by Eleanor J. Bader

Which of These Heroic Holocaust Women Have You Heard of?

Stein with Sculpture, 2010

Feminist artist Linda Stein wants every human being to be what she calls an “upstander,” not a bystander. Whether this means speaking out against oppression; defending someone who is being bullied, ostracized, or persecuted; or simply showing compassion to a person in need, her work is meant to encourage action over passivity.

Her most recent effort, a series of tapestries, sculptures and collages, is called Holocaust Heroes: Fierce Females, and pays homage to 10 women, half of them Jewish and half of them not, who exhibited almost-unimaginable “upstanding” courage during World War II.

Some, like Anne Frank (1929-1945) are well known. Others, like Vitka Kempner (1920-2012) are not. Kempner was a leader in the resistance that formed in Lithuania’s Vilna ghetto, and, as part of the United Partisan Organization, was the first woman to participate in blowing up a Nazi train. Other women memorialized by Stein include Noor Inayat Khan (1914-1944), the first female radio operator to be sent from Britain to assist the French resistance; Nancy Wake (1912-2011), a New Zealand native who became an underground courier; and Ruth Gruber (still alive at 104), an American journalist and photographer who not only interviewed camp survivors after the war—bringing their stories to international attention—but had earlier risked her life to rescue 1,000 Jewish refugees and wounded American soldiers.

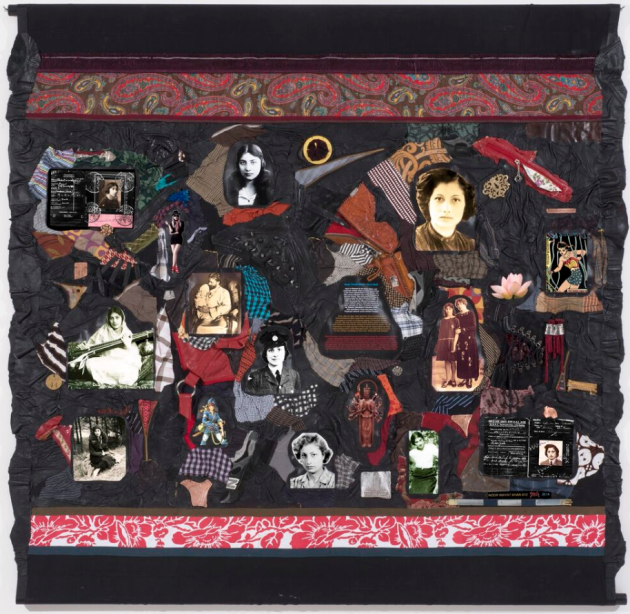

“Vitka Kempner 815” 2014 fabric, archival pigment on canvas, leather, metal, zippers 5 ft. sq.

Stein sees these women as awe-inspiring, but notes that the project is meant not only to exalt, but also to correct, bringing attention to the valorous women who’ve been left out of the historical record. “There is a deficit in terms of who is remembered,” she explains. “Women who played a heroic role during the Holocaust have been forgotten in much the same way that female first responders on 9/11 have been forgotten. I want these women to be remembered, credited, and integrated into people’s consciousness.”

Her medium: art.

Stein has created a separate, five-foot square, quilt-like tapestry for each of the 10 selected women. Objects, words, and photos have been transferred onto a fabric backing to highlight the distinct contributions each woman made. Twenty smaller, collage-like sculptures augment the tapestries and combine seashells with metal or wooden spoons and found objects. The end result references the emotional abuse and sexual violence that were endemic in the camps.

“Noor Inayat Khan 813” 2014 fabric, archival pigment on canvas, leather, metal, zippers 5 ft. sq.

The “spoon-to-shell” sculptures were inspired, Stein tells me, by Rochelle G. Saidel and Sonja M. Hedgepeth’s 2010 book, Sexual Violence Against Jewish Women During the Holocaust. One story was particularly impactful for her. It recounts the experience of Leah, a woman imprisoned in Birkenau, who was offered a spoon by a Polish worker. When Leah realized that the man expected her to exchange sexual favors for the utensil, she balked. “She made this choice in spite of the fact that a spoon was literally a life saver in the camps,” Stein says. “Without it, a prisoner had to drink from the same vessel as everyone else. People feared that the edge of the bowl had tuberculosis germs, and more, on it. A spoon was like gold.”

