Author Archives: Maya Bernstein

April 21, 2011 by Maya Bernstein

Commemorating

It was one week into my family’s trip to Israel, and we lost our camera. Perhaps it was stolen. Most likely it fell out of the bottom of the stroller, while I was digging for sunscreen, or pretzels, or a hat. Perhaps it was the inevitable sacrifice, to appease the gods who watch over those who travel with young children and worry about losing BPA-free bottles and spoons, favorite dolls’ clothing, socks, diaper-bags, not to mention, of course, the children themselves. I noticed the camera was gone when the children were bathed and clean and dressed for the Sabbath. The girls had flower head-bands in their hair and the baby was wearing a vest, the sun was setting over the walls of the old city in Jerusalem, and the air smelled of the exhaust fumes of the last Friday buses, and of jasmine.

It was one week into my family’s trip to Israel, and we lost our camera. Perhaps it was stolen. Most likely it fell out of the bottom of the stroller, while I was digging for sunscreen, or pretzels, or a hat. Perhaps it was the inevitable sacrifice, to appease the gods who watch over those who travel with young children and worry about losing BPA-free bottles and spoons, favorite dolls’ clothing, socks, diaper-bags, not to mention, of course, the children themselves. I noticed the camera was gone when the children were bathed and clean and dressed for the Sabbath. The girls had flower head-bands in their hair and the baby was wearing a vest, the sun was setting over the walls of the old city in Jerusalem, and the air smelled of the exhaust fumes of the last Friday buses, and of jasmine.

What upset me most was losing a week’s worth of pictures. My oldest moaned: “now it’s like we were never here.” I momentarily entertained the thought of buying a new camera, and retracing our steps. My husband suggested that we could leave pages of our photo-album blank; a trip of blind images, wisps of memories trickling ephemeral from between our fingers.

Now, though, that it is Passover, and the leavened excesses of our existence have been burned, for the moment, and, as a people, we are immersed in the preservation of an ancient psychic memory, the loss seems strangely appropriate. It has reminded me to spend some time experiencing, rather than preserving an experience. I have become so accustomed to reflecting while living, that, perhaps, I have cheated myself out of the full joy of being, of living, without trying to figure out how to package, market, preserve that life. My camera, Twitter account, Facebook site, all at once seem like chametz, bloated with self, replete with very me. How appropriate to be without a camera on Passover, to travel, suddenly, lighter, with a different lens. Emptying myself of these vehicles for expression, I find more space to be. I am reminded of a poem by Sir Thomas Browne: (more…)

- 7 Comments

March 1, 2011 by Maya Bernstein

Witch

When my grandmother babysat for us when I was young, we always played “Witch.” This was a glorified version of Hide and Seek, in which the witch hunted for the innocent children with the hope of capturing and cooking them in her cauldron for supper. My grandmother was the witch, of course, since, hands down, she had the best cackle, and since she had invented the game. We hid (I remember the soft feel of the velour on the back of the chair in the corner of my parent’s bedroom), and she walked around the hallways, cackling and talking in her witch voice, threatening to find us. I don’t remember if she actually found us, or if we simply emerged, terrified, but she appeased us with pots of spaghetti and slices of mozzarella cheese. She’d sing us to sleep in her low alto, and laugh that she was a terrible babysitter, and that we weren’t allowed to repeat anything she said to our parents.

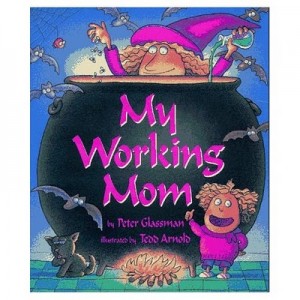

Memories of playing Witch with my grandmother came flooding back at me when I opened last week’s New Yorker magazine to Tina Fey’s article about the challenges of being a working mother. Fey’s daughter comes home from preschool one day with a book with a witch on the cover called “My Working Mom.” Though her daughter is pre-literate, Fey reads into this – my mother the witch who voluntarily goes to work – unleashing her relentless, unforgiving internal debate about whether or not she should take a break from her thriving career to have a second baby. On the one hand, she argues: “And what’s so great about work, anyway? Work won’t visit you when you’re old. Work won’t drive you to the radiologist’s for a mammogram and take you out afterward for soup.” On the other, in addition to the fact that many people depend on her for their jobs, she is also breaking through glass ceilings in comedy, an industry still dominated by (sexist) men, which is why, she writes, “I can’t possibly take time off for a second baby, unless I do, in which case that is nobody’s business and I’ll never regret it for a moment unless it ruins my life.” (more…)

