fiction by Tamar Ben-Ozer

The Miscreants

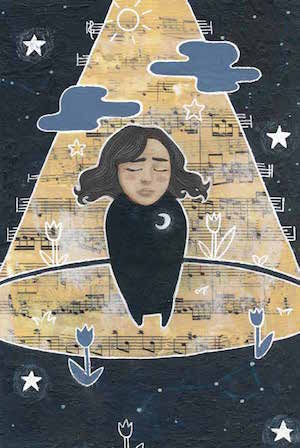

(Art by Michaela MacPherson, michaelamacpherson.com)

I played Bach’s Prelude in C Major on Mrs. Z.’s piano this afternoon. Mrs. Z. is our downstairs neighbor, and she’s old, maybe 70. Since we don’t have a piano at home, she lets me come over on weekdays to practice on her crumbling baby grand. Her husband died two years ago, in 1945, and their children all left for Palestine with their spouses and kids. She rarely leaves the house anymore because of her Parkinson’s, so I’m pretty much the only person she talks to most days. I sang while I played, Gounod’s “Ave Maria”, just like Miss Weil showed me during yesterday’s lesson. Hear how Bach’s Germanic harmonies sit perfectly underneath Gounod’s French melody. Baroque and Romanticism perfectly entwined, reckless emotion and meticulous structure in flawless symbiosis. I sat still for a long time, quietly contemplating the two partitures in front of me.

“Rikki, come wash up for Shabbos,” Mama’s voice called me through the open window. I kept playing until I reached the end of the piece. The last chord rang out while I kept my foot on the pedal. I held my breath until every last decibel had disappeared into the ether.

“Coming!” I yelled out, and began packing my notes into a manageable stack of papers I could stuff into my bag. Mrs. Zaitlin was having her tea in the other room. Unlike my family, she does not keep the Shabbos. Keep the Shabbos. That’s what we call the strange practice, perhaps for lack of a more appropriate term. I’ve always found it peculiar, to speak of keeping a day. When I was younger Papa would tell me that we do it to prevent the day from slipping through our fingertips. To stop time: to watch it from the outside looking in, as if life were a snow globe or a film.

Mrs. Z. used to be more religious, back when her family was still around, but now she says offhandedly observance is a tribal practice and is not easily maintained on one’s own. At first Papa would invite her to have the three Shabbos meals with us right after her youngest son left, but she’d always decline, and eventually he stopped asking.

In addition to being a pious Jew, Papa is also a Zionist. So are Mrs. Z.’s children. They left their mother alone in the withering Jewish quarter of our Transylvanian town so they could go live an ideological ideal in the Promised Land. Her youngest son and his newlywed wife packed up their belongings last summer: blouses and a white tie; a sterling silver, handmade candlestick set that had been in the family for generations; a rusted shovel he thought would prove useful in working the land. I snuck into their kitchen and asked him to stay, please, I’d said, your mother is sick, your wife is pregnant, and you don’t even believe in God, so why go there? He ignored me and they left. His mother was rendered a sort of adult orphan, but as they were her children it was hard for them to see.

I swung my bag over my shoulder and stepped into the kitchen to say goodbye.“Ah gutten Shabbos.” I spoke the familiar parting words, leaned over and kissed the age spots on her soft and wrinkled cheek. Her skin was thin as wrapping paper.

“Ah gutten Shabbos, my dear.” She cupped my face in her trembling palms and pressed it close to hers.

Later that evening, after we’d finished eating and reciting the food blessing, I excused myself from the table, saying I’d forgotten something at Mrs. Z.’s house. I’d been doing this every day for the past month and a half, finding some excuse to get away and slip into her home once the sun had set. This practice demanded a certain degree of stealth on Fridays, to ensure my parents didn’t ask any prying questions.

Once I made it to her apartment, I made sure all the curtains were shut. I walked through her three-room home and ended up in the bedroom, where Mrs. Z. lay waiting for me in her large antique bed. I walked over to her night-stand in the dark. On it lay a Yiddish translation of Gulliver’s Travels. A small medicine jar. A tall glass of water with a straw. I lifted the box of matches that lay by a dark blue candle, its color barely visible by the slivers of moonlight that shone through an obstinate crack in the drapes. It was a simple task, but one she could no longer manage herself, lacking sufficient control over the muscles and joints in her fingers. As I removed a match from the box a familiar chill raised the hair on my forearms. I sensed with a formidable surety that somehow Papa could see me, about to severely defy the Jewish code of law. I struck it quickly. The flame grew before my eyes as I brought it towards the wick and lit the candle.

