Tag : pennsyvlania

January 9, 2017 by admin

Overlooked Women at the Homestead Hebrew Congregation

Women of the Ladies’ Aid Society, Sukkot 1916. Courtesy of Caren Lever.

Since I’m the moderator, I’ll take the liberty of asking the first question,” said Betty Arenth, senior vice president of the Heinz History Center, at the conclusion of my lecture about the Jews in the former steel center of Homestead, Pennsylvania. I was eager to hear how she regarded the research I had undertaken at her archive.

“Where are all the women?” she asked.

Her question startled me. Indeed, my talk had touched upon only a few women from the community. But how had I, a lifelong feminist, never noticed their absence from the story I had been re- assembling since childhood?

My interest in Homestead’s Jewish community began with my father’s memories of his grandfather, Bernhardt Hepps (1863–1949), who had established its synagogue and cemetery. I wanted his stories to be true, because my very American upbringing seemed to belie such authentic roots. Although proof was elusive, I remained fixated on my great-grandfather’s forgotten past, though my obsession seemed trivial compared to all of the other goals I set for myself.

I graduated from Harvard with a degree in Computer Science and embarked on a career as a web technologist in New York City, taking on increasing responsibilities at start-ups and even The New York Times. When I became Chief Technology Officer for a division of NBC at only 30 years of age, I felt I had arrived.

Work was all-consuming, but along the way I managed to research Bernhardt in fits and starts. Eventually, I made a life-changing discovery: the records of his synagogue, the Homestead Hebrew Congregation, had been in a public archive all along! Despite having only a couple hours to review their records during my first visit to Pittsburgh, in 2010, many of my oldest questions were easily answered by a seven-page history of the congregation written by its longtime secretary, Ignatz Grossman (1868–1948), for the congregation’s 50th anniversary in 1944. But seven pages were nothing compared to the remaining 16 boxes of material I didn’t have time to review.

Back in New York, I couldn’t shake the feeling that I wasn’t done with the synagogue records, and that the synagogue records weren’t done with me. But what did that mean, exactly? The only path I knew how to follow involved servers and software, not history or archives. For four years the memory of those hours in the archive beckoned. In the summer of 2014 I suspended my career in order to move to Pittsburgh to research the Homestead Hebrew Congregation full-time.

Only six months later, I was lecturing at the History Center about how the synagogue’s meeting minutes, financial ledgers, correspondence, and other ephemera traced the early history of the community. I began with the first Jewish resident, who arrived just before the steel mill opened in 1881, and ended with the dedication of its first synagogue building in March 1902. I was pleased to have reconstructed such a rich story, despite my lack of training. When Betty asked her question, it hit me all of a sudden that the records I had been poring over were written by men about men, because only men could be members of this Orthodox congregation. Bernhardt and everyone else who had served as the synagogue’s founders, officers, directors, and committee members were men. The financial ledgers tabulated the dues the men paid, seats they purchased, and tsedakah they donated. The meeting minutes detailed the decisions they made, the controversies they overcame, the elections they held, and the committees they organized. Women couldn’t even attend meetings or vote. I often wondered if I, a committed egalitarian Jew, would have liked this community to which I had devoted myself. As a researcher, however, I had no problem accepting the community on its own terms—except that I had clearly been too careful not to distort their priorities through the lens of my own.

Within the synagogue records I had reviewed at that point, women rarely made an appearance. But, I admitted in response to Betty’s question, there were kernels of stories I could have included. Grossman’s 1944 history framed my lecture, and he had named three women, only one of whom I had mentioned: my great-grandmother, who laid the cornerstone in 1901. I could have also mentioned a “Mrs. Samuel Markowitz” who, in March 1894, “prepared dinner at her own expense” to celebrate the inception of the congregation. I had already mentioned her husband, since it was his inability to assemble a minyan on his father’s yahrzeit that roused the men to action, but what had life as one of the first Jewish women in this rowdy mill town looked like to her? Expanding my research to censuses, local newspapers, and city directories, I was able to return her name and biography to her. She was Lena (1860–1935), a Hungarian immigrant who came to the U.S. as a teenager and was then a 34-year-old mother raising a five-year-old and expecting her second. She was hardly a woman of leisure who had the time or finances to prepare a party for dozens of people. Like most housewives of her class, she was expected to contribute to the family’s finances. She likely helped run the family’s grocery and looked after boarders. She is the only woman named in connection with the founding of the synagogue.