Memories of playing Witch with my grandmother came flooding back at me when I opened last week’s New Yorker magazine to Tina Fey’s article about the challenges of being a working mother. Fey’s daughter comes home from preschool one day with a book with a witch on the cover called “My Working Mom.” Though her daughter is pre-literate, Fey reads into this – my mother the witch who voluntarily goes to work – unleashing her relentless, unforgiving internal debate about whether or not she should take a break from her thriving career to have a second baby. On the one hand, she argues: “And what’s so great about work, anyway? Work won’t visit you when you’re old. Work won’t drive you to the radiologist’s for a mammogram and take you out afterward for soup.” On the other, in addition to the fact that many people depend on her for their jobs, she is also breaking through glass ceilings in comedy, an industry still dominated by (sexist) men, which is why, she writes, “I can’t possibly take time off for a second baby, unless I do, in which case that is nobody’s business and I’ll never regret it for a moment unless it ruins my life.” (more…)

- No Comments

January 3, 2011 by Maya Bernstein

Puppy Love

I’ve fallen for a dog named Duncan. He is the new love of my life. He has long black hair, and is the size of a large boot. He’s not a smiley dog – he’s quite serious, but can you expect anything else from a working dog? He makes good money, too. And he seems to have a strange habit of not walking upstairs, but being carried, while caressed, sweet nothings (in the form of the word “seek”) being whispered in his ear. I think I can handle that.

I’ve fallen for a dog named Duncan. He is the new love of my life. He has long black hair, and is the size of a large boot. He’s not a smiley dog – he’s quite serious, but can you expect anything else from a working dog? He makes good money, too. And he seems to have a strange habit of not walking upstairs, but being carried, while caressed, sweet nothings (in the form of the word “seek”) being whispered in his ear. I think I can handle that.

But – I get ahead of myself. Let us begin at the beginning.

My daughter woke up one day last week with a number of suspicious red dots on her legs. She complained that they itched. When, after three days, they seemed to increase in number, we took her to the doctor. Here’s where it gets exciting – ready? The doctor said that it didn’t look like spider-bites (spiders, I learned a couple of days later, are wonderful critters to have in your house); it didn’t look like scabies; and – here’s the clincher – it’s possible they could be bed bug bites. (more…)

- 2 Comments

November 4, 2010 by Maya Bernstein

Nuts

I was playing in the kitchen. The frying pan was hot with olive oil, and the onions were browning. I had already cut up the garlic, brown shitake mushrooms, and brussel-sprouts. I was boiling sweet potatoes on another burner, and red quinoa on yet another. I spiced the onions with some salt, black pepper, and thyme. The Chieftains were crooning from the stained c.d. player, the one we have to rig up to our kitchen scissors when we want to listen to the radio, the baby was sleeping upstairs, and the older kids were in school. I had a swim to look forward to later in the day, and all was well in the world. I added the veggies to the onions, cut the sweet potatoes in cubes, added them, and then mixed in the quinoa. It looked beautiful, and smelled delicious. I could have stopped there. But in a moment of inspiration, I decided the dish needed chopped toasted pecans to be complete. I looked around me. Coast was clear. I tiptoed toward a far cabinet, stood on a stool to reach the highest shelf, and stretched long. Hidden in a dark corner were bags of nuts. Walnuts, pecans, almonds, pine nuts, cashews. Previous cooking staples in my mostly vegetarian diet. I took a deep breath, and, terribly, irresponsibly, immaturely, sprinkled the dish I knew my two year old wouldn’t touch anyway with the forbidden fruit. (more…)

- 3 Comments

September 7, 2010 by Maya Bernstein

Return

It is a time of returning. Rosh HaShanah, the Jewish New Year, is upon us. We are in the midst of the Hebrew month of Elul, which, in preparation for the Days of Awe, is a period of Teshuva, often translated as repentance, but which literally means to go back, to return. PJ Library sent us a book called Engineer Ari and the Rosh HaShanah Ride, about a man who turns his train around and returns to his friends. Jews around the world are involved in spiritual preparation, returning to God, returning to the selves they wish to be. So, I feel, it is an especially fitting time for me to return.

