by Yona Zeldis McDonough

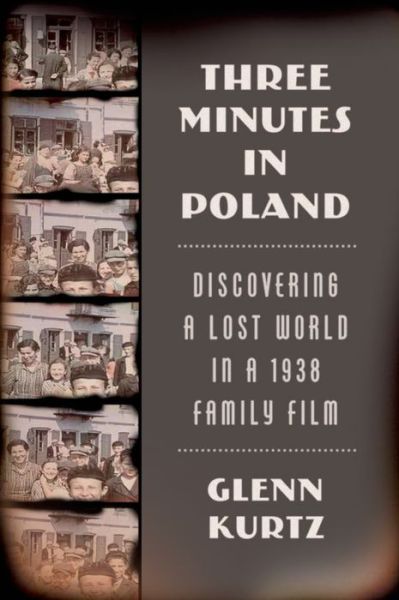

Three Minutes in Poland

When Glenn Kurtz happened upon an old family film in a closet of his parents’ home in Florida, he was intrigued. The film was shot by his grandfather, David Kurtz, during a trip he and his wife made to Europe in 1938—right on the eve of destruction. Kurtz’s initial interest grew into an almost spiritual quest, one in which he was determined to piece together as much as he could about the Polish town of Nasielsk—and the people who inhabited it. The result is the sweeping account in his book, Three Minutes in Poland, both a reverent attempt to document a lost history and a fervent desire to animate it once more. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough chatted with Kurtz by e-mail.

When Glenn Kurtz happened upon an old family film in a closet of his parents’ home in Florida, he was intrigued. The film was shot by his grandfather, David Kurtz, during a trip he and his wife made to Europe in 1938—right on the eve of destruction. Kurtz’s initial interest grew into an almost spiritual quest, one in which he was determined to piece together as much as he could about the Polish town of Nasielsk—and the people who inhabited it. The result is the sweeping account in his book, Three Minutes in Poland, both a reverent attempt to document a lost history and a fervent desire to animate it once more. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough chatted with Kurtz by e-mail.

YZM: How did you research this process of historical reconstruction?

GK: I worked on the book for more than 4 years, though in some sense, the research continues to this day. The images preserved in a photograph or in a film are preserved in a very peculiar way. They are both extraordinarily specific (individual people in a particular place at a specific moment), and at the same time utterly enigmatic. If you don’t already know what or who you’re looking at, the information in the image immediately becomes general, unspecific, and almost mythological (or in the case of old photos and films, nostalgic). Instead of seeing, say, “Chaim Nusen Zwajghaft, gravestone carver in Nasielsk in August 1938,” we see “prewar Polish Jews.” The general description is not inaccurate. But it does not convey information on the same scale as the image itself. It makes the image less specific.

When I first discovered my grandfather’s 1938 home movie, I knew almost nothing about it. I didn’t even know the town in Poland that appears in the film. The great difficulty, then, was to unlock the information contained within the images.

For two years, I searched in archives, in genealogy forums, in old newspapers… everywhere I could think of to find information that might help me identify the individual people in my grandfather’s film—those people who just happened to be in that place at that time when my grandfather tripped the shutter.

I amassed an enormous amount of documentation. But there was no way to link the names in the documents with the faces in the film. I was two years into my search when I received an e-mail that finally enabled me to make this link. A woman in Detroit saw my grandfather’s film online and recognized her grandfather as one of the kids jostling for attention when my grandfather began filming. He just celebrated his 90th birthday, and he was able identify people in the film and help me bridge the distance between documents and images.

Ultimately, I met seven survivors and numerous family members, and from the stories, photographs, letters, and fragments of memory that they retained, I was able to piece together a narrative on the same scale as the film, about individual people in a particular place at a specific moment.

YZM: What about your grandmother, Liza Kurtz?

GK: My grandmother Liza was a force of nature! She was a powerfully willful, determined, and charismatic woman, though by the time I knew her (or was old enough to understand these things), she was in her 80s and very diminished. She arrived in the U.S. in the 1890s with her family, one of 8 children (seven sisters and a brother). Their father was a tailor and never became particularly successful. Yet even in pictures of my grandmother when she was still a teenager, you can see that she was determined to make something of herself. She and my grandfather became quite successful when they were still in their twenties. By the 1930s, they embarked on a series of vacations in grand style: to Italy, to France and England, and to both of their birthplaces in Poland. Later in life, if my grandfather did not want to accompany her, she traveled alone. In 1939, she took a train across Canada, boarded a cruise ship, and toured Alaska for several weeks.

