Harriet Goldman

The Curiosa Section

2017 Lilith Fiction Contest: Second Place

J. Rothenburg Used and Rare Books on Fourth Street displayed a yellowing dictionary on a stand in its window alongside some antique maps that looked as if they’d been placed there when Columbus set sail. Charlotte Silver squinted into the shop, one flight down from street level and worlds away from the sunny day outside. She screwed up enough courage to ask the man hunched at the desk—J. Rothenburg, she figured—for books by Havelock Ellis, the scientific sex researcher. The eyebrows on his hangdog face lifted. “You’re not from the Vice Squad, are you?”

“No, I’m a nursing student,” said Charlotte. She removed her white gloves so he could see her wedding ring and know he wasn’t contributing to the corruption of a minor. As an unseen clock ticked in the airless room, she held her breath and reassessed her white straw hat. Was it too plain—something a police decoy might wear—or just plain enough to be owned by a poor student? But Charlotte’s disguise wasn’t her hat or her gloves, it was the attitude she’d been cultivating in the street car all the way to Manhattan from Williamsburg, Brooklyn, after having proved too shy to ask for this book from the same librarian who had been stamping her selections since she began to read. At the library she had been hoping for nothing less than to understand what had transpired between her and Martha this summer, and had left because she was afraid the librarian would ask her what business she had in requesting such explicit material. Now she did her best to affect the persona of a nurse, efficient and aloof, a woman on a scientific mission. She willed herself to remember one certain thing – she would never see J. Rothenburg again.

“You’re really a nurse, right?”

“A nursing student.”

“Does your husband know you’re here?”

“My husband is at home with our little boy,” she said. At least that much was true. In the three months since she’d met Martha she’d been living with Perry as if she were Charlotte Silver’s accomplished understudy, and Perry seemed to suspect nothing. All he knew was that he had accepted a job as director of Camp Idlewild to get his family away from the city during the time of the year when polio was the most contagious, and they had all come back healthy and strong.

“If anyone asks, I’m going to say you said you’re a nurse. Where do you go to school?”

Charlotte had already thought of an answer to that question. “Beth Israel,” she said, because all the Jewish nurses studied there.

“You’re not Catholic?”

“No, I’m Jewish.”

“Because the cops are Catholic. They say they’re enforcing the Comstock Laws, that would be bad enough, but last time I looked we are in the year of their Lord, nineteen forty-four and the Pope is still deciding what they read. And don’t let them tell you any different.”

“I’m not Catholic. I’m Jewish.”

“You know why I believe you? Because it’s Saturday, and none of those barbarians work on the weekend, unless they’re busting into bordellos or fairy bars. Then they get zealous. But books…they don’t understand books. They aren’t going to bother on a Saturday.” He lifted himself out of his chair. “I’m not saying I have it,” he said, as he indicated that she should follow him along the narrow path between the rows of books stacked in front of packed shelves. Once again, she had lied and someone had believed her, just as Perry believed her when she had said she was just going to spend this afternoon with a friend who was ill, and all through the summer, when she had said Martha, the swimming instructor, was just teaching her how to swim.

Charlotte could pinpoint the moment deceit had become second nature. It was the afternoon of the swimming lesson. She and Martha were waist deep in Lake Idlewild surrounded only by the red-winged blackbirds displaying their colors and flitting between the reeds. Charlotte had been trying to place her face in the water. Time after time, her lungs became stiff with air she couldn’t seem to release.

“You’re just scared,” Martha said as she offered her outstretched arms. “Lie down. I promise I won’t let go.” How light Charlotte felt, buoyed by those strong hands. When she looked up, there was only encouragement in Martha’s face as she began to move Charlotte’s body in a slow circle. When her arms slid away from Charlotte’s belly, it was as if scaffolding fell, and Charlotte could feel the plane of reality shift from vertical to horizontal. She was floating. This was how fish must feel—fish, and birds, and trapeze artists. “Well done!” Martha said when Charlotte managed to blow bubbles. In a maternal gesture, she removed a strand of hair from Charlotte’s mouth. “We really need to get you a cap.”

Charlotte allowed Martha to take her hands and tow her, kicking, around the dock. When they stood, Martha slipped her fingers under the strap of Charlotte’s bathing suit, and pulled her near. Charlotte had a vivid experience of Martha’s body then. It came like an eddy pooling around her. Martha’s lips brushed Charlotte’s mouth and returned again, this time the tip of her tongue rousing Charlotte from her stunned disbelief. She jerked her head back. “What are you doing?”

“I’m sorry. Did I misunderstand?”

“Misunderstand?”

Martha stepped back. “It’s just the way you kept looking at me.”

“I don’t know what you mean.”

“Look, I didn’t mean to spook you. I thought…”

Charlotte could feel her heart pound against her back. “I have to get back.” She sloshed toward the beach. Mud and dry leaves accumulated on her feet. The earth radiated heat. But Martha wasn’t finished, calling something Charlotte couldn’t make out. Charlotte had the odd thought that English was not Martha’s first language and that this confusion was simply something of the clumsiness that came with translation. She almost turned to wave goodbye, but afraid of unintended communications, thought better of it.