Except that I’m returning to work.

In preparation for the auspicious day, I’ve been maniacally going through drawers and scrubbing under sinks. We had to rearrange our house to make room for the new baby, and I’ve been uncovering every crevice in an attempt to find more space. Unlike the mother hummingbird, who spent less and less time on her nest before her babies flew off, I have become obsessed, spending hours going through bookshelves and re-arranging the angles of chairs before I fly off. I am trying to leave my mark, so that when I’m no longer home when the baby cries, turning his head from side to side in his crib, searching for me, he will know that I love him, because he has a dresser now, and a cubby at the bottom of the crowded closet, and a quilt hanging on the wall. Maybe I’ve been trying to make the new seem old, and comfortable, before the old routine returns, belying its name, and bringing more change.

It’s a strange business, this “returning” to one’s self. Pregnancy and childbirth are especially powerful physical metaphors for the reality that we are always in flux. My grandfather used to say that change is the only constant. In the past months, I have watched my body wax and wane like the moon. I have cut dozens of white crescent fingernails, surprised at how quickly they grow. I have built sandcastles by the side of a lake, and thought of nothing else but how much more water we need for the moats, and how sweet it is that children of a certain age don’t walk, but run, no matter how small the distance. And my ears are full of the sweet sighs and grunts of a new life. I have been present in my motherhood, having nothing else tugging at my attention. I return now to a life conflicted. I will have to go through my internal drawers and closets and create more space. Perhaps I will uncover a moonlit stream of space for spirit and self and soul. For God to leak in and help me to be present. And remind me to leave some drawers unoccupied, some walls blank, some space between my ribs to breathe.

- No Comments

July 21, 2010 by Maya Bernstein

A Room of One’s Own, In Time

There was a great cartoon in the New Yorker magazine a couple of weeks ago; it pictures a mother driving with her three kids in the back seat. The kids were hollering, fighting, and, one could safely assume, had very sticky fingers. The mother’s eyes were narrow slits in the rear-view mirror. The bumper sticker or the back of the car reads: I’d rather be working.

Over the past six weeks, during which I have been home with my newborn and two young children, one of whom is being toilet trained, I admit to hatching numerous plans to escape to my quiet office and its spacious rooms, far from the unquenchable, insatiable mouths of babes. But now, as the midpoint of my maternity leave is incomprehensibly already behind me, I contemplate returning to work with apprehension. Is it possible that this period of time is almost over? That to these days which fold over each other and melt together, clouded in the haze of interrupted sleep, will be added the extra responsibility of functioning in the work world? (more…)

- 1 Comment

July 6, 2010 by Maya Bernstein

She’s A Boy

A month ago, a day after our son was born, my husband brought our “big girls,” ages 4 and 2, to visit me and the newborn in the hospital. “You have a baby brother!” I said to them. The big one, already old enough to know that boys have cooties, lamented the fact that it wasn’t a baby sister. The little one peered into his glass hospital basinet. “She’s a boy?” she asked.

Over the course of the past few weeks, I’ve been surprised at the reactions, including my own, to the fact that a male child was born into our family. I have been overwhelmed by the rituals and practices that surround the birth of a baby boy. I gave birth on a Wednesday, and came home on a Friday afternoon, exhausted, and ready to cocoon. That very night, though, while I nursed upstairs, our living and dining rooms were filled with guests; well-wishers who came to sing, tell stories, give blessings, and eat chick-peas. This traditional event, called a Shalom Zachor, which takes place on the first Friday night after a male child is born, is an opportunity for the members of the community to come and welcome the new child. It is an event that takes place only for boys; girls are welcomed into the Jewish people immediately by virtue of their birth. But since the boy has not yet been circumcised, he is, supposedly, despondent, and is cheered up only when throngs of people descend upon his exhausted parents’ house.

My husband and I hadn’t even wanted to partake in this ritual, but gentle communal encouragement won us over. And I must admit, that, as I sat upstairs, listening to the familiar voices of friends singing and sharing words of Torah, I felt a surge of, could it be, maternal pride, and had a few private moments of clucking around like a proud chicken; I had produced a male heir. I couldn’t help but feel that all of these people were here to celebrate me, and that I had done something right in giving birth to a boy.