A warm glow appeared by her bedside. It overpowered the moonlight and illuminated our faces in flickering light and dancing shadows. She smiled at me and placed the book in her lap, opened it to where the bookmark lay in one of the first chapters. She scanned the lines with her finger until she found her place. I made a half-turn away from her and waved the burning match around until it extinguished itself in a cusp of smoke, closed the matchbox and returned it to the nightstand. With a wave and good-night I exited towards the living room.

I paused to look around before leaving. There were shelves upon shelves upon shelves of books, their titles, all of which I knew by heart, obscured in the darkness. Leather-bound editions of the Babylonian Talmud and Maimonides commentaries; Bibles and Siddurs, prayer books; two shelves devoted entirely to Kabbalah teachings. Silent, dust-covered mementos of her deceased husband. He had always kept the faith alive in their house, defying his heretic wife. She stopped attending synagogue long ago, preferred to spend that time taking walks through the city or playing music at home.

Mrs. Z. used to be more religious, back when her family was still around, but now she says offhandedly that observance is a tribal practice, and is not easily maintained on one’s own.

Once, years ago, she went to Paris. She told no one but her husband and reappeared, weeks later, smelling of for-eign perfumes, a vibrant green scarf wrapped around her hair and tall, gold-studded leather boots on her feet. No one she knew had traveled farther than neighboring Hungary, where they would often go visit family before the War. When she returned, she became the talk of the town, her name spoken askance in whispers at synagogue and overheard in the women’s conversations at the market.

She told me stories of her adventures, over tea when I took breaks from practicing. The concerts she’d attended at the Opéra Bastille, how she had met Debussy and Satie; had approached them audaciously and shaken their hands, introduced herself in what I imagined to be impeccable French but in reality was just miscellaneous bits and pieces of the language. She used the proper accent when pronouncing their names, pucker-ing her lips on the vowels. She spoke animatedly and raised her hands as they trembled, carried them up and sideways to illustrate the tale. It was as though she was shaking them on purpose: jazz hands invoking the zeitgeist of the 20s.

In bed that night I looked out the window at the stars. I saw Orion’s Belt and the Great Bear. I recognized Betelgeuse, the star closest to Earth, except for the sun. My younger sister was asleep on the other side of the room, her breathing soft and regular, pacing my own inhalations and exhalations. The starlight would suffice, I thought. I reached under my bed, took out papers and a pencil, and started to draw with a feverish imperativeness.

I drew dense forests and woodland creatures from the basin of my subconscious. Awake, I dreamt in outlines and sketches of trees. A hare was caught in the air mid-jump. It spread its paws forward and they merged with the bark and the leaves. Swirling upwards, you couldn’t tell where fur ended and flora began. Grey pencil marks invoked shades of green and brown, a dawning purple sky. In lieu of a sun, a flickering flaxseed candle dripped tears of wax into the lake.

I woke up the next morning, graphite on my fingertips and the pencil clutched in my hand. Mama stood in the doorway. As per usual, she’d come to wake me up to eat. Our eyes met across the room and I saw that she’d already noticed the pencil in my hand, already registered my heresy and connected it to my time spent with Mrs. Z.

Two days later, I came home from school to find a black Steinway piano perched up against a wall in our dining hall. I walked over and gently fingered the keys. I stood upright at its far left; I didn’t want to sit down and validate its existence just yet.

“Now you can practice at home.” Mama’s smiled a smile that ended at her cheekbones, pursed her lips and clasped her hands to her chest.

“Yes. Finally. Yes, thank you so much,” I said flatly.

Tamar Ben-Ozer is an editor at The Jerusalem Post. She recently completed a degree in vocal performance and writes and sings in Tel Aviv. This story was written “in loving memory” of her grandmother, Masha Ben-Ozer Shomroni.

Please wait...

Please wait...