Tag : Sophie Glass

August 28, 2007 by admin

Working Onwards, with Determination and Hope

On Tuesday I will fly to Uganda to spend the fall semester studying and traveling. This new beginning also marks the end of my brief stint as a Lilith Blogger. Throughout the summer, I have tried to expose the genocide in Darfur in two ways: by describing the actual crisis and by highlighting the international community’s response. Overwhelmingly the situation “on the ground” is dire, while the anti-genocide movement is thriving. Clearly, there is a disconnect between the tireless efforts of countless students, adults, celebrities and (some) politicians, and the continued suffering of the Darfurians. Does this mean that the activists should give up? Absolutely not. The anti-genocide activists’ work is valuable even if the immediate goal of stability in Darfur has not been reached yet. Here’s why:

1. The anti-genocide movement that has erupted over the past few years (over 600 STAND: A Student Anti-Genocide Coalition chapters and hundreds of Save Darfur groups) is possibly the first time in history in which ordinary individuals are working together to demand more of their international institutions. From high school students writing letters to the Secretary General of the UN, to average citizens directly funding the African Union peacekeepers, people are expecting more of the multinational organizations that were intended to prevent catastrophes such as genocide from occurring. Our interest in international affairs and global governance signifies that we are being better watchdogs. It is a shame that millions of Darfurians had to suffer for us to open our eyes, but now that they are open who knows what future calamities might be avoided due to our increased vigilence and pressure on international institutions.

2. Never underestimate the importance of the individual. As Robert Winters, the former director of the US Committee for Refugees, said: “People die one at a time, not in millions. We must never forget that. Nor let anyone else. Otherwise, there is the danger of becoming numb to it.” Even if one Darfurian’s life was saved due to our letters and phone calls then our work is not in vain. Additionally, the anti-genocide movement is about human beings reaching out to other human beings, not about “saving” a certain allotment of people. Genocide can only persist when perpetrators cease to view human beings as individuals, and instead see them as part of a larger ethnic, racial or religious order. The attitude that recognizes the importance of the individual challenges the generalizations that allow for discrimination.

3. Rabbi Hillel taught us that when we are faced with inhumanity, our duty is to be humane. We do not have to remedy every tragedy, but we must preserve our compassion and empathy that make us so distinctly human. Even if our efforts are not drastically changing the day-to-day life of Darfurians (the UN-AU force might not hit the ground for months, the Janjawid and Sudanese government continue to terrorize Darfurians), it is essential that we stay tuned and stay involved, lest we concede our personal integrity.

4. In the highly complex 21st century world, we do not yet know how to create lasting social change. The anti-genocide movement is about pulling as many levers as possible, including internet activism, targeted divestment, public rallies, art, music and more. Today’s anti-genocide activists are still learning what works in globalized economies and cross-cultural societies; this knowledge will provide valuable information for other humanitarians, environmentalists, progressives etc.

I enumerated these “silver-linings” to encourage anti-genocide activists to stay committed and not to give in to frustration or compassion fatigue. Yet it is equally important not to be deluded into thinking that we have “succeeded” based on these tangential victories. It is the realities of the Darfurians that count and until we ensure their stability and peace we still have a long way to go.

I appreciate all the comments you have left me and wish you all a sweet and peaceful new year. L’ shana tova.

–Sophie Glass

- 2 Comments

August 21, 2007 by admin

Genocide Olympics?

Mia Farrow is an active part of the “Dream for Darfur” campaign.

Officially, the Olympic Games are a series of sport competitions, but unofficially they are a global arena for political activities. In the 20th century, Hitler used the 1936 Olympics in Berlin as a platform to promote Nazism; the Palestinian extremists “Black September” killed Israeli athletes at the 1972 Olyimpics Games in Munich as a display of their anti-Zionist beliefs; Jimmy Carter pushed the United States to boycott the 1980 Moscow Games as a response to Soviet aggression in Afghanistan; and South Africa was banned from participating in the Olympic Games until they ceased their apartheid policies in 1992.

And now in the 21st century, the Save Darfur Coalition is using the 2008 Olympics in Beijing as an opportunity to highlight the Chinese government’s compliance with the Sudanese government’s genocidal campaign against the Darfurians. China is the largest supporter of Sudan, buying approximately 80% of Sudan’s oil. Sudan uses a considerable portion of its oil revenues to finance the genocide in its western region of Darfur. Save Darfur’s latest campaign “Dream for Darfur” aims to shame China into pressuring Sudan to stop its genocidal practices and immediately deploy United Nations-African Union hybrid peacekeeping force.

