Tag : Roe v. wade

March 5, 2020 by Chanel Dubofsky

What Happened at the Supreme Court Yesterday?

“Looming” is an appropriate word to describe the atmosphere around the current abortion rights case before the Supreme Court. On March 4th, oral arguments were heard in June Medical Services V. Russo, while outside the court, pro-choice activists, along with anti-abortion protesters, rallied.

While a decision won’t come from the court until this summer, here’s what you should know right now about the case and its implications for abortion access.

What is June Medical v. Russo?

This case is a challenge to a Louisiana law (Louisian Act 620, or Louisiana Unsafe Abortion Protection Act), enacted in June 2014, which requires abortion providers to have admitting privileges to a hospital within 30 miles of where the abortion is performed. June Medical is identical to Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, struck down in Texas in 2016, declaring that requiring admitting privileges placed an “undue burden” on those seeking abortion care. In September 2018, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals revisited the 2016 decision and declared that, unlike in Texas, Louisiana actually needs the admitting privileges law to be in place in order to ensure the health and well-being of pregnant people. The question before the Supreme Court is whether or not Louisiana can enact Act 620, or if the law violates the right to abortion access.

- No Comments

January 21, 2020 by admin

Roe Still Stands — But Not for Everyone

June 27, 2018 began like an ordinary workday. A recent college graduate, I was spending the summer interning at NARAL Pro-Choice Texas, doing grant research.

I was sitting around a table with the staff pitching my initial findings when our phones buzzed. A breaking news alert: Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy had announced his retirement.

The calls from concerned Texans started pouring in immediately. Kennedy was a decisive swing vote on abortion and other issues of reproductive health. What would his retirement mean for the future of reproductive rights?

- No Comments

November 5, 2019 by admin

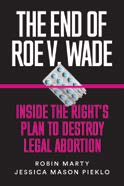

The Right’s Plan to Destroy Legal Abortion

Forty-six years after the US Supreme Court ruled that state bans on first trimester abortion violated the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of privacy, a well-organized and well-funded anti-choice movement remains hellbent on ending access to both surgical and medical (mifepristone followed by misoprostol) procedures.

Forty-six years after the US Supreme Court ruled that state bans on first trimester abortion violated the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of privacy, a well-organized and well-funded anti-choice movement remains hellbent on ending access to both surgical and medical (mifepristone followed by misoprostol) procedures.

This isn’t new.

- No Comments

November 4, 2019 by admin

Molly Wernick Advocates for the Separation of Church and State

When Justice Anthony Kennedy announced his retirement from the U.S. Supreme Court in June 2018, fear, panic, and dread rose up in the throats of pro-choice Americans. The precarious position of Roe v. Wade, the 1973 decision protecting a person’s choice to have an abortion, was one that people had been well aware of since before the election of Donald Trump in November 2016, but Kennedy’s retirement provided the opportunity to appoint another anti-choice justice who could eviscerate Roe if and when the time came.

For Molly Wernick, who oversees Community Engagement initiatives for Habonim Dror Camp Galil in Southeastern Pennsylvania, the appointment of Brett Kavanaugh, Trump’s choice to replace Kennedy, meant the transformation of the abortion debate, from “something that didn’t threaten my life and future to something that did.” Her response came in the form of an article for Medium, written the second day of Rosh Hashanah 2018, in which she wrote about learning that she and her husband were both carriers of Tay Sachs disease, an inherited, degenerative condition which leads to death in children, typically by about the age of four. In a post-Roe America, Wernick reflects, she, as a person of privilege, would be able to access an abortion, which isn’t the case for many others. As a result of the article, Wernick told Lilith, people came forward to tell their stories of abortion and miscarriage, stories they had kept secret until then, out of a sense of shame.

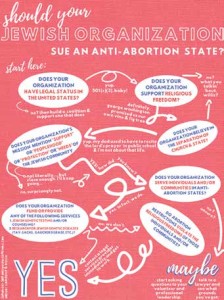

But there’s another element to the abortion rights conversation, and that has to do with the separation of church and state. “It’s also a slap in the face to my own religious freedom,” says Wernick. While the Christian belief that life begins at conception controls the anti-choice actions leading to abortion legislation, Wernick points out that that’s not what the Jewish view of abortion is. “For the first 40 days of gestation, a fetus is considered “mere fluid” (Talmud Yevamot 69b), and the fetus is regarded as part of the mother for the duration of the pregnancy,” wrote Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg, on Twitter in May 2019. (Read the entire thread, it’s a great 101 on Judaism and abortion.) Restricting, and attempting to ban legal abortion altogether on the basis of Christian interpretation, explicitly violates the U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment, which protects freedom of religion.

