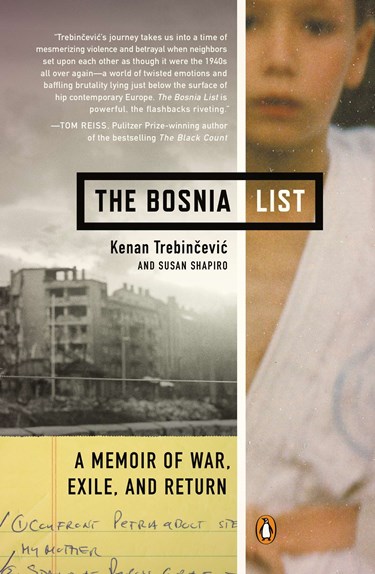

A Jewish woman collaborates on a book with a Muslim man? Sounds like the start of a joke—except that it’s anything but. When writer and teacher Susan Shapiro was forced to undergo physical therapy for an injured back, she met a young therapist whose personal story soon had her riveted. She drew it out of him, page by page, and the result, The Bosnia List, just published in March by Penguin. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough talks to Shapiro about this highly unlikely pairing and the unexpected insights it yielded.

A Jewish woman collaborates on a book with a Muslim man? Sounds like the start of a joke—except that it’s anything but. When writer and teacher Susan Shapiro was forced to undergo physical therapy for an injured back, she met a young therapist whose personal story soon had her riveted. She drew it out of him, page by page, and the result, The Bosnia List, just published in March by Penguin. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough talks to Shapiro about this highly unlikely pairing and the unexpected insights it yielded.

YZM: What initially drew you toward Kenan Trebincevic?

SS: I tore two ligaments in my lower back and Kenan was my physical therapist.

One day, he told me to do leg lifts and went to help another patient. As a journalism teacher I always carry a stack of student papers. The exercises were boring so I took out papers to grade. Kenan got annoyed I wasn’t paying attention to the workout. He looked over at the essays and asked sarcastically “What I did on my summer vacation?” in his Eastern European accent. I said, “Actually, my first assignment is to write three pages on your most humiliating secret.”

He laughed and said, “You Americans. Why would anyone do that?”

I said, “It’s healing.” And I added also that my students want to get published in the New York Times and write books. That night he emailed to see if I was okay, which I thought was very menschy. I sent him a poignant piece my student Danielle Gelfand published in the New York Times about how she and her mother, a Holocaust survivor, eat bacon cheeseburgers on Yom Kippur, as a way to cope with her father’s suicide on that day 17 years earlier. I think that piece inspired Kenan.

The next session came. Kenan waved, rushed over, hooked me up to electrodes and, when I was flat on my back, handed me HIS three pages. It was about how he’d recently returned from Bosnia, two decades after the ethnic cleansing campaign that almost killed his Muslim family. When he was 12, his beloved karate coach came to his door with an AK-47 and shouted, “You have one hour to leave or be killed.” He took Kenan’s father and brother to a concentration camp. All their friends and neighbors turned on them.

YZM: Why did you want to help him tell his story?

SS: My family lost relatives in Eastern Europe during World War II. I’d written for a lot of Jewish publications and reviewed many Holocaust memoirs for the New York Times Book Review and a syndicated column I’d done at Newsday. When I read Kenan’s story, I thought: he’s the male Muslim Anne Frank. In 1992. Who lived to tell the story.

He lived in Queens near his brother and his dad, who’d had a stroke. Kenan took care of him, refusing to ever put him in a nursing home. He was such a good, hard-working kid, who’d had such a tough life. He was very sensitive at work, taking good care of patients of all ages. I felt like he’d been through hell and he deserved a break.

YZM: How did it turn into a book?

SS: I gave him an editor’s email and told him to use my name. Those first three pages wound up in the New York Times Magazine, picked up in the International Herald Tribune and the Best American Essay collection, and a William Morris agent was interested in Kenan’s memoir.

I told him to write a 3-page flashback scene next. He said he couldn’t remember, then handed me 43 pages the next day. I recommended memoir classes and ghostwriters and editors he could work with. But he said he’d never told anyone the whole story before. English wasn’t his first language, he’d never written before and had studied only science. He would only do the book with me, if I’d help him.

YZM: As a Jewish woman embarked on a project with a Muslim man, did you feel any conflict or apprehension?

SS: Yes. I have many relatives in Israel. Though I’m liberal, after 9/11, living near the World Trade Center, I secretly feared I could become Islamophobic. I decided to avoid talking about religion or politics. That turned out be hilarious–since that’s all we wound up talking about–and writing 300 pages about for the next two years.

We came up with the title “The Bosnia List,” and I asked him if he had any connection with “Schindler’s List.” It turned out it was his late mother Adisa’s favorite movie, which she made him watch with her when they were in Connecticut (where they were sponsored by the Connecticut Interfaith Council).

He suddenly remembered that she told him she wanted to write the story of how they’d survived. But she was too sick with cancer to finish it. We dedicated the book to her.

YZM: Describe the process of working together.

SS: I’m a workaholic who published nine books in the last nine years, including three of my own memoirs. I’d started another project and I teach four night classes every term. Kenan was young. He liked to go to the beach and on vacations. I told him I would only do the book together at my pace—which was quickly. If he wasn’t serious and devoted to working every day and night, forget it.

He’d see patients fulltime from 11:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m., so often he’d give me rough pages. I would flesh them out by interviewing him before and after work, on weekends, and by phone, e-mail and text. I did a crash course on Yugoslavian history. Luckily we’re both driven and have a ton of energy. I joked that within a week I’d turned my mellow Muslim physical therapist into a neurotic Jewish freelance writer. We finished the first draft in nine months.

YZM: Now that the book is about to be published, what do you hope it will achieve?

SS: Last week Kenan told me he had a dream that he was back in Bosnia, where he bumped into an old classmate who’d betrayed him and they were about to get into a fight. Then I showed up and told him not to be stupid, that he had a big future in New York and had to stop fighting. Then his mother woke up from a nap and shook my hand and thanked me for helping him with the book. I was very touched.

We’re having a book party to celebrate what we call “A Jewish/Muslim book of healing.” I think it’s important that Kenan told his story, and sees that Americans are interested in what happened to him. I feel like the book will do good in the world.