“Wait,” Martha shouted, rushing to catch up. “Charlotte, can I talk to you?”

Martha was standing so close it felt to Charlotte as if she was about to single-handedly gang up on her. “I won’t tell—if that’s what you want,” Charlotte said.

“No, not that,” said Martha, staring intently into her face. “Can I give you some advice? Take a look in the mirror sometime. You were truly giving me looks.”

Charlotte moved quickly to pick up her towel and her beach bag. She knew Martha was watching her and she felt completely exposed. The skirt of her bathing suit clung to her behind. Water dripped down the length of her legs, and wetness turned cold in the air. Take a look in the mirror? That Martha saw something she couldn’t made Charlotte panicky, for what was that thing?

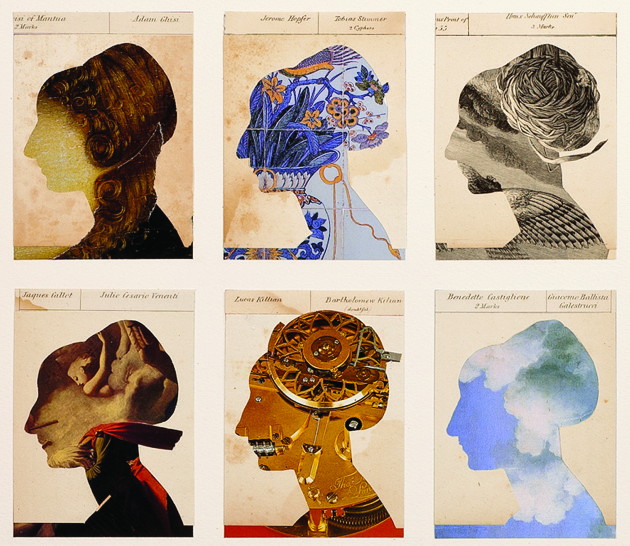

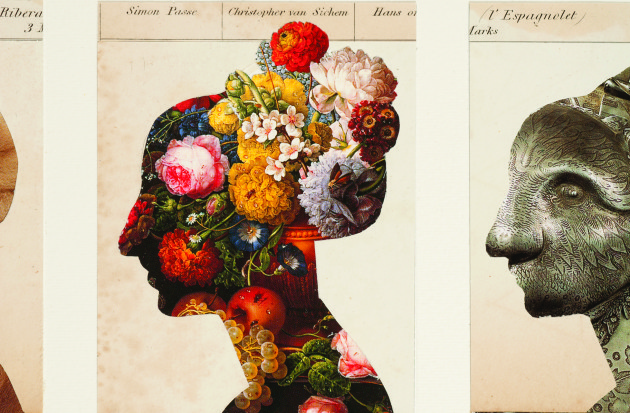

“Mood Swings #2” (detail) by David Barnett, davidbarnettworks.com.

She was still searching for it now as she followed J. Rothenburg. He walked like a horse pulling a millstone, past a grand piano not visible from the front door. It was piled high with travel journals and materials on the occult arts. Its lid was open and the ivory keys were stained. Charlotte had underestimated the depth of the store and the rooms leading to more rooms. Alert to the fact she could be foolishly following a stranger into his lair, she studied J. Rothenburg more closely. His back was curved. His belt was cinched around his ribs. His big, lumpy hands hung at his sides. If there were danger here, it would not come from him. A half-open door revealed a bathroom yellow with neglect, toilet seat up, looking like it belonged in a subway station, and pricking her with the feeling she was here to research filth.

J. Rothenburg stopped in front of a locked cabinet. Screwing up one eye and turning to look at Charlotte as if still debating her bona fides, he finally pulled a heavy keyring out of his pocket and opened the door. “This is the curiosa section.”

The cabinet was filled with forbidden volumes—Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Henry Miller, The Kama Sutra, Marquis de Sade, other French titles she didn’t recognize, and boxes of postcards Charlotte was sure she didn’t want to see. He ran his hand along the red-and-gold bindings of Studies in the Psychology of Sex. There were seven volumes. “That’s what I’m looking for,” said Charlotte.

“A beautiful edition,” said J. Rothenburg.

“How much are they?” She had about three dollars in her pocket. Surely that was not enough.

“Seventeen,” he said.

“Seventeen dollars?”

The look he gave her seemed to say no refunds, no returns and most definitely no bargains.

“Could I buy just one?”

“It’s a set in fine condition, not a spot on it. Plus I have to make it worth my while. I could get locked out of my store, the whole business down the drain. Someone’s going to come in one day, a rich doctor, maybe, and buy the whole set. Who’s going to want six volumes?”

