Author Archives: Yona Zeldis McDonough

January 12, 2015 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

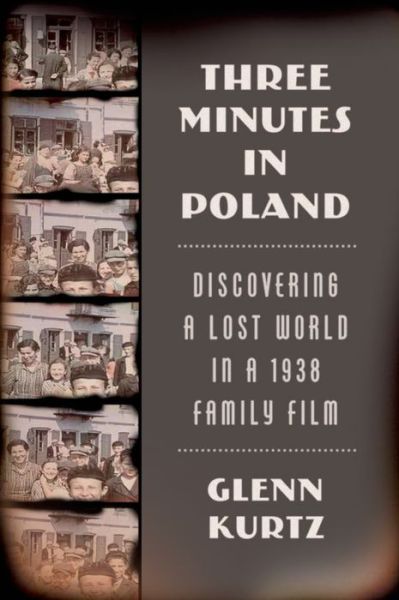

Three Minutes in Poland

When Glenn Kurtz happened upon an old family film in a closet of his parents’ home in Florida, he was intrigued. The film was shot by his grandfather, David Kurtz, during a trip he and his wife made to Europe in 1938—right on the eve of destruction. Kurtz’s initial interest grew into an almost spiritual quest, one in which he was determined to piece together as much as he could about the Polish town of Nasielsk—and the people who inhabited it. The result is the sweeping account in his book, Three Minutes in Poland, both a reverent attempt to document a lost history and a fervent desire to animate it once more. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough chatted with Kurtz by e-mail.

When Glenn Kurtz happened upon an old family film in a closet of his parents’ home in Florida, he was intrigued. The film was shot by his grandfather, David Kurtz, during a trip he and his wife made to Europe in 1938—right on the eve of destruction. Kurtz’s initial interest grew into an almost spiritual quest, one in which he was determined to piece together as much as he could about the Polish town of Nasielsk—and the people who inhabited it. The result is the sweeping account in his book, Three Minutes in Poland, both a reverent attempt to document a lost history and a fervent desire to animate it once more. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough chatted with Kurtz by e-mail.

YZM: How did you research this process of historical reconstruction?

GK: I worked on the book for more than 4 years, though in some sense, the research continues to this day. The images preserved in a photograph or in a film are preserved in a very peculiar way. They are both extraordinarily specific (individual people in a particular place at a specific moment), and at the same time utterly enigmatic. If you don’t already know what or who you’re looking at, the information in the image immediately becomes general, unspecific, and almost mythological (or in the case of old photos and films, nostalgic). Instead of seeing, say, “Chaim Nusen Zwajghaft, gravestone carver in Nasielsk in August 1938,” we see “prewar Polish Jews.” The general description is not inaccurate. But it does not convey information on the same scale as the image itself. It makes the image less specific.

When I first discovered my grandfather’s 1938 home movie, I knew almost nothing about it. I didn’t even know the town in Poland that appears in the film. The great difficulty, then, was to unlock the information contained within the images.

