by Shira Sternberg and Susan Schnur

Say Yes to the Dress

Who Says You Need a Groom (or a Bride)?

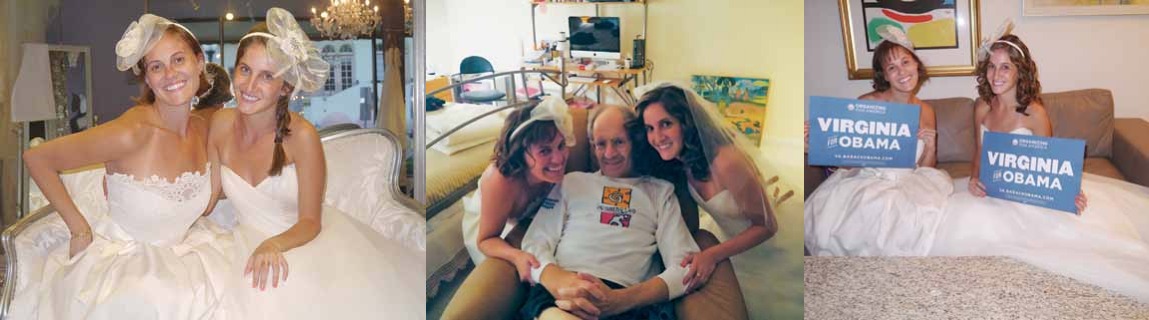

- Shira Sternberg (short dress and short hair), and her sister, Tava Sternberg (long dress and long

hair) and their father, Rolf Sternberg.

On october 5, 2011, I got a text from my father. He was at home in Shaftsbury, Vermont: “Please call me when you can.”

I knew it wasn’t good. He’d had three 911 “episodes” in the previous four months — lightheadedness, fainting, stuff that just felt foreboding — and I’d been, well…kind of waiting.

I was in a work meeting in D.C., and immediately stepped out.

“Hi, Daddy,” I whispered tentatively.

“Shira,” he said, instead of the usual “SHIRA!!!” — letting the whole world know that talking to one of his daughters was the greatest part of his day, week, month, year, life. He was crying and could barely speak. “I had some tests done, they are still waiting for the results, but they think I have c…, ca…, can….. “ He couldn’t say the word.

For him, it was the worst possible diagnosis, since he’d taken care of my mother for 16 years (since I was four, and my sister Tava was an infant), helping her endure treatment after treatment for breast cancer, and he’d developed a scrupulous anticancer “religion” to protect himself from anything that might resemble her fate. He ran a precise distance every day; he never drank, never smoked; he eschewed all red meat and most dairy; and he followed a ritualized daily diet, which everyone who knew him made good-natured fun of: his dinners, for example, were steamed broccoli and mashed potatoes — the latter consisting of a potato mashed with itself.

He and my mother, both lawyers, had become very knowledgeable and active in the cancer prevention world; she helped found the National Breast Cancer Coalition with Fran Visco.

“I’ll be on the first flight home,” I said. My sister Tava, in graduate school for dietetics in Boston, also headed home. At least we’d all be together. By March 2012, I had relocated to Boston, and Tava and I spent every weekend in Vermont. That May I ran my first marathon. On some level, illness, death, and the genetically transmitted BRCA gene had made our family into one organism: we each did what we could to stay healthy.

My father had always taken issue with some mainstream (Western) medical practices, and he decided to participate in a holistic cancer-treatment program in Longboat Key, Florida. I visited him there in April and saw that his health was deteriorating. He didn’t acknowledge that he was dying, but he was. Of esophageal cancer.

In June, he came back to Vermont, saying that he loved New England summers (that’s true) and that he needed to oversee some house renovations — a new bathroom for me, and a roof that was supposed to last 50 (instead of the usual 20) years. In retrospect, it’s clear that Dad was just “prepping” the house for us; he didn’t want to leave his daughters with a place full of problems. In mid-July, he went back to Florida.

It was mid-September — I was at a friend’s wedding in D.C. — when I got a frantic call from Tava. Dad had a doctor’s appointment the next day, and according to a close family friend, “it would be best if [I] were there for it.” I called Dad, but he poo-pooed the urgency. Then he cried. I left the wedding and went straight to the airport.

The next morning I told Tava that now was the time to take the semester off from school; Dad didn’t have much longer. She was with us for a full week in Longboat Key before she mustered up the courage to tell Dad that she’d un-enrolled for the entire semester.

“What?” he said, in disbelief, looking up at us with sweet, childish eyes. “I took the whole semester off, Daddy,” she repeated.

“Well,” he said with resolve, “I better get well really fast.”

Mid-October ushered in one killer day after another. October 13 was the first day that Dad no longer had the strength to leave the house. On October 15, I turned 30 (Mom had died when I was 20). On October 16, I got the results of my own BRCA gene testing. Like Mom, I was positive. (Tava has since tested negative.) The gene is known to increase one’s risk of developing breast and ovarian cancer, though there is no data on how much regular exercise and a healthy lifestyle can shift those numbers. I told Dad the results of my test, and he advised me not to undergo preventive mastectomies. Overall, it felt like there was just too much grief and fear to process, and that our hearts and heads couldn’t work fast enough.