The “Dream for Darfur” relay began in Chad on August 9 and will continue over the course of four months. It will pass through cities that have historical ties to mass atrocities including: Yerevan, Sarajevo, Berlin and Phnom Penh, as well as many other cities in the United States.

The anti-genocide activists’ clamor over the “Genocide Olympics” has already influenced Steven Spielberg to demand that China change its policy towards Sudan or else he would step down from his position as the 2008 Olympics’ artistic director. Immediately following Spielberg’s threat, China sent a special envoy to Sudan.

When did celebrities replace politicians, and sport competitions replace international diplomacy? Why is Stephen Spielberg, and not President Bush, writing letters to China’s President Hu Jintao? It seems that our world leaders’ ineptitude at resolving the crisis in Darfur has left a vacuum that is being filled with athletes like Joey Cheek who donated his Olympic prize to Darfur relief efforts, and actors like Mia Farrow, who recently carried the Dream for Darfur Olympic torch in Kigali, Rwanda to commemorate the Rwandan genocide.

Regardless of whether it is right for sport competitions and celebrities to take the place of international diplomatic forums and politicians, the reality is that the 2008 games are politically charged. While the “Dream for Darfur” torch is traveling across the globe, the people of Darfur must continue to wait for the relief they have been falsely promised countless times by politicians who crudely allow athletes and celebrities to do their work for them.

–Sophie Glass

- 2 Comments

August 14, 2007 by admin

From Khartoum to Jerusalem

A Sudanese refugee child in Israel.

Photo: Ariel Jerozolimski

It is 1,128 miles from Khartoum, Sudan to Jerusalem, Israel. Many Sudanese travel at least this distance to reach Israel in order to escape persecution or to seek economic opportunities. Just this past weekend 70 Sudanese refugees joined the other 1,200 Sudanese refugees and illegal immigrants already living in Israel. These immigrants have found shelter in Kibbutzim and private homes but the daily influx of Sudanese has unfortunately led to the state-sanctioned policy of housing Sudanese men in Ketziot prison, alongside security prisoners. The lack of shelter options, health-care and education are just a few of the problems the refugees have faced since arriving in Israel. These issues have raised the question: does Israel have a unique responsibility to shelter and provide for refugees?

Interior Minister Meir Sheetrit announced that a top priority is to build a fence along the Egypt-Israel border to prevent the illegal flow of immigrants and refugees into Israel. As for the illegal immigrants that are already in Israel, Prime Minister Olmert’s bureau recently announced that Israel would absorb the roughly 300 refugees from Darfur, but will deport migrant workers and non-Darfur Sudanese people to Egypt. This decision is distressing because Egypt recently shot and bludgeoned several Sudanese asylum-seekers trying to cross the border into Israel and refugees confessed that they were persecuted while traveling in Egypt. These events indicate that deportation to Egypt could threaten the refugees’ safety.

Israeli university students have become particularly active on this issue and launched a petition against deporting Sudanese asylum-seekers to Egypt. 63 members of Israel’s 120-member parliament have signed the petition that declared: “The refugees have sought protection and sanctuary in Israel. The history of the Jewish people and universal moral values mean [that] we have to offer it.” Knesset Member Yuli Edelstein echoed many people’s concern when he said, “The State of Israel has to do all in its power to aid the Darfur refugees, because they’ve been through a terrible massacre, and returning them to where they’ve fled from could cost them their lives.” Another Knessest member and signatory Zevulun Orlev said that, “Jewish morals and Jewish history obligate us to treat refugees in peril with the utmost sensitivity.”

I believe that it is important for Israel to accept the Sudanese refugees and that any housing, educational and health-care issues can be overcome by true political will. These refugees would not have been displaced had the international community intervened before the conflict mounted to its current humanitarian crisis. Many countries, namely the United States, have spoken-out against genocide in Darfur, but have not committed military forces due to political and logistical reasons. Actively accepting some of the 2.5 million Darfurian refugees is a non-military display of commitment to the lives of Darfurians. While the world callously delays the implementation of a robust UN-AU peacekeeping force, the minimum that the international community could do is offer protection to the refugees.