This was reinforced in the wider world as well. When I was leaving the hospital with the bundle in my arms, a woman smiled at me in the elevator. “Is it your first?” she asked. I told her that I had two girls at home. “Well,” she said, “you’ve finally got your boy.” In fact, when I gave birth to our second daughter, the nurses wished me well when I was leaving, and said, “see you next year.” When I raised my eyebrows they smiled – “well, aren’t you going to try for a boy?”

Do we still live in a world in which it matters whether or not you give birth to a boy or a girl? Is there something particularly to be celebrated, in the Jewish community and beyond, when a male child is born? Or is it simply that after having two of “the same,” what is recognized is having something “different?” And what does my moment of clucking maternal pride say about me? Am I simply reacting to communal forces that, despite myself, have affected me? Or am I carrying hidden stereotypes that I have never expressed, even to myself? And how do I navigate that, as a mother?

I’m not sure yet. In the meantime, though, I’m reluctantly introducing male pronouns into my daughters’ vocabularies.

-Maya Bernstein

- 2 Comments

May 10, 2010 by Maya Bernstein

Nesting

In the leafy bushes immediately outside of our front door, a hummingbird has built a nest. For the past three weeks, during which time my husband has grown a beard in mourning for his mother, and I have swollen into the last month of my third pregnancy, the mother hummingbird has been sitting on her two tiny eggs, which recently hatched two Lilliputian, helpless, hummingbird chicks. We’ve been trying not to use our front door, but none of us can long resist the desire to tiptoe past this minuscule miracle, and peer inside.

Our daughters are delighted. They’ve told everyone. “Our hummingbird made a mest,” says my two year old, and the four year old chimes in, “and all day long she sits like this, without moving, keeping her babies warm.” She imitates the bird, staring straight ahead, unblinking, until she turns her big, light-filled eyes to her audience, waiting for them to become infected with her joy. Though the chicks have hatched, still the hummingbird sits, keeping the live little chicks warm, but now she also flits around, gathering whatever it is that nourishes tiny birds, and bringing it in her beak to her ravenous brood. She feeds them and sits on them again.

Often, I find myself hovering near our front door and gazing protectingly outside. If the mother is out foraging, and I notice a crow or robin nearby, I hiss angrily. My own children seem to me like frightening giants when they leave our house, squealing and excited to gaze at what the natural world has laid at their fingertips. “Quietly! Gently! Not too close!” I warn, knowing that I am partly talking about myself, about the turning, stretching new life within me, slowly descending, soon to hatch. I identify with the beady-eyed, resigned, taught expression of the mother hummingbird, an expression which acknowledges with resolve that fragile life is within its care.

Each morning, when my husband returns home from the morning minyan he attends daily to say Kaddish, the mourner’s prayer, he reports on the state of the birds. “She was sitting on the nest,” he shares, or “she must have been out gathering food.” Each day we wonder whether or not they are surviving, and what the next day will bring. In the evening, the children put their hands on my belly. “It’s moving!” they shout as a fist or foot sweeps across my translucent belly. At night, when I toss from one side to another, seeking elusive comfort, my dreams are a-flutter with hummingbird, tranquil and stoic on her nest. Sometimes I dream that I am her chick, curled up beneath her warm, breathing body, and sometimes I dream I am she, and am overwhelmed by a desire to fly far and fast, away, even as I sit.

–Maya Bernstein

- 1 Comment

April 27, 2010 by Maya Bernstein

Anyu

I am back on the train again. Strangely, this morning, it is the window that is foggy, preventing me from seeing clearly the world beyond, rather than the air being full of Bay Area morning fog. Last week, my mother in law passed away unexpectedly. I have just returned from the week of sitting Shiva with my husband and his family. My mother, sister, and her baby flew across the country from New York to be with our daughters. A whirlwind of motion in an attempt to preserve some semblance of stability, in a world that has become so suddenly foggy.

How do you talk to children about death? In the few weeks that their grandmother was very sick, we began to try to prepare our children. “Your Anyu is very sick,” we told them, “and Papa is going to visit her to try and help her feel better.” Our oldest furrowed her brow, and then said: “Papa, don’t get too close – we don’t want you to get sick.”

