Tag : patriarchy

January 25, 2021 by Sarah M. Seltzer

Amy Coney Barrett and Me

As the world watched Amy Coney Barrett on display in the Senate judiciary hearings, I practically heard the sound of bewilderment erupting in viewers’ heads. It’s like the noise that your Waze makes when you make a wrong turn and then she has to adjust her entire plan. It’s that scratchy sound of reconfiguring.

The disconnect has to do with the realization that Coney Barrett has two sides. She is on the one hand a smart, competent career woman, and on the other hand also a voice for repressive patriarchal ideas.

But she is hardly alone. We don’t need to go all the way back to Phyllis Schlafly to find examples of WPPs—that is, Women who Protect the Patriarchy. We have plenty of examples of women like that today. I’m not just talking about the women on the public stage like Sarah Huckabee Sanders, Kimberly Guilfoyle, or KellyAnne Conway, women who have dedicated their public-facing careers to being mouthpieces for patriarchal power.

No, I am referring to a different dynamic. I am talking about women for whom the patriarchy is personal. Women who live it while defending it. An Orthodox Jewish woman, for instance, maybe the head of the brain surgery department at a hospital but accept that she doesn’t count in a minyan and her voice can never be heard in public. She may even be a brilliant musician while accepting the reality that she cannot sing in front of men, or an outstanding athlete who would never run in anything other than long sleeves and a skirt.

I know this stance well, because I lived it. I was expanding my horizons beyond what my female ancestors did—getting an education, working, earning money, speaking out—while at the same time finding my place in the women’s section behind the partition. Keeping my shoulders covered. Participating in ritual practices where I did not count and my voice could not be heard. My head was making that reconfiguring noise but it took me a while to notice the sound, or to figure out what it was saying to me.

It makes sense: pushing back against your community and everything you’ve ever known often comes at great personal cost. Women everywhere pick and choose our battles. Look at how liberal institutions—women included—have tried to sweep #MeToo incidents under the rug over time. All women are in some kind of negotiation with the patriarchy. None of us has fixed our worlds yet, so we all choose to shut out the noise.

The issue Coney Barrett’s hearings evoked, though, is that the stakes are greater when women who are protecting the patriarchy enter leadership. Then, the contradiction can take a sinister turn. Religious women can use their newly acquired power to keep other women in their place.

Coney Barrett especially reminded me of learned women like yoatzot halakha, women halakhic advisers, who are breaking barriers while using their platforms to protect patriarchal Jewish practices. Yoatzot have been among the first women allowed to take a role that for generations was the domain of male rabbis—advising religious women on ritual immersion and halakhic menstrual “purity.” No matter how you try to parse these laws or how many books are written about the “benefits” of these practices, there is no way to escape the fact that they are based on ideas that are terrible for women: that the purpose of our sexual lives is to procreate, that our menstruation makes us “impure,” that there is no such thing as non-sexual physical contact between men and women, that men cannot look at their wives without wanting sex, and that women’s most intimate body care is under the purview of rabbis. For generations, women have been showing their stained underwear to rabbis to rule about whether they could have sex with their husbands. The yoetzet position brought a welcome change: women with questions about their “purity” could at least show their underwear to a woman instead of a man.

On a closer look, though, you will often hear learned women insisting that they are not making actual rulings but merely acting as vehicles for men, the genuine voices of Jewish authority. Like Coney Barrett, they are exercising “judgment,” and “power” but only to support a sexist structure.

I grew up with female gatekeepers. The Rebbetzin in my post-high school seminary who taught us that head covering was a law brought down from Moses at Sinai. The teachers who monitored the lengths of our skirts, who reminded us that we were not “obligated” to pray mincha because we were just girls. The nice young teachers who, in twelfth grade, took us on an exclusive and exciting field trip to the local mikveh, to school us in getting ready for sex in marriage. As if ritual immersion is all you need to know about sex. And then years later, the local Rebbetzin who gave me “kallah classes” that traumatized me in ways I could not articulate.

It is hard to break away from the patriarchy, but even harder when you’ve been indoctrinated by women, women who appear warm, and speak about meaning, connection, tradition, and of course God. I call this Indoctrination with a Pretty Face.

But female gatekeepers can also indoctrinate with force. My mother aggressively groomed us—my three sisters and me—for a life of servitude as wife and mother, and as an object that was pleasing to men. It wasn’t just my clothing, my body, my face, and my food that were managed and monitored. It was also my words, my behavior, my demeanor. A girl who ate too much, who spoke too much, or who stayed seated at the Shabbat table instead of serving, was bad. A girl who challenged her father’s ideas, who ate before her father ate, or who dared get up from the table before the father declared it done, was worthy of disdain. Embarrassing.