Shortly after Lena’s dinner, the congregation’s first president died. Grossman’s history connected this tragedy to the community’s next milestone, its cemetery, but my thoughts lingered on the unnamed widow. With effort I found Clara (1859– 1925), a woman about the same age as Lena, who had also immigrated some time earlier, in her case from Prussia. She was left alone with four boys and two girls. The eldest was nearly grown, but he was “so wild” that his father, just weeks before his death, had asked a police officer to lock him up! This son left town soon after the funeral, leaving his mother to raise five children under 11 herself.

An advertisement for Segelman’s jewelry store in the Homestead Daily News dated November 29, 1897, three and a half years after Clara was left to run the store on her own.

Clara not only kept her husband’s jewelry store afloat, but maintained its position as one of the better stores in town, quite a feat for a business requiring specialized training she had not received. Her second son joined her in the store when he came of age, and her three other children who grew to adulthood graduated high school, very rare at that time, and established professional careers. Alone, Clara somehow managed better for her children than many of her contemporaries with working husbands.

These were the women I told Betty and the audience about: Lena, a name in the synagogue’s official history, and Clara, only a shadow. The name of one more early contributor had emerged from the synagogue records, a Mrs. Weisburg, whom the synagogue’s president praised for helping to make the parochet (curtain for the Torah ark) though she wasn’t a Homesteader. Contemporaneous newspaper articles added the names of the wives who made the Torah mantle and of two grown daughters of members, Laura Gluck and Bella Haupt, who presented the amud (lectern) cover.

I concluded my answer by explaining that these women and these small acts were all I had unearthed, but after the lecture, I felt chastened. These women all had stories, some of which I knew quite well. And besides them, there were many more related to the men mentioned in the synagogue records, whose stories I hadn’t even begun to reassemble. While it is understandable that Grossman organized his 1944 history around the deeds of men, it was short-sighted for me of all people to continue following his lead. Obviously I did not mean to overlook the women, but I recognized too late the limitations of the synagogue records.

Outside sources could restore their identities, but what about their yiddishkeit? Where else could I look to put these missing women back into the narrative of their beloved community? The documentation of Lena’s husband’s continued membership suggested that she remained involved with the community, too, but Clara seemed to have disappeared until she was buried in the cemetery in 1925. What was the shul to her in the intervening decades?

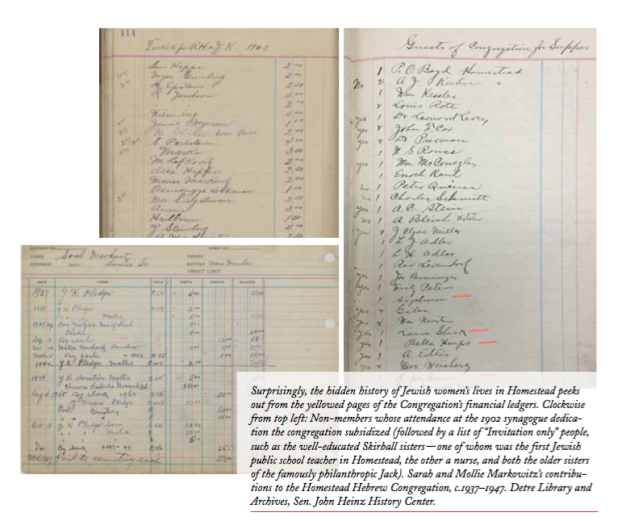

As a technology executive, I had striven for a paperless existence, but in my new life as a historical researcher, I was drowning in paper. Gone were the large teams of specialists I had once managed: day in, day out, I faced the crumbling pages alone. But my digital experience had taught me how to master large data sets, which eventually gave me courage to face the tens of thousands of handwritten entries in the synagogue’s financial records. A few months after the lecture, my efforts were rewarded in stunning fashion. In the oldest ledger book, I found Clara, buying High Holiday tickets annually! Most such entries, naturally, were listed under the men who paid on behalf of their families. But Clara wasn’t the only woman who had no man to pay for her. The laborious work of reviewing the ledger gained me the names of a handful of other single women, the only traces of whose piety were these financial ledger entries.

