Author Archives: Eleanor J. Bader

August 29, 2016 by Eleanor J. Bader

Community Colleges Are Often Ridiculed. This One-Woman Show Prods Us to Value Their Students More.

ronnalevy.com

Ask most middle-class Americans to conjure up images of college students and they may picture Frisbee-throwing kids on a campus green, political protests, all-night cram sessions in a smoky room and beer. Lots of beer. But for the 50 percent of U.S. students who begin undergraduate life at a community college, more often than not commuting to school from their childhood bedrooms, the campus stereotype is completely disconnected from reality.

And actor-playwright-teacher Ronna J. Levy [ronnalevy.com] wants to be sure you know this.

Her one-woman play “This Gonna Be On the Test, Miss?” introduces audiences to the diverse students who’ve found their way into the developmental – sometimes called remedial – English classes she has taught for more than two decades. It also offers an insightful look into the joys and frustrations of teaching in this setting.

- No Comments

July 6, 2016 by Eleanor J. Bader

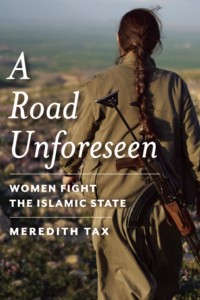

Writer-Activist Meredith Tax Gives Voice to the Women Fighting ISIS

Meredith Tax

Lord of the Rings author J.R.R. Tolkien wrote that “courage is found in unlikely places.” This truism, of course, has been repeatedly proven, as places steeped in poverty, neglect, hunger, and even war have produced unexpected exemplars of valor and fortitude.

Writer-activist Meredith Tax’s latest book, A Road Unforeseen: Women Fight the Islamic State—due out in late August from Bellevue Literary Press—zeroes in on a contemporary example of unanticipated moxie: The successful, if little-known, resistance to Muslim fundamentalism that has developed along the Syrian-Turkish border. In a newly-liberated region called Rojava, the towns of Afrin, Cizire and Kobane are currently under the control of a secular, multiethnic confederation of Arabs, Armenians, Assyrians, Chaldeans, Chechans, Kurds and Turkmen.

Writer-activist Meredith Tax’s latest book, A Road Unforeseen: Women Fight the Islamic State—due out in late August from Bellevue Literary Press—zeroes in on a contemporary example of unanticipated moxie: The successful, if little-known, resistance to Muslim fundamentalism that has developed along the Syrian-Turkish border. In a newly-liberated region called Rojava, the towns of Afrin, Cizire and Kobane are currently under the control of a secular, multiethnic confederation of Arabs, Armenians, Assyrians, Chaldeans, Chechans, Kurds and Turkmen.

Women, Tax reports, make up 40 percent of all organizations in Rojava, including those involved in local administration and decision-making. What’s more, every committee and oversight agency is led by one man and one woman, a conscious effort to promote female leadership and confront patriarchal cultural norms head-on.

Tax sat down with Lilith in late June to discuss activism, social change and women’s empowerment.

EJB: When did you become a feminist?

MT: I grew up in Milwaukee and my family was really sexist. As a kid in grade school I was told that a girl should not be too smart; my parents made it clear that no one would want to marry me if I did not tone it down. I was confused and didn’t understand why a boy wouldn’t want to be with someone who could help him with his homework! In sixth grade I started a petition to demand that girls be allowed to run for class president. As I got older I became more and more disgusted by the limited social possibilities for a girl like me. Reading saved me. Even before I left for college I’d read novels by Louisa May Alcott and plays by George Bernard Shaw that introduced me to feminism. I’d also read about the suffrage movement. Later, I went to Brandeis but even there, among a lot of smart women, our options were limited. After we graduated we could be teachers, social workers, or get a low-level job in publishing. I didn’t want that. I wanted to be a writer.

EJB: And you did! How did you make that happen?

- 1 Comment

June 20, 2016 by Eleanor J. Bader

Vivian Gornick on Feminism, Friendship, Gentrification, and Our Mothers

Vivian Gornick. Photo by Mitchell Bach.