All this was to prepare us for marriage. “Behind every successful man is a woman” were words that we lived by. And yet, even though we were taught that women’s open ambition was ugly, we were encouraged to get an education. The same way we were told we must get a driver’s license, as a kind of protection, but we were never expected to drive. Women’s driving was considered unnatural! My father mocked women drivers, including his daughters, and would never get into the passenger seat when a woman was driving. Nevertheless, my mother ensured that we got licenses, just as she wanted to make sure that we all got a Bachelor’s degree, and even a part-time job if we insisted. It was a back-up plan, not to be confused with a career. I mean, the idea of one of the daughters becoming an independent woman was almost as appalling as becoming fat.

Somewhere in the back of my brain, hearing all this, there were screechy sounds trying to get my attention, but they were blocked by messages that we had the secret to women’s success. Plus, once you pay attention to the screechy sound, once you start to question the premise of your way of life, well, the whole thing can come down like a house of cards.

That is what happened to me, though the process took 30 years.

For a very long time, the idea that this whole identity was in conflict with itself was too hard to unpack. So I took down little pieces, one at a time. Took off my hat. Started sharing roles at home. Pursued a doctorate. Made kiddush. Sat down while my husband vacuumed. Fought for agunot. Added Miriam to the Seder. Drove while my husband sat in the passenger seat.

But the thing is—and here is where it gets tricky—even while I was sorting it all out internally, externally I was still acting as a megaphone for the patriarchy. I taught religious high school girls, spitting out the same language that today I find intolerable, rhetoric about the beauty of women’s modesty, the wisdom of the halakhic system. Once when a friend of mine shared with me that she had stopped going to the mikveh, I reacted with horror. She still reminds me of that, just for fun.

One day in my sophomore year at Barnard, I was in a lecture hall listening to a class about gender and politics. In a discussion about the evolution of ideas about women and child care, I raised my hand and said, “But everyone knows that children need their mothers. Everyone knows that a child who grows up in daycare is going to be messed up.”

You can imagine the uproar. People who know me today probably don’t even believe the story. But I came from a very different place. I could have continued on my path. Perhaps had things been smoother for me, I would still be there. I think that it is very possible that I could have been an Orthodox version of Coney Barrett. One of my sisters is a yoetzet halakha. Another sister wanted to be a doctor, but did not go to medical school because she kept saying (as I did that day in Barnard) that a woman cannot be a doctor and a good mother. Sometimes I would say to her, ‘Just do it, just go to medical school.’ And she would yell back at me, ‘I don’t need any of your feminism!’ Our conversations never ended well.

Today, we are no longer on speaking terms. It was my choice. And yet my sister’s story is also my own. The messages she got are the same ones that I got. Marry early. Have lots of kids. Be a good mother. Dedicate yourself to everyone else. Oh, and do all that while being thin, pretty, perky, happy, smiling, and servile.

Had I not been unhappy with my life, I would have stayed in that world. I challenged what I was living with not because it didn’t make sense but because I was being emotionally and sexually abused. And even despite that, I tried to make it work for a long time.

It is not hard for me to imagine how a woman can be both a career-go-getter and also a defender of her religious patriarchy. In fact, these personality traits may even go together well. Religious women are often good students—smart, diligent, hard workers. And not even just religious girls. It takes a lot to manage the kinds of lives that working mothers of big families manage. It’s a lot of organizing and thinking ahead, attention to detail, multi-tasking, and problem-solving. To wit, in Israel, Haredi women are considered outstanding employees. They tend to be efficient and punctual, they get a lot done in a small space of time, they do not stand around drinking at happy hour, and they are reliable.

Maybe it’s no wonder women like Coney Barrett go far. In places where diligence is rewarded, religious women are well suited. You don’t always need to be creative to get ahead. You sometimes need to do what is expected. That quality fits in quite well with being an obedient religious woman. Her behavior at her confirmation hearings reinforced that impression—she hardly articulated any independent thought, and maintained a resolve that enabled her to get through the grueling process without getting her hands dirty or ever sharing a single personal belief.

At the end of the day, Coney Barrett was well-rewarded for her performance as the perfect patriarchal woman. She demonstrated a deep and powerful reason why women—even smart, thinking, self-driven women—sometimes become the great protectors of the patriarchy. And that has to do with what they get out of it. For them, the system works. Not only does it work, but it offers compelling rewards.

You know where to go and what to do all the time. And while a house full of kids is a LOT of work, it is also at times comforting in its busyness. Predictable trips to worship are vital for so many people—less because of prayer and more because of community. Coney Barrett may love her “People of Praise” group where her highest position as a woman might be “handmaiden” as opposed to “leader” because it gives her all the same kinds of benefits that women get in Orthodoxy—community, belonging, identity, friends, structure.

Succeeding in the patriarchy offers what Viktor Frankel argued may even be more powerful than love: purpose. Gender equality is a nice idea. But then there is what really drives us.

