Tag : orthodox jews

January 16, 2020 by admin

Compliance

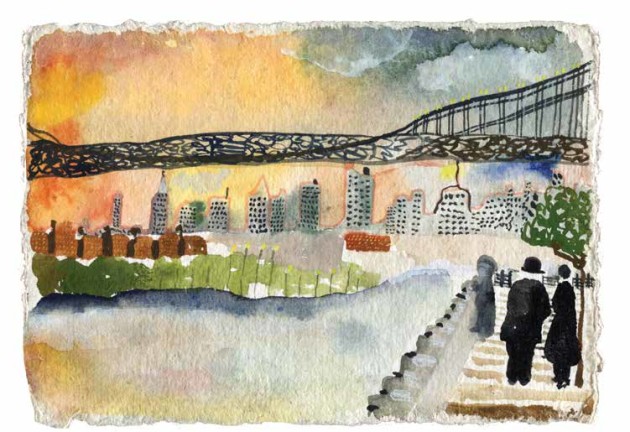

ART: SARAH WILLIAMSON, WWW.SARAHWILLIAMSON.COM

She knows the neighbors call on her because she is childless—an anomaly, a two-headed turtle in this enclave, where every woman’s accessory is a baby carriage. It is always Chana’s door they ring if they need her to watch their children, so they can run to the store for a forgotten ingredient for Shabbas dinner, if they need a light bulb changed, if they need help with the settings on their iPhones. Go ring Chana’s door. She’s not busy.

This afternoon, when she opens the door, Ruthie, her neighbor from 3C, stands there holding her baby, absently patting his diapered behind. Ruthie wasn’t one to make small talk. She immediately asks Chana for her favor. Chana hasn’t answered, and Ruthie takes the silence for what it is: a no.

“Chana’la, please,” she pleads. “You know I wouldn’t bother you if it wasn’t an emergency. I have to take Mendy to the doctor. He’s running a fever. “

Chana can’t remember if Mendy is the baby Ruthie is holding or another one of the five wild boys. She studies Ruthie in the doorway. Chewed nails, her teichel slightly skewed on her head. Always a bit undone.

“I’m sorry. I really want to help, but… .” She find herself trailing, searching for an excuse, but she doesn’t have one handy, other than the obvious: she doesn’t want to do it. “I can’t—“

Ruthie plows ahead. “It’s the girl from the news. Only seventeen. You must have heard.”

She has heard. Everyone had. It was splayed on the front page of the New York Post and the Daily News. A teenage girl, Rebecca Lichtenstein, was kidnapped in front of a convenience store on Eighteenth Avenue. All the local news stations looped the surveillance footage capturing her struggle and abduction. A man, in a dark hoodie, grabbed her and threw her in the back of a white van. She was found the next day, in a dumpster, just two blocks from her apartment, mingling with McDonald’s wrappers and Tuesday’s trash. The news reported that she had been strangled.

“I’m not the person for this. I haven’t been trained.”

“It’s often not as bad as people think,” Ruthie dismisses. “Please?” And anticipating Chana’s reluctant consent, Ruthie pulls out a yellow, Post-It note from her apron pocket. “Here’s the address. Please be there by two.

“And now, here she is, riding the F train, the yellow note in her pocket, annoyed that, once again, she gave in to something that she didn’t want to do. The train is crowded, and a group of high school girls congregate around her. One girl, holding the straphanger pole in front of her, shouts over the heads of the other passengers to another. “Anne has a crush on Matt!”

The other girl shouts back, “Shut the fuck up, Josie.”

Normally, Chana would be irritated by the use of profanity, but today she is amused hearing the teenage girl utter her old name—Anne—familiar, but not. Once she became a baal t’shuva, she decided to change her name to suit her new identity, just like Abram became Abraham, when God told him that he will be the father of many nations, Naomi became Mara, because she felt HaShem dealt bitterly with her, and Jacob became Israel, after he wrestled with an angel. A linguistic legerdemain. And she figured if Clark Kent could become Superman, Bruce Wayne, Batman, and Ralph Lifshitz, Ralph Lauren, Anne could transform into Chana.

She was in her sophomore year at California State University, Chico, when she was required to a take a religious studies course. She signed up for what looked easiest: a Jewish Studies class. They studied the mysterious, Zohar, with its esoteric discussion about the nature of existence; they read Maimonides’ philosophical Guide for the Perplexed. And that one class led to another, until she switched her major from English to Judaic Studies. She attended Shabbat services at the Hillel House, but that was mostly to flirt with a frat boy who was a terrible lay, but who broke her heart nonetheless.