From the Lilith Blog.

- No Comments

July 16, 2019 by Jamie Zabinsky

“Failed Self-Abortion With a Wire Hanger”: A Letter from a Namesake to an Ancestor

Dear Jennie,

Despite our shared name, your life and death were clarified for me only in college, when I started to develop a vocabulary for seeing the world through gender, power, class, suffering and solidarity. I began to realize that the way my family had passively glorified your story as one of dire poverty alone missed several crucial, intersecting points—your gender, the drive to control the female body, autonomy, motherhood, the value of a life, and the devastation of death and desperation. No one mentioned until recently, at least to my knowledge, that you likely struggled with depression. Me, too.

- 3 Comments

July 2, 2019 by admin

Susan Weidman Schneider on the Jewish Stake in Abortion Rights

In 1970, three years before Roe v. Wade gave women a constitutional right to abortion, letters addressed to medical personnel across the U.S. announced that in New York State abortions had become legal up to the 24th week of pregnancy. Doctors elsewhere could refer women seeking abortions to facilities in New York. Safe, legal abortions were at last available—for some women.

The experience could still be fraught, however. One New York City obstetrician-gynecologist told me of women coming to his office bearing a deliberately nasty letter of referral from their local doctor. “To the Abortionist” was one such salutation, with the envelope deliberately left unsealed, so that the woman could have the unsettling experience of reading, en route to her appointment, that she was about to murder her baby.

What underlies such a letter is same punishing, patriarchal, judgmental attitude that drives today’s challenges to Roe. It’s what commentator Rachel Maddow describes as the Trump administration’s “performative cruelty,” and includes decidedly anti-“life,” anti-child policies like the separation of infants and children from their parents at the southern border of the U.S. The laws Georgia and Alabama passed this spring don’t just fly in the face of federal law. “Instead,” The Washington Post reminded us, “they represent a dramatic and unprecedented escalation of antiabortion law in the United States… far, far worse than a simple Roe reversal.”

These new laws are greasing a once-unimaginable retrograde slide. The actual wording of Roe states that “unduly restrictive state regulation of abortion is unconstitutional.” Yet the new laws want to refuse exceptions even in cases of rape or incest.

By forbidding almost all abortions, these laws, in addition to their vicious misogyny, are a violation of our rights as Jews to practice our religion. Here’s a brief refresher course: Jewish law privileges the life of the mother over the status of the fetus. When a woman’s life or health are endangered by pregnancy, the fetus becomes a “pursuer,” as if the woman were under attack by an enemy. Simply put, if the woman’s health—including in some instances even her mental health—is threatened by the continuation of the pregnancy, Jewish law declares the pregnancy may be terminated.

Jewish women took this understanding to heart when, in 1987, conservative judge Robert Bork was nominated—and failed to be confirmed—to the Supreme Court. Widespread opposition hinged in large part on Bork’s anti-abortion stance. When leaders of Jewish women’s organizations gathered to strategize, they focused on how it stifled freedom of religion. Yet last year when Brett Kavanaugh was nominated (and later confirmed) for a seat on the Court, freedom of religion had faded as a valid opposition point.

In our precipitous present, what can we learn from these earlier struggles?

Whisper networks used to signal to pregnant women where they could obtain a sometimes safe, sometimes life-threatening abortion. And then came Jane, the courageous cadre of young women, most not medical professionals, who learned how to perform abortions themselves. “Jane” performed an estimated 11,000 abortions in the years just before Roe.

There was no technology then to monitor women’s bodies via ultrasound, “proving” the gestational age of the fetus or that it already had a heartbeat. In those days a miscarriage was a miscarriage, perhaps a sad event; now, a woman who miscarries risks being accused of homicide.

So pay attention to local rulings, like requiring a woman seeking an abortion to undergo an unnecessary vaginal probe,or be forced to view an ultrasound of the fetus. “Mandatory ultrasound laws have no medical justification,” according to NARAL, “and are designed by anti-choice politicians solely to intimidate, shame and harass women who seek abortion.” Right!