Not all of our choices are consistent. I hear accusations in feminist circles all the time. You cannot be both a feminist and a mother of lots of children. Or a feminist and financially dependent on a husband. Or a feminist who gets plastic surgery. Or a feminist and mother of soldiers. Or a feminist and a Zionist. Perhaps all of us, in some way, are gatekeepers for parts of the patriarchy. Maybe it’s unavoidable. After all, the patriarchy is the very water we swim in. But in that water, we still have choices. Coney Barrett made choices. My mother made choices. And I made choices.

Yet if our personal choices are private, once they become public stances, it is a whole different game. If Coney Barrett chooses to embrace patriarchal lifestyles—such as her participation in “People of Praise”—she has every right to be in that place. But once she is a Supreme Court Justice, then she is not just a woman in conflict. She has ironically broken a glass ceiling, but only to use her position to inflict some great harm on other women. If the Supreme Court knocks down Roe v. Wade or cancels birth control coverage, then Coney Barrett becomes a damaging agent of the patriarchy. It doesn’t matter that she happens to be a woman.

Photo: Kai Medina (MK170101 via Wikimedia Commons)

Dr. Elana Sztokman is an award-winning author, researcher, educator, and activist.

- No Comments

October 27, 2020 by Elana Sztokman

Amy Coney Barrett and the Women Who Uphold the Patriarchy

As the world watched Amy Coney Barrett on display in the Senate judiciary hearings, I heard the sound of bewilderment erupting in many people’s heads. It’s like the noise that your Waze makes when you make a wrong turn and then she has to adjust her entire plan; it’s that scratchy sound of reconfiguring – like, something here just does not compute.

The disconnect has to do with the realization that Coney Barrett has two conflicting sides to her persona. She is on the one hand a smart, educated, competent career woman, and on the other hand also a voice–and now, a powerful force–for repressive patriarchal ideas.

- No Comments

May 28, 2019 by Chanel Dubofsky

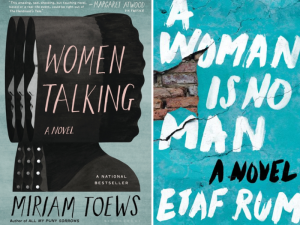

Female Rebellion Challenges Patriarchy in Two New Novels

“Revolutions don’t come from a place of happiness,” writes Etaf Rum, in her debut novel, A Woman is No Man. The narrative flips between two, sometimes more, perspectives—Isra, a Palestinian woman who leaves her home in the early 1990s to marry Adam, a man she has met only once, and move to Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, and Deya, Isra’s oldest daughter, navigating through her senior year of high school in 2008, while trying to convince her grandparents that she should be able to go to college instead of getting married. It’s a story of insularity, brutality—and the redemption that can come from women’s quiet revolutions.

“Revolutions don’t come from a place of happiness,” writes Etaf Rum, in her debut novel, A Woman is No Man. The narrative flips between two, sometimes more, perspectives—Isra, a Palestinian woman who leaves her home in the early 1990s to marry Adam, a man she has met only once, and move to Bay Ridge, Brooklyn, and Deya, Isra’s oldest daughter, navigating through her senior year of high school in 2008, while trying to convince her grandparents that she should be able to go to college instead of getting married. It’s a story of insularity, brutality—and the redemption that can come from women’s quiet revolutions.

Women Talking is the latest novel from Canadian author Miriam Toews (an actual Canadian informed me that it’s pronounced TAYVZ), about a group of women discussing what action to take after coming to the realization that they, as well as their daughters, have been raped by men living alongside them in Molotschna, their isolated Mennonite community somewhere in South America. August Epp, a young man who has recently re-entered the community after his parents were excommunicated, is the notetaker for the women, who can neither read nor write. The novel chronicles the decision-making process (the options are Do Nothing, Stay and Fight, or Leave), and the conversation grows steadily tenser when the women learn that one of the rapists is returning to the community.

It’s easy to draw lines between these novels and the current state of affairs in the world—there’s even a “not all men” moment in Women Talking. These are books about patriarchy, religious and cultural, and how women suffer while the boot is on their throats. Naturally, both these books are attracting major attention in 2019—especially from female readers and critics—as abortion bans and #MeToo stories sweep the country. It’s important to acknowledge how frankly the writers address patriarchy:

- No Comments

January 6, 2017 by Joshua Wolfsun

The Mainstream Misogyny of the Nice Jewish Boy

Often, he’s mentioned with a wink, a smile, and a tongue planted firmly in cheek. But almost as often, he’s discussed with seriousness. He comes up when the niece is planning to marry a Protestant, a Catholic (worse), a Muslim (god-forbid!), or any other manner of goyish brute. He is everything a parent would want for their daughter. He is, of course, straight.

Thoughtful, studious, sensitive, successful, and a caring provider, he is the opposite of threatening. He will always be there with a funny joke, an understanding glance, and the utmost respect for his parents and yours. He is made of better stock than the gentile suitors, and it shows. He is the man, the myth, the legend: the Nice Jewish Boy.