But a force of nature is often difficult to live with. She was domineering and perpetually dissatisfied with others; was reserved and cold–even cruel–to my aunt and my mother. I grew up aware that everyone in the family was silently afraid of her.

In the course of writing this book, however, I got to know her in a different way, through watching her in my grandfather’s film, and in photographs and letters. Here, she appears quite different. She has an expression of joy and love and playfulness in these images that she rarely showed when she was older. I think she admired hard work and achievement—or, rather, the hard work of achievement. Once she felt she had achieved all she had hoped for, she became bitter. She also suffered a terrible tragedy in 1963, when her adored eldest child, my uncle Jerry, was killed in a plane crash.

Even in her 90s, when I was in my late teens, she maintained a regal presence and a keen interest in the family and our accomplishments.

YZM: Who are some of the other women whose stories you uncovered?

GK: I was privileged to meet (and get to know better) several extraordinary women in the course of my research. I could never have done this work without the help of my sister, Dana, who is the real genealogist in the family. I relied extensively on her family research, and we collaborated on the most difficult research problems surrounding our grandfather’s film: How to find a survivor in 2012 whose name on a list in 1946 is the only lead we have; how to find the children or grandchildren or nieces and nephews of someone who was killed during the Holocaust.

My aunt Shirley, who just passed away at age 93, was also of extraordinary help to me. At some point in the process, I realized I might end up knowing more about the families and daily life in a small town in Poland than I knew about life in Brooklyn, where my own family is from. So I began to interview Shirley about her childhood and to gather her recollections of her friends and family. She and her first cousin, Bernice, who is now also 93, spent hours with me, talking about my grandparents; about attending the opening performance of Radio City Music Hall in 1932; about having dinner at the Roxy, the Brass Rail, Schrafft’s—all legendary places in Brooklyn in the 1920s and 1930s.

Among the survivors and their families there were numerous extraordinary women, those who had the strength to survive the Holocaust and then create a life for themselves afterward; and those among the second and third generation, who had to grow up with these memories (and, above all, with the silences and absences).

I’ll mention Faiga Tick in particular. Faiga escaped from German-occupied Poland in the fall of 1939, leaving behind her whole family, having literally married the boy next door the night before she fled, because her father would not allow her to flee as an unattached woman. Faiga and her new husband crossed into Soviet-occupied Poland, and were then deported to Siberia by Stalin in June 1940. She survived the war in a work camp; had a child there; and after the war the family lived in Displaced Persons camps before immigrating to Canada.

When I met Faiga, she was 95 years old. She was a frail, occasionally confused woman, suffering from a slight dementia. But strength can be expressed in many ways. While the names and places and dates in her memories were not always reliable, the mental images of her family in Poland, like those of what she had survived, were stunningly vivid and precise. She remembered the feelings of particular moments, the relations between people, and the way these are expressed in gestures, in phrases, or in a glance. When she spoke about her father, who was a very severe, religious man, or her mother, who ran the family store, she conveyed such force of feeling and such clarity of perception. It was as if these people were still standing in front of her. She made their presence palpable. She understood that her own survival was not just for herself, but that she was a representative of those who had been murdered, and she carried this responsibility with profound passion and grace.

YZM: The film clip that inspired your book—where is it now?

GK: I donated my grandfather’s film to the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in 2009. They undertook the restoration of the badly-deteriorated film (in conjunction with ColorLab Corp., in Maryland), and now the restored version is available online.

YZM: What do you hope people will take away from reading your book?

GK: When my aunt asked my grandmother after the war what had become of her relatives in Poland, my grandmother responded: “They’re all gone.”

I began Three Minutes in Poland consumed by the questions: what is lost when a person (or a community) dies? And what remains after their death? In other words: what is passed on, and what is forgotten?

But the story developed in ways I could never have imagined. To my amazement, my research brought together a community of survivors; of the families of survivors no longer living; and of relatives of those who did not survive. More than 100 people who traced their roots to this town—and, of course, there are many more whom I was unable to locate or contact.

I hope readers will understand that Three Minutes in Poland is about the survival of memory in the face of unimaginable violence and the inevitable losses of time. It is a story of loss; but it is also a story about preservation and reunion.

And I hope that readers will dig out their own family archives, will ask their parents and grandparents about their lives, and will record the answers for future generations.