Better news: DIY medical abortions are now possible even in the second trimester of pregnancy (13–24 weeks) using Mifepristonemisoprostol. A New York Times op-ed even advises women to get prescriptions for these drugs filled now, so you can stockpile the meds in case Roe is revoked. And abortion costs are now abated some by women and men donating to abortion funds. New York City this spring allocated $250,000 to help women in need pay for abortions—the first municipality to do so. (This with advocacy support from, among others, NCJW-NY.)

Remember from the AIDS epidemic that Silence = Death. If Roe is overturned, we’re talking women’s deaths. So ally yourself publicly right now with organizations supporting reproductive rights. Advocate; tell legislators where you stand. Get ready to speak out and change minds. And prepare to be shocked, as a friend of mine was when one of her book-group buddies declared categorical opposition to abortion.

Ask rabbis to give sermons on abortion rights, Jewish law and the threat the new legislation poses to religious freedom. Encourage clergy to earmark discretionary funds for low-income women needing an abortion. Let educators know you expect them to position abortion rights as an important tenet of Jewish law. Lobby religious and secular schools to provide accurate and useful sex ed, so that all students understand how to prevent pregnancy.

Fight parental consent or notification laws; 39 states have them, and they undermine patient autonomy, according to the American Medical Association ethics journal. The journal reinforces something else you know. Any law “supporting physician refusal to refer patients for abortion on conscience grounds obscures the fact that providing abortion is, for many, also a conscience- and values-based decision.”

In struggle,

Susan Weidman Schneider

Editor in Chief

- No Comments

January 10, 2019 by admin

In Med School Before Roe v. Wade

We chatted as the dialysis shift began. She was a young nursing student whose name and face I still remember five decades later, but I will just call her “Jane Roe.” She was from the Virgin Islands and had come to New York for nursing school. She was nearly done—justifiably proud, since she had funded it herself. I was a fourth-year medical student doing an elective rotation on what was called the “Renal-Metabolic Ward.” The dialysis machine was working well, so we continued to talk when we could as the hours went by. It was 1968, and dialysis would not be funded in the United States for another half-decade, which meant that any patient undergoing long-term dialysis had to have the means to pay for the treatments, one way or another, or the consequence was obvious—death, since kidney transplantation was in its infancy.

Dialysis shifts were long, and we changed the dialysate fluid (then called the “bath”) halfway through the treatment. We exchanged stories, as students do, about how school was going, what we’d seen on the floors, and what plans we had. Jane said she hoped to go back to St. Croix to serve people in her rural community. She liked it there better than the cold Northeast United States, anyway, she said.

Toward the end of the shift, some alarms on the machine went off, and we all did our part to stabilize the blood flow and the dialysate flow. Nothing so exact as modern hemodialysis, which delivers nearly automatic and precise dialysis care in comparison. But that treatment ended well.

There is another part to this story: Jane, the nursing student, was, in fact, the dialysis patient, and her odyssey had included far more than nursing school. Four months before I met her, Jane realized she was three months pregnant, despite always using contraceptives. She had a fiancé but was not yet married, and neither of them had the means to provide for a baby, so they reluctantly decided that terminating the pregnancy was the only choice. They planned to have children later, when they were both ready and could truly provide what they felt was right for a child. That way, Jane would also be able to continue her training and become a nurse.

So Jane did what thousands of young women were forced to do in the 1960s—she underwent a back-alley abortion. Though she had worried about going through with it, other young women she knew had used the same abortion doctor and had been fine. She went for the procedure with fear but also determination. Unfortunately, afterward Jane was not fine at all: she developed sepsis and multiorgan failure. She survived after weeks of hospitalization and near-death episodes, along the way enduring a hysterectomy and severe acute kidney failure, with bilateral cortical necrosis. Acute dialysis saved her life. However, Jane’s kidney function thereafter was essentially nil, and she continued on thrice-weekly dialysis, donated as compassionate care by the hospital. Jane and her fiancé married while she was in the hospital, hoping that she would gradually improve, receive a transplant, and resume her studies. She told me she was sad that she would never have a biologic child, but she was full of plans for the future.