- 2 Comments

December 8, 1976 by admin

Beating Patriarchy At Its Own Game

Besides being “the people of the book,” the Jews have been, at least up until now, a people of the family. The stories in Genesis, that first remarkable book, begin to tell us the history of the Jewish family. These early Biblical stories, rather than being sentimental sermons exalting the joys of Jewish family life, regard the family in a remarkably sophisticated and harsh light.

These early stories shed considerable light on the role of Jewish women living in a male-dominated family setting.

Rachel and Leah are the classic women within a patriarchal society, and their struggles for security, love and meaning are dependent on their husbands. Theirs is the story of “have nots” fighting with each other for the approval of the “haves”: Rachel fights with one traditional female weapon, her beauty, while Leah fights with the other, her fertility. Throughout, they undercut each other, whine and fret, and it is hard to find a less attractive twosome anywhere in the Bible.

By contrast are Lot’s daughters who after Sodom and Gomorah have been destroyed, fear they are left alone on earth, with only an ineffectual father. The two sisters plan together how they will people their world. With remarkable sibling harmony, rarely seen in Genesis, they plan together. They get their father drunk; each then takes her turn lying with him; each gets pregnant, and each satisfies her mission. What is different about these women from the rest of the females in Genesis is that they are totally isolated from their society; they are setting up whatever brave new world they can construct and they are not bound by any traditional female role.

These two pairs of sisters are minor characters, compared to Rebekah. She is the most important and impressive archetype of wife and mother, and illustrates the complex method used by a strong and intelligent woman to cope with Jewish patriarchal society.

Rebekah is clearly no insipid ingenue; she acts, rather than being acted upon, and her actions are vigorous and successful. She talks directly to God, and is answered by Him, rather than checking through her husband. She is no long- suffering stoical martyr, for when she is pregnant with Esau and Jacob, she complains loudly and angrily to God that she cannot bear the pain of the two fighting in her womb. God respects her enough to explain the reason for this and gives her a prophecy of what will come.

Two nations are in your womb Two nations shall issue from your body But one people shall surpass the other and the older shall serve the younger.

There is no mention that Rebekah told this prophecy to Isaac.

The story of Rebekah’s relationship to Isaac disturbed me, when I was growing up in the ’50’s, at the height of the “feminine mystique.” The story is of a strong woman tricking her older, weaker, blind husband, and it is not a pretty one. In fact, we can see her easily in modern dress as the pushy Jewish mother and wife, who dominates and manipulates her man, “wears the pants,” and is the “real power.” Wary and contemptuous of this kind of woman, we label her “castrating.” The Rebekahs of the world make us feel uncomfortable in a different way than the Liliths. Lilith is forced to leave Adam and the garden because she is not male-defined, and refuses to play within the system. Rebekah, on the other hand, is an absolutely traditional wife in a situation that her strength and intelligence tells her is intolerable.

Before Rebekah is even introduced in the Bible, a terrible event has taken place. Abraham, in order to show his devotion to his God, has taken the beloved son and allowed him to be offered as a human sacrifice. This son, Isaac, who will become Rebekah’s husband, was a miracle child born to Sarah, Abraham’s wife, long after menopause. Isaac is the only child she ever conceived, although Abraham has fathered a child by her maidservant. Isaac is Sarah’s joy and raison d’etre. She fights like a tiger for him, even banishing Ishmael, Isaac’s half-brother, in order to protect him.

It appears that Sarah’s marriage has been good. Abraham loved and respected his beautiful wife. Sarah, the first of our foremothers, is presented as a beloved, strong, jealous, possessive woman, who is no shrinking violet.

Yet, at the end of a long and loving marriage, when Abraham, the father of Judaism, is tested by his male God and asked to sacrifice his son, the mother is not even consulted! It is in this omission that Sarah’s powerlessness becomes clear, despite the fact that through her sheer force of personality and beauty, she seems to have exerted considerable unofficial power previously. (It is interesting to note that the Soncino Chumash offers a commentary to the effect that Sarah actually died of the shock of finding out that her son had almost been sacrificed.)

When Rebekah marries Isaac, Sarah is already dead. Isaac is grieving for his mother, and is “comforted of her death” by his marriage to Rebekah. No doubt, Rebekah has heard about Sarah’s strength and beauty from her husband, but she has also heard that, in the most crucial decision ever made concerning Isaac, Sarah was not consulted. Rebekah, like Sarah, is very beautiful. (The beauty of the matriarchs is stressed in Genesis, except for “Leah of the weak eyes,” who pays a heavy price for her unattractiveness.)

Rebekah, like Sarah, has very definite ideas about her children, and like Sarah, she is a tiger protectress. Like Sarah, too, she has no official power, and so when the crucial decision is to be made about her two sons (in her case, it involves the giving of a blessing to only one child), she knows she also will not be consulted.

But Rebekah is an extremely intelligent and resourceful woman, and she has an advantage that Sarah did not have; she has the knowledge of what happened to Sarah! Rebekah is the first Jewish woman who forces herself into events that she is not supposed to be part of. She will not follow Sarah and die of sorrow when she finds out what her husband has done with her favored son, Jacob. Rather than be victim, she will play director.