Then, she was accepted on a Birthright trip to Israel, where she prayed at the Kotel in Jerusalem. She loved the stillness, the other worldliness of Shabbas in Jerusalem. The mastery of time and space that Shabbas required.

But it was after she had taken the Snake Path at four in the morning and climbed the rocky terrain up the side of Masada, she knew, like the zealots, there would be no turning back. Her neshama, her soul, was on fire, and her life would take a different trajectory. She watched the sunrise over the Judean Hills, the pastel orange blanketing the desert, and it was then she recognized that everything about her would be discarded. Anne was no more.

When she returned to the United States, she sat with her parents at a Starbucks. She told them the good news: she was getting married to a young man who just completed his rabbinical degree, who didn’t care about her secular background.

“You know,” her mother began, and Chana could tell that she was measuring her words. “You’ll have to support him while he sits in the yeshiva studying.”

“It’s an honor to be married to a learned man,” Chana countered, and she hated how defensive she sounded.

Exasperated, her mother could not restrain herself. “Anne, why would you choose to be so provincial?”

At that moment, she was hurt, feeling unsupported and raw, so Chana lashed out bitterly, “Because I want a life that’s not as banal as yours.” Her mother recoiled, and Chana regretted those words as soon as they were spoken.

It’s as if she had released feathers from a pillow in the wind, and she now had the impossible task of having to retrieve each and every one. It could not be done.

The subway doors slide open and the cold air of the platform sweeps in. Chana elbows her way through the crowd and gets off at the Avenue X station, walking down the subway stairs to the street.

She passes a couple, their happiness creates its own heat, like the tenderness she feels for Aryeh. He is a good husband, always wanting to make her happy. Many men in this religious community would not have married her; she is tainted goods. Certainly, no virgin. While there is praise for the baal t’shuva, the one who returns, Chana experiences trepidation, a fear that she might slip off the path, like this is a fad, similar to twerking or ordering Cosmopolitans like the shiksas on Sex in the City.

And when, after four years of trying to have a baby, and consultations with rabbis and doctors and more rabbis, and Clomid cycles, and monitoring basal body temperature, and checking if she’s ovulating by noticing that her cervical fluid resembles egg whites, she learned that she could never have her own child. She told Aryeh that she would divorce him, allow him to create the children he deserved. And he hugged her and whispered Solomon’s words, first in Hebrew, then in English, “’I am my beloved, and my beloved is mine.’ You are mine forever, Chana. Nothing has changed.” She loved him more that moment than at any time in their marriage, and that night, after they returned from their final visit with the fertility specialist, they both wept and made quiet love. The revelation was finite: there would be no children unless HaShem opened up her womb as he had Sarah’s; they would live a childless existence. No carriages, no overstuffed diaper bags, no birthday parties, no skinned knees to kiss and bandage, no weddings to plan. Her husband grieved by increasing his Torah studies, and she replaced the empty ache in her arms of wanting to hold an infant by working, by perfecting her craft of being a sheitel macher, a wig maker. She was skilled in all aspects of hair design: styling, cutting and dyeing—a rarity, and the women trusted her to fix their sheitels for whatever simcha they were getting ready to celebrate.

Once again, Chana takes the note out of her pocket to check the address and sees that, yes, this is it, Gutmann Memorial Chapel. She hesitates, taking a deep breath. She grabs the ornate, heavy door handle, and she pushes her way into the carpeted lobby. Dated dark wood panels on the walls and an aging grey carpet.

An older man, wearing a blue velvet kippa, pudgy in his cheap suit, rushes out of a side office. Her stomach lurches. She thinks she can smell death, but she’s not sure what death smells like.

“May I help you, Miss?”

Confronted, she yields, speaking quickly. “I’m Mrs. Aaron.”

He stands silently, staring at her, seeming to want more information. She feels compelled to continue.

“I said I would help with the tahara today,” she explains, clutching her purse, a wave of nausea, the one she feared would overtake her, starts rising in the throat.

The man takes her in, and he pulls the straining jacket around his midsection. “Follow me,” he says, and she walks behind him, embarrassed that she notices that he has a large ass; his hips wide like a woman’s.

They walk in silence and then he opens a door. It looks to Chana like a surgical suite. Sterile steel tables, shelves with bottles of alcohol, Peroxide, cotton balls, and Q-Tips. A pile of white sheets, neatly folded on a lower shelf, and, to the right of the doorway, an empty pine box with a hole in the bottom—the girl’s coffin, not yet filled.