–Sophie Glass

- 2 Comments

August 7, 2007 by admin

Interview with Leora Kahn

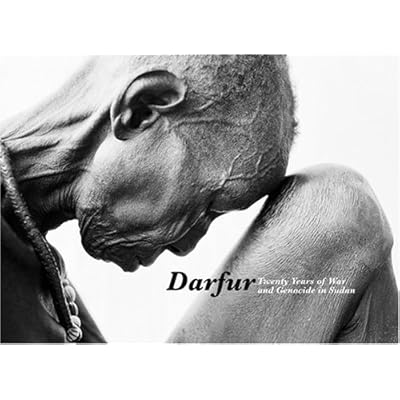

I had the opportunity to interview Leora Kahn, the editor of Darfur: Twenty Years of War and Genocide.” This recently published book covers the last two decades of conflict in Darfur through harrowing photographs and personal testimonies.

SG: What is the source of your interest in the genocide in Darfur?

LK: I have worked on genocide-related issues for many years, including editing “When They Came to Take my Father,” which chronicles the lives on Holocaust survivors. However, in 1994, I watched the genocide in Rwanda take place and didn’t do enough. When the genocide in Darfur came to my attention, I knew I shouldn’t stand by like I did then.

Most people think that the genocide in Darfur started in 2003; however, the title of your book states that war and genocide have been taking place in Darfur for 20 years. Can you explain that?

Genocide happens incrementally. In Darfur, the conflict had been building for many years before the genocide really began. A series of factors including, poor economies, corruption, authoritarian governments and environmental devastation can lead to genocide. There are many points along the way to genocide that other nations can intervene.

What inspired you to create this book?

I was sitting around with photojournalists and editors and we were discussing how we could make a difference within our field. We wanted to go beyond conventional assignments; we really wanted to go in and strategically use photography as a way to change people. We hope this book inspires people to do that.

Can you elaborate on the relationship between photography and social change?

Photography is a great tool to promote dialogue and dialogue promotes understanding, which is the first step of social change. These beliefs are the basis of the organization I started called Proof: Media for Social Justice. We primarily work with post-conflict societies such as Rwanda, but also inner cities in the United States. Proof’s projects will be more than just photography books. We are taking a more holistic approach to meet the needs of the communities we are documenting. For instance, we are including teaching packets with the books.

You clearly believe that photography has a great potential for change. Do you think the mainstream media’s visual coverage of Darfur is living up to the potential you spoke about?

No! It’s not strong enough. Every day, there should be photographs of Darfurians in the newspapers. Photographs taken during WW2 and Vietnam truly changed the world. If you have just one iconic photo, it really can make a difference.

DARFUR: 20 YEARS OF WAR AND GENOCIDE

Edited by Leora Kahn

Photographs by Lynsey Addario, Pep Bonet, Colin Finlay, Ron Haviv,

Olivier Jobard, Kadir van Lohuizen, Chris Steele Perkins, and Sven Torfinn

Essays by Jonathan Alter, Larry Cox, Mia Farrow, Colin Finlay, Ryan

Gosling, Nicholas D. Kristof, Susan Myers, and John Prendergast

–Sophie Glass

- 3 Comments

July 31, 2007 by admin

Divestment as Tzedaka

The Torah mandates that every Jew give a portion of her harvest to the poor as a form of tzedaka (Leviticus 19:9-10). Whereas our ancestors reaped their annual harvest, many people today reap the dividends from their annual investments. If the Torah were written in 2007 when people learned how to invest in stocks, I would imagine that there might be whole chapters devoted to how to invest ethically in the stock market instead of chapters dedicated to how to leave the grapes on the ground for your hungry neighbors to gather.

Many people think of tzedaka as a positive act of giving money to an organization or a person in need. However, the word Tzedeka comes from the word tzedek, meaning justice. Therefore, the act of withdrawing your money from offending companies is certainly an act of tzedaka.

Although there are no specific commandments in the Torah decreeing, “thou shalt only invest in companies that have no ties to genocide,” many people have decided to divest from companies that are funding the genocide in Darfur through supporting the Government of Sudan. Genocide is an expensive venture and the Government of Sudan depends on foreign investments to carryout its heinous crimes. Foreign direct investment helps fuel Sudan’s oil industry and a shocking 70% of the oil revenues fund Sudanese military expenditures, including the genocide in Darfur. By removing funds from companies in Sudan, you are pinching the Government of Sudan’s purse and preventing them from carrying out their atrocities. This approach is promising because the Government of Sudan has historically been more responsive to economic pressure than it has been to political pressure.

