by Susan Weidman Schneider

Transgender Jews

An introduction

When Rachel Pollack was four, she knew she was a girl. Like other girls her age, she liked wearing her sister’s clothes and imagining herself as her father’s “darling.” Only . . . Rachel was a son to her loving Orthodox parents and to the outside world. A regular boy. No one knew about her secret—core—identity as a girl, nor about the fantasies, the furtive opportunities for cross-dressing, and the powerful desire to be acknowledged as a female.

Through all the milestones of latency and adolescence, no one knew about the confusion roiling the cowboys-and-Indians-playing kid, the religious bar mitzvah boy who put on t’fillin to pray, and later, the non-dating high-schooler.

At 25, Rachel “came out” as a woman to her female partner, to her students at SUNY Plattsburgh, to her parents and their close community in Poughkeepsie, New York.

At 31, living in Amsterdam, she had the surgery that brought her body into consonance with her gender identity.

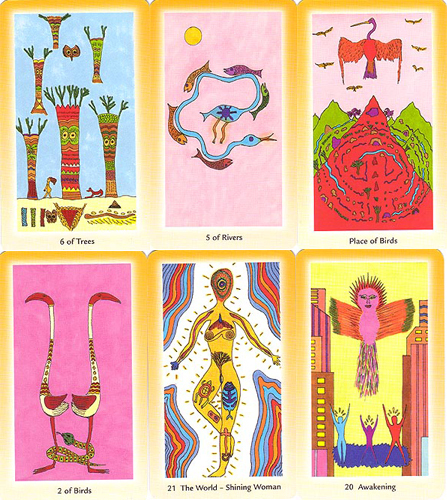

At 45, back in the U.S., an award-winning novelist and author of comic books and Tarot decks, she celebrated her bat mitzvah in Woodstock, New York. For her hand-painted bat mitzvah tallit, Pollack used the ateret, the collar-binding with the prayer embroidered on it, from the bar mitzvah tallit she’d worn decades earlier. (Amazingly, after she removed the ateret from her old tallit, she saw that it had another prayer-strip underneath it, almost as if there had been an extra lying in wait for her all those years: one complete tallit for being a male, one for being female.)

“A girl or a boy?” is the first question you ask when a baby is born. Most of us think of ourselves as ineluctably either male or female, and we usually expect the answer to remain the same throughout our lives.

But it’s not so for everyone. For a variety of reasons, some people feel themselves—in the deepest core of their being—to be born into the wrong presenting body. They may have the physical markers labeled “female,” for example, but feel themselves to female. Or they may have been born with ambiguous genitals (intersex), a condition often altered by surgery early in life.

Transgendered people (the term includes those living as another gender from the one they were born into as well as transsexuals, those who have altered their gender physically in some way) are now a presence on the identity spectrum, and in Jewish life as well. “We used to refer just to gay and lesbian,” says Mark Pelavin of Washington’s Religious Action Center, which addresses a wide range of human rights issues. “Now we add ‘transgender’ too.” Kolot, The Center for Women’s and Gender Studies at the Reconstructionist Rabbinical College in Philadelphia, includes transgender as a subject on this year’s curriculum. Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, the training seminary for Reform rabbis, held a day-long session on transgender Jews for its New York students this winter. And the 92nd Street Y summer community service trip for Jewish high schoolers—Tiyul—has participants spend an evening in discussion with a transgendered person, so the teens can understand “that all people deserve love and caring and advocacy,” says the director of the Y’s teen programs, Sharon Goldman.

Alyson Meiselman, 51, a Maryland attorney, now specializes in gender law. Meiselman became a woman at 47. “As a kid, I always wanted to wake up one morning and be female,” she says. “I had cross-dressed always—but that was symptomatic. A transsexual person doesn’t cross-dress for sexual gratification. It’s more like a sedative; it makes you feel calm.” Meiselman, who grew up in a traditional Conservative family, remembers as a USYer helping dry out books after the Jewish Theological Seminary fire in 1967. She’s still active in a Washington-area synagogue, and a former rabbi of hers appears in a television documentary about her transition “saying, basically, that the person is changing their body, not changing their mind.”

Not everyone is so supportive. Amy Bloom, in her forth coming book Normal, says, “A great many people, sick of news from the margins, worn out by the sand shifting beneath their assumptions, like to imagine Nature as a sweet, simple voice. Bloom, whose 1994 New Yorker report on female-to-male transsexuals broke new ground, continues,”[0]ur mistake is thinking that the wide range of humanity represents aberration when in fact it represents just what it is: range. Nature is not two little notes on a child’s flute; Nature is more like Aretha Franklin: vast, magnificent, capricious—occasionally hilarious—and infinitely varied.”