Her first problem is lack of information. Sarah was not informed, but Rebekah will be. And so she does the first devious act that begins to make the reader uncomfortable: she eavesdrops on her husband. The focus on the Biblical reporting is on Rebekah’s eavesdropping. What is not mentioned is that Rebekah would have had no reason to eavesdrop had Isaac not withheld from her the crucial information as to what he was going to do with her sons. The modern analogy is blaming a wife for sneaking a look at her husband’s bank accounts to see how much money the family has.

Rebekah must also contend with the fact that her older, somewhat senile husband, because he is male, has the power to give the blessing. The point of view in Genesis is extremely interesting. The text seems to indicate that it is Rebekah, rather than Isaac, who has the correct perception as to which son is the appropriate one to receive the blessing and build the Jewish people. It is Jacob, the younger twin brother, the introspective tent-dweller (Rebekah’s favorite) rather than Esau, the crude, impetuous hunter (Issac’s favorite) who is destined for greatness.

Rebekah, through her eavesdropping, hears that Esau has been sent out to get some venison, and, on returning, will receive the blessing. Rebekah now has a number of choices, familiar to wives in a patriarchal society. She can be straightforward to her husband, and hope he will listen to reason. She can try to use the force of her personality to bully, wheedle, charm and convince him that Jacob is the more appropriate recipient of the blessing. From what we know from the text, these two approaches would have failed, for Isaac is devoted to Esau. What Rebekah then does, of course, is work out an elaborate trick, so that her husband will think that Jacob is Esau, and give him the blessing.

Robert Graves and Raphael Patai write, in Hebrew Myths, that the

. . . Jews of rabbinic days . . . held that the fate of the universe hung on their ancestor Jacob’s righteousness as the legitimate heir to God’s promised land. Should they suppress the Esau-Jacob story, or should they agree that. . . conspiracy to rob a brother and deceit of a blind father are justifiable when a man plays for high enough stakes? Unable to accept either alternative, they recast the story: Jacob was bound, they explained, by obedience to his mother, and hated the part she forced on him.

Mothers, of course, are often blamed for their children’s dubious deeds. But if Rebekah is interpreted merely as a scapegoat to relieve editors of the Bible about their patriarch, Jacob, the character of Rebekah loses its force and psychological truth. In fact, in the text, there is a real zest with which Rebekah manages events, an urgency and excitement in her actions.

After Rebekah’s trick is discovered, she continues to direct things beautifully. She tells Jacob to flee and save his life, as she knows Esau wants to kill him. She insists that he flee immediately to her brother, Laben. She then complains to Isaac that Jacob not marry a Hittite woman, and manipulates Isaac into suggesting to Jacob that he should look for a wife in his uncle, Laben’s family. She says nothing to her husband about Esau’s desire to kill his brother; she wants events to proceed with a minimum of conflict at this point, and so they do. Saving beloved males is one of the few straightforward, heroic deeds allowed Jewish women in the Bible. We have for example Miriam saving Moses’ life, Michal saving David, and Rebekah saving Jacob. Thus, a sister saves a brother, a wife saves a husband, and a mother saves a son.

In order to understand the complexity of the Rebekah story we need to look at the content of the actual blessing. Maurice Samuel, in his marvelous essay on Rebekah, aptly called “The Manager,” points out that there are actually three blessings. The third blessing, given knowingly and voluntarily by Isaac to Jacob is, according to Samuel, the only important blessing, for it is this one that mentions the continuance of the Jewish people and the blessing of Abraham, which is what the story is truly about.

My own feeling is that there is a fourth, and still more important blessing. This comes many years after Jacob has fled to his uncle, Laben. He has worked fourteen years for his two wives, Leah and Rachel, and is now eager to reconcile with his brother, Esau, hoping for forgiveness. At this point, a mysterious scene takes place. A man wrestles with Jacob, but cannot best him. Jacob is wounded, but will not let the man, who is actually an angel, go until the angel blesses him. The impressive blessing Jacob now receives is

You shall no longer be spoken of as “Jacob,” but as “Israel,” for you have striven with beings divine and human, and have prevailed.

It is at this time that Jacob becomes the major patriarch, when he fights alone, demands his own blessing, and has his name changed to “Israel.”

Where then is Rebekah and her grand scene? In retrospect, compared to the magnificence of the lonely fight between the truly adult Jacob and the angel, there is something sadly farcical about a mother dressing her son in sheepskin to trick her blind husband. The more important blessing was given freely to Jacob by Isaac, and the most important one came from Jacob’s own struggle. One can easily picture Jacob’s later embarrassment at having had his mother fight for him, and his pride in the blessing he struggled for himself.