But which companies should states, cities and individuals divest from? The Sudan Divestment has identified companies that meet the negative criteria of (a) having a business relationship with the Government of Sudan (b) not significantly benefiting underprivileged Sudanese people and (c) not establishing a corporate governance policy regarding the genocide in Darfur. By identifying companies on the basis of these three criteria, the Sudan Divestment Task Force hopes to avoid the unintended consequences of divestment, including unemployment for the innocent civilian population.

Divestment as a form of tzedeka has found many supporters. For example, 20 states, 9 cities, 54 universities, and countless individuals have divested from companies that are indirectly supporting genocide.

If you want to get involved with this powerful movement, you can join your state and city’s divestment campaigns (or thank your Governor for divesting if he or she already has). If you are a student, you can join or start your school’s divestment campaign. If you are an investor, you can make your own investments free from the offending companies of the Task Force’s targeted list by screening your investment portfolio.

The 21st century has complexities that the Torah could not have anticipated. However, the underlying teaching of the Torah is “justice, justice, justice shall you pursue.” Divesting from offending companies in Sudan is one way you can pursue justice by helping to end this atrocious genocide.

–Sophie Glass

- 3 Comments

July 24, 2007 by admin

Midwifery as Activism

Fleeing the Janjawid isn’t the only way that Darfurian women are fighting for their lives—they are also struggling to prevent maternal mortality by becoming midwives. Sudan has the fifth-highest maternal mortality rate in the world, with 17 out of every 1,000 women dying while giving birth. This startling figure is partially caused by a lack of trained local midwives to compensate for the country’s severe doctor shortage and limited number of hospitals. With the help of humanitarian aid organizations, the Midwifery School of El Fasher in Darfur is training students to help women in their community give birth . This year, 82 midwives graduated with the expertise to handle births within their refugee communities.

Midwives are not only important to prevent deaths during labor, but also to reduce post-natal complications and their societal ramifications. Traditionally, Darfurian women marry at extremely young ages and conceive children as soon as their bodies allow them to. Having children in your early teens can lead to post-natal complications such as fistula (a disease that destroys connections between organs, leading often to debilitating and ostracizing incontinence). Women who were raped by the janjiwid militia and Sudanese Army also experience reproductive difficulties and painful post-natal conditions. Sadly, women suffering from these conditions are often ostracized by their husbands and their communities. Midwives can help avoid these unfortunate circumstances by providing proper natal care and emotional support. The Dean at the Midwifery School of El Fasher said that enrollment rates are rising and their wait list grows longer every year.

As a Jewish-American woman, I could learn a lot from the Darfurian women’s growing interest in midwifery and their commitment to reproductive health. Many women here in America do not have access to adequate natal and post-natal treatment due to the rising costs of health-care. This doesn’t necessarily imply that I should become a midwife (although Hebrew women are the oldest recorded midwives), but it does mean I should join the advocates in my community who are working towards reproductive health for women. From Sudan to the United States, it is inspiring to see how women are working to ensure the reproductive health of their sisters and friends.

–Sophie Glass

- No Comments

July 17, 2007 by admin

Not on Our Credit Cards

These days it seems to me like I could end the genocide in Darfur with a little Internet shopping. For example, I could start by purchasing a Green Day T-shirt that promises to end the violence in Darfur; or I could buy “colonial style leatherware” designed by George Clooney, Brad Pitt and Don Cheadle under the clothing label “Not on Our Watch.” But since clothing isn’t my thing, I could always buy “Instant Karma,” a CD recently released by Amnesty International as part of their Darfur campaign. The title of the CD (taken from a John Lennon song) illustrates the impatient attitude that characterizes 21st century consumer and cyber activism. The stylish Instant Karma website entreats me to sign a petition, of which only a line of its text is displayed (I had to click a link to actually read the petition).

Is this combination of consumerism, technology and compassion a brilliant fusion destined to save the world? Or, is it a shallow way of feeling like you’re doing your part to help the world, while getting a really sweet T-Shirt in the process?

By turning to Jewish texts, we can find some answers. Judaism continuously stresses that charity is not sufficient to Tikkun Olam, repair the world. Instead, Jews must be holy and engage in tzedekah, a Hebrew word derived from tzedek, meaning “justice.” Tzedekah is not limited to giving money to support charitable causes, such as buying a Darfur T-Shirt. According to the medieval Jewish scholar Moses Maimonides, one of the most important acts of tzedekah is helping a poor person get a job, instead of giving a poor person money. In other words, to pursue justice you must take out your work-boots and not only your credit card.