A few weeks later, another complication developed—acute bleeding, with a hemothorax. I was the medical student on that dialysis shift, too. Jane was too ill to speak, though she was conscious and nodded hello, offering a weak smile. I chatted with her at the start of the dialysis run, but her status deteriorated, rapidly. There was a code. Though the team tried everything they could to resuscitate and stabilize her, she did not make it. We all cried.

Five years later, Jane would not have died—abortion had become legal in the United States. Over the ensuing decades, safe and legal abortion became standard. Thus, Jane would have, like me, become a grandmother, and would probably still be working and serving others.

Why am I telling Jane’s story now? The lack of legal and safe abortion before the Roe v. Wade decision of 1973 killed and maimed thousands of young women. Should that decision be overturned and abortion again become illegal, there will be countless more young women like Jane.

From New England Journal of Medicine, August 23, 2018. Used with permission.

- No Comments

January 10, 2019 by admin

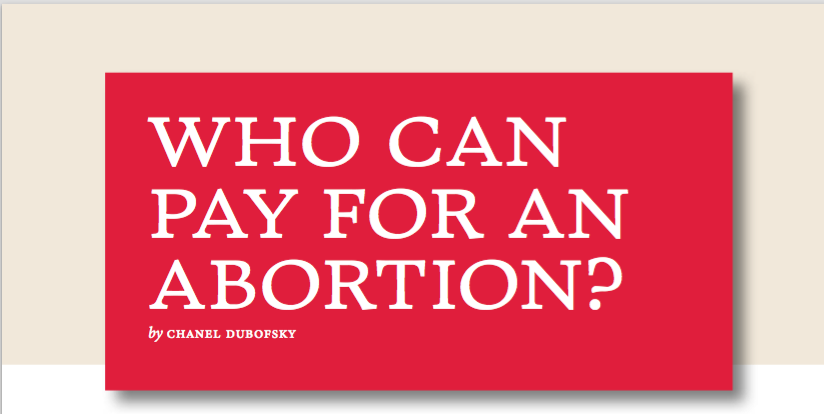

Who Can Pay for an Abortion?

Money has always made it easier for some women to obtain a relatively safe (if illegal) abortion. Talk to women who came of age in the 1950s or 60s, decades before abortion became legal in the U.S., and you’ll hear tales of someone’s flight to Puerto Rico to have an abortion. Or suspicions that a respected doctor who was a family friend might have performed an abortion in a safe surgical operating room in the guise of an “appendectomy.” Whether the details are entirely accurate in these recollections, the theme rings true: women with access to money had a much better chance of also being able to access abortions. It’s shocking to realize that economic privilege is once again the reality of abortion access in the era of today’s Supreme Court. Today in the United States, if you are a person of means seeking an abortion, you can still get one. Everyone else? Good luck.

Money has always made it easier for some women to obtain a relatively safe (if illegal) abortion. Talk to women who came of age in the 1950s or 60s, decades before abortion became legal in the U.S., and you’ll hear tales of someone’s flight to Puerto Rico to have an abortion. Or suspicions that a respected doctor who was a family friend might have performed an abortion in a safe surgical operating room in the guise of an “appendectomy.” Whether the details are entirely accurate in these recollections, the theme rings true: women with access to money had a much better chance of also being able to access abortions. It’s shocking to realize that economic privilege is once again the reality of abortion access in the era of today’s Supreme Court. Today in the United States, if you are a person of means seeking an abortion, you can still get one. Everyone else? Good luck.

You may be wondering how this could possibly be true. How will money be able to circumvent laws and regulations that already severely limit reproductive rights in many states, and which point to an even more Draconian future? After all, Alabama and West Virginia recently passed anti-choice amendments, North Dakota and Mississippi each have only one abortion clinic, and even New York State’s abortion laws aren’t actually that great if you look closely. In addition, the appointment of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court has pro-choice folks rightly alarmed—Roe v. Wade, the1973 Supreme Court ruling that made abortion legal in the U.S. is already at risk of being overturned. Four states (Mississippi, Louisiana, North Dakota and South Dakota) have “trigger laws” in place which will automatically outlaw abortion if Roe is reversed; many other states have similar laws that will push the procedure to the very edge of legal possibility. And just because a state doesn’t have a trigger law on the books, that doesn’t mean it’s a safe haven—only a few states, like Massachusetts and New Mexico, have specifically declared they will protect abortion rights.

