Author Archives: Yona Zeldis McDonough

October 28, 2015 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

“We Want to Save Lives With This Book”

In 2013 (the most recent year for which full data are available), there were 41,149 suicides reported in the U.S. Someone in this country died by suicide every 12.8 minutes, and suicide was the tenth leading cause of death for Americans. And while there was a slight decline in suicides from 1986 to 2000, over the next 12 years the rate climbed steadily.

In 2013 (the most recent year for which full data are available), there were 41,149 suicides reported in the U.S. Someone in this country died by suicide every 12.8 minutes, and suicide was the tenth leading cause of death for Americans. And while there was a slight decline in suicides from 1986 to 2000, over the next 12 years the rate climbed steadily.

Given these sobering statistics, Shades of Blue: Writers on Depression, Suicide and Feeling Blue, edited by Amy Ferris and just out from Seal Press couldn’t be more timely. The 34 essays represent a wide range of perspectives ranging from writers who reveal their own failed suicide attempts to survivors struggling to make sense—if not peace—with the wreckage left by the suicides of loved ones. Fiction editor Yona Zeldis McDonough asks Ferris about how she came to compile these accounts and what she hopes readers will take away from them.

YZM: What inspired you to assemble this collection?

AF: Robin Williams’s death. Just like most folks, I was in deep, deep sad shock that he had committed suicide, and I felt this urge, this need to do something. I’m a writer. I write. I also had never come out about my very own suicide attempt when I was a young woman. And so I decided to write a post about that, which was doubly inspired by a friend sending me an email, and the subject line read: did you ever try it? I knew exactly what she was asking. So, I sat down and wrote a piece about my greatest failure—my suicide attempt, and it went viral, and folks shared it, and it sort of circled the globe and then I had that ‘aha’ moment—I wanted to put together an entire collection of stories, essays, pieces from other writers, artists, authors, creators who experienced all shades of blue: depression, attempted suicide, family members who had both depression and or attempted suicide, postpartum depression.

YZM: Did you find writers eager or reluctant to talk about their experiences with depression?

- No Comments

October 21, 2015 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

A Novel About How Blogs Have Changed Our Lives

There are approximately over 152 million blogs on the Internet and incredible as it may seem, more blogs are going up all the time. In fact, a new blog is created somewhere in the world every half a second, which, if you do the math, means that 172,800 blogs are added to the Internet every day. So is it any wonder that the art and science of blogging has worked its way into the pages of contemporary literature?

There are approximately over 152 million blogs on the Internet and incredible as it may seem, more blogs are going up all the time. In fact, a new blog is created somewhere in the world every half a second, which, if you do the math, means that 172,800 blogs are added to the Internet every day. So is it any wonder that the art and science of blogging has worked its way into the pages of contemporary literature?

The Good Neighbor (Griffin Books, October 2015), Amy Sue Nathan’s second and latest novel, introduces us to Izzy Lane, Jewish, recently divorced and still reeling from the break-up of her marriage. The newly single mom moves back to the Philadelphia home she grew up in, five-year-old Noah in tow. On a whim, she starts a blog and with the help of her close friends—and her elderly neighbor, Mrs. Feldman—begins to feel like she’s stepping closer to her new normal. Until her ex-husband shows up with his girlfriend. That’s when Izzy invents a boyfriend of her own.

Blogging about her “new guy” provides Izzy with a way to entertain herself Noah’s asleep. After all, what’s the harm, right? But then her blog soars in popularity and she’s given the opportunity to moonlight as an online dating expert. How can she turn it down? Soon everyone want to meet the mysterious “Mac,” someone online suspects Izzy’s a fraud, and a there’s a new, real-life guy who seems pretty interesting. Nathan’s sharp-eyed look at how the blog culture has changed our lives is a smart, stylish read; here’s an excerpt below.

- No Comments

October 20, 2015 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Ethel Rosenberg Reimagined in “The Hours Count”

Although it’s been more than 60 years since Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were executed, their horrifying story still has a powerful hold on the public imagination. As recently as August, 2015, the two sons of the couple wrote an Op-Ed piece in the New York Times that concluded with these words:

Although it’s been more than 60 years since Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were executed, their horrifying story still has a powerful hold on the public imagination. As recently as August, 2015, the two sons of the couple wrote an Op-Ed piece in the New York Times that concluded with these words:

Our mother was not a spy. The government held her life hostage to coerce our father to talk, and when that failed, it extracted false statements to secure her wrongful execution. The apparent rationale for such action—that national security demanded it during a time of international crisis—has disturbing implications in post-9/11 America. It is never too late to correct an egregious injustice. We call on the government to formally exonerate Ethel Rosenberg.