It is logistically difficult and incredibly dangerous to take out your work-boots by personally visiting Darfur, however, there are other ways to get actively involved with ending genocide. I recently spoke with Dan Feldman, a former Assemblyman of New York who informed me that in his opinion, the most powerful way to enact change is to personally visit your elected officials. He basically said that online petitions barely influence decisions because they are so easy to sign that they don’t indicate any true commitment to the cause.

I believe that consumer activism is a shallow solution to deeper problems that require our full attention. While it is important to monetarily support the issues we care about, we mustn’t feel complacent after purchasing a leather jacket, even if it dons the label “Not on Our Watch.”

Just yesterday, the U.S. reported that the Sudanese government has resumed bombing civilian targets in Darfur. This sort of widespread government-sponsored terror is not going to end with buying a T-Shirt from the comfort of our computers. Unfortunately, ending genocide is not as “instant” as our credit-card transactions.

—Sophie Glass

- 4 Comments

July 10, 2007 by admin

The Four Questions About Genocide in Darfur

Asking questions is a core tenet of Judaism. “The Four Questions” during Passover is just one example of how Jews question and analyze our traditions and the world. The genocide in Darfur is not a straightforward situation and the news often glosses over explanatory details, leaving concerned individuals confused and overwhelmed. Let’s try to clarify this complex crisis in Darfur by answering four of the most common questions I hear regarding the genocide taking place in Darfur.

Is it really a genocide?

In 2004, the United States officially declared that the “conflict” in Darfur was a genocide because the situation met the criteria outlined by the Geneva Convention in 1951. Former Secretary of State Colin Powell said, “Killings, rapes, burning of villages committed by Janjaweed [militias] and government forces against non-Arab villagers… [were] a coordinated effort, not just random violence.” He then said, “genocide has occurred and may still be occurring in Darfur.” Unfortunately, the United States has not followed up its bold proclamation with bold action.

Despite the abounding evidence and the US declaration of genocide, The United Nations has concluded that genocide is not taking place in Darfur. The UN admitted that the Janjaweed were carrying out “war crimes” against the civilians of Darfur, and some individuals might have “genocidal intent;” nevertheless, the UN has ruled that the central government of Sudan is not guilty of intentionally carrying out genocide. If the UN officially proclaims that genocide is occurring, they are legally bound by the Geneva Convention to intervene. This mandated intervention, along with economic interests in Sudan, are some of the factors deterring the UN from calling the situation by what I believe to be its rightful name: genocide.

How Many People Have Died?

The real answer is that nobody knows. The New York Times lists the number of civilian deaths at 200,000 and the Washington Post estimates 180,000, while the Save Darfur Coalition calculates total deaths at 400,000. Because of the severe lack of security, there are practically no fact-finding missions or humanitarian aid groups able to survey the population. With scarce investigative teams and a limited NGO presence, countless Darfurians are dying without a trace.

Who are the rebels?

The rebels refer to the groups in Darfur that are fighting the Government of Sudan. Two of these groups, The Sudan Liberation Movement/Army (SLM/A) and the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) led an uprising in 2003 against the Government of Sudan (this uprising led to the Government’s genocidal retaliation). The rebels’ objectives range from completely seceding Darfur from Sudan, to gaining increased political representation and power within the central government. Excluding a brief unity in 2006, the rebel groups are divided into countless factions and are unable to form a strong front to stand up to the Government of Sudan.

What can I do to help?

Use your own strengths to be an advocate for the people of Darfur. For example, you can create photo exhibits to educate others, write personalized letters and make phone calls to your members of Congress, create a short video for Darfur or organize a fundraiser. For more specific ideas, visit the genocide intervention website.

–Sophie Glass

- 5 Comments

July 2, 2007 by admin

Responding to Rape in Darfur

To state it crudely, rape is the “trademark” of the current genocide in Darfur, the western region of Sudan. Genocide historians have remarked that although sexual violence has been a brutal component of past genocides, the scope and magnitude of rape in Darfur is unparalleled. Pamela Shifman, a U.N. expert on sexual exploitation, commented that rape is being used to “terrorize individual women and girls…to terrorize their families and to terrorize entire communities. No woman or girl is safe.”

The majority of the sexual assaulters are part of the Janjawid militia, a tribe that the Sudanese government has enlisted to carry out the genocide. A Darfurian refugee from Mukjar confessed, “When we tried to escape they shot more children. They raped women; I saw many cases of Janjawid raping women and girls. They are happy when they rape. They sing when they rape and they tell that we are just slaves and that they can do with us how they wish.” In addition to frequently contracting HIV/AIDS and experiencing reproductive complications, women also endure societal ostracism after being raped.

