Lesléa Newman

Always a Crossword Between Us

Her mother never met a crossword puzzle she couldn’t solve. After her death, the author continues the tradition, making more headway on Mondays than on Saturdays.

On a recent Sunday morning I sat at the kitchen table in my fluffy white bathrobe, sipping a cup of hazelnut coffee and tapping one polished red fingernail against a wooden pencil. The New York Times crossword puzzle was spread out before me, and as I searched my brain for a four letter word meaning “gradually give up” a realization struck me.

I have become my mother.

My mother never met a crossword puzzle she couldn’t solve. She did the New York Times puzzle every day, scoffing at Mondays which were so easy she found them personally insulting (“You call this a puzzle?”) and delighting in the challenge of a Saturday puzzle which might take all afternoon. My mother was many things, but she was not a quitter. (When asked the secret to the success of her 63-year marriage she gave a one-word answer: perseverance.) Every time my mother finished the puzzle — and she always finished the puzzle — she crowed “Ta-dah!” cast the paper aside, and slapped her pencil down on the coffee table with a loud, triumphant smack.

When did my mother start doing the crossword puzzle? When she was a high school student? A sales clerk at Orbach’s? A young bride? A new mother? I’ll never know. That’s one of the many things I never got to ask her.

When the Sunday papers were delivered to my childhood home back in the day before pieces of the Times arrived on Saturday, it was cause for celebration. Sections were passed out like presents: my father handed the Sports section to my older brother, gave me the Book Review, offered the funnies from Newsday to my younger brother, put aside the Business Section for himself, and bowing like an English butler, presented the magazine to my mother. She would be sitting in the den dressed in her fuzzy green housecoat with a cup of instant Maxwell House coffee in a mug marked “The Boss” steaming to her left and a nonfiltered Chesterfield King cigarette in an ashtray shaped like an upturned palm smoldering to her right. Once she had the magazine in hand, she put down her half-eaten bagel, picked up a newly sharpened pencil, and began filling in the little white squares. The room was silent except for the occasional turning of a page like a sigh, and the click-click-click of the tip of my mother’s red-polished nail tapping the side of her number two pencil, which she said helped her think.

My mother was smart. Final-Jeopardy smart. Use-all-seven-tiles-and-get-fifty-extra-points Scrabble smart. She could tell you who won the Oscar for Best Actress in 1939 (Bette Davis for her role in Jezebel). She could tell you the state capitol with the smallest population (Montpelier, VT). She could tell you a girl’s name that means fighter (Gertrude). My mother knew everything. Well, almost everything. Once in a while an answer eluded her. Usually it had to do with sports. When that happened she’d look over the rim of her leopard-print reading glasses and point her pencil at my older brother. “Who won the World Series in 1959?” she’d ask. “Dodgers,” he’d reply without looking up. Sometimes a clue regarding the law stumped her. “Dear,” she’d say to get my father’s attention. “Who was the only Chief Justice of the Supreme Court from Kentucky?”

“Kentucky?” my father asked as though it were a foreign country he’d never heard of. “Kentucky….” he mulled the word over, stalling for time. “Wait a minute. It’s coming to me. Oh, that was….you know… what’s-his-name…”

“Six letters,” my mother prompted. “Begins with a V, ends with an N.”

“Vinson!” my father cried. “Fred Vinson.”

“You are correct,” my mother said, and filled the letters in.

When my mother got sick, we started doing the crossword puzzle together. Every morning, after she rose from the hospital bed we’d set up in the den and settled onto her rust-colored recliner with a cup of tea and a piece of dry toast beside her, I handed her the puzzle. She filled in as many answers as she could and then passed the paper to me. “You try it for a while,” she’d say. “I’m tired. I’m going to rest my eyes.” If it were a Monday or a Tuesday, I usually did well, but if was any later in the week, I’d have a difficult time. “Mom,” I said one morning, “what’s a 9-letter word for ‘lily-livered’?”