And yet, farce turns into a certain kind of heroism when we see Rebekah’s actions in the context of female powerlessness. The clean, pure struggle of Jacob to become a leader was not open for Rebekah, but the power to change the history of the Jewish people was. For it seems clear from the story that no matter how important the later blessings were, it was Rebekah who, through her actions and interference, started the process whereby Jacob could become the patriarch and the history of the Jewish people could continue.

The Rebekah-Isaac family is not an unfamiliar one today, where the husband appears weak and ineffectual, the wife manipulative and domineering. As daughters; we have tended to feel sorry for our ineffectual fathers, and to dislike our tricky and devious mothers. But what the early Biblical story seems to illustrate is that one must look at where actual power lies, as well as at the contrast between the force of personalities. Isaac was old, blind, easily tricked, but the culture, the religion, the God, gave him the all-important and ultimate decision making. Therefore, if the woman was to assert her intelligence, her vigor, her more correct sense of what needed to be done, deviousness was called for. Rebekah was under no romantic illusion that they could “work it out together”; she understood that the deck was stacked against her, and she fought in the only way she knew how. She received no gratitude from her husband, who must have been angry, and Jacob must have been uncomfortable with the whole event. Esau and she had never gotten along, and she is left lonely, but victorious.

Women are now searching to understand, appreciate, and admire their mothers. It seems to me that a good a place to start in our search is to try to understand Rebekah’s dilemma and the way she coped with it. Trickery is the weapon of the powerless; hopefully, there will cornea time when that weapon is no longer necessary.

Mary C. Schwartz is an Associate Professor at the School of Social Work, State University of New York at Buffalo. Her article “The High Price of ‘Failure” appeared in the premiere issue of Lilith.

An address to a young student

by Gloria Och

I tried to think of a way to bless you today. The traditional blessing is: May God make you like Sarah, Rebecca, Rachel and Leah. I thought to myself: Do I really want her to be like Sarah, who, for whatever her reason, chased Hagar and Ishmael into the desert? Or, like Rebeka, who taught her son Jacob to lie to his father and to cheat his twin brother? Should she be like poor weak-eyed Leah who was foisted upon Jacob after he had worked seven years for Rachel, whom he loved? Rachel was beautiful and beloved, but, alas, she died in childbirth, and according to tradition she is spending eternity weeping for her children who are dispersed, refusing to be consoled.

There is Miriam, who loved to dance, but she, like you, had two brothers, and when she gossipped about the wife that Moses had chosen she became leprous.

Next is Deborah—prophet, military leader, judge and poet. The Bible speaks well of her, but the rabbis who wrote the Midrash tell us that she was vain in the manner of women and that she judged under the palm tree because it was not fitting for men to come to her house. God only knows what she would have done to them!

We can go on and on through the Bible and not find a single woman whose life is unscarred by a tragedy which is part of some divine plan, or whose character is presented as one we would want you to emulate.

Of course, everyone’s example of a woman who was outstanding in Talmudic times is Beruriah, wife of Rabbi Meir, a noble woman who would not disturb her husband’s Shabbat to tell him of the terrible death of their two sons. She was a scholar as well. But even her reputation is tainted by tradition; we are taught that her husband tested her by sending one of his students to seduce her. She failed the test and committed suicide. Whether or not the story is true is immaterial. The important thing is that we are not allowed to believe that even Beruriah is without flaw.

Why is this the picture presented of the Jewish woman, supposedly so revered? For one thing, the greatness of the Bible is that people are presented as humans with all their flaws, and not as saints. But, I submit, the problem is also that women didn’t write the books and, we were not the active creators of Jewish history.

Now the tide has turned. You and your friends are being educated in exactly the same manner as your male classmates, not so that you can stand up at the bimah and do exactly what they do for Bar Mitzvah. That is not a reason for opening a Hebrew day school. Our dream is greater than that! Your job now is to study our past and to chart our future. In hundreds of years from now when people study the Jewish community of the 20th Century, let them not ask about our times as we do of other periods of Jewish history, “But what did the women do?” You must help not only to write the history, but you must be an equal partner in everything that happens. It will take time for some people to accept the fact that the women of today and tomorrow are no longer in the tent, nor only in the kitchen and the home, but have accepted the full responsibility of Jewish womenhood and Jewish community.

You have a love of Judaism, you have knowledge, and you have the tools to acquire more knowledge. We hope that this book will always remind you of your years at our school and of your responsibility as an educated Jewish woman.

May you be blessed and may you always be a blessing, as you are today.

Mary C. Schwartz is an Associate Professor at the School of Social Work, State University of New York at Buffalo. Her article “The High Price of ‘Failure” appeared in the premiere issue of Lilith.

- No Comments

September 7, 1976 by admin

American Jewish Men: Fear of Feminism

I want to speak of an important choice which faces American Jewish men in responding to the feminist movement and to Jewish feminism in particular. Some things that I write may seem applicable to all men in our relationships with all women. Some may seem specifically relevant to Jewish men and Jewish women. I intend this brief article not as a definitive statement, but as a small part of an ongoing dialogue.

