Judy Gerstel

A Canadian Feminist Publisher Known for Kids’ Holocaust Books

Who would have thought that children’s books about the Holocaust would become popular with kids?

Who would have thought that children’s books about the Holocaust would become popular with kids?

The Holocaust Remembrance Series for Young Readers, from Second Story Press in Toronto, now has more than two million copies in print and is available in 51 countries and 39 languages. Though the series started with only one such book, publisher Margie Wolfe never doubted the value and importance of “having that literature available to children as they were growing up. The challenge was to take a difficult or problematic subject and make it work for kids. And that’s what we figured out.”

But even Wolfe was surprised at what followed.

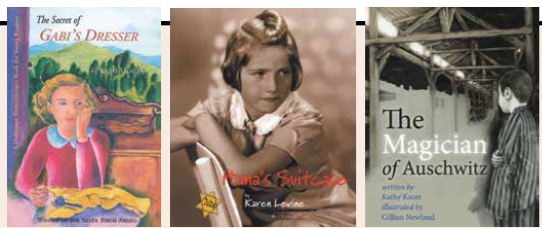

“We always assumed the first one would be a one-o ,” she says. The Secret of Gabi’s Dresser, intended for 9- to 12-year olds, was published 20 years ago. “It’s based on the true story of a child, the author’s mother, in Czechoslovakia. When the Nazis came to collect Jewish girls, she was hidden in a dining room dresser and was saved.” Wolfe recalls, “My sales reps, who are commercial sales reps, thought they’d humor me. ‘Oh, Margie wants to do this, we’ll sell it to a few Jewish bookstores and that will be the end of it’.” But it was only the beginning.

Gabi started garnering kudos, including the Ontario Library Association’s Silver Birch Award. “That was an important moment for us,” explains Wolfe. “There’s a short list chosen by librarians, and then the kids vote. The kids had an opportunity to decide on something fun and easy, but they didn’t. They chose this true story about a child in war whom they could empathize with and cheer for and su er with.”

The author of Gabi, Kathy Kacer, wrote more award-winning books for the series. And then, said Margie, “there was our ‘miracle book’: Hana’s Suitcase,” published in 2002. This is a true story about a woman who travelled from Japan to Canada to meet the brother of a child killed in the Holocaust. Hana’s Suitcase is Canada’s most honored children’s book, ever. It has been translated into dozens of languages, and is still popular and still winning awards around the world.

But what is most important to Wolfe is that “it revolutionized what it was possible to tell kids at a young age.

“I always knew that you could. I just didn’t know how to do it. And then I realized that what we had to do was to tell a story. With Hana, we are telling a mystery, an adventure story.” Years ago, she says, someone from Yad Vashem, Israel’s official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust, approached her, saying, “We do Holocaust books for children. How come yours are more successful?” Her response: “They publish research. We publish stories. The challenge with each one is to create the most compelling narrative without sacrificing content.”

The problem presented by this kind of writing for children was taken up recently by Ruth Franklin in The New Yorker, in “How Should Children’s Books Deal with the Holocaust?”

“Most children today will never see a survivor’s tattooed arm,” wrote Franklin. “Those of us who did are likely trying to figure out how to approach the Holocaust with our own children, wanting them to recognize its significance in their family history without allowing that knowledge to burden or define them. Still, to me, there’s something essential about the interactions among generations in the stories we tell about the Holocaust.”

The most risky title in the Second Story Press series, Wolfe acknowledges, is The Magician of Auschwitz, also by Kathy Kacer. “I knew with the title that we were taking a huge chance,” says Wolfe. “But it also won the [Silver Birch] children’s choice award. When kids 8 to 12 were given a selection of books to read,” she says with a degree of wonderment, “they voted for a book called The Magician of Auschwitz.”

Second Story Press has become a magnet for writers from all over the world who want to submit Holocaust books for children. Wolfe is very clear about what she will publish. For example, she flatly rejects pitches where the characters are rep- resented by animals.

“We won’t do them,” she insists. “We want kids to know these are real stories, not some fantasy about animals, that the ones who suffered were people.”

And because the books are translated into German and Eastern European languages, she makes sure there’s nothing in them to make “kids in those countries feel responsible for what happened decades and decades ago. We don’t say German soldiers. We say Nazis.” She explains: “We want the readership to be mostly non-Jewish, and 95 per cent are not Jewish. That’s the goal—to have those children read the books and to know that his- tory, to say how awful, but not to feel responsible for that history.”

That history is also Margie Wolfe’s history. She was born to survivors in the displaced persons camp at Bergen-Belsen, and came to Toronto as a very young child. Her rst job was with The Women’s Press in Toronto, and she’s proud of being a feminist publisher for the last 40 years.

She founded Second Story—the official name is Second Story Feminist Press—with three other women; she later bought them out.

“Anything I do is informed by feminism,” she explains. “It’s what I bring to whatever kind of book that we do.” Her list includes fiction, nonfiction and biography for children and adults. A book she describes as “Thelma and Louise but better, about two women with mild Alzheimer’s” who find an offbeat way to maintain their independence, won Canada’s prestigious Leacock award for humor.

And then there’s a Gutsy Girl Series, and I’m A Great Little Kid picture book series for ages 5 to 8, a mystery series for teens, a First Nations Series for Young Readers, focusing on indigenous peoples in North America, which has garnered many awards and is popular in U.S. school libraries, and even a children’s book about euthanasia. New releases this year include Black Women Who Dared, for children 9 to 13, The Story of My Face, about a girl scarred by a grizzly bear attack, recommended for ages 13 to 17, and a novel for adults about two Winnipeg sisters haunted by their childhood in Russia.

But for all the eclecticism in the lineup, Second Story sticks to its mandate to publish books by Canadian authors that pro- mote feminism, social justice and Judaica.

“We did the first collection of Yiddish women writers in translation back in 1995,” Wolfe notes.

Perhaps most amazing—and testimony to Margie Wolfe’s shrewdness as a publisher—is that, even with her strict mandate, Second Story Press manages to turn a small pro t, albeit with some government grants, available to all Canadian publishers who meet certain criteria. “We have been a pro table company for 20 years,” she says. “Our biggest level of sales was last year and this year will likely be even bigger. I think that has some- thing to do with what’s going on in the world today. When we rst started in 1980, nobody even thought we would last very long. We were on the periphery of real publishing in Canada. Now, there’s no question, and hasn’t been for a long time, about our validity. We operate on a world stage. Some of the largest publishers in the world buy from us: Random House in the U.S., Ravensburg in Germany.”

Wolfe, who is in her late 6os, allows herself one last brag: “Arguably we are the best in the world at doing these books for young children. I’m proud of the quality of the books and the reach they have and the possible impact they have. I like to think that a kid who is caught up in one of the stories will have that in their head for a long time and take it with them and help them know how to behave the next time they have a choice to make that is less or more humane. And that is the main reason we want the readership to be not just Jewish kids.”

In effect, the mandate and output of Second Story Press is Wolfe’s own raison d’être. “It’s my activism,” she says. “I spent my time like everybody else at millions of demonstrations and this is what I have to contribute, as a woman, a feminist, even as a Jew. This is my contribution and my legacy.”

JUDY GERSTEL is a Toronto-based freelance journalist, formerly a critic and editor at the Detroit Free Press and Toronto Star.

Please wait...

Please wait...