Author Archives: Elizabeth Mandel

August 9, 2016 by Elizabeth Mandel

When They Mess Up Your Daughter’s Ice Cream Order

A friend of mine—let’s call her Naomi––was in the local ice-cream store with her six-year-old daughter—Claire, for the purpose of this narrative. Claire, in her polite six-year-old voice, asked the woman behind the counter for chocolate-chip-cookie-dough topping on her cone.

A friend of mine—let’s call her Naomi––was in the local ice-cream store with her six-year-old daughter—Claire, for the purpose of this narrative. Claire, in her polite six-year-old voice, asked the woman behind the counter for chocolate-chip-cookie-dough topping on her cone.

Here’s what happened next.

The server, hearing “chocolate chip,” proceeded to dole out a generous spoonful of chocolate chips on top of the scoop. Naomi turned to Claire. “You wanted chocolate chip cookie dough, honey, not chocolate chips, right?” Claire: “Yes, but it’s OK. Chocolate chips on top are fine.” The server overheard, smiled, apologized for the error, and said she was happy to remake Claire’s cone. The little girl again said it was OK, it didn’t matter, she was fine with chocolate chips. She insisted on eating the cone as it was.

This isn’t a story about ice cream, of course.

- No Comments

January 20, 2014 by Elizabeth Mandel

King & Mandela

The arrival of Martin Luther King Day six weeks after the death of Nelson Mandela naturally invites discussion of equity and equality. At home, with our daughters, we are reinforcing the lessons Dr. King and Mr. Mandela taught the world. In addition to our family discussions, our daughters are fortunate to have a grandmother who met with Mr. Mandela personally. I look forward, as the girls grow older, to them discussing that experience in depth with my mother, Harriet Mandel.

In the meantime, in memory of Mr. Mandela and in honor of MLK Day, I share below my mother’s memories of those meetings:

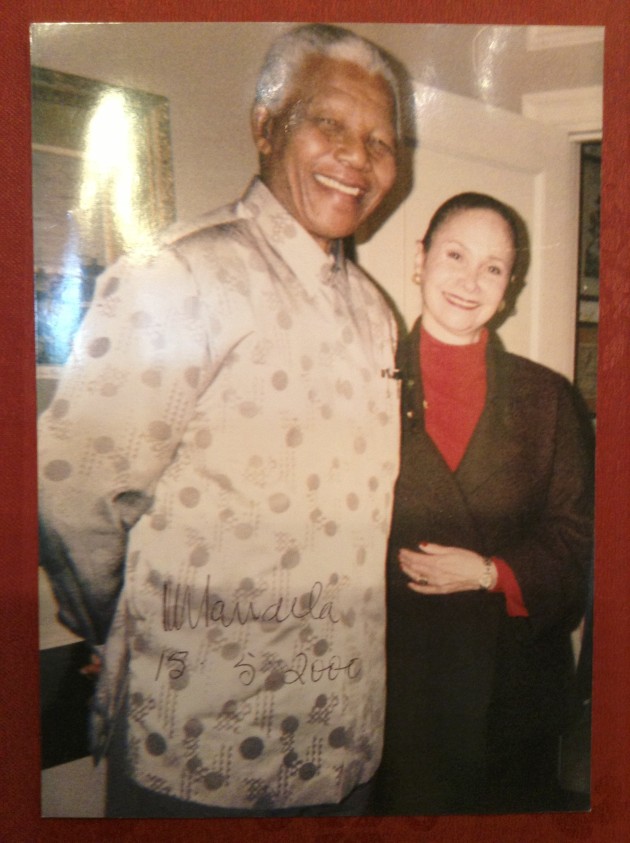

Harriet Mandel and Mr. Mandela

With his dazzling smile and twinkling eyes, radiating warmth, charm, and charisma and dressed in a signature boldly patterned shirt, Nelson Mandela strode into the room for our meeting. It has been 13 years since I had the uncommon privilege of engaging in extended conversations with Mr. Mandela, but the memories remain powerful as ever.

