Author Archives: Rabbi Dianne Cohler-Esses

March 1, 2018 by Rabbi Dianne Cohler-Esses

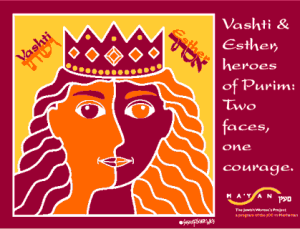

Saying “No” and Saying “Yes”: Feminist Models of Change in the Book of Esther

The last place most feminists would look for a map for transformation is the Bible. But open the Book of Esther, traditionally read by Jews on the carnivalesque holiday of Purim, and we find two contradictory models of social change.

The last place most feminists would look for a map for transformation is the Bible. But open the Book of Esther, traditionally read by Jews on the carnivalesque holiday of Purim, and we find two contradictory models of social change.

The story turns on the unusual heroics of two women. Indeed, the overall narrative structure is characterized by twos: a hero and a villain: Mordechai and Haman; two queens: Vashti and Esther; and two words: a “no” and a “yes” (I could go on). Both women risk their lives. Vashti has the unimaginable courage to say “no,” refusing to enter the king’s chambers; Esther has the courage to say “yes,” daring to enter the king’s chambers unsummoned, ultimately saving her people by doing so.

The story begins with Vashti. King Ahasuerus, Vashti’s gluttonous drunkard husband, demands she appear before his all-male party of guests “to show the peoples and the princes her beauty; for she was good looking” (Esther 1:11). But “Vashti refuses the King’s command” (Esther 1:12).

We are not told why she refuses. But we can certainly imagine. Perhaps, the royal queen didn’t like being ordered around, or, she didn’t want to be shown off as if she was a piece of furniture, or she simply didn’t like living with her foolish husband and knew refusing him publicly would be her ticket out of the palace.

As it turns out, her radical refusal was threatening, not only to the king but apparently also to every man in the entire kingdom.

- 4 Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...