“Welcome,” Mrs. Rabinowitz greets her. Chana recognizes her from the neighborhood, and from shul. She is short, borderline midget. Chana notices that, as always, Mrs. Rabinowitz’s bleach-blonde sheitel seemed curiously out of place on her head. Farrah Fawcett’s hair on Danny Devito’s body. She sees Chana sway and places a hand on her shoulder. “Are you going to be okay, darling? Mrs. Rabinowitz asks.

Catching her breath, she replies, “Honestly, “I don’t know.”

Chana sits on the cold, metal folding chair, taking deep breaths. She desperately wants the water, but she does not want to drink anything from this house of death. The idea repulses her. She fears it would taste like ammonia and decay.

And it is only now that Chana the other women in the room, quietly donning their surgical gowns, arranging items on a mobile steel tray, pouring buckets of water, working in a deft, silent rhythm. She recognizes them from shul. She remembers that the tall brunette with the Israeli accent, Biela something, had come into her shop once to have her wig styled for her daughter’s wedding, but the others are relative strangers.

“I’m filling in for Mrs. Aviv,” Chana says, hoping the explanation somehow explains her behavior.

Mrs. Rabinowitz nods. “Are you feeling better?”

Chana nods. She does feel better, more stable.

“Please wash your hands in the sink.” Mrs. Rabinowitz then calls to a tall, heavy-set woman who is already ensconced in surgical garb, “Malky, please get Mrs. Aaron a gown, mask, and gloves.” Mrs. Rabinowitz turns her attention back to Chana. “Don’t be frightened,” she says kindly. “The dead can’t hurt you. Only the living.”

Chana walks to the sink and using the stainless-steel wash cup, she pours water over her right hand and then the left three times, moving her lips in prayer. Malky hands her the gloves, surgical gown and mask, and Chana dresses.

“We are going to wheel her in now. Are you ready?” Mrs. Rabinowitz asks.

“Yes,” Chana answers. She is left alone with the other women, Malky and Eli-Shevah. She knows that one is prohibited from making small talk during a tahara, so she waits silently.

Malky cuts long strips of white sheets, laying them on a tray next to a stack of white washcloths. Nearby, on a small steel bench, she sees the white tachrichim, the burial clothing.

They wheel in the gurney, feet first, and Chana sees the body draped in a white sheet, a strand of brown hair visible at the top. The girl’s body outline under the sheet is petite, her small feet only reaching the midway point of the gurney. Feet turned out, as if in First Position in a ballet class.

The women surround the body.

Mrs. Rabinowitz nods, and Malky lifts the sheet and covers the girl’s private parts with the cut sheets she has arranged for just this purpose, so they can begin to prepare her for the tahara. The women collectively shudder when the sheet is lifted, and, somehow, Chana knows that this hesitation, this group paralysis, is not what normally occurs.

The girl is naked in death as she was in birth. She was not a religious girl. Her nails are painted a deep, gaudy dark red, and her pubic area is hairless, waxed, with course stubble beginning to have grown back. On the inside of her dainty right wrist is a tattoo: three tiny black birds, in mid-flight, ascending, running from the center line of her wrist, moving upward half an inch to the left. Above the birds, in elegant, black, tiny script letters, “If you’re a bird, I’m a bird.”

Chana wonders what the tattoo means. Who is the other bird? A lover?

While tattoos are prohibited, Chana recognizes the appeal of this one. It is connected to another human being, a signifying marker of belonging.

None of them, it seems, can take their eyes off Rebecca’s neck, and the mark of the animal that is still out there hunting girls.

A few seconds pass, and still no one moves. Not meaning to speak, but unable to stop herself, Chana hears her own hoarse voice, muffled by the mask: “Rebecca is beautiful.”

Quietly reproachful, Baila corrects her. “She is Rivka bat Yocheved,” she says, and Chana realizes that Baila is right. In death, all identity reverts to The Source. Only her Hebrew name will be used from this moment in the tahara preparation, to her funeral service, to her parents’ recitation of Yizkor, to their lighting of Yahrzeit candles on the anniversary of her death, to the name that will be inscribed on her tombstone, exposed at her unveiling a year from this date. She will be remembered as Rivka, daughter of Yocheved. Like “Anne,” Chana knows “Rebecca” is gone. Rivka is all that remains. It is her unbidden transmutation. Abram into Abraham.

“Can you remove her nail polish, and then place her rings in a plastic bag? Also, please clean under her nails. There’s a toothpick on the tray for that purpose,” Mrs. Rabinowitz instructs. Malky covers Rivkah’s private parts with the sheets she has cut, and the other women start praying and dipping the washcloths in the buckets of water. They swab Rivka’s head and move towards her ears and neck.