Nelson Mandela’s story made my spirits soar as he led South Africa in its dramatic journey from apartheid to democracy. Along with the rest of the world, I tracked this life lived on the highest planes of human fortitude, endurance and purpose. We longed for the release of this indomitable spirit from prison, and were exhilarated by his example in freedom. Imagine how I felt when an opportunity came for me to meet this luminous hero.

In the year 2000, South African Ambassador to the United States Sheila Sisulu introduced me to Nelson Mandela. Through my career in international diplomacy and Jewish community relations, I had come to know Mrs. Sisulu when she served as South Africa’s Consul General in NYC from 1997-1999. We were guests in each other’s homes (I had the honor of hosting her in ours for Shabbat dinner) and our professional relationship developed into a personal friendship. Mrs. Sisulu was a lifelong activist for educating and empowering the underprivileged, and a civil rights supporter who fought against apartheid. She was also the daughter-in-law of Walter Sisulu who, together with Mr. Mandela, founded the African National Congress’ (ANC) military wing, and served at the same time as Mr. Mandela in Robben Island prison. In 1999, she was personally appointed by Mr. Mandela as the first black person and first woman to represent South Africa as the country’s ambassador to the United States.

In 2000, Mr. Mandela was in the process of establishing the Nelson Mandela Foundation, with the mission of promoting dialogue to resolve global conflicts. He was deeply invested in exploring a resolution to the Arab-Israeli conflict, and planned to come to New York City to speak with “New York Jewry” to garner support for his Middle East peace plan. Mrs. Sisulu asked me to arrange for a meeting between Mr. Mandela and Jewish community members. She also asked that, given the controversial nature of the subject, Mr. Mandela and I meet first for preparatory discussions.

This came against the background of complicated relationships between Mr. Mandela, Israel and the Palestinians. Israel maintained close military ties with apartheid South Africa until the end of the regime. Mr. Mandela, long associated with national liberation causes, was supportive of the Palestinians, and critical of Israeli policy towards them, though he did publicly support Israel’s right to exist. Neither Israel nor the Palestinians gave much support to his plan (which each thought was either to simplistic or too excessive), but Mr. Mandela was determined to make his case, and forged on.

In the first half of 2000, Mrs. Sisulu arranged two extended one-on-one conversations between Mr. Mandela and me, both times in his suite at the Waldorf Astoria. I vividly remember Mr. Mandela walking into the room for the first time. My immediate thought was, here is a prince – which indeed he was. I later learned that he was the son of Chief Henry Mandela of the Madiba clan of the Xhosa-speaking Tembu people. He had relinquished his claim to the chieftainship to become a lawyer. He radiated grace, dignity and energy, yet was surprisingly down to earth. He unhesitatingly embraced me in a warm, welcoming hug and joked that Mandela and Mandel were destined to meet.

It was a rare honor to spend hours talking with this noble man, but it also felt relaxed and comfortable. In fact, it was truly remarkable, and a testament to the greatness of this global hero, that he put me so at ease and that our conversation flowed as if we were long time friends. Mr. Mandela’s charisma was exhilarating, but it was his obvious respect and consideration for the opinions of others – in this case, a stranger’s – that left a lasting impression and underscored his distinctiveness.

We spoke casually for a while, and then turned to the purpose of the meeting. Mr. Mandela noted that he was aware that his sympathetic views towards the Palestinians would probably not find a welcome audience in the Jewish community. However, he wanted to engage this group because he believed that the American Jewish community’s understanding of his peace mission would promote his cause in Israel. He asked that I give him background on and insight into the American Jewish community to help him communicate in resonant ways.

My background is in international affairs, with a specialization in the Middle East, and I had spent my professional life dealing with global leaders on this issue.. But Nelson Mandela was in a league of his own, and I was humbled by my challenge. Rather than express my personal opinion on the complex issue of Israeli-Palestinain relations, I sought to take Mr. Mandela into the “Jewish mind set” and provide insights about the audience he was to address.