On October 17, my sister and I took our daily, hallowed car trip to Whole Foods. Though Dad wasn’t eating, he had hourly requests for new weird items: bacon, tapioca pudding, Thai soup. The trips were important for us; Dad wouldn’t let us talk about the fact that he was dying in his presence.

“It’s my job to get better” is all that he would say — he couldn’t tolerate knowing that he, like Mom, was doing something that only a bad parent does: die prematurely. He remained firmly in denial. In the car, Tava and I had truthful moments of planning for Dad’s death and memorial service, and our sisterly sharing buoyed up how lonely this all was, making us close.

As usual, we passed La Mariée, the local bridal shop — a place we’d passed dozens of times — but this time, for some reason, I burst into wracking sobs.

“Dad won’t know the man who becomes my husband,” I wailed.

“Get it together,” Tava said. “Shira, you have to get it together.”

“But I was supposed to have a baby before I turned 30; it decreases your risk of getting cancer. I’m 30, Tava, I’m 30!”

“Well, it didn’t happen,” Tava said. “You’ll meet someone, Shira. You’ll have children.”

“I’ll just do it,” I said, sobbing. “I found this person, we’re going to get married. Here’s the plan. I have a guy….”

“Shira,” Tava said, “you said he’s not into you.”

“It doesn’t have to be reciprocal! Everyone’s dead! Mom, Nona, Omi, Opa…. You don’t understand! Dad has to meet my husband, Tava, he has to be at my wedding, he has to be a grandfather to my children!”

Tava had pulled off the road, but she suddenly re-entered traffic and started briskly driving home.

“Wouldn’t it be fun to try on wedding dresses?” she said brightly.

I looked at her. Had my sister gone mad?

Suddenly something clicked.

“Let’s just buy them!,” I said, no longer crying.

“But how will we explain it to Dad?”

“I’ll say, ‘We have this idea, Daddy. For a really nice family thing to do. A photo shoot. It’s going to be really special….’”

“He’ll ask how much the dresses cost,” I said. We both started laughing.

“I’ll say, ‘Don’t worry, Dad. They’re on sale.’”

The talk went as we’d expected, and, in a sense, even better.

“I get it,” Dad said with a sigh. And then, heartbreakingly, “Okay.” It was the only time that he, even skirtingly, acknowledged to us that he was dying.

“So how much are they?” he asked.

“It’s a good deal, Dad.”

“Okay,” he said. “But promise me you’ll both get married under a tree.”

Earlier that year my co-worker had gotten married under a tree — it was just herself, her husband and their dog. A robot took the pictures. Dad loved that. He hated extravagant spending, but he loved celebration. He and my mother had had a small outdoor wedding at Bennington College. Mom made her own dress, and the only thing they served was dessert and champagne.

A wedding under a tree sounded good to both Tava and me. And it solved all the problems — who would walk us down the aisle, who would be there for family photos.

“You got it,” we said.

The following day my uncle agreed to stay with Dad so that Tava and I could go shopping. (My aunt had heroically left her work, home, and kids for weeks to be with Dad in Florida, and she was juggling everything electronically; my uncle was spelling her for a few days.) Tava tried on four dresses and I tried on two, but we spent over four hours in the store, playing with hats and poses, props and gloves. Kara — the manager of the store and our new dear friend — took photos, promising to discount the dresses and to come to the house to curl our hair and do makeup. It was epic, one of the most fun times that either Tava or I have had in our lives.

“Are you marrying each other?” a prying customer asked. “Actually,” we answered in unison, “neither one of us is getting married.”

One week later, we realized that we couldn’t wait for the seamstress — Wendy, another new fast friend — to take our dresses in, even though Kara had marked them “priority.” Dad’s health was declining rapidly, so we put on our unaltered dresses, Kara did our hair and makeup, and we set about trying to coax Dad on to the beach for a photo shoot — under a tree.

“I can’t do the beach. I’m not well enough,” he insisted. “I’m saving energy to get better.” It didn’t matter. Kara took two photos of all of us in the house, and we got the proof we wanted: Dad was at our weddings.

Shira, Rolf and Tava Sternberg.

I wore my dress to Barack Obama’s 2012 Inaugural Ball and to my house renovation party in Boston. And I have a priceless dress that I intend to wear not only at my wedding, but for the rest of my life.

Neither the dresses, nor the lives, are the ones that my sister and I would have chosen.

But they’re ours. So, yes. We said yes.

Shira Sternberg now lives in Tel Aviv, where she has developed a jewelry/fashion start-up with her sister Tava. Their business was inspired by their father, who used to give each of them a piece of jewelry every Valentine’s Day. Shira previously worked in politics.

Please wait...

Please wait...