The presence of one of these women came as a big surprise to me. My newspaper research had acquainted me with another single Jewish woman in Homestead at that time, Rosa Heilbron (1857–1917). Unlike the Markowitzes and Segelmans, neither she nor her husband had played a role in the formation of the community. He was an established dry goods merchant, she his much-younger second wife. In 1892, a year after they moved to Homestead from Philadelphia, she asked him for permission to travel to Germany—ostensibly so her parents could meet their two year-old daughter, but in reality to escape him. She couldn’t forgive his treatment of her when she was pregnant, and had grown to resent serving his grown sons. Her prolonged absence made the family “the scandal and talk of the neighborhood.” After their very public divorce in 1893, during which the judge agreed that her husband had “no reasonable conception of how a wife should be treated,” Rosa was left to raise her daughter alone. Under usual circumstances, a German Jewish woman like Rosa would have kept aloof from Eastern European Jews, like those who comprised Homestead’s Jewish community. And yet Rosa Heilbron also bought High Holiday tickets every year! What did the shul provide her?

My success with these financial records encouraged me to spend time with other records I had initially deemed unpromising. I was rewarded with spotting Clara, Rosa, Laura, and Bella in the list of people invited to the dedication dinner as guests of the congregation. Their fellow invitees were the leading non-Jews of Homestead and the leading Jews of Pittsburgh. The inclusion of these women’s names is the strongest acknowledgement I have of the esteem in which the congregation held them.

Ironically, these women on the margins—a widow, a divorcée, and a pair of unmarried twenty-somethings—fared better in the synagogue records than the majority of Homestead’s women, like Lena and my great-grandmother, whose husbands stood for them. Married women are almost never named as individuals in these records; in most cases I can only infer their presence. Tickets, tsedakah, and invitations amount to a very thin picture, but at least they are evidence.

The counter-balance to male-created records from a male-led organization is for a female-led counterpart to tell its side of the narrative. The Ladies’ Auxiliary did not form until 1905, 11 years after the synagogue, when the third and final woman named in Grossman’s his- tory arrived in Homestead —his wife! Esther Ecker Grossman (1880–1950) had taught public school and Hebrew school on the Lower East Side for 10 years before marriage disconnected her from her family, friends and profession, with no outlet for her remarkable talents and intellect. It’s no coincidence that when the second Kishinev massacre took place just weeks after she arrived in Homestead, she became the first president of the new women’s organization founded to help the survivors. Two years later the sisterhood initiated the town’s Sunday school, and she was its first teacher. From the beginning, as the sisterhood later wrote, they “spurred the growth of sociability in this community.” It must have been an especial boon to women like Rosa and Clara, who joined early on. The group continually “[raised] funds to help support the Congregation’s many projects,” giving additional purpose to married women like Laura, also a past president. Intriguingly, a few of the presidents were women whose husbands appear nowhere in the synagogue records.

As I got to know Clara, Lena, and Rosa, the irony of my having set aside success—of a sort they (and even their sons) could have never imagined—just to tell their stories did not elude me. But it was Esther who made me more grateful than I had ever been for the blessings that had come my way. She was the only woman I encountered from the community who consistently used her maiden name. When her son was nine, she tried and failed to resume teaching public school. Esther and her husband’s private correspondence, which their granddaughter shared with me, presents a wrenching picture of a woman trapped. Esther’s energy and outlook feel familiar to me, as do her temper and frustrations. I can only imagine what she would have been with the opportunities I’ve had. I shudder to think what I would have been had I felt the force of the same constraints.

Unfortunately, only one minute book and one cashbook, together covering 1945–1961, give me any insight into how the sisterhood women saw themselves. The group’s history emerges from the synagogue’s financial records tallying their significant fundraising, decades of newspaper publicity capturing a decent slice of their activities, and board meeting minutes summarizing a few critical junctures when they intervened to try to make the synagogue more welcoming. In the end, though, there is just not enough surviving sisterhood material to balance out the male-dominated narrative of the synagogue.