It is clear that we must take action against sexual violence in Darfur. However, what sort of action will truly be effective and not just guilt-alleviation for those of us who are aware of the situation?

I believe that the most powerful solutions are the innovative ones that look beyond the problem itself and find solutions in unexpected ways. Solar Cookers Internationals is an organization that has creatively responded to this crisis by working with Jewish World Watch and the KoZon Foundation (a Dutch charity) to disseminate solar cookers to the Darfurian refugees living in Iridimi and Touloum refugee camps in Chad. With solar cookers, women and girls no longer need to leave the refugee camp to go out foraging for wood. The task of collecting firewood is physically exhausting, environmentally damaging, time-consuming and extremely dangerous. When women leave their refugee camp they face a high risk of being gang raped by the Janjawid and men risk murder. However, after completing a training workshop, Darfurian women and girls can acquire their own solar cookers to safely sterilize water and cook food without stepping foot outside the refugee camp, where the Janjawid and Sudanese soldiers roam and plan their next attack.

To ensure security for the 2.5 million Darfurian refugees, they ultimately need a robust international peacekeeping force. According to a recent agreement, the United Nations is planning on working with the African Union to provide a “hybrid” security force in Darfur. However, it is unclear when the United Nations troops will actually be deployed and the African Union is too under-funded and understaffed to deal with the crisis alone.

In the murky waters of failed international interventions, we must rely on the compassion, creativity and goodwill of individual groups. Thankfully, organizations such as Solar Cookers International have confronted the issue of sexual violence through their innovative solar cooker initiative, which has ensured that at least the women of Iridimi and Touloum refugee camps do not have to risk being raped merely to cook dinner.

–Sophie Glass

- No Comments

June 25, 2007 by admin

Training Our Instincts Toward More Distant Compassion

Ideally, we would have infinite hours in a day to tikkun olam, help repair the world. In reality, the amount of time we set aside for this mitzvah is limited. This begs the question: where should we direct our good intentions with the finite time and energy we have? Should we focus on our local community and the people we understand? Some argue that the more personal your connection to a person, the deeper your empathy and the greater your motivation to assist him or her. Another opinion is that we should direct our attention to the most clamant situations, irrespective of their geographic or relational distance.

For the past three years, since before I began college, I have been actively involved in STAND, a student movement that works to end the ongoing genocide in Darfur, Sudan. I have attended conferences and spearheaded my school’s chapter of STAND. At first glance, my efforts are directed towards the most dire situations (genocide), as opposed to the most immediate, local causes (hunger and homelessness in NY, immigration issues etc).

But if you take a second look, my Darfur related activism includes personal connections. To see the people of Darfur as the faraway “others” with no connection to my life would be denying several important bonds that we share. For instance, my family history includes my grandparents’ escape from the Holocaust. This painful and personal legacy of genocide ties me to Darfurians, who are currently enduring genocide. I imagine that the grandchildren of those who survive the genocide in Darfur will recall their ancestor’s stories, just as I, a third-generation survivor of the Holocaust, can recount my grandparents’ memories of surviving.

Additionally, my female identity ties me to the women of Darfur. The women of Darfur endure, and often die as a result of, sexual assault inflicted by the janjaweed militia and the Sudanese army. I have never experienced anything similar to the gruesome and horrific sexual abuse that these women have (baruch hashem). However, even in the United States I know that I am at risk for sexual assault and abuse. I never walk home alone in the dark and have learned how to spot and avoid sexually aggressive men. Living in this world as a woman is not entirely safe yet, and my fight to protect my body is intimately related to my fight to protect the women of Darfur.

These examples illustrate how even though I have never met a person from Darfur, nor have I had the opportunity to travel to Sudan I still feel that there are tangible links between my life and the life of a Darfurian. I believe the real challenge is not to choose whether to be a community activist addressing local issues or a “neediest cases” activist, often acting on behalf of people you have never met. The more important struggle is to turn these seemingly distant and harrowing crises into personal issues. The power of the media and our access to information allows us to see our own reflections in the faces of others, though they live thousands of miles away and speak foreign languages. With our limited energy, I believe that we must address the neediest cases with the compassion and attention to complexity that we instinctively grant to our neighbors.

–Sophie Glass

- 2 Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...