I am a 28-year-old Jewish man. I received my Jewish education in an assimilated, upper middle class Reform synagogue in Westchester County. Like my Jewish male friends, like all Jewish men, I was brought up, educated, and socialized to oppress women.

Of course, no one ever told me so directly. No, the messages of patriarchal society were so unchallenged and so implicit, that there was no need for anyone to spell them out. Male dominance was a reality that “everybody” accepted – or so it seemed. Within secular institutions, men were considered important, women unimportant. Within the Jewish community, Jewish men were considered important, Jewish women unimportant (or, at best, important in their place, like any good servant).

To cite only one of many examples from my own life, I was named one of eight feature editors on my high school newspaper. The other seven were Jewish women, and we officially began as equals with the same title and prestige. But, in a short time, I had assumed total control of the feature page. I wrote most of the editorials, and assigned others as I chose. I monopolized the layout process (which I enjoyed), and delegated responsibility for copy editing and proof reading (which bored me). I wrote a regular column and generally placed it in the best position on the page. Most dramatically, I managed to purge a number of women editors who did not shape up to my personal standards of competence (or was it obedience?).

All of my Jewish male friends had similar patterns of “growth” and “maturity.” One ran the temple youth group, one ran the Y.M.-Y.W.H.A. youth group, one ran the National Honor Society chapter, one ran the Senior Activities Board, two ran the sports page of the newspaper, and others ran the Key Club.

Each of us had his own little fiefdom. Each of us dominated a prestigious institution and had “his” women under his control. Each of us was learning important lessons about male supremacy, especially as it affected Jewish women and Jewish men. And the Jewish adults around us were giving unspoken blessing to these arrangements, since they duplicated nicely the male dominance of all Jewish and Christian organizations in our city. We “nice Jewish boys” were preserving a long cultural heritage of subjugating women, while at the same time we were being assimilated into WASP mores about how to “make it” as American men.

It’s been a long time since high school. In recent years, exposure to the writings and teachings of the women’s movement has forced me to re-examine my socialization as a man, as an oppressor of women. I’ve gained a different perspective on the power struggles between Jewish women and Jewish men — a perspective which may help explain why Jewish men have such resistance to feminism.

Jewish women have traditionally faced a unique and most demanding double oppression: as Jews within a hostile, anti-Jewish world, and as women within a co-optive and hostile patriarchal Jewish culture. I believe that all women have had to develop incredible strengths in order to survive their oppression.

In the case of Jewish women, a distinct tradition of strength, courage, and independence has emerged. We can see these qualities among many Jewish women whose life situations varied greatly — among Jewish women who struggled to preserve their families in the face of anti-Semitism; among Jewish women who fought to build careers as writers, artists, physicians, and the like; and among Jewish women who became outspoken political activists, such as Emma Goldman and Ethel Rosenberg.

I believe that most Jewish men are at least aware of this tradition among Jewish women. Awareness can lead to a number of responses. Jewish men could understand the current upsurge of Jewish feminism in the light of this herstory, and could struggle to understand and accept what Jewish women are telling us despite all of our fears. Unfortunately, there are other, more popular choices for Jewish men.

All Jews are familiar — much too familiar — with the woman-hating, Jew-hating stereotypes of the “Jewish mother” and the “Jewish American Princess.” When Jewish men perpetuate these vicious caricatures, it is in response to the strength, courage, and independence of Jewish women. The mature, forceful Jewish mother and the young, assertive Jewish woman are frightening figures for many Jewish men. Each represents a Jewish woman who will not quietly and sweetly submit to her “natural” “feminine” role. This leads Jewish men to brand Jewish mothers as “castrating” and young Jewish women as “bitchy.”

These epithets are crucial weapons in the arsenal of male supremacy. Whenever a man calls a woman castrating or bitchy, it is because somewhere, somehow, intentionally or not, she has threatened his power and dominance. He is telling her to shut up and stay in her place — or else. This is the message behind these vile lies about Jewish women which too many Jewish men are eager to spread. The independent, self-reliant, assertive Jewish woman (and, of course, the Jewish feminist) strikes terror in the hearts of every Jewish man, on some obvious or well-hidden level.

This backlash among Jewish men must be understood in terms of the long-standing traditions of Jewish patriarchy: the relegation of women to wife and mother roles, the refusal to let women count in a minyan (quorum of worshippers), the denial of educational opportunities for women, and so forth.

But Jewish men’s backlash must also be examined in the context of American definitions of “masculinity” and sexual politics. While Jewish men commonly fear the independence of Jewish women when it appears at home or in private, Jewish men are particularly embarrassed and resentful when Jewish women act forcefully in public situations. The key to these responses is the desire of Jewish men (and the pressure on Jewish men) to assimilate and to succeed in the eyes and the world of Christian men.