“I’ve always felt like an outsider,” three-time National Book Award nominee Vivian Gornick confesses. “I used to have a dream, a bad dream, in which I was in a strange building. When I walked through the door I saw that the entire inside had been scooped out and I had to climb a rope to get to the top floor. Once there I found myself in the Bronx apartment I had grown up in. In the dream I asked myself how I’d gotten there. It was both dramatic and horrible.”

It’s a startlingly honest, if jarring, revelation, for despite the 81-year-old writer’s considerable literary success—and an output that includes dozens of articles and 12 highly-lauded books—Gornick seems genuinely shocked, perhaps even bewildered, by the esteem in which she is held. Throughout our 90-minute conversation—in one of the few diners left in Manhattan—she is warm, thoughtful, witty, and open. Our conversation is sprawling, not only touching upon the recent paperback release of her 2015 book, The Odd Woman and the City, but addressing feminism, Hillary Clinton, friendship, gentrification, walking, teaching and our mothers.

- No Comments

April 28, 2016 by Eleanor J. Bader

“No One Working for Social Justice Should Expect Their Opponents to Just Go Away”

Marlene Gerber Fried

Marlene Gerber Fried, Faculty Director of the Civil Liberties and Public Policy Program at Hampshire College, and a founder both of the Abortion Rights Fund of Western Massachusetts and the National Network of Abortion Funds, has been a reproductive justice activist since the 1970s. You’d think she’d be burned out by now, but she’s not, and despite a flurry of recent legislative setbacks—the Guttmacher Institute reports that 57 new abortion restrictions passed statehouses in 2015—she’s not even discouraged.

“Sure, I sometimes shake my head in disbelief that we still have to fight these battles, but no one working for social justice should expect their opponents to just go away,” she begins. “You have to have a long view.”

That attitude has allowed Fried to celebrate both small, incremental victories and the positive ideological shifts that she’s seen over the past several decades.

She is heartened, for example, by how much the reproductive rights movement has changed, moving from the single issue of abortion to reproductive justice, an anti-racist, anti-sexist framework that includes trans rights, sexual justice for the disabled, and support for programs that support childbearing—from quality public schools, to nutritious, affordable food and clean water and air. In addition, the growing number of R.J. organizations, many of them led by young people of color, inspires Fried and keeps her energized and optimistic.

- No Comments

March 9, 2016 by Eleanor J. Bader

(81-Year-Old) Actor-Singer-Comedian D’yan Forest Is Bawdy, Energetic and on the Road

When D’yan Forest stood on stage at the Gotham Comedy Club in New York City for the first time, she had no idea if anyone in the audience would laugh during her six-minute set. But they did.

When D’yan Forest stood on stage at the Gotham Comedy Club in New York City for the first time, she had no idea if anyone in the audience would laugh during her six-minute set. But they did.

That was a decade ago, when the actor-comedian-singer-chanteuse was 71. “I was scared of heckling,” Forest admits. “I was afraid no one would want to listen to an old Jewish woman. Before this experience, I’d spent decades singing on stage. In fact, I’ve been performing since I was a child, but when people laugh and applaud at a comedy club, well, I get naches, great pleasure, from it.”

Forest’s smile widens as she sits back in her chair to discuss her life’s trajectory. Born in 1934 in Newton, Massachusetts—one of the few Boston suburbs that welcomed Jewish residents—she describes her family as “conservative Republican.” Nonetheless, by the time Forest was eight or nine, her mom had become an adherent of Jewish Science, a spiritual movement that emphasizes the role of affirmative prayer, divine healing, and the importance of maintaining a positive attitude. At the same time her mother loved to throw large parties and tell off-color stories and jokes to her friends and neighbors. Unbeknownst to the adults, young D’yan would eavesdrop from the home’s second floor.

Forest found the narratives alluring—even when she did not fully understand them—and something inside her clicked.

Still, despite these occasional forays into impropriety, the era’s gender boundaries were rigid, and Forest—whose birth name was Diana Shulman—understood that she was expected to marry “a nice Jewish boy” when she came of age. So she did. After graduating from Middlebury College, where Forest was the only Jewish female, she accepted a proposal from an ambitious young attorney. The liaison lasted for four years. “He did not know how to pleasure a woman,” Forest laughs. “I was a stupid virgin when I met him. If I had fooled around before marriage I would have known not to marry him.”