“Lily-livered?” My mother’s eyes snapped open as her voice rose in delight at the challenge. “Cowardly?”

“Too short.”

“Frightened?”

“Too long.”

My mother shut her eyes again and I could see that she was counting letters in he head. “Spineless,” she declared with confidence, already knowing she was right.

As my mother grew weaker and our trips to the hospital became more frequent, I began to measure her state of being by how well she did the puzzle. If she couldn’t tell what a trypanophobe fears (“needles”) I knew she was having a bad day. If she couldn’t tell me an eight-letter word meaning short-lived (“fleeting”) I knew she was having a very bad day. And if she told me to just do the puzzle myself, it was all I could do to not break down completely. But being a good daughter, I did what my mother told me, struggling to think of a seven-letter word for depart (“abandon”), a six-letter word for radiologist (“imager”); a five-letter word that meant be overwhelmed (“drown”). Sometimes the clues were downright scary: Where to find some very sick individuals (“ICU”). Sign between Gemini and Leo (“Cancer”). Waif (“orphan”). Trounced (“defeated”). End (“finis”).

And then, as it always does, the end/finis came all too soon. My mother departed from this earth, abandoning my brothers, my father, and me on a Wednesday. The next few days passed by in a blur: we wrote my mother’s obituary, held her funeral, sat shiva, and tried in vain to make a dent in the fruit baskets and deli platters that kept appearing on our doorstep. After about a week, the house became quiet. Too quiet. I looked around and saw a pile of newspapers on the coffee table. I offered my father the Business Section which he took. Then he said, “Why don’t you do the puzzle?”

I glanced at the magazine section but couldn’t even bring myself to open it. “I can’t,” I said.

“You have to,” he lowered the paper. “Your mother would want you to.”

“But I’m not as smart as she is.” I couldn’t bear to speak of my mother in the past tense.

“No one is as smart as your mother,” my father reminded me. “But you have to try.”

And now it is THREE years later and I am still trying. I am sitting in my own kitchen, with the puzzle spread out before me. My coffee has grown cold. My pencil has grown dull. My leopard-print glasses have slid down my nose. “Gradually give up,” I read the clue to 34-across aloud. Tap tap tap goes my red nail against the wooden pencil. “Wean!” It comes to me in a flash and as I fill in the letters, I hear my mother’s voice in my head say, “Good girl.” I put my pencil down and stare out the window. “Mom, where are you?” I whisper. “I don’t know how to do this.” By “this” I don’t mean the puzzle. I can struggle through the puzzle. I’m getting better. Like my mother, I now consider Monday crosswords an insult, though I still don’t make much headway on Fridays or Saturdays. No, what I can’t puzzle out is how to be a motherless daughter. How in the world am I supposed to live the rest of my life without my mom?

I haven’t got a clue.

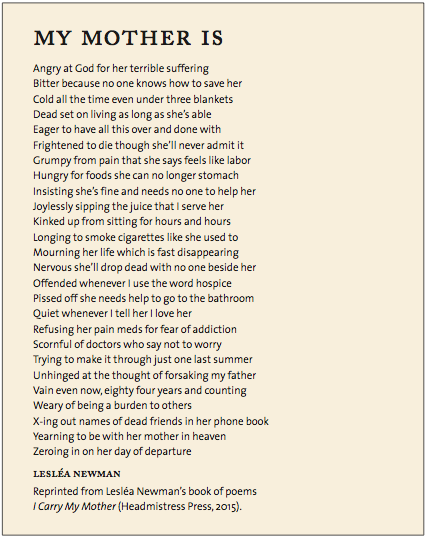

Lesléa Newman’s most recent book is the poetry collection I Carry My Mother. On January 16, 2007, she appeared in the New York Times crossword puzzle as the clue for 32 across: “With 42 across, Lesléa Newman book.” (Answer: Heather Has Two Mommies.)

Please wait...

Please wait...