One beautiful afternoon on Passover, when the weather in Palo Alto seemed a mockery of the cold within us, I was sitting in our garden with the girls, and the little one noticed a bee on the ground. “Look!” she shouted, and we all ran over. The bee was hobbling, on the verge of death. “That bee is very sick,” I told the girls. “It will most probably die soon.” The little one looked closely at the bee. “Bee – sick,” she said slowly, “and Anyu sick.”

When I received the dreaded phone call, I held the girls close, and told them that Anyu had died. The older one tried to explain it to the little one: “When someone dies, it means we never see them again.” And then she asked me: “Did Anyu get old?” Their Anyu was just shy of 62; her own mother is alive, 93 years old, and is in mourning for her daughter. All day long, the older one was trying to work it out. “I’m going to die before my sister, and you’re going to die before Papa, and Papa’s going to die before me…” attempting to comprehend the incomprehensible.

We made pictures and talked about memories and read all of the books and played with all of the toys and wore all of the clothes Anyu had given them. Now that their father has returned, unshaven and watery-eyed, they are slightly wary of him. Their windows, through which they peer bright-eyed and joyous, are clear, like those on the other side of this train; ours are so blurry it seems impossible to imagine clear sight. They cannot comprehend their own loss. They have lost a grandmother, a friend, a confidante, an advocate, a role-model. They have lost one of the finite number of people on this planet who love them more than anything in the world.

They watch us closely as we blink our eyes, and with our damp sleeves try to rub at the windows, hoping the sun will begin to shine through.

–Maya Bernstein

- 2 Comments

March 3, 2010 by Maya Bernstein

Say “Cheese”

Virginia Heffernan, in her piece Framing Childhood in this week’s New York Times Magazine, writes, with only a hint of sarcasm, that “we form families in the Internet age so we can produce, distribute, and display digital photos of ourselves.” I am here to admit, that at least from where I’m sitting, she speaks the truth. From the “marching orders,” which “come immediately, with the newborn photo, [and] must be e-mailed to friends before a baby has left the maternity ward,” the business of parenting is intertwined with the business of photo-taking, sharing, tweeting, Facebooking, and, shouting from the rooftops – look what I’ve done!

I justify the obsession by reminding myself that our closest family members live hundreds of miles away. I am doing a great service, I think, when, in the middle of a game, instead of playing along, I jump up and run for the camera. I am conquering lands and oceans, bringing my children into the homes of the people who love them most.

For ultimately, this obsession with keeping records of our children, and sharing them with anyone who will gaze smilingly along with us, is connected to the overflowing human desire to be in relationship. And, like all of today’s technology, the act of taking a photograph creates the illusion of being in relationship. When we take out our cameras, we think we are saying to our children, our extended families, and our friends: you are important to us. It’s analogous to “friending” someone, or tweeting at someone. What we’re forgetting, though, is that when we pulled the i-phone out of our back pockets, our kids were in the middle of a game, engrossed in real relationship, and we interrupted them, or, worse, extracted ourselves from being in real life relationship with them to duck into the role of observer. We’re engaged, but not too engaged.

Because relationships are hard, and technology is easy. It is harder to be an active member than to be an observer, aloof, behind the camera, manipulating the images, choosing what to show and to whom and when. And parenting is one of the messiest relationships of them all. It is infinitely harder to be a parent than to showcase our children. It is harder to be a good child than to send cute pictures to the grandparents.

My family came to visit this weekend. From the moment they arrived, cameras and camera-phones were clicking, as if, somehow, those ephemeral pauses, cloaked in hugs and smiles, could help bridge the gap of distance, and delay time, keeping us close together a little while longer. Interestingly, the frequency of the prevalence of the cameras diminished over the course of their visit. Eventually, we all got too busy being together. Eating. Going to the park. And laughing, spontaneously, when things happened so fast that we forgot to record them. And when I look back at the time we spent, those fleeting moments which cannot be shared over the internet on Kodak Gallery or Snapfish, are the ones that will stick forever, messy, joyous, and gone, guaranteeing we’ll need to come back for more.

–Maya Bernstein

- 1 Comment

Please wait...

Please wait...