I keep returning to the synagogue’s financial records to find women whose deeds are recorded nowhere else. From the decades of donors, one pair of women stands out in particular, a mother and daughter, Sarah (1867–1947) and Mollie (1886–1972) Markowitz. Sarah’s husband, Max, was “a restless creature” who left his family to move to Florida in the late 1910s, his granddaughter Helen later recalled in an interview preserved in the archive. Of his and Sarah’s three children, one daughter died in 1919, leaving two children, and their son lost his wife in 1929, leaving three more. Together Sarah and Mollie raised four of the five motherless children through the worst of the Depression.

Before Max left, Sarah’s life was much like Lena’s, but Mollie had had the chance to be something more. “She was a very bright lady,” Helen remembered. The drug company that employed her had wanted to send her to college to become a pharmacist, but “she couldn’t do it. She had a mother and two children that she was responsible for.”

A household of bereaved children raised by an abandoned grandmother and a thwarted maiden aunt sounds gothic, but they made it a happy place. “My grandmother…was a very sweet person,” Helen recalled. “She was a doll. And they were unusual people, both of them. My aunt never —she did everything for everybody —she never said, ‘I did this for you’ or ‘I gave that to you’. That’s the kind of people they were.”

The synagogue records complement Helen’s memories. For me there remains something warmly reassuring about seeing Sarah’s and Mollie’s names recur in the financial ledgers as they made their annual Yom Kippur pledges together, then Mollie alone, then Mollie and Helen together. Here was the quiet devotion of women who never neglected the synagogue even as they stretched their resources and their hearts time and again.

I think of Mollie’s example often. My cherished role as Tante Tammy to my nieces has grounded me through these years of transition. Mollie’s sacrifices remind me what it really takes to live a worthwhile life. For the little I have gotten to know her, I am grateful to have learned from her.

Clearly I am unable to resist the temptation to put myself in dialogue with all these women. When I relish my good fortune to have been born a century later, they urge me to make myself worthy of my privilege. When I feel hopelessly inferior to them, they show me that the values by which they lived—family, community, tradition—still exist, even if their force has diminished over time. And when I coax lessons from the scant traces of their lives, they make me wonder if my own life could stand up to the same scrutiny. After all, to them, the quest for self-actualization that brought me to Pittsburgh would have been unthinkable, even unforgivable in their day—to the women as well as to the men. And yet, bounded by gender, religious, and socioeconomic barriers I’ve never encountered, they found their own sense of purpose.

In 1898 Sarah Markowitz’s mother, Goldie Schwartz, was the first burial in the cemetery that was established too late for Clara’s husband. Four women whose names I will never know performed a sacred act of lovingkindness in preparing her body for burial. Six decades later, when vandals smashed her original gravestone, Mollie had a new one erected. Mollie’s loving kindness preserved her grandmother’s name to this day.

Most historical research is a rescue operation, whether assembling a narrative from fragments or finding meaning in the forgotten. The story of Homestead has been told often, because the famous 1892 strike made it a locus for historians. Now the story of the town includes the long-overlooked Jewish community that played an integral role in daily life, and Betty’s question brought forth the more elusive half of that story. As I continue working, I must listen for all the still, small voices not only in the synagogue records, but also in the broader historical record, to produce a truer result, a mix of the grand deeds and private lovingkindness that wove people together in the common goal of perpetuating their values.

When I started, I didn’t know any of this—the people, the deeds, or the loving- kindness. What glimmered in my father’s stories about Bernhardt was the sense that it mattered to know from what and whom I was descended. Learning the grand deeds, to be sure, has been the adventure of a lifetime, but understanding the individuals in the community, especially the people most like me, has been transformative. I’m still sitting with many of the same questions about myself with which I began —like whether my future path in life is history, technology, both, or neither; and how to be a good daughter, sister, tante, friend, community member, and Jew. But I’ve gained unexpected wisdom about how to approach them, and companions for the journey.

As Betty’s question implies, history needs to be relatable to be useful. We absorb its lessons best when we can find a personal entry-point to the unfamiliar. For my efforts to mean anything to any of us, they have to incorporate something of all of us.

Tammy A. Hepps is documenting Homestead’s Jewish community at HomesteadHebrews.com.

- 1 Comment

Please wait...

Please wait...