- No Comments

January 8, 2015 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

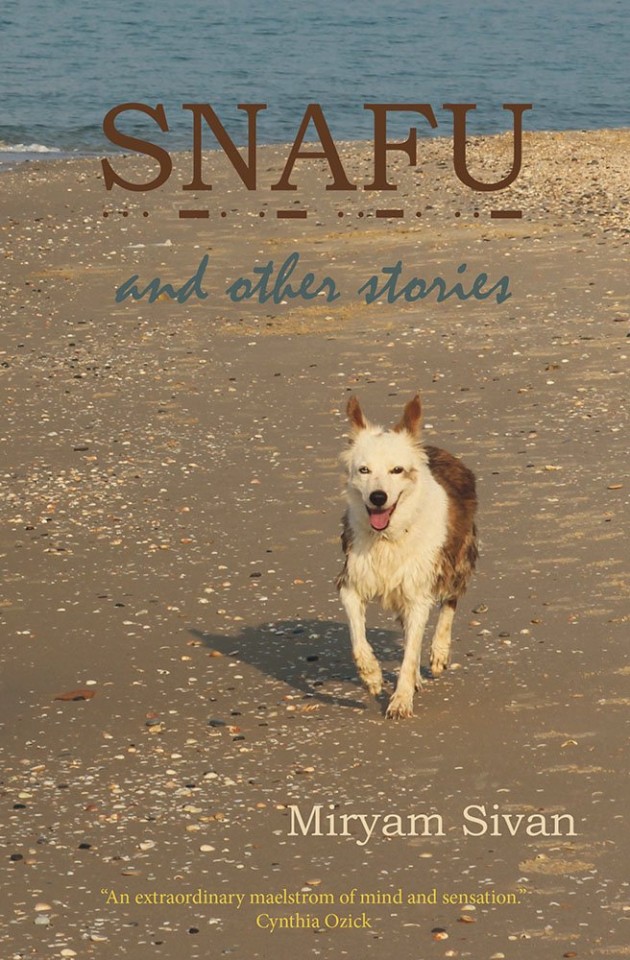

Found in the Lilith Slush Pile

Over a decade ago, Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough received a story called “Roadkill,” submitted unsolicited. The story dealt with the plight of Ella, a 30-ish Israeli woman who accidently hits a dog while driving. The dog’s last moments and subsequent death are woven in with other losses, and other sorrows; altogether it was a haunting, powerful work that appeared in the Spring 2003 issue. Ever since then, McDonough has followed the career of the story’s author. Now spelling her first name with a “y,” Miryam Sivan lives in the Galilee but writes in English. Sivan’s new collection, Snafu, contains “Roadkill,” “City of Refuge” (which appeared in the Spring 2011 issue), and 10 other bristling, animated and highly intelligent stories. McDonough recently caught up with Sivan, who was happy to share her thoughts on “street Hebrew,” the role of dogs in our lives, and the tricky, shifting dance—or sometimes battle—between the sexes.

Over a decade ago, Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough received a story called “Roadkill,” submitted unsolicited. The story dealt with the plight of Ella, a 30-ish Israeli woman who accidently hits a dog while driving. The dog’s last moments and subsequent death are woven in with other losses, and other sorrows; altogether it was a haunting, powerful work that appeared in the Spring 2003 issue. Ever since then, McDonough has followed the career of the story’s author. Now spelling her first name with a “y,” Miryam Sivan lives in the Galilee but writes in English. Sivan’s new collection, Snafu, contains “Roadkill,” “City of Refuge” (which appeared in the Spring 2011 issue), and 10 other bristling, animated and highly intelligent stories. McDonough recently caught up with Sivan, who was happy to share her thoughts on “street Hebrew,” the role of dogs in our lives, and the tricky, shifting dance—or sometimes battle—between the sexes.

YZM: Tell me about living in Hebrew and writing in English.

MS: I just gave a talk about this…. it’s not a simple phenomenon for a number of reasons. When a Jew moves to Israel, she returns not only to her people’s ancient homeland, replete with many wonderful and seriously challenging dimensions, but she also “returns” to Hebrew. Since I don’t write in Hebrew, I experience myself as an artist-outsider. And this creates a kind of dissonance, since I am a Jew in Israel. I belong and don’t belong, simultaneously.

Years ago a German colleague of mine asked me if I was an Israeli writer or an American one. I honestly didn’t know how to answer. Finally I asked him why I had to choose…. why couldn’t I be both? A hybrid — an American writer who writes about Israel, an Israeli writer who writes in English?

- 1 Comment

December 22, 2014 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Lilith Author and her new Sarah Silverman Film Deal!

I always read the Lilith slush pile with a kind feverish, burgeoning hope—maybe this is the story that will make the hair on the back of my neck rise up. Or this one. Or this. Well, back around 2001, I had one of these longed-for experiences when I read a story by an emerging writer named Amy Koppelman. The story was too long for our pages and uncommonly dark, with its depiction of a young mother suffering from post-partum depression who accidently kills her infant and then intentionally kills herself. But I shared it with Lilith’s editor-in-chief Susan Weidman Schneider and she agreed with me about the story’s stark, stinging power, even as she acknowledged that it would not readily fit into our format. I couldn’t give up on it though, so I contacted the writer and asked her if she perhaps had another story we could consider. She did, and Lilith published Koppelman’s story “The Groom” in 2002. It was her first publication and I don’t know which of us was more thrilled and proud. That story that we couldn’t use? It turned out to be the final, harrowing chapter in an altogether harrowing novel, A Mouthful of Air, which was published to critical acclaim by MacAdam Cage in 2003. Koppelman credits the publication in Lilith with giving her the confidence to pursue the agent who led to the sale. Since that time, I have stayed in touch with Koppelman, and was once again thrilled when I learned that her second novel, I Smile Back, has been made into a film starring Sarah Silverman and will be shown in the Sundance Film Festival.