“Spoon to Shell 817″ 2015 spoon, shell and mixed media 11″x 14″x” 2″.

Stein takes a deep breath, and makes sure to look me in the eye before continuing. “After Leah refused the offer and threw the spoon at the man, he went and found another woman who was only too happy to accept the deal.”

As she speaks, Stein’s tone is pensive. Nonetheless, her eyes wander to take in the beauty and warmth of her well-lit gallery. Located in a posh area of lower Manhattan, the fact that we’re sitting in safety and comfort is not lost on us.

After a few quiet moments to let the magnitude of our privilege sink in, Stein again begins talking. The shells, she continues, are symbolic. “Elie Wiesel wrote that when he was in Auschwitz and Buchenwald, he felt like his face had to be a mask, a shell that hid how he actually felt. Even when he watched his father getting beaten by the Gestapo, he could not let his face show his fury or he would have been beaten, too.”

Despite the heinous nature of what she is describing, Stein emphasizes that her interest is in how people survive and retain their humanity—not in how they experience abuse. In fact, the former art teacher, school district artist-in-residence, and professional calligrapher admits that she has long been interested in—or perhaps obsessed with, she laughs—the idea of protection, and is intrigued by the possibility that some people may have a genetic predisposition to empathy. “Do you think that’s possible?” she asks me. “Or do you think empathy has to be encouraged, learned?”

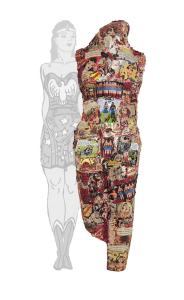

Addressing these themes is not new for Stein. In fact, an earlier series called The Fluidity of Gender involved crafting wearable body armor. That project addressed not only the gender binary, but also how we keep ourselves protected and safe. According to art critic Joyce Beckenstein (writing in the summer 2013 issue of Surface Design), the works depict the “knight as able-bodied woman who in a variety of guises, emerges as a champion, a bulwark to all who fall into her embrace.”

As Stein produced the life-sized sheaths—made of cloth, wood, metal, stone, shells, glass and other materials—she included visual depictions of female protectors such as Wonder Woman, Princess Mononoke and Kannon, a female Buddhist icon. As she explored domination, submission and security, she says that she kept thinking about bullying. Hitler quickly came to mind. “The Fluidity of Gender made me think about protecting myself and protecting others. It seemed like a logical progression to move from these subjects to the Holocaust,” she says. She soon began listening to Shoah-themed audiobooks while she worked; she credits texts including The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, The Boy in the Striped Pajamas and A Train in Winter with helping her zero in on the Holocaust heroes she wished to showcase.

As she names the books that influenced her, Stein moves her hands a bit before switching gears. “I want you to know that my use of the word hero, not heroine, was intentional,” she says. “There is no gender for heroism. We don’t need a feminized form of the word. Not everyone agrees, but that’s okay. The response I got from the decision to call females fierce has also been interesting. Some people told me not to use it, that it implied violence, but I see the word as meaning determined, impassioned and intense.”

“Justice for All 698″ 2010 acrylicized metallic paper, archival inks, mixed media (vinyl) 79″ × 24″(40″) × 9”.

“To me,” she adds, “not using words like fierce to describe women is a kind of self-censoring. It’s an everyday form of sexism. I want to bring attention to the fact that most of the people celebrated and acknowledged for bravery are male. I want people to think about the reasons for that.”

Her own a-ha moment came after reading Nancy Wake’s 2011 obituary in the New York Times. “Shortly after seeing her obit I had a conversation with art historian Gail Levin. We were talking about what the Jewish people had gone through, not only during the Holocaust, but throughout history. I am not at all religious but at that moment I knew that I wanted to eventually do something to honor Jewish heroism and the many women who have resisted anti-Semitism, sexism and repression. Of course, the Holocaust is part of my heritage, just as the desire to stand up to evil is part of me. I knew that someday, in some way, I would have to do a project around these themes.”

This resolve eventually led Stein to develop Holocaust Heroes: Fierce Females. The traveling exhibition is being sponsored by Have Art Will Travel, Stein’s non-profit art education initiative, and has already been displayed in Boca Raton, Florida. It will be in Santa Barbara, California from March 3-29, in New York City’s Flomenhaft Gallery from April 28-June 25th, and will travel to Milwaukee’s Alverno College next August. More information is available from lindastein.com.