Mr. Mandela was as keen listener as he was a speaker, and showed genuine interest in an even exchange. To my mind, this open give-and-take was a measure of the exceptional qualities that distinguished Nelson Mandela. So was the letter of February 16th, 2000 that he addressed to me personally in which he apologized for having to reschedule one of our meetings. He explained that this was due to his need “to extend my stay in Arusha (Tanzania) with a few days since we are hoping to reach a breakthrough in the Burundi Peace Process”. (Between 1993-1999 a bitter and violent civil between the Hutus and Tutsis was raging in Burundi where 300,000 were killed. In December 1999, Mr. Mandela became facilitator of the Burundi Peace Process. His efforts led to the signing of the Arusha Peace and Reconciliation Agreement on August 28th, 2000.) He signed the letter, “I thank you for your support and cooperation”. That Nelson Mandela, always in the public spotlight, took the time and had the thoughtfulness to write such a personal letter in the midst of his public responsibilities and numerous challenges further reinforced the magnitude of his incredible stature.

Mr. Mandela finally met with over 200 representatives of the Jewish community. His sympathetic views on the Palestinians, and in particular his perspective on concessions by Israel to the Palestinians, were not widely accepted by this group (to say the least), but he was undeterred. I feared that he would be entering a lion’s den, but the audience listened and was civil. After his remarks, he graciously opened the floor and an interesting, lively Q & A followed, which Mr. Mandela handled with great skill and patience.

My sense was that Mr. Mandela was not even aware to the extent his ideas were at odds with those of his audience. He was convinced of the vision he wanted to share, his genuine commitment to resolving conflicts was passionate and absolute, and he could claim success as a peacemaker as no other. This was, after all, Nelson Mandela, Madiba, the father of a nation, a true champion of peace and freedom that he brought to his country and craved for people the world over.

Harriet Mandel

New York City, December, 2013

- No Comments

December 2, 2013 by Elizabeth Mandel

Goldieblox and the Three Girls

For Hanukkah, my daughters (ages 6.5, 4.5 and 1.5) are getting a range of gifts that are great for girls. These include K’Nex (my older girls just built an amazing roller coaster and are looking to expand their amusement park), a remote controlled robot kit (my eldest year old attended vacation robot camp over Veteran’s Day and filed the experience on her Things That Are The Best Ever list), Magnatiles and SnapCircuits.

For Hanukkah, my daughters (ages 6.5, 4.5 and 1.5) are getting a range of gifts that are great for girls. These include K’Nex (my older girls just built an amazing roller coaster and are looking to expand their amusement park), a remote controlled robot kit (my eldest year old attended vacation robot camp over Veteran’s Day and filed the experience on her Things That Are The Best Ever list), Magnatiles and SnapCircuits.

Yes, these gifts are great for girls. These gifts are great for kids, and surely girls fit into that category. These toys help children learn to follow directions, teach them spatial relations and encourage fine motor skills, give them opportunities for storytelling and cooperation, engage their imaginations and their innate interests in building, and give them a well-earned a sense of pride and accomplishment. They’re also really fun, which I believe is the best kind of learning.

This gift list does not include GoldieBlox, the much-hyped “engineering for girls” toy that hit the web with a sonic boom on Kickstarter last year, and has upped its own ante with commercial that has gone viral. If you haven’t seen it (you can watch it here), it features three girls who overturn media assumptions about what girls like by building an extremely sophisticated Rube Goldberg machine using, among other things, a pink tea set.

- 2 Comments

June 11, 2013 by Elizabeth Mandel

The Jewish Costs of Jewish Education

My husband and I long ago decided that a Jewish day school education was a top priority for us. I attended Jewish day school from pre-school through high school, and I feel that the daily immersion in Jewish texts and a Jewish environment during my formative years continues to enrich me spiritually and intellectually. My husband attended Hebrew school through his bar mitzvah. He found it stultifying, and he learned little. While he has spent time during his adult life studying, he feels like he can, in his own words, “never catch up,” the way a language learner who begins study in adulthood might feel impossibly behind next to someone who has been speaking a language since the age of three. He envies me the knowledge I wear like a second skin. And so, we decided we wanted our children to attend Jewish day to school to have the opportunity to rigorously delve into the Jewish texts, rich in their nuance and complexity; to be immersed in Jewish traditions, from the laws and rituals to the songs and symbols; surrounded by a love for Israel; steeped in the importance of giving and contributing to society. We wanted them to spend their days as part of the Jewish community. We found a school that reflected our world views, combining a liberal, progressive pedagogy with deep learning and a commitment to religious egalitarianism.