- 1 Comment

February 9, 2016 by Eleanor J. Bader

Which of These Heroic Holocaust Women Have You Heard of?

Stein with Sculpture, 2010

Feminist artist Linda Stein wants every human being to be what she calls an “upstander,” not a bystander. Whether this means speaking out against oppression; defending someone who is being bullied, ostracized, or persecuted; or simply showing compassion to a person in need, her work is meant to encourage action over passivity.

Her most recent effort, a series of tapestries, sculptures and collages, is called Holocaust Heroes: Fierce Females, and pays homage to 10 women, half of them Jewish and half of them not, who exhibited almost-unimaginable “upstanding” courage during World War II.

Some, like Anne Frank (1929-1945) are well known. Others, like Vitka Kempner (1920-2012) are not. Kempner was a leader in the resistance that formed in Lithuania’s Vilna ghetto, and, as part of the United Partisan Organization, was the first woman to participate in blowing up a Nazi train. Other women memorialized by Stein include Noor Inayat Khan (1914-1944), the first female radio operator to be sent from Britain to assist the French resistance; Nancy Wake (1912-2011), a New Zealand native who became an underground courier; and Ruth Gruber (still alive at 104), an American journalist and photographer who not only interviewed camp survivors after the war—bringing their stories to international attention—but had earlier risked her life to rescue 1,000 Jewish refugees and wounded American soldiers.

- No Comments

December 9, 2015 by Eleanor J. Bader

What You Don’t Know About Jews and Abortion Access

It’s ubiquitous: Go to any abortion clinic in the United States and you’ll likely see protesters out front chanting the Rosary, holding pictures of Jesus, or screaming about God’s love of fetal personhood. Sometimes affiliated with a local parish, the protesters rant, rave, berate, and cajole, and even if they don’t stop the woman from entering the clinic and having the procedure, they work overtime to get inside her head. Given this pervasive presence, it’s not surprising that most Americans assume that all religions oppose abortion and the use of contraceptives. But they don’t. And never have.

A Time to Embrace: Why the Sexual and Reproductive Justice Movement Needs Religion, a new report written by the Westport, Connecticut-based Religious Institute, corrects this misimpression and briefly traces the history of religious support for birth control, and later, abortion, LGBTQ rights, and the freedom to marry. The report also provides an insightful overview of how and why this support has waxed and waned over the past 85 years.

“Protestant and Jewish clergy were centrally involved in the early days of the birth control movement,” the report begins. In fact, in the 1930s, numerous denominations passed resolutions in support of contraception and formed the multi-faith National Clergyman’s Council to support its promotion. Rabbis, ministers and lay religious leaders also got involved in the American Birth Control League, the precursor of the Planned Parenthood Federation of America. Then, in 1967, a group of 21 clergy—19 ministers and two rabbis—publicly announced the formation of the Clergy Consultation Service on Abortion (CCSA), a well-vetted referral network that grew to include 1,400 professionals and helped more than 100,000 women secure a safe, if still illegal, abortion. These preachers, the report continues, were outspoken risk-takers who openly touted breaking an unjust law. And they prevailed.

- 1 Comment

October 7, 2015 by Eleanor J. Bader

Rape in the Middle East and Women-Led Organizing: Is Social Change on the Horizon for Syrian Refugees?

As desperate refugees continue to stream into Europe in response to the Syrian Civil War and ISIS brutality, it’s easy to become overwhelmed or grief-stricken. But Yifat Susskind, sees a modicum of progressive social change on the horizon for those most affected by the crisis.

© Maureen Drennan

Susskind, Executive Director of MADRE, a 32-year-old women’s human rights organization, is chatting with me in MADRE’s Manhattan office, moving between her personal history as an Israeli-born kibbutznik and the horrors facing women in war-torn areas the world over. Then, she matter-of-factly mentions something shocking. “So many women have been sexually abused by ISIS that it is possible to overturn the social norms that rape survivors in the region often experience,” she goes on. “The idea that rape is the woman’s fault falls apart when it is happening to everyone. As a result, women who have been raped are no longer seen as damaged goods, but are instead being hailed as returning prisoners of war who need to be reintegrated as heroes.”