I always read the Lilith slush pile with a kind feverish, burgeoning hope—maybe this is the story that will make the hair on the back of my neck rise up. Or this one. Or this. Well, back around 2001, I had one of these longed-for experiences when I read a story by an emerging writer named Amy Koppelman. The story was too long for our pages and uncommonly dark, with its depiction of a young mother suffering from post-partum depression who accidently kills her infant and then intentionally kills herself. But I shared it with Lilith’s editor-in-chief Susan Weidman Schneider and she agreed with me about the story’s stark, stinging power, even as she acknowledged that it would not readily fit into our format. I couldn’t give up on it though, so I contacted the writer and asked her if she perhaps had another story we could consider. She did, and Lilith published Koppelman’s story “The Groom” in 2002. It was her first publication and I don’t know which of us was more thrilled and proud. That story that we couldn’t use? It turned out to be the final, harrowing chapter in an altogether harrowing novel, A Mouthful of Air, which was published to critical acclaim by MacAdam Cage in 2003. Koppelman credits the publication in Lilith with giving her the confidence to pursue the agent who led to the sale. Since that time, I have stayed in touch with Koppelman, and was once again thrilled when I learned that her second novel, I Smile Back, has been made into a film starring Sarah Silverman and will be shown in the Sundance Film Festival.

The protagonist of I Smile Back is haunted by demons both psychological and chemical; she is addicted to risky, extra-marital sex and cocaine, in equal measure. But Koppelman’s treatment is ever tender, ever humane; though she walks on the dark side, she sees the faint light glowing in every ruined, ravaged heart. We at Lilith could not be more proud of her, and we can’t wait to see what she’ll do next.

- No Comments

November 18, 2014 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Hollywood Princess

Although born and raised in New York City, Dana Aynn Levin always considered herself a California girl at heart. So after graduating from Vassar College, where she studied economics and psychology, she headed out to the land of sunshine, oranges and, of course, movie magic. After a brief detour in DC to earn an MBA, Levin headed back to the beach, where she became a film production accountant working on, in her words, “films you’ve never heard of.” She wrote her first novel at the age of six, and then did not attempt it again until five or so decades later. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough asked Levin to talk about her enduring love for Tinseltown, and how those screen dreams informed the conception and execution of Hollywood Princess.

Although born and raised in New York City, Dana Aynn Levin always considered herself a California girl at heart. So after graduating from Vassar College, where she studied economics and psychology, she headed out to the land of sunshine, oranges and, of course, movie magic. After a brief detour in DC to earn an MBA, Levin headed back to the beach, where she became a film production accountant working on, in her words, “films you’ve never heard of.” She wrote her first novel at the age of six, and then did not attempt it again until five or so decades later. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough asked Levin to talk about her enduring love for Tinseltown, and how those screen dreams informed the conception and execution of Hollywood Princess.

YZM: What’s behind the fascination Los Angeles has always had for you?

DL: The history of my fascination with Los Angeles sounds so hokey and not at all intellectual. It’s rooted in pop culture. Growing up, so much of the music I enjoyed either came from artists based in Los Angeles, (Beach Boys, Eagles, Linda Ronstadt, etc.) or the songs referenced the city. California Dreaming? I was. And when I was trapped in Malibu for two weeks by mudslides my first winter, I laughed at the absurdity of “It Never Rains in California.” Seriously, Albert Hammond? He had obviously never experienced an El Nino.