And now there is the publication of The Hours Count, a novel that focuses squarely on the last five years in the life of Ethel Rosenberg. Author Jillian Cantor hewed closely to the facts, but added several fictional characters, including a neighbor, Millie Stein, her Russian husband Ed and her son, David, who at age three is still not talking. Millie is the lens through which we are able to view Ethel in a wholly unexpected way: as wife, mother and friend. Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough talked to Cantor about why she chose to write Ethel’s story and how she was able to blend the factual with the fictional.

YZM: What drew you to the subject of Ethel Rosenberg?

JC: I came across the last letter Ethel (and Julius) wrote to their sons in an anthology of women’s letters that I’d checked out of the library. One of the last things they wrote is for their sons to always remember that their parents were innocent. Before I read this, I hadn’t thought of Ethel as a mother (her sons were six and 10 when she was executed – very similar to the ages of my own sons) or even as potentially innocent. So I did a little research, and I began to believe that she might actually have been innocent. I wanted to reimagine her as a mother, as a woman who was unjustly taken from her family.

- No Comments

October 19, 2015 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

From the Lilith Slush Pile to a Sarah Silverman Film Deal

Ever since I discovered the work of Amy Koppelman winking up at me from Lilith’s slush pile I’ve kept her on our radar. We published her short fiction a few years ago. She’s a novelist of astonishing depth and power, with a dark and haunting voice that is both lyrical and fearless. The rest of the world seems now to agree, as the film based on her novel I Smile Back, starring—yes—Sarah Silverman in a dramatic role, opens commercially later this month after being received enthusiastically at Sundance.

Ever since I discovered the work of Amy Koppelman winking up at me from Lilith’s slush pile I’ve kept her on our radar. We published her short fiction a few years ago. She’s a novelist of astonishing depth and power, with a dark and haunting voice that is both lyrical and fearless. The rest of the world seems now to agree, as the film based on her novel I Smile Back, starring—yes—Sarah Silverman in a dramatic role, opens commercially later this month after being received enthusiastically at Sundance.

In her new novel, Hesitation Wounds, Koppleman introduces us to Dr. Susanna Seliger, a renowned psychiatrist who specializes in treatment-resistant depression. Skilled and compassionate, Susa is always ready to discuss treatment options, medication, and symptom management but draws the line at engaging with feelings. Her own damaged past is made present by one patient, Jim, whose struggles tear her open, revealing her latent guilt that she could have saved the people she’s lost, especially her adored, cool, talented graffiti-artist brother. Spectacularly original, gorgeously unsettling, Hesitation Wounds is a novel that will sink deep and remain—like a persistent scar or a dangerous glow-in-the-dark memory.

In her new novel, Hesitation Wounds, Koppleman introduces us to Dr. Susanna Seliger, a renowned psychiatrist who specializes in treatment-resistant depression. Skilled and compassionate, Susa is always ready to discuss treatment options, medication, and symptom management but draws the line at engaging with feelings. Her own damaged past is made present by one patient, Jim, whose struggles tear her open, revealing her latent guilt that she could have saved the people she’s lost, especially her adored, cool, talented graffiti-artist brother. Spectacularly original, gorgeously unsettling, Hesitation Wounds is a novel that will sink deep and remain—like a persistent scar or a dangerous glow-in-the-dark memory.

- No Comments

October 12, 2015 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

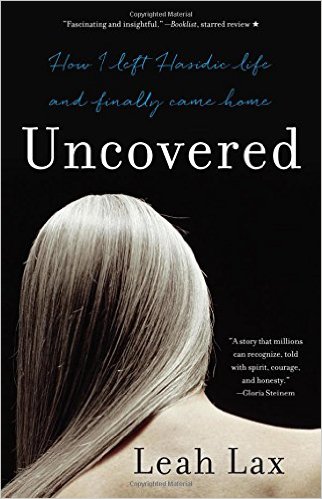

“I Am No Victim”: Leah Lax on Living and Leaving Her Hasidic Life

Leah Lax is familiar to Lilith readers for several of her essays in the magazine, most recently the economically told life history “One Woman’s Resume.” Raised in a Reform Jewish family in Dallas, close to her immigrant grandparents, who still ate schmaltz herring in their elegant nouveau-riche home; she says that growing up, she learned to crochet and ride a horse. In her teens she left this life—and her neglectful parents—to become a Lubavitcher Hasid, and soon after entered into an arranged marriage. Like the others in her community, she did not own a television, read secular books, surf the Net or go to movies or restaurants. Then after nearly 30 years—and seven children—she left that cloistered life behind. Her memoir, Uncovered: How I Left Hasidic Life and Finally Came Home, charts the years she gave over to strict observance of religious law, from hair covering to the order of putting on one’s shoe in the morning, from compulsive pre-Passover cleaning to relinquishing all questioning. It also reveals the secrets she harbored behind the observant façade, and the sprouting of a feminist consciousness as she came to know herself. She talks to fiction editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about her life beneath the wig—and what it was like to emerge from it, uncovered, after so long.