My husband and I long ago decided that a Jewish day school education was a top priority for us. I attended Jewish day school from pre-school through high school, and I feel that the daily immersion in Jewish texts and a Jewish environment during my formative years continues to enrich me spiritually and intellectually. My husband attended Hebrew school through his bar mitzvah. He found it stultifying, and he learned little. While he has spent time during his adult life studying, he feels like he can, in his own words, “never catch up,” the way a language learner who begins study in adulthood might feel impossibly behind next to someone who has been speaking a language since the age of three. He envies me the knowledge I wear like a second skin. And so, we decided we wanted our children to attend Jewish day to school to have the opportunity to rigorously delve into the Jewish texts, rich in their nuance and complexity; to be immersed in Jewish traditions, from the laws and rituals to the songs and symbols; surrounded by a love for Israel; steeped in the importance of giving and contributing to society. We wanted them to spend their days as part of the Jewish community. We found a school that reflected our world views, combining a liberal, progressive pedagogy with deep learning and a commitment to religious egalitarianism.

But then I became pregnant with and delivered our third child, and we became engulfed with worry about how we were going to afford tuition for all three girls. My husband and I began to examine the changes that we could make in our lives in order to be able to afford astronomical tuition costs. We already live fairly modest lives, and we knew that the change would have to be something significant, beyond cutting out the occasional dinner delivery. There were only two real places we could make such a change. We could move to the suburbs, where both living costs and tuitions would be less expensive, or I could stop freelancing as a documentary film producer, writer and editor, and go back to work full time. Since the birth of my first child I first worked part time and then moved to freelancing, with an extremely flexible schedule. This has enabled me to spend days at home with my children, as well as go on class trips and to doctor appointments, to be with them when they are sick, to be home when the babysitter is sick. It has enriched our family life and our individual lives in many ways – but not financially.

- 41 Comments

February 11, 2013 by Elizabeth Mandel

The Challenges of Raising Jewish Daughters

Raised in a Modern Orthodox home, I have long struggled with the contradictions I have found inherent in being both a committed Jew and a feminist. I have managed to carve my own path, create my own rationalizations, and find a space that makes sense to me at the juncture of my religious practice and my political and personal commitment to gender equity.

Raised in a Modern Orthodox home, I have long struggled with the contradictions I have found inherent in being both a committed Jew and a feminist. I have managed to carve my own path, create my own rationalizations, and find a space that makes sense to me at the juncture of my religious practice and my political and personal commitment to gender equity.

I am the mother of three girls, G, aged 5, P, 3, and M, two months old. Parenthood changes and challenges so many things, not the least of which is self-identity. It also requires one to articulate and form a cogent explanation for one’s choices, choices that previously required no justification. Becoming the mother of three girls has brought into high relief for me the challenges of living a life dedicated to both Judaism and feminism, and forced me to reflect closely on my priorities.

When G was born, I was frankly relieved that there would be no bris and that therefore I would not to have to throw a party eight days post-partum. Yet I was also unprepared for the strong sense of exclusion I felt at the lack of a religiously mandated ritual welcoming my precious, perfect first child into the community. What did this say about her value and worth to the community I expected her to cherish as much as I did, and which, I in turn, expected to cherish her?

My husband and I carefully designed a simchat bat (a baby naming ceremony, literally translated as “joy of the daughter”) to welcome G, incorporating ritual with personal expression. We held it in our synagogue, we included the rabbi, and it felt spiritually fulfilling. Yet, I could not escape the fact that it was voluntary, not mandatory, and that it was not something she shared with all other affiliated Jewish females the way a bris binds all affiliated Jewish males together. And indeed, when our second daughter was born, we neglected to hold the same ceremony for her. I justified this by telling myself that it was because I suffered a serious injury just prior to delivery and I was not fully mobile for several months afterwards; but the truth is, we would have held a bris no matter what the circumstances. There is something about a ritual being obligatory that makes it…obligatory.

