by Maya Bernstein

Witch

When my grandmother babysat for us when I was young, we always played “Witch.” This was a glorified version of Hide and Seek, in which the witch hunted for the innocent children with the hope of capturing and cooking them in her cauldron for supper. My grandmother was the witch, of course, since, hands down, she had the best cackle, and since she had invented the game. We hid (I remember the soft feel of the velour on the back of the chair in the corner of my parent’s bedroom), and she walked around the hallways, cackling and talking in her witch voice, threatening to find us. I don’t remember if she actually found us, or if we simply emerged, terrified, but she appeased us with pots of spaghetti and slices of mozzarella cheese. She’d sing us to sleep in her low alto, and laugh that she was a terrible babysitter, and that we weren’t allowed to repeat anything she said to our parents.

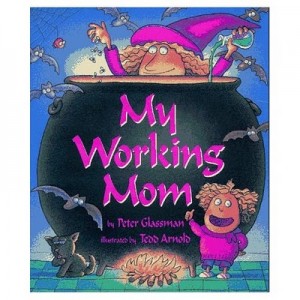

Memories of playing Witch with my grandmother came flooding back at me when I opened last week’s New Yorker magazine to Tina Fey’s article about the challenges of being a working mother. Fey’s daughter comes home from preschool one day with a book with a witch on the cover called “My Working Mom.” Though her daughter is pre-literate, Fey reads into this – my mother the witch who voluntarily goes to work – unleashing her relentless, unforgiving internal debate about whether or not she should take a break from her thriving career to have a second baby. On the one hand, she argues: “And what’s so great about work, anyway? Work won’t visit you when you’re old. Work won’t drive you to the radiologist’s for a mammogram and take you out afterward for soup.” On the other, in addition to the fact that many people depend on her for their jobs, she is also breaking through glass ceilings in comedy, an industry still dominated by (sexist) men, which is why, she writes, “I can’t possibly take time off for a second baby, unless I do, in which case that is nobody’s business and I’ll never regret it for a moment unless it ruins my life.”

Memories of playing Witch with my grandmother came flooding back at me when I opened last week’s New Yorker magazine to Tina Fey’s article about the challenges of being a working mother. Fey’s daughter comes home from preschool one day with a book with a witch on the cover called “My Working Mom.” Though her daughter is pre-literate, Fey reads into this – my mother the witch who voluntarily goes to work – unleashing her relentless, unforgiving internal debate about whether or not she should take a break from her thriving career to have a second baby. On the one hand, she argues: “And what’s so great about work, anyway? Work won’t visit you when you’re old. Work won’t drive you to the radiologist’s for a mammogram and take you out afterward for soup.” On the other, in addition to the fact that many people depend on her for their jobs, she is also breaking through glass ceilings in comedy, an industry still dominated by (sexist) men, which is why, she writes, “I can’t possibly take time off for a second baby, unless I do, in which case that is nobody’s business and I’ll never regret it for a moment unless it ruins my life.”

My grandmother, in an inverse situation from many women today who have no choice but to work, had little choice but to stay at home and raise her children. She didn’t have the luxury of Fey’s anxious indecisions. Her daughters, flush with the feminist revolution, became doctors, marched pretty and proud into boy-club medical schools, and went on to have thriving careers, and children. Ran themselves down, on call at nights, seeing patients all day, juggling schedules, trying to do it all. Some women of my generation are trying to play the clock game. Have a career first, take a break in their mid-30s to start a family (and write a novel), and jump back on the wagon when the kids are in school. Good luck. Or they passionately embrace the one or the other – mother or professional – standing stoically by their decision, and peeking over their shoulders only in the dark, when no one is looking. Or, like me, they play the part-time game, part-time mom, part-time professional, a little of this, a little of that, and not too much of anything.

Fey’s piece reminded me that even the women (perhaps, especially those women) whom we think have it figured out, have fame and fortune, personal fulfillment, and motherhood, are, in fact, insomniacs, trying to think “about anything else” so that they can fall asleep in peace.

But we can’t fall asleep in peace. Because when the babies done crying, and the kitchen done cleaning, and the laundry done folding, and the emails done buzzing for the night, the witches are still cackling. I can hear them now, walking the hallways, laughing and stirring their pots. Shaking their heads at our illusion of choice, at our attempts to continue hiding in the corners of our rooms with the hope that we’ll figure it out. Because we won’t. We’ll do what we must, and, when we have the luxury of making a decision, we’ll perseverate, stuck where women get stuck, choosing between ourselves and others, between what we want to do, and what we think we should do.

And, if we’re blessed to become grandmothers, we’ll throw back our heads, and cackle. And we’ll play Witch with our granddaughters when their mothers are at work. For what is more frightening, more wonderful, and more true, than that loving cackle, threatening to find you and cook you for dinner, when the pot of spaghetti is already on the stove?