Tag : menstruation

November 5, 2019 by admin

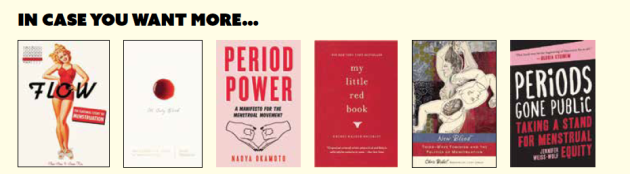

Required Reading

Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation, by Elissa Stein, offers a history of Jewish views, and some new perspectives.

Flow: The Cultural Story of Menstruation, by Elissa Stein, offers a history of Jewish views, and some new perspectives.

It’s Only Blood: Shattering the Taboo of Menstruation, by Anna Dahlqvist and Alice Olsson. Every day 800,000,000 people menstruate; why and how people around the world are now fighting back against stigma.

Period Power: Harness Your Hormones and Get Your Cycle Working For You, by Maisie Hill, bills itself as a guide for dealing with PMS, periods, and such.

My Little Red Book, edited by Rachel Kauder Nalebuff, is a collection of personal essays.

New Blood: Third Wave Feminism and the Politics of Menstruation, by Chris Bobel. An ethnographic exploration of cultural shifts surrounding periods.

Period Power: A Manifesto for the Menstrual Movement, by Nadya Okamoto, presents a call to action to destigmatize menstruation.

Periods Gone Public: Taking a Stand for Menstrual Equity by Jennifer Weiss-Wolf, explores “menstrual justice” work.

- No Comments

November 5, 2019 by admin

Period Positivity

Before you turn the page and enter a world where menstruation is a subject of performance art and hormones are being touted as the drivers of all aspects of our lives, let’s acknowledge the whiplash of living through rapid shifts regarding our hormonal selves. There was a time—well into the 20th century, in fact—when women’s concerns, be they personal or political, were considered “hysterical,” originating in the womb. Periods, like pregnancies in the Victorian era, were to be concealed and were never discussed in public.

Not only was period talk taboo, but menstrual blood itself was actually considered dangerous. Citing a 1934 article, here’s what appeared in the pamphlet Jewish Family Life: The Duty of the Woman, published by