It’s an amazing turn, but Susskind makes clear that this kind of shift is not anomalous, just little known. What’s more, it is not the only sea change being ignored by mainstream media. Indeed, she reports that there is a great deal of organizing going on in improbable places, much of it women-led.

To Wit: Over its three decade history, MADRE –“mother” in Spanish – has partnered with women’s groups in Colombia, Guatemala, Haiti, Iraq, Kenya, Nicaragua, Palestine and Syria. Their efforts are two-pronged: Raising money for organizations providing hands-on social services and advocating for policies that benefit women, girls and families affected by violence.

© Meena Lenn

In Colombia, this has meant pairing with Taller de Vida, a group that provides art therapy and trauma counseling to former child soldiers. In Guatemala, MADRE has worked with a women’s weaving collective to help preserve a traditional art form and raise money for low-income communities. In Kenya, they’ve joined with the Indigenous Information Network to teach women how to preserve food and collect rain water in areas suffering through drought and severe climate change. And in Iraq they’ve helped support a Women’s Peace Farm for female agricultural workers displaced by war. With the Organization for Women’s Freedom in Iraq [OWFI] they have created an underground railroad for girls and women fleeing ISIS-controlled areas and have raised funds to establish a safe house for them. In the West Bank their work has involved supporting Midwives for Peace to ensure better birth outcomes and improved maternal health in that sorely underserved area.

Since 1983 MADRE has raised about $31 million for these and other projects. Right now, Susskind says, they’re coordinating fundraising for the creation of a rape crisis center and shelter in Kurdistan, to serve women and girls fleeing sexual slavery as well as LGBTQ Iraqis who, she says, “are especially threatened in this super-reactionary climate.” Once the goal of $150,000 is reached–they are hoping for late fall–the center will open its doors. “Many of the women and girls who will use the shelter have nowhere else to go,” Susskind explains. “Their families have been killed and they need immediate medical and psychological help in order to heal.”

© MADRE

Still, while Susskind values direct service, she is pleased that the center will also promote political activism, including support for a campaign to overturn a prohibition on privately run shelters for survivors of domestic abuse. “Right now the Iraqi government does not allow women’s groups to run residences for battered women. Those that disobey are frequently raided by police. If they were allowed to operate openly, the raids would stop,” she says. In addition, under current law, an Iraqi woman needs her husband’s consent to obtain an ID card. Without this document, she is ineligible for food rations and housing. Not surprisingly, MADRE has joined with OWFI and other organizations to push for an end to this policy.

They’re up against mighty foes, both religious and secular, but organizing as women for women is incredibly powerful, Susskind says. “When we mobilize as mothers, it means we’re prioritizing the needs of the most vulnerable people. If we can get governments to focus on these groups, whether in terms of economics, war, or nuclear proliferation, we’ll be a lot closer to what we want to see in the world.”

Susskind herself is the mother of two boys and has been at MADRE since 1997 and executive director of the organization since 2011. “I was born in 1967 on a kibbutz near the Lebanese border,” she tells me. “My paternal grandparents founded the kibbutz in the 1930s and my dad was born in 1948, the year Israel was created. They were the quintessential Jewish family: Ashkenazi, secular and Zionist.”

Her American-born mother’s history stands in stark contrast. Nonetheless, here too Susskind was exposed to political ideas at an early age. She describes her Russian-born maternal grandmother as typical of early 20th-century Jewish immigrants: A socialist, atheist, union supporter who worked in the garment industry.

“My mother’s mother taught me about Jewish ethical practice,” she says. “It was from her that I learned that to be Jewish is to be part of an historical continuum. She taught me to honor the visionary people who came before me, whether they were abolitionist Quakers, pacifist World War I opponents, or Jewish trade unionists.”