Leah Lax is familiar to Lilith readers for several of her essays in the magazine, most recently the economically told life history “One Woman’s Resume.” Raised in a Reform Jewish family in Dallas, close to her immigrant grandparents, who still ate schmaltz herring in their elegant nouveau-riche home; she says that growing up, she learned to crochet and ride a horse. In her teens she left this life—and her neglectful parents—to become a Lubavitcher Hasid, and soon after entered into an arranged marriage. Like the others in her community, she did not own a television, read secular books, surf the Net or go to movies or restaurants. Then after nearly 30 years—and seven children—she left that cloistered life behind. Her memoir, Uncovered: How I Left Hasidic Life and Finally Came Home, charts the years she gave over to strict observance of religious law, from hair covering to the order of putting on one’s shoe in the morning, from compulsive pre-Passover cleaning to relinquishing all questioning. It also reveals the secrets she harbored behind the observant façade, and the sprouting of a feminist consciousness as she came to know herself. She talks to fiction editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about her life beneath the wig—and what it was like to emerge from it, uncovered, after so long.

YZM: What drew you initially to Hasidic life?

LL: At first: their raw wordless melodies, the mysteries they said were hovering between the lines of our incredible texts, and the intimation that somehow this is me, too, since I was born a Jew, so that it seemed they were offering new self-discovery. I was 16—I think that alone explains a lot.

Then came Hasidic offers of the sublime, and assertions that they owned a huge Truth so old and vast it shut my small mouth, coupled with my weak will and my need to please.

If I dig, I always see more: the homoerotic quality of Hasidic life, and their promise that, if I followed the rules, I’d always feel I belonged, something I had always craved.

YZM: Was Hasidic life sustaining for a time?

LL: It was. I was barely 17 when I left my family, and received no subsequent financial support from them. Of course, I went straight to university on full scholarship and could have simply immersed myself there and grown up for a few years, but still, the Lubavitchers I had met gave me a sense of family, adult concern for my young life, structure, someone other than my damaged family to identify with, a place to go on weekends. They meant a lot.

- No Comments

September 24, 2015 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Jewish Thrifting

I’m on high alert even before I walk through the door, fully charged and primed for action. For the next couple of hours, I will ignore phone calls, texts and emails, morphing into the Bionic Woman, with no need to sit, eat, drink or use the restroom. I am about to embark on what for me is a quasi-scared endeavor: pawing through the schmattes in the National Council of Jewish Women’s thrift shop on East 84th Street in NYC. I love thrift shops of all denominations, but as a Jewish woman, I derive a certain extra bit of nachas from the thrift shops run, and frequented by and most essential of all, donated to by my foremothers, the women of my tribe.

I make these visits with some regularity and with the exception of socks, pantyhose and underwear, depend on them to purchase all of my clothing. I buy nothing new. Why should I? Sadie, Mollie, Esther and Bunny and their pals have already provided me with everything I ever wanted—and more. A long, black cashmere coat from Saks, an Ungaro jacket in maroon quilted velvet, a heavily encrusted purple silk skirt, all beading and sequins, from Ralph Lauren—these are only a few of my thrift shop finds.

There are practical reasons to switch to thrifting: it’s economical and allows me to afford clothes that I would otherwise only dream of. And I believe we have an almost moral imperative to buy secondhand: there is too much stuff in the world and we have an obligation to reuse it.

But even without these incentives, I would still be a Second Hand Rose, for reasons that are less quantifiable but every bit—at least to me—compelling. I feel strange kind of tenderness and pity for all the abandoned and discarded garments, and am endlessly curious about their former owners. Who bought those wide black pants trimmed in feathers and where did she go in them? That pleated navy jumpsuit with the gold trim? The powder blue suede miniskirt? Each has a story to tell and oh, what a story it must be. In my imagining those stories, it’s as if I have been able to resurrect not just the garments, but the women who wore them.