- 9 Comments

January 3, 2011 by Elizabeth Mandel

Feminists In Focus: The Market For Organ Trade

I recently returned from the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam, Europe’s premier documentary film festival. It seemed apt, in a city infamous for its offering of everything for sale, to see Rama Rau’s “The Market,” the story of Sandra, a Canadian single mother desperately in need of a kidney, and the residents of a slum on the outskirts of Chennai, India, who are offering their kidneys for sale.

I recently returned from the International Documentary Film Festival Amsterdam, Europe’s premier documentary film festival. It seemed apt, in a city infamous for its offering of everything for sale, to see Rama Rau’s “The Market,” the story of Sandra, a Canadian single mother desperately in need of a kidney, and the residents of a slum on the outskirts of Chennai, India, who are offering their kidneys for sale.

I intentionally avoided writing “the residents…who are willing to sell,” because “The Market” skillfully raises and explores the question of what “willing” means, when there are no choices. For the people — primarily women — of Villivakkam, the commodification of their bodies is their only option; they must sell off the one thing they possess in order to keep themselves and their families alive. This question has been often explored in relation to sex work: when a woman, lacking opportunity, education, status and access to resources “chooses” prostitution, is it really a choice? In the words of one of the men who has sold his kidney, “We are fishermen by birth, we used to sell parts of the fish in the market but now we cut and sell parts of ourselves. They have made us the market.” (more…)

- 2 Comments

November 1, 2010 by Elizabeth Mandel

Feminists in Focus: A Peaceful Middle East

Welcome to the latest installment of “Feminists in Focus: Film News and Reviews,” an incisive look at the new film, Budrus, from filmmaker and Lilith contributor Elizabeth Mandel. Enjoy!

The media is replete with violent images of Palestinians, Israelis and Muslims; of veiled Muslim women subjected to the will of the men in their lives; of a sense of hopelessness regarding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The recent documentary film “Budrus,” directed by Julia Bacha, offers an alternative version to this story, and through that, hope for an alternative vision for the future. The film chronicles the events that unfolded in Budrus, a tiny (pop. 1500) Palestinian village on the West Bank, as the residents came together in nonviolent resistance against Israel’s separation barrier cutting through the village, its cemetery and its life-sustaining olive groves.

The media is replete with violent images of Palestinians, Israelis and Muslims; of veiled Muslim women subjected to the will of the men in their lives; of a sense of hopelessness regarding the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The recent documentary film “Budrus,” directed by Julia Bacha, offers an alternative version to this story, and through that, hope for an alternative vision for the future. The film chronicles the events that unfolded in Budrus, a tiny (pop. 1500) Palestinian village on the West Bank, as the residents came together in nonviolent resistance against Israel’s separation barrier cutting through the village, its cemetery and its life-sustaining olive groves.

In 2004, the construction of the barrier came to Budrus. It was scheduled to cut through the town, ostensibly unavoidably, for security reasons (no concrete reason is given for why the barrier takes a circuitous path that cuts through and isolates villages from their land and each other). In response, Ayed Morrar, a lifelong activist and six-year-veteran of Israeli prison, organizes “the Popular Committee Against the Wall,” a non-violent resistance movement designed to stop the progress of the barrier. At first it seems the protests are almost benignly endured by the Israeli military police assigned to Budrus. There is internal disagreement about whether the bulldozers should stop or continue. But soon, olive trees are being dug up, and it seems inevitable the protestors will be stopped and the barrier erected. (more…)

In 2004, the construction of the barrier came to Budrus. It was scheduled to cut through the town, ostensibly unavoidably, for security reasons (no concrete reason is given for why the barrier takes a circuitous path that cuts through and isolates villages from their land and each other). In response, Ayed Morrar, a lifelong activist and six-year-veteran of Israeli prison, organizes “the Popular Committee Against the Wall,” a non-violent resistance movement designed to stop the progress of the barrier. At first it seems the protests are almost benignly endured by the Israeli military police assigned to Budrus. There is internal disagreement about whether the bulldozers should stop or continue. But soon, olive trees are being dug up, and it seems inevitable the protestors will be stopped and the barrier erected. (more…)

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...