A rich doctor? Taking another look around this faded, melancholy place, Charlotte thought this a gross case of wishful thinking, but J. Rothenburg wouldn’t reconsider. He became decidedly less friendly, or at least less talkative, and looked at Charlotte like he smelled bad faith. He closed the door and turned the key. The metallic clack of the lock was so absolute and final, Charlotte felt as if she were being cast into the street. She made her way toward the door, trying not to feel defeated. She hadn’t imagined the book would be the size of the Encyclopedia Britannica. Where would she hide such a thing in the cramped one-bedroom apartment she and Perry and their four-year-old son, Julian, shared with her mother? But the thought of emerging into the hot air and shimmer of asphalt as ignorant as she’d been when she came was unbearable. She walked back. “Do you think I could just read it for a while?”

“Here? This isn’t a library, miss,” he said.

“I’ll wear my gloves,” she promised.

Perhaps it was her sincerity, or her persistence, or the fact that she had nothing but wearing gloves to offer, but J. Rothenburg softened. He unlocked the door of the curiosa section again. Charlotte pointed to Volume II of the Studies, the volume titled Inversion. She sat where she was told to sit, at the piano. J. Rothenburg closed the lid, placed the book there, and left her alone. The only sound was the ticking of the clock and the creak of the tin ceiling as someone crossed the floor above.

Intending to take notes, Charlotte removed a pad and pencil from her purse. If the doctor were to reveal a path to a cure, she would want to remember it. She ran her bare hand over the pebbled binding and shivered. She put on her white gloves, grateful for the barrier between her skin and Studies in the Psychology of Sex. The cover, scarcely touched, creaked when she opened it. In the preface, the doctor seemed to be making the case for more scientific study and more tolerance of inversion: “Sexual instinct turned by inborn constitutional abnormality toward persons of the same sex.” Inversion.

Through the keyhole of her imagination, the women in the case studies took on life. They all had a tendency to eccentricity or nervous diseases. She read with intense interest about Miss A., aged 38, with her good general health and coolness to men, who came from a family of “marked neuropathic element.” Ellis described her “exemplary” self-control in using her impulses as a “stepping stone to high mental and spiritual attainments.” What did that mean? And how could she, Charlotte Silver, muster similar self-control while haunted by memories of the slightly knock-kneed gait that made Martha’s wide hips sway in a movement entirely necessary and provocative at the same time? Martha’s hips, like her smile had said I know a lot more than you do. Martha’s little acorn earrings, souvenirs from a European adventure, and her stories of drinking and dancing in low-lit establishments in Greenwich Village, hinted of life lived large and was seductive beyond all measure.

Charlotte read on, scouring the section titled “Offspring,” for some insight into how she might protect her son from the consequences of her actions. The new nightmares, the tears of fury—would this have happened anyway? Was there a way to ease his mind? Dr. Ellis seemed to indicate Julian’s predicament would have been much worse if she were a degenerate, or had an early experience that turned her into a habitual fetishist or masochist, and she was not that. He wrote, “Unstable marriages were not beneficial for children.” It was no news to her that children knew things their parents didn’t tell them, and that their hearts could be broken.

She put her pen and pad aside. She couldn’t write Ellis’s words. His tone was clinical and benevolent, but the pages became hostile things, as the words “aberration,” “abnormality,” and “neurosis” proliferated. He wrote about women with abnormally large genitalia who had a preference for oral stimulation, as extreme, unashamed Sapphists. Charlotte turned the page to see a pen and ink illustration of what Ellis called cunnilictus. Her body ached. She was unable to look away as she remembered the very specific hum on her skin when Martha was near. But oh, the nights on the lakeshore, running her hands over Martha’s body, feeling the curve of her spine, the tender muscle, the soft declivities and dark spaces that even now made her mouth dry with desire. Charlotte felt pressure in parts of her body only Havelock Ellis would name. She was “aroused,” a word spread generously throughout Volume II like breadcrumbs leading her to the forest primeval, and she couldn’t help herself. She rocked back and forth on the bench, something Miss M., aged 30, might do, until her mind filled with an intense memory of the pressure of Martha’s little acorn earring against her cheek, and she had an orgasm, a little private one, with her eyes squeezed shut and her chin tucked to her chest. And why not? This summer something free-floating inside her had surfaced and broken apart. It didn’t seem there was much she could do to revert back to the normal girl she used to be. Havelock Ellis, she realized, had done nothing to make her feel less lonely.

Charlotte closed the book. She smoothed her gloves and straightened her hat.

Abandoning any pretense of boldness, she hoped against hope not to encounter J. Rothenburg as she walked, head down, to the front of the store. She hoped so fervently that when he spoke to her it was as if she encountered him with no preparation at all. Charlotte was shocked, but she didn’t think she had recoiled visibly.

“Did you find what you were looking for?” he asked. She looked at him sitting at his desk with his napkin tucked into his collar, and a half-eaten corned beef sandwich and pickles on the wax paper spread in front of him. She forced herself to regroup. She would never see J. Rothenburg again. Did you find what you were looking for? She reminded herself that this was a shopkeeper’s question and not a philosophical one. She hadn’t been truthful with him, and she didn’t have to start now.

Harriet Goldman’s work has appeared in numerous journals including Confrontation and Kalliope. This story is an excerpt from a novel-in-progress set in the 1940s about forbidden love and women who face impossible choices.

Please wait...

Please wait...