I should add here that I come from a venerable line of thrifters. My mother had the bug, and so did my grandmother, Tania. Well into her eighties, Tania worked as a volunteer at the thrift shop of a Jewish charity in Miami when Collins Avenue and Lincoln Road were still the province of elderly, Ashkenazi Jews who traded the harsh winters of the north and east—in my grandmother’s case, it had been Detroit—for the sunny climes of Southern Florida. My grandmother traveled an hour by bus to get to this thrift shop, and she was given advance pick of the donated merchandise, which is how I came to own the exquisite silk scarf with the lush pink and coral flowers splattered all over it. The name Hermès meant nothing to Tania, but she had a keen eye and the heavy silk, glorious pattern, and hand rolled edges spoke to her of quality. “I thought you would like it,” she said. “And if you didn’t, that was okay too—it only cost $2.50.”

But to get back to the National Council thrift shop, its cousin, the Chai Thrift in Brooklyn, and that wonderful synagogue thrift shop on Long Island, whose name and town elude me now, though I can still tell you what I found there. Here are my roots, here are my people. The ladies, like my grandmother, may now be gone. But what they gathered and cherished, their cunningly styled evening bags, fur coats, palazzo pants and cocktail dresses, represent a group portrait, a patient construction of self that continues to live on, at least for those of us with the eyes to discern it.

- No Comments

July 14, 2015 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

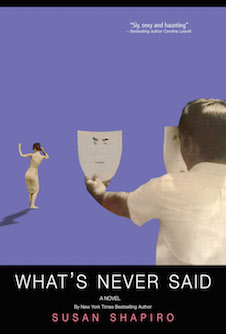

Susan Shapiro: “A Jewish Man Who’s Never Been Married is Schlepping a Different Kind of Luggage Around”

Just as the topic of professor/student relationships is heating up (Harvard and other universities are now banning such liaisons), novelist, essayist and humor writer Susan Shapiro offers her own take on the highly charged subject in her captivating new novel, What’s Never Said. Lila Penn, a naïve, fatherless young woman from Wisconsin, comes to the big city to study poetry and falls, head-first, for Daniel Wildman, her distinguished professor, who also happens to be twenty years her senior. Decades after their tangled involvement ends, she arranges a meeting in downtown Manhattan. But the shocking encounter blindsides Lila, causing her to question her memory—and her sanity. Moving back and forth between Greenwich Village, Vermont, and Tel Aviv, Shapiro slowly unravels the painful history that has haunted both Daniel and Lila for thirty years. In the excerpt below, Lila’s mother encounters her daughter’s new love interest for the first time.

Just as the topic of professor/student relationships is heating up (Harvard and other universities are now banning such liaisons), novelist, essayist and humor writer Susan Shapiro offers her own take on the highly charged subject in her captivating new novel, What’s Never Said. Lila Penn, a naïve, fatherless young woman from Wisconsin, comes to the big city to study poetry and falls, head-first, for Daniel Wildman, her distinguished professor, who also happens to be twenty years her senior. Decades after their tangled involvement ends, she arranges a meeting in downtown Manhattan. But the shocking encounter blindsides Lila, causing her to question her memory—and her sanity. Moving back and forth between Greenwich Village, Vermont, and Tel Aviv, Shapiro slowly unravels the painful history that has haunted both Daniel and Lila for thirty years. In the excerpt below, Lila’s mother encounters her daughter’s new love interest for the first time.

- No Comments

June 25, 2015 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

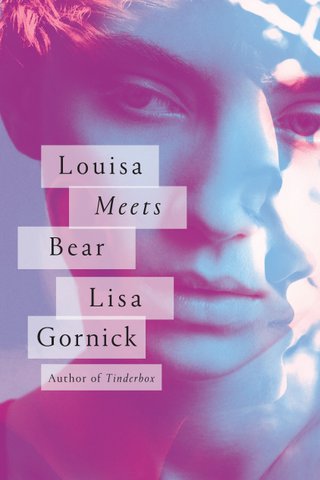

Young Love…and Its Aftermath

Girl meets boy. Girl gets boy. Girl loses boy. But girl and boy do not forget each other. It is the elusive and often surprising nature of their ongoing connection that forms the backbone of Lisa Gornick’s highly acclaimed new collection of interrelated stories, Louisa Meets Bear (Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, $26). Gornick, who is also a psychotherapist, is interested not only in the way things seem on the surface, but also with unseen forces that exert such powerful control over the lives of her characters. Here she chats via e-mail with Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about the assault on the novel, and why the categories for fiction matter so much less than their content.

Girl meets boy. Girl gets boy. Girl loses boy. But girl and boy do not forget each other. It is the elusive and often surprising nature of their ongoing connection that forms the backbone of Lisa Gornick’s highly acclaimed new collection of interrelated stories, Louisa Meets Bear (Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, $26). Gornick, who is also a psychotherapist, is interested not only in the way things seem on the surface, but also with unseen forces that exert such powerful control over the lives of her characters. Here she chats via e-mail with Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about the assault on the novel, and why the categories for fiction matter so much less than their content.