In fact, Susskind sees her work at MADRE as ensuring the historical continuity of oppositional politics. “Right after I finished college I went to Jerusalem to organize support for ending the occupation,” she says. This introduced her to joint Israeli-Palestinian human rights groups as well as Women in Black. She did this work for six years and returned to the US in 1997.

Does the work ever get you down? I ask, wondering how she and her co-workers stay sane in the face of so many atrocities. Susskind takes a minute and smiles widely before continuing. “There is great joy in this work because it is fundamentally about making things better,” she says before pausing. “I’m not at all religious but the Jewish teaching that we are in partnership with creation resonates with me. So does a statement attributed to [Mishnah sage] Rabbi Tarfon: ‘It is not incumbent upon you to complete the work, but neither are you at liberty to desist from it.’”

After this brief nod to the Pirkae Avot, Susskind turns to the pile of papers on her desk. “The work will not be finished in my lifetime,” she shrugs, “but I will do as much as I can to promote peace and justice.”

- No Comments

June 29, 2015 by Eleanor J. Bader

What Motivates an Activist?

As a five-year-old girl, activist/journalist/playwright/lawyer Cynthia L. Cooper was unfamiliar with the word feminist and, like most of her peers, knew nothing about human rights or social justice. But she knew what was fair, which is why she took umbrage over privileges that were extended to her brothers, but not to her.

“I remember it as a moment of outrage when my brothers got to play baseball and I didn’t,” Cooper told Lilith. “I was also as good as or better than the boy down the street. It made no sense to me that he was able to join Little League and I wasn’t.”

It’s been many decades since this affront, but Cooper’s affinity for the excluded remains ironclad, and whether she is writing articles about the current spate of sexual attacks on college campuses, books—on themes as disparate as wrongful criminal convictions, the abuses of the Bush/Cheney administration, or tenants’ rights—or plays about sexual violence, reproductive justice, the Holocaust, or women in sports, her passion for equity is evident.

Cooper grew up in a suburb of Cleveland, Ohio, and learned her family’s history through stories that were told by the adults. There was her dad’s chronicle of moving from Lithuania to Reading, Pennsylvania, and her mom’s coming-of-age in tiny Dawson, Minnesota, where hers was the only Jewish family for many miles. “My grandfather, my mom’s dad, owned a general store,” Cooper begins. “Their family was isolated in terms of Judaism but they were nonetheless central to the community. I heard many accounts of how, during the Depression, my grandfather gave people food if they needed it.” His generosity, she continues, was near-legendary, in one instance prodding him to buy a farm that was being foreclosed in order to protect the destitute people living on this land from being evicted. “I absorbed the message that you should do things for other people,” Cooper says. “That was Judaism for me; you do something bigger than yourself.”

- No Comments

June 15, 2015 by Eleanor J. Bader

This Artist Teaches Woman Power

“Evening’s Flight,” Archival Pigment Print. © Sara M Novenson 2012

The first thing you notice when looking at Sara M. Novenson’s paintings are the colors: Rich and vibrant, the blues, pinks, purples, reds and yellows invite you to peer closely, and whether you’re perusing her Great Women of the Bible series or her landscapes, the limited-edition work is striking. What’s more, most of Novenson’s art is bordered by hand-painted Hebrew letters—excerpts from the Psalms as well as blessings—that remind us to appreciate the miracle of creation.

Collectors of Novenson’s work include actor Fran Drescher, the late musician Frank Zappa (1940-1993) and the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York and she has had exhibitions throughout much of the world. Novenson has also run her own gallery on Santa Fe, New Mexico’s famed Canyon Road since 1996.

A reviewer, writing in the Santa Fe Focus, describes her creations as “dazzling,” with “life-inspiring rays of sun and people shimmering with power and beauty.” But most notable, the reviewer wrote, is “the female energy and spirituality” each painting exudes.

This, Novenson told Lilith, is exactly what she intended. In fact, her Women of the Bible series aims to imbue viewers with a better understanding of female power, and whether they’re seeing images of Deborah, Esther, Hannah, Judith, Leah, Miriam, Naomi, Rachel, Rebecca, Ruth or Sarah, she hopes they’ll walk away feeling “empowered from both within and without.”

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...