Today there are examples aplenty of this gender variety, both in popular culture and in the law. The New York Times Magazine features a transsexual couple on its cover; Michigan State University debates creating a transgender bathroom, and all-women Smith College rules that no student can go on male hormones while enrolled. The Today Show reports a Kansas City court may decide that a widow cannot inherit her husband’s estate because she was born a man, and the Times covers the case of a transgendered man in court in Florida trying to gain custody over his children.

Though demographers don’t know the actual number of people who have transitioned from one gender to another, whether through surgery, hormones, or a choice to live as the “opposite” sex without physical alteration, clearly, this is a moment in the Zeitgeist when “transgender” is on our radar screen. And Jewish transgendered people are beginning to go public with their experiences. Margaret Rothman, coordinator of gay, lesbian, bisexual and transgender services at San Francisco’s Jewish Family and Children Services, says “Half of my GLBT speakers bureau is transgender—they’re dying to talk.” Although they represent a tiny minority, Jews crossing gender boundaries are becoming increasingly vocal.

What do we possibly learn from them? Hebrew Union College rabbinical, cantorial and education students have begun to find out. A “Pluralism and Tolerance” program addressed “the challenging question of the religious, legal and policy issues arising over gender identity.” Joining the students and faculty members were a rabbi, a legal expert and a transgender person discussing law, Jewish tradition and “the intense personal feelings that underlie this issue.” The point, says Dean Aaron Panken, was “not to make policy or public statements, but rather to inform our students of the possible presence of such individuals in their congregations and organizations, helping them to respond with sensitivity to the human beings involved.”

Many transgender Jews feel very strongly about finding their place in the Jewish community and spiritual solace in Judaism. Rabbi Margaret Moers Wenig, who organized the HUC symposium, comments that this devotion exists despite the fact that the strictest interpretation of Jewish law forbids transsexual surgery. (“Sex change operations involving the surgical removal of sexual organs are clearly forbidden on the basis of explicit Biblical prohibition,” writes Rabbi J. David Bleich).

Rabbi Wenig concluded the symposium at HUC-JIR:

Anne Fausto-Sterling, an embryologist at Brown University, has argued that there are not two but five sexes, in addition to male and female. She introduced the terms: “herms” (true hermaphrodites, born with a testis and an ovary), “merms” (born with testes and someaspect of female genitalia) and “ferms” (born with ovaries and some aspect of male genitalia).

“Male and female God created them?” I believe this verse is an example of the figure of speech called “merism” in which a totality is expressed by two contrasting parts (e.g. “young and old,” “thick and thin,” “near and far.”) In other words: “Zachar u’nikeva bara otam.” “God created male and female and every combination in between.”

So. . . Is someone who is inter sex a man, or a woman, for purposes of gender-specific Jewish ritual? (Mishnah Bikkurim 4:1-5) Should a transgendered woman be welcomed into a Rosh Hodesh group? Can a transgendered man be counted in an Orthodox minyan? If one has “transitioned” from female to male with surgery (FtM, in shorthand), is it necessary to have a brit milah, a ritual circumcision, to be considered a Jewish man? And despite the fact that Jewish law, in its strictest interpretation, forbids mutilation of genitals (circumcision excepted), what is a compassionate way to help a Jew live as her or his true self?

We ask because the questions themselves—as you will see from the following pages—may teach us some things about gender and about Judaism. It’s surprising—and refreshing—to note that some of these questions were considered centuries ago by the rabbis who encoded Jewish law and practice; nothing human was alien to them (Bereishit Rabbah 8:1)

For more resources, click here.

Transgender Jews

The articles in this special section:

Gender in Genesis

by Gwynn Kessler

Bet you didn’t know… what the Talmud says about Gender Ambiguity

by Alana Suskin

"It is unsurprising that rabbinic law treats the male as the norm and the female, by definition, as an anomaly—a deviation from the norm. Still, the sages do perceive women as human beings, creatures similar to men in important ways. Women are both 'like' and 'not like' men."

In The Image of God

by Danya Ruttenberg

Shul Matters

by Micah Bazant

“Today I am a Man” Takes on New Meaning

by Danya Ruttenberg

Please wait...

Please wait...