- 1 Comment

November 11, 2014 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Helena Rubinstein: Beauty Is Power

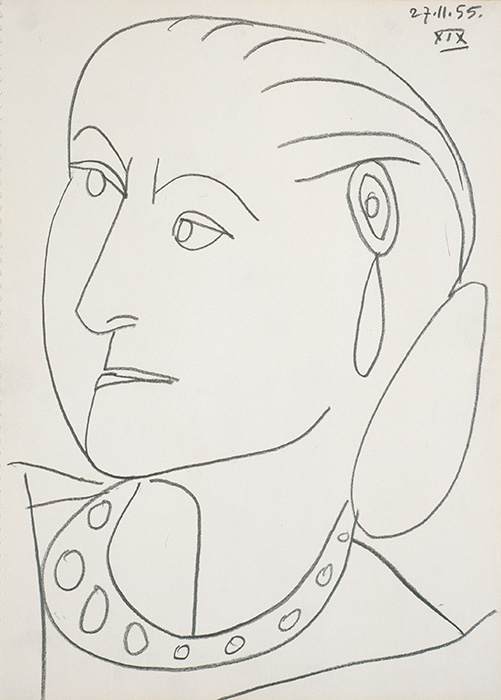

Pablo Picasso, Portrait of Helena Rubinstein XIX 27-11-1955, 1955.

Conté crayon on paper, 17 1/4 x 12 5/8 in. (43.8 x 32.1 cm). Himeji City Museum of Art, Japan. © 2014 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

You knew Helena Rubinstein. That is, even if you didn’t actually know her, you know her type: the smart, feisty, implacably-willed Jewish woman who just goes ahead and does what she wants, no matter what the world tells her. Like others of her ilk—Estée Lauder, Georgette Klinger, Beatrice Alexander and Ruth Handler—she made her name in an arena—cosmetics—where being a woman was an advantage, not a liability. The newly opened show at the Jewish Museum, interdisciplinary in nature, offers a fascinating glimpse into the life the Jewish girl with humble roots in Poland who grew up to become, “a global icon of female entrepreneurship and a leader in art, design, fashion and philanthropy.”

Born in 1872, Rubinstein fled an arranged marriage in 1888. By 1896, she had gone from Krakow to Vienna and then to Australia, where she established her first business. She flat-out rejected the notion that only prostitutes and women of questionable virtue wore make up, and instead built an empire on the premise that wearing make-up was a self-assertive, empowering act, one that allowed a woman to literally create the face that she showed to the world. The title of the show is a tag line from one of Rubinstein’s own advertising campaigns, and the exhibition’s wide-ranging offerings—primarily artwork, but also clothing, jewelry, packaging and advertising, and miniature rooms—demonstrate the many ways that statement can be interpreted.

As a collector, Rubinstein was both canny and idiosyncratic in her taste; her acquisitions include works by Pablo Picasso, Elie Nadleman, Frida Kahlo, Max Ernst, Leonor Fini, Joan Miró, and Henri Matisse and when she was alive, they graced the homes she kept in London, Paris, New York, the South of France and Greenwich, CT. Also represented are 30 pieces from her visionary collection of African and Oceanic art, a collection that ultimately helped to reshape the way this work was viewed—and valued—in the west.

- No Comments

October 22, 2014 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

What the Wicked Witch Taught Her

Taken together, the pieces by Bonnie Friedman in Surrendering Oz: A Life in Essays, just out from Etruscan Press, form an autobiography of sorts, one in which we follow the progress of a shy, bookish Jewish girl as she slowly but surely comes into her own. From the Bronx bedroom she shares with her older sister to the thoroughfares and cities of the wider world, we watch as the girl grows and gains confidence, both as a writer, and as a woman. The essays that chart her growth—she’s now 56—have an internal sequence all their own, determined by their emotional valence, not the calendar. Dorothy from Kansas and Gertrude Stein, Victoria’s Secret and bedbugs—in Friedman’s skilled hands, the quotidian stuff and mess of the world come together in a benign—and even divine—order. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough asked Friedman about the singular faith that infuses every single page of this indelible book:

Taken together, the pieces by Bonnie Friedman in Surrendering Oz: A Life in Essays, just out from Etruscan Press, form an autobiography of sorts, one in which we follow the progress of a shy, bookish Jewish girl as she slowly but surely comes into her own. From the Bronx bedroom she shares with her older sister to the thoroughfares and cities of the wider world, we watch as the girl grows and gains confidence, both as a writer, and as a woman. The essays that chart her growth—she’s now 56—have an internal sequence all their own, determined by their emotional valence, not the calendar. Dorothy from Kansas and Gertrude Stein, Victoria’s Secret and bedbugs—in Friedman’s skilled hands, the quotidian stuff and mess of the world come together in a benign—and even divine—order. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough asked Friedman about the singular faith that infuses every single page of this indelible book:

YZM: Did you write these essays with the goal of gathering them into a book? Or did their coming together in a single volume happen after they had been written?

BF: I wrote these essays over many years, always in the grips of a presiding passion — something I needed to figure out in my own life but that I thought reflected something unspoken or unresolved in the lives of other women. Late in the process I saw that the essays connected up – they all concern how one learns to think for oneself, how one gains possession over one’s own life. Once I saw that, I believed I might have a book.

YZM: You offer a brilliant, feminist interpretation of the film The Wizard of Oz; do you feel its messages have particular meaning for Jewish women?

BF: Historically, shtetl women were allowed take on a larger role in running the family and even the business so as to free up the husband to study Torah, if possible. The spiritual was privileged over the pragmatic, and to some extent this allowed women to take on a more vigorous role out in the world. But gender roles in America were different. I grew up in the Bronx in a Jewish neighborhood, and I marveled at the version of femininity I saw on TV and in old movies, with its demure reticence and picturesque helplessness. It didn’t match up with the way I saw women behaving in the streets and classrooms around me. And yet, of course, television is our school, especially when we are young, and we unconsciously absorb its values. In The Wizard of Oz, Aunt Em talks about how, being a “good Christian woman,” she can’t tell the town bully, Elvira Gulch, what she thinks of her dominating ways. Nor can she advocate for Dorothy. Many of us Jewish girls, to be acceptable, learned to muffle and constrict ourselves.

- 1 Comment

October 7, 2014 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

A “Rescue” Baby, a New Novel

For me, writing a novel usually begins with a character tapping me on the shoulder and whose insistent whisper in my ear urges to me to get the story down, and to get it right. But for my most recent novel, You Were Meant for Me, inspiration came to me in a different way: an actual news event in which a man found a newborn infant on a subway platform and eventually ended up adopting him.

For me, writing a novel usually begins with a character tapping me on the shoulder and whose insistent whisper in my ear urges to me to get the story down, and to get it right. But for my most recent novel, You Were Meant for Me, inspiration came to me in a different way: an actual news event in which a man found a newborn infant on a subway platform and eventually ended up adopting him.

The story would not leave me, and I found myself returning to it again and again in my mind. What had driven that baby’s mother to leave him not in a hospital, police or fire station—safe havens, all—but on a subway platform? And what random stroke of luck or divine intervention averted all the horrific ends to this tale—and there could have been so many—and instead turned it into one of salvation and grace? As I mulled over these questions, it occurred to me that the story was working on another level as well, one that was both mythic and archetypal. The foundling, the infant abandoned and rescued, is motif that occurs over and over in literature and can trace its roots as far back as the Bible. Wasn’t Moses himself a foundling, set in the ark and concealed in the bulrushes by Yocheved, whose fear for his life was so great that she was willing to give him up to save him? And wasn’t Moses rescued by the most unlikely of saviors, an Egyptian princess who found and then raised him as her own?

- No Comments

August 19, 2014 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Tender is the Brisket

Philadelphia-based humorist and freelance writer Stacia Freedman has a knack for one-liners and her snappy new novel, Tender is the Brisket, is peppered with them. The recession must have ended while I was on the crosstown bus, reflects one character. Adorable was the term Katya used to describe things that were too small for her, be they apartments, diamonds or men.

Philadelphia-based humorist and freelance writer Stacia Freedman has a knack for one-liners and her snappy new novel, Tender is the Brisket, is peppered with them. The recession must have ended while I was on the crosstown bus, reflects one character. Adorable was the term Katya used to describe things that were too small for her, be they apartments, diamonds or men.