YZM: Let’s talk about the origin and structure of these stories. Did you know from the outset that they would be linked? Or did the connections reveal themselves more slowly, as you were writing?

LG: These stories were written over the past twenty-five years, all as individual pieces intended to stand alone. Originally, there were two sets, each made up of two stories that shared characters. When I first reread the stories with the thought of putting them together into a collection, it seemed, however, that they were all connected on a deeper level—as though the characters could or should have known one another. I went back and rewrote the stories, changing what might have been five degrees of separation between characters to one degree, making timelines to map the events into a single chronology and a larger narrative. With the stories connected now, we follow characters over nearly five decades. The opening story begins in 1961 with a woman’s yearning to have work of her own, and the final story, set in 2009, while about an incident between a mother—the niece of the woman in the opening story—and a son, has as its backdrop the accommodations this mother has made to have work and love in her life.

YZM: You depict a number of absent/dead/damaged mothers here; comments?

LG: It is not an easy road for a woman who wants mature romantic love, a deep hands-on relationship with her children, and meaningful work. There are difficult choices and often irresolvable conflicts between these domains. In Louisa Meets Bear, there are mothers whose lives are marked by tragedy and then, in the next generation, daughters who have begun to find a way.

- No Comments

April 23, 2015 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

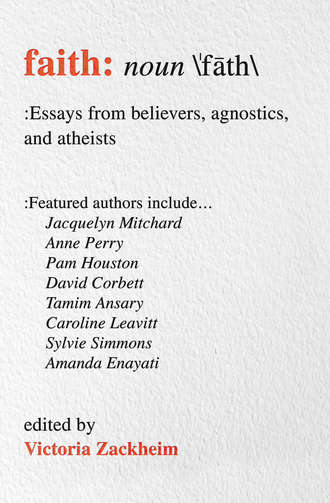

Who Believes and Who Doesn’t?

What do you believe? Why? Is faith a certainty, fixed and immutable, or is it an ongoing process, and evolution of the spirit and the soul? Who has faith and how did she get it? These are just some of the questions that began to tug at Victoria Zackheim, novelist, playwright, screenwriter and editor of five previous essay collections. As she mulled over these thoughts, an anthology began brewing. The resulting volume, Faith: Essays from Believers, Agnostics, and Atheists, showcases the work of 24 writers, including Caroline Leavitt, Aviva Layton, Benita Garvin among others, who have widely divergent views on the subject. Zackheim chatted via email with Lilith Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about the winding road she took in assembling this, her sixth collection, and also about some of the revelations she experienced along the way.

YZM: How did you come to compile this book?

VZ: I’m not sure if there was one event—perhaps it was the composite of several—that led me along this path. What I can say is this: once the journey began, there was no turning back. The early stirrings came from questioning myself about my own faith, a curiosity to clarify what I believed. The deeper I probed, the more I needed to pose questions to friends, until I found myself engaging them in long, soul-searching conversations. Finally, the awareness that I absolutely had to explore the subject of faith and the role it plays (or doesn’t play) in my life led me to the genre that has become so prevalent in my teaching and writing: the personal essay…and then the anthology. Once that was decided, and my agent gave the thumbs-up, I sent an invitation to twenty-five gifted writers who represented a cross-section of cultures, religions, and lifestyles. I was hoping that perhaps ten would accept my invitation, and then I would continue inviting. Twenty-three accepted and the project was launched. After the proposal was completed and the book was sold to Beyond Words, essays began to arrive, I was fascinated to discover that people I was certain were atheists were believers, and a few I assumed to be believers were not.

- No Comments

April 2, 2015 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

She Was Famous Almost 200 Years Ago—and Still Is!

Carol Ockman

On March 19, 2015, Sarah Bernhardt came to town. Or at least her magnificent, outsized spirit did, channeled by art historian Carol Ockman, who participated in an illuminating conversation with Jens Hoffmann of the Jewish Museum in New York. The conversation was part of an ongoing series in which the subjects of Andy Warhol’s Ten Portraits of Jews of the Twentieth Century (1980) will be “interviewed” by prominent experts. Ockman assumed the persona of Bernhardt (1844-1923), who was arguably the most famous actress of all time; she also sculpted, painted, and generally lived her life on a scale most spectacular. (For more about the Divine Sarah B., see “When She was Good, She was Very, Very Good and When She was Bad, She was … Jewish.”) Using slides to augment her remarks, Ockman spoke from the inside out about fame, film, a woman’s role and Jewish identity. Later, Lilith Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough asked Ockman about her long history with the fabled diva.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...