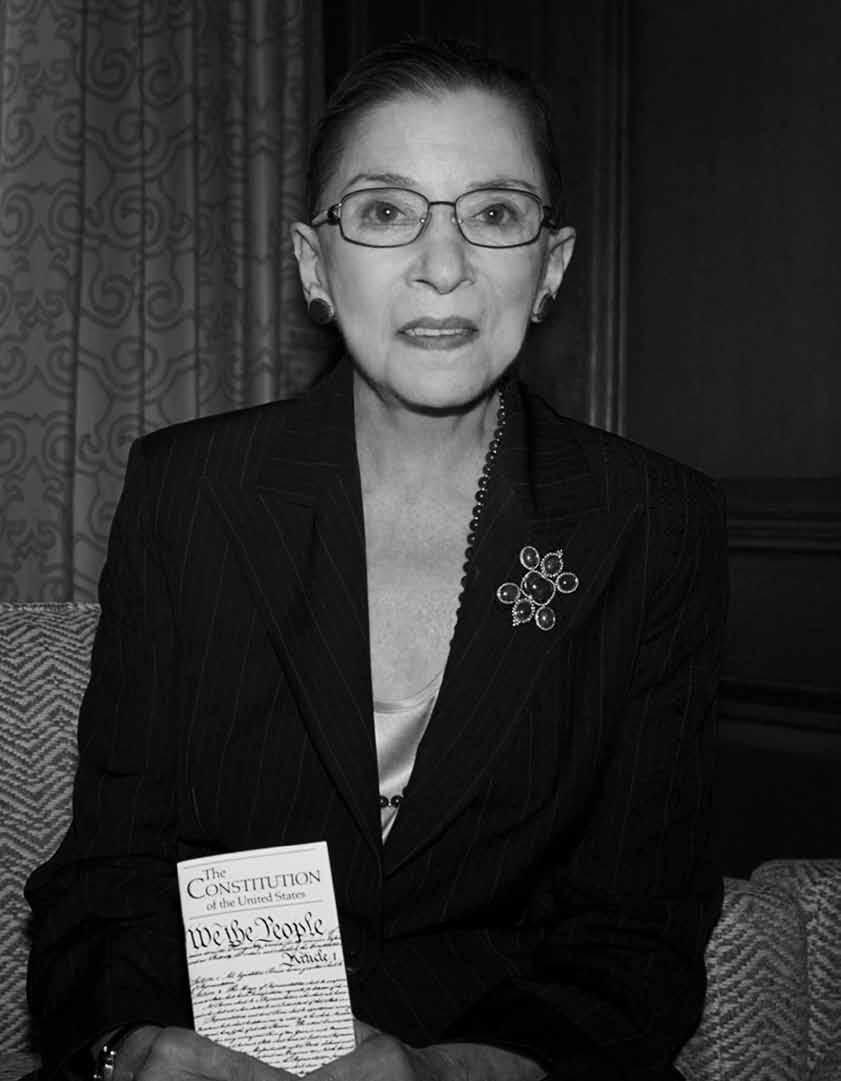

by Joan Roth

An Indispensable Member of the Supremes

Joan Roth visits Ruth Bader Ginsburg in Washington.

Photograph by Joan Roth

The walls of the Supreme Court’s reception room in Washington, D.C., are lined with portraits of the Court’s former chief justices, all powerful white men. This was the formal setting in which I was first told I could photograph Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the court’s first Jewish female justice, named by Forbes magazine as one of the world’s 100 most influential women.

Justice Ginsburg would look great at the center of the room, and I imagined her not on a bench, but on a horse (she rides), twirling a sword (she was a champion high school baton twirler) in her black robe and white lace collar, an American flag around her shoulders, blowing in the wind, bringing to mind the biblical Deborah.

Jewish justices, of course, have been here before. Louis Dembitz Brandeis was the first Jewish justice, appointed in 1916. Brandeis was followed by Benjamin Cardozo, Felix Frankfurter, Arthur Goldberg and Abe Fortas, each filling, consecutively, what became known as “the Jewish seat.” After Fortas resigned in 1969, the court remained without any Jewish justices until 1993, when Ginsburg joined Sandra Day O’Connor as its second woman. When she was nominated, Ginsburg made no overt statement about her ethnic or religious identity. But Ginsburg clearly identifies as a Jew. When the Supreme Court later changed the venue of our photo shoot to the justice’s chambers — my first choice — she asked to be photographed alongside the mezuza given to her by students who’d visited her from the Orthodox Shulamith School for Girls in Brooklyn. “They asked good questions and they really wanted the answers,” she told me.

Ginsburg has said she carries a copy of the Constitution with her. I blurted out, “It’s my favorite document, that and the Torah.” “Only the Torah?” Ginsburg shot right back. “What about the Talmud? What about the Mishnah?” Her quick comeback naming the texts codifying Jewish law certainly indicate the staying power of Ginsburg’s early Jewish education (at the East Midwood Jewish Center in Brooklyn). “I have the good fortune of coming from a culture that prides learning, that thrives on arguing,” Ginsburg told a sell-out audience at New York’s 92St Y in 2008. “I am tremendously fortunate to be part of that heritage.”

Ginsburg certainly knows how to operate. At the Y she told NPR’s Nina Totenberg about advice she’d received on her wedding day: “My mother–in-law and I were alone in the bedroom, and she said, ‘Dear, I would like to give you some advice, it’s the secret of a happy marriage. And it’s simply that every now and then it helps… to be… a… little… deaf.’ I found that advice has stood me in such good stead throughout life, not just in dealing with my dearly beloved spouse, but with my colleagues at the court.”

With Elena Kagan sworn in as the 112th justice this August, there are a historic three women on the court, and this may be a tipping point. We know from studies of how boards work that when one-third of a decision-making body is female there’s an opportunity for significant gender progress on any issue the board addresses.

While I was photographing, Ginsburg told the information officer accompanying us that she has no plans to retire soon, that she intends to stay on the court at least as long as Brandeis did. (He served for 20 years to Ginsburg’s current 17.) Good news for all of us. As Michelle Goldberg wrote in the Daily Beast recently, “For feminists she is irreplaceable. She needs to stick around as long as she can.”

Please wait...

Please wait...