Jewish men in America — like men from other minority groups — have grown up feeling “deprived” of an opportunity to attain what is culturally defined as full manhood. Jewish men have envied the unquestioned patriarchal rights and male privileges held by white Christian men, and have felt disqualified from achieving this status because of Jewish identity. In short, Jewish men have wondered: why can’t I be treated just like any other man?

The most important definitions of masculinity in America still come from white Christian men — Jack Kennedy and Sean Connery in my adolescence, Joe Namath and Robert Redford today. In this climate, Jewish men feel uncertain of our “masculinity.” No matter what a Jewish man does — whether he graduates from Harvard, amasses a fortune, gains public office, dazzles as a movie star, excels in professional sports, or impresses (oppresses) numerous women — he can still never attain the WASP looks and cool of a Robert Redford.

Of course, Jewish men could reject the whole masculinity-proving game. We could recognize how inherently repressive, alienating, and woman-hating it is. We could attempt to work our way out of our various male power trips, and forget about demonstrating our “manhood” in white Christian terms or in any terms. But most Jewish men want full patriarchal rights, want publicly certifiable “masculinity,” and want to be equal in status and power with Christian men.

To achieve these goals, Jewish men attempt to be “real men” by showing that we have “our” women under control. We try desperately to prove to Christian men that we can keep women in line just as casually and gracefully as the Redfords and the Kennedys. For only then will Christian men respect us; only then will they consider us for equal membership in a patriarchal society.

Thus, the strength, courage, and independence of Jewish women become a particular threat to Jewish men. And Jewish feminism, as an organized political movement challenging our dominance, is even more frightening to us. If Jewish women appear “uppity” in the eyes of Christian men, then Jewish men will be viewed as weak and unable to rule our own culture. Furthermore, Jewish women’s independence might lead to direct competition with Jewish men for jobs, income, status, and power. This could easily undermine our upper hand as providers for Jewish women and children. Both on the levels of appearance and reality, Jewish women’s advances endanger Jewish men’s “making it” within a male-dominated Christian society.

I believe that Jewish feminism faces Jewish men with a very simple but critical choice. We can continue to blame all of our problems on Jewish women, whom we have power over, whom we oppress. We can continue to curry favor with and emulate the Christian men who are slightly higher than us on the ladder of power and privilege. Or we can finally acknowledge the reality of male supremacy within all of American life and American Jewish life. We can dispense with our jokes and threats and stereotypes and begin to treat sexism as a serious matter. We can commit ourselves to learning from the feminist movement and the Jewish feminist movement.

If we are to act responsibly in changing our sexist attitudes and behavior, we must begin by making a diligent attempt to listen to women. This means closing our mouths and opening our minds. It means struggling to understand women’s oppression, rather than showing off our argumentative skills. It means reading the important literature that comes to us from women writers, from feminists, from Jewish feminists. It means admitting that when a woman’s feminism angers or threatens us, it is exactly at this point that we must step back and confront our own fears.

Acting responsibly also must include a scrupulous examination of our male privileges as Jewish men. This means understanding the privileges that men have traditionally held in Jewish and non-Jewish cultures. It means understanding the specific ways in which each of us has benefited and continues to benefit from being male. And it means acting on this knowledge in order to end our power trips over women. If the concept of male privilege seems distant and unclear, this only indicates that we have a lot of reading and thinking ahead of us.

Of course, acting responsibly also means fighting against men and institutions that perpetuate male supremacy and privilege. On a political level, this means supporting feminist initiatives within the secular culture and within the Jewish community. On an individual level, it means continually speaking out against any man’s sexist jokes, looks, stereotypes, smears, and outright attacks. It means breaking male bonds, it means challenging other men, it means risking male wrath, and it often means losing male friends.

Finally, acting responsibly necessitates constant awareness that we are men and benefit from male privilege no matter what we do. This means that our voices will be heard at the same time that women are ignored, and that even our sincere actions can lead to new patterns of male dominance. The “liberated man” or “male feminist” can be just one more power play. Thus, we must never attempt to speak for women or forget who we are. We must understand and defend women’s right to space and time of their own, away from men — even supposedly concerned men — in order to freely determine their own priorities, strategies, and life choices. Sometimes, we act most responsibly by simply staying out of the way of women — and yet we cannot use this knowledge as an excuse for total inaction, for there are many situations in which we must fight our own and other men’s sexism.

I believe that these are our choices as Jewish men. And I believe that it is time for us to begin acting responsibly. We’ve oppressed Jewish women for more than 5,000 years. That’s long enough.

(I would like to thank Harlene Hipsch, Steve Nachtigall, Julie Dorfman, Amy Stone, and Shifra Bronznick for reading and making important criticisms of earlier drafts of this article. Any faults are my responsibility and not theirs. – B.L.)

Bob Lamm is a free-lance writer whose work has appeared in Response, WIN, Jewish Digest, and Morning Due. He teaches classes on “Men, Masculinity, and Sexism” and “The Politics of Sports”at Queens College, C.U.N. Y.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...