Chana takes a cotton ball and saturates it with the remover. Then, she picks up Rivka’s right hand. Cold. The girl’s hands are exquisitely long and thin. Perfect fingers.

When Chana is satisfied that the fingernails are plain and clean, she grabs a plastic bag to place the rings. Two rings on Rivka’s right hand, one on her left. Chana starts with the right hand. A blue sapphire-like ring on her middle finger. Her birthstone? She needs to wiggle it over the knuckle to get it off. On the index finger, a silver tone oval turquoise, cabochon ring. This one is harder to remove. Mrs. Rabinowitz comes over with a bottle of baby oil, pours a little on the hand, and Chana is able to slip it off. She dries it and moves to the left hand and sees a silver thumb ring, with a swirling Celtic knot design. Chana wonders if the Other Bird had given it to her.

Mrs. Rabinowitz inspects. She gives the directive, and the women transfer Rivka from the gurney to the tahara table, a grooved steel gurney, with three seat-belt straps to hold the body in place. It is on a hydraulic lift system. With the push of a button, the body can be tilted to a standing position, making it so the water can flow over it.

Baila draws water from a bucket into a small urn and pours it over Rivka’s body.

All of them stand around her body and as the water pours, they repeat, “Tahara hi, Tahara, hi, Tahara hi.” She is pure. She is pure. She is pure.”

Mrs. Rabinowitz instructs to cover Rivka’s hair with a cap and a veil for her face. Chana stares at Rivka’s face, hold her pale beauty in her gaze.

Baila brushes her hand and whispers, “It’s time.”

And Chana places the veil on Rivka’s face. Finally, after Rivka is dressed, the women lift her, swaddle her, and place her in the coffin. Mrs. Rabinowitz closes the lid.

Chana emerges from the chapel, the last vestiges of the winter sun caressing her face; it will be dark soon and the deep cold will settle in. She walks the four blocks back to the subway, up the stairs to the platform, returning to the world of the living. In her pocket, she feels the metal ring, tracing the outline of its swirling Celtic circles with her index finger. The express train thunders by on the platform, roaring, the clatter of the wheels rolling on the tracks echoing, if you’re a bird, I’m a bird. If you’re a bird, I’m a bird. If you’re a bird, I’m a bird. Chana takes the silver ring out of her pocket and drops it into the palm of her hand. She slips it on her ring finger, knowing it will be too small for her thumb. She has to wiggle it to get it over her knuckle.

Andrea Greenbaum is professor of English at Barry University, Sundance Screenwriting Fellow for her script “36,” and author of six books, including her most recent, Jewish Women in Comics: Borders and Bodies.

- No Comments

June 27, 2018 by Rebecca Krevat

Why We’re Protesting the Orthodox Union Every Monday

Keeping Kashrut, or kosher, is one of the most central and recognizable pillars of observant Judaism. As a child in a traditional but modern Orthodox community, I was taught the importance of keeping kosher. Even when I was a toddler, I asked my Orthodox uncle if his house was kosher before feeling comfortable eating there. For our family, food products needed kosher symbols. At the grocery store, families like ours all across the country scan products for the “OU” symbol from the Orthodox Union—one of the most widely recognized and trustworthy of the kosher symbols.

Keeping Kashrut, or kosher, is one of the most central and recognizable pillars of observant Judaism. As a child in a traditional but modern Orthodox community, I was taught the importance of keeping kosher. Even when I was a toddler, I asked my Orthodox uncle if his house was kosher before feeling comfortable eating there. For our family, food products needed kosher symbols. At the grocery store, families like ours all across the country scan products for the “OU” symbol from the Orthodox Union—one of the most widely recognized and trustworthy of the kosher symbols.

The Orthodox Union is an umbrella organization representing Orthodox synagogues and communities across the United States. In addition to telling the community what foods are permissible to eat, the OU runs programs that keeps the organization deeply rooted in Orthodox communities, including youth groups and support on campus. The OU is a significant component of the blood in the veins of the Orthodox communal world.

I didn’t even realize the OU did any political work outside of their communal support until 2014, when I noticed that they had commended the Supreme Court’s decision siding with Hobby Lobby in a notorious case regarding an employer’s responsibility to provide insurance inclusive of contraception, as mandated by the Affordable Care Act. They sided with the evangelical Christian plaintiffs in that case, even though President Obama had already ensured that any company that was not comfortable paying for contraception could employ a provision so the government would pay for it instead.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...