For many women, today’s reality already offers a window into life post-Roe. If you have money, it might not matter if there’s only one clinic in your state, or if laws in your jurisdiction ban abortions after, say, 15 weeks. Money will enable you to drive to that one last available clinic, take the day (or more than a day) of from work to have the procedure done, rent a hotel room if you need to stay overnight, provide childcare for the kids you statistically already have, or even leave the state—or country—to get an abortion if you need to.

Without the means to access these necessary aspects of obtaining an abortion, it doesn’t matter if abortion is technically legal, because it’s so out of reach.

Cue the 70 abortion funds that have sprung up over the last 25 years. Providing the bridge between having to carry an undesired pregnancy to term and being able to terminate the pregnancy, abortion funds are nonprofit organizations that offer financial and logistical help to women seeking an abortion. Some funding groups exclusively provide assistance in paying for the abortion itself, others cover the practical aspects of obtaining one (travel, childcare, translation services, etc.) in their purview, and some include funding for both. For women who rely on support from such abortion funds in order to get abortion care, what happens if Roe is legislated out of existence? What happens to abortion funds’ funding in places where abortion becomes illegal?

The answer: they become even more indispensable. “If abortion does become illegal in Alabama, we’ll simply set up relationships with clinics out of state and assist callers with funding for their procedures and travel, childcare, etc.,” says Amanda Reyes of the Yellowhammer Fund. “We already provide practical support in this way to several of our callers, so it will just become part of the regular process for assistance. I also imagine that funds in different states will probably coordinate state-level and regional volunteer support networks where folks can assist with rides and shelter if there isn’t funding for hotels and more.”

In fact, the rest of us may turn to the people who run abortion funds to learn how to navigate a world where abortion rights are on the edge of not existing. “Long term, abortion funds aren’t going anywhere,” confirms Laurie Bertram Roberts, executive director of the Mississippi Reproductive Freedom Fund. “We are the experts in helping remove barriers for people accessing abortion, and that work includes culture shift as well as protecting and supporting those who self-manage their abortions.”

In Kentucky, only one abortion clinic remains, the EMW Women’s Center in Louisville. EMW Lexington location was shut down in January 2017. Marcie Krim is the executive director of the Kentucky Health Justice Network; in addition to its Trans Health Program, its abortion fund offers financial support for transportation, lodging, childcare, and other expenses. The fund’s 50 volunteers already drive people out of state, often to Illinois (four hours, round-trip), and also get women to Colorado and Maryland, where abortion care is available later in pregnancy than it is in the rest of the country.

If Roe goes, Krim says, “expenses will rise significantly.” But, she clarifies, they’ve already gone up, not just because of the closure of the Lexington clinic, but also because of abortion restrictions, like a 24-hour waiting period and the parental consent requirement for those under 18. Both these restrictions can mean the difference between ending a pregnancy in the first trimester and the second, when the procedure becomes more expensive. “The more laws,” Krim says, “the longer people have to wait for their abortion.”

She relays the story of a teenage girl she was driving to the airport for an abortion. “She told me, “Before I found you, I was going to try to do this myself.”

“We know that Roe has never been a promise for abortion access,” says Yamani Hernandez, executive director of the National Network of Abortion Funds (NNAF). While the idea of Roe being revoked is definitely disturbing, “those realities are what we’ve been navigating for decades.” The average abortion fund, she says, has an annual budget of $76,000, and only 29 out of the 70 abortion funds in the U.S. have a paid staff member, meaning they are primarily volunteer- run. “Currently, it’s middle-income white people who volunteer, and we want… to make sure that the people answering the phones reflect the identities of the people who are calling.” Hernandez adds that in 2017, out of the 150,000 calls being made to abortion funds, only 30,000 requests were funded. “Abortion funds need five times the amount of money they have,” she says. “This is an unprecedented time, and we need unprecedented resources.”

Where in this opportunity for action can we find the Jewish community? What support might be forthcoming from Jewish sources, particularly in light of the fact that Jewish law mandates saving the mother’s life over saving the fetus? My search for rabbis with discretionary funds who would be eager to donate some of that money to abortion funds, or to people in their own communities in need of abortion, came up empty. (I’m not ready to say they don’t exist, just that I couldn’t find them.) That’s because while abortion rights may be a talking point in Jewish circles, the financial aspect has yet to fully penetrate, activists say.