The author of numerous feature articles and essays, Friedman has tried her hand at writing for film and television and pursued graduate studies in screenwriting. In Tender is the Brisket, as well as her earlier book, Nothing Toulouse, she hones in on women writers who are, in her description, “on their way up, down and sideways.” Lilith Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough recently caught up with her and her witty aperçus on topics as diverse as Jane Austen, Nora Ephron and The Lucy Show.

YZM: How did you made the leap from nonfiction to fiction?

SF: I actually started out as an aspiring TV and film comedy writer without any serious literary ambitions. I didn’t want to be Jane Austen. I wanted to be Nora Ephron. After five years in the “biz” in LA, I returned east and started taking freelance writing gigs. I wrote humor pieces for newspapers, features for magazines, anything that paid the bills. But I never gave up The Dream. I kept churning out comedic screenplays, plays and eventually novels. After all these years, it’s gratifying to discover that there is an appreciative audience for my style of social satire. And if one of my novels were to be adapted to TV or film? That would be fine!

- 4 Comments

July 1, 2014 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Golden Words: Q&A With Author, Editor, Activist Nora Gold

Nora Gold (source: NoraGold.com)

Nora Gold’s recently published Fields of Exile, a pathbreaking novel about anti-Israelism in academe, was picked by The Forward as one of “The 5 Jewish Books to Read in 2014,” and has received enthusiastic praise from many quarters.

But this is not the first time Gold has received acclaim for her work; Marrow and Other Stories won a Canadian Jewish Book Award, and was praised by Alice Munro. And Gold’s story, Yosepha, appeared in the spring 1985 issue of Lilith.

Gold is also the creator and editor of the online literary journal Jewish Fiction.net, a blogger for “The Jewish Thinker” at Haaretz, and Writer in Residence and an Associate Scholar at the Centre for Women’s Studies in Education at OISE/University of Toronto. She and Lilith’s fiction editor Yona Zeldis McDonough discussed the role ideas play in the creation of a novel, the meaning Zionism continues to have in the Diaspora and the siren song of the short story.

- 1 Comment

June 12, 2014 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Author Q & A: The Many Faces of Sonia Taitz

Essayist, playwright, author of a well-received book on mothering and winner of the Lord Bullock Prize for Fiction, Sonia Taitz is nothing if not nimble as a writer. Although she trained as a lawyer—at Yale no less—the pursuit of a legal career held little appeal for her and she soon returned to her first loves, reading and writing. Mothering Heights: Reclaiming Parenthood from the Experts, is both political satire and heartfelt memoir about the changing role of mothers. The Watchmaker’s Daughter is another sort of memoir, detailing her “binocular” life as the American child of European, Yiddish-speaking concentration camp survivors. Taitz’s novels include In the King’s Arms, a coming-of-age story that has been called a cross between Evelyn Waugh and Philip Roth. And in her forthcoming novel Down Under she takes on Mel Gibson, reinventing the famously anti-Semitic movie star’s past to include an early, pre-fame romance with a Jewish girl. Fiction editor Yona Zeldis McDonough asks Taitz some questions about her wide-ranging literary output and the scarred but heroic parents who shaped her life.

Sonia Taitz (courtesy author)

YZM: What inspired you to make the leap from lawyer to writer?

My adventures in law originated in the mind of my father. A Holocaust survivor whose own education had stopped at age 13, he was determined that I have a careerwhich put me in “a place of importance” in society. He felt that with a law degree I would be armed—at least verbally—if danger reared its head again. Somehow, he equated me with Queen Esther—able to eloquently step into the corridors of power and avert imminent disaster. Because I was good in school (in my case, yeshiva through 12th grade), and because the Torah we analyzed prepared me well for verbal debate, I thought my father’s vision suited me.

But from the time I started college, more creative instincts began to take me over. I didn’t want to win arguments or massage facts; I wanted to weave spells with words, to compose in utter freedom. I didn’t want to be cunningly adversarial, but creative and connective. It didn’t hurt that my mother was a concert pianist (providing Chopin’s Fantasie Impromptu as theme song to my childhood) or that my father wrote poetry in Dachau. Transcendence was as much my legacy as Talmud, or torts.

- 1 Comment

Please wait...

Please wait...