“I don’t hear mainstream, social-justice-oriented Jews talking about abortion access,” says Leah Greenblum, the Chicago community director of AVODAH: The Jewish Service Corps. She also funds abortion via her work with the Midwest Access Coalition (mac), a practical abortion fund, which provides assistance with an abortion’s ancillary costs. “It would be a nice thing if rabbis made themselves knowledgeable about what resources exist—do research, keep up with laws, barriers, listen to organizations like Planned Parenthood, naral, Guttmacher—and took their cues from them,” says Greenblum. “We can’t just be passive, we have to talk about abortion and how it’s interwoven with race, class, gender, geography, health- care.” Greenblum says that her AVODAH coworkers have been supportive of her work with mac, and after an October 2018 article Haaretz included her in a profile of American Jewish women working to expand abortion access, a rabbi in Chicago became a regular mac donor. “If, as Jews, we’re interested in true liberation, abortion has a place in that,” she says.

The action—or inaction—of Jewish men can tell us a lot about how seriously they take the concerns of Jewish women, like access to abortion, and ultimately, bodily autonomy, says Rabbi Ruti Regan.

Regan notes that during the Kavanaugh hearings she saw many Jewish women attending protests, but not a lot of Jewish men, or major Jewish organizations. “If we took Jewish women seriously as Jews,” she says, “we would see things like Kavanaugh’s appointment and assaults on reproductive justice as a threat to the community and not ‘just’ to women.” She adds that during those fraught days, she heard condescending lectures from Jewish men urging Jewish women not to “freak out” and to remain civil, “as if nothing catastrophic was happening, and women were expected to just get over things.”

The truth is that Jewish tradition runs counter to that patronizing “deal with it” sentiment, says Regan, giving us a spiritual framework to mourn our past losses collectively. But in order to regroup going forward, “we need it clear that we value Jewish women’s lives.” Her question for Jewish men as we march into this uncertain future for reproductive autonomy goes beyond financial matters. She asks if men are ready to recognize the deeper social value of standing up for women’s lives: “Do you still think women are human beings when defending them would cost you something?”

Chanel Dubofsky writes fiction and non-fiction in Brooklyn, NY.

- No Comments

September 26, 2018 by admin

Worried About Roe Now? Welcome to the Fight.

The bombshell news that Justice Anthony Kennedy—a reliable pro-abortion rights vote—is retiring from the Supreme Court means that Roe v. Wade is truly, seriously imperiled. We could wake up within a few years to find abortion fully illegal in over 20 states.

Ironically, in recent months, right up until the Kennedy-related outpouring of fear we’re seeing, abortion rights advocates had noticed a growing fatigue around the issue, while access to abortion was eroded almost daily.

There’s a difference between abortion being legal, which it technically is as of now in the U.S., and being able to get an abortion if you need one. Because of the scarcity of abortion providers, the power of abortion stigma restrictions in individual states, and the existence of the Hyde Amendment, which prohibits the use of federal funds to pay for abortion, actually getting abortion care is a challenge at best for folks in rural areas, poor folks, people of color, and other vulnerable populations. For these people, abortion access has never been a guarantee, and Roe v. Wade is nothing but a gesture.

So what can be done in the face of danger from the outside and fatigue within—especially now that Roe itself is likely to fall? M., an abortion clinic escort in California, told me her organization has been losing escorts rapidly, since postelection energy wore off in 2016. “Even the generally woke-ish people in my life genuinely have no idea how precarious our situation is right now. It’s tough, because there are so many things that people are understandably prioritizing— the rise of fascists, immigrant detention, etc., but at the same time, people don’t understand that all of these things are connected.” CHANEL DUBOFSKY, the Lilith Blog.

- No Comments

August 20, 2018 by JoAnn Abraham

#MeToo, The Supreme Court, and Immigration Cruelty: Connected by Misogyny

At this summer’s ESPY, Excellence in Sports Performance Yearly, awards, the 141 survivors of sexual abuse by Dr. Larry Nassar (one of them was Olympian Aly Raisman) received a standing ovation. These women athletes had suffered for decades in silence, shamed into believing that they were at fault, or that what the doctor was doing was all right. They weren’t, and it wasn’t.

As the future of Roe v. Wade seems to waver, I thought about how, in this day and age, these young women weren’t even sure they had the right to determine when and by whom they could be touched. Only in the months since #MeToo did that change.

- 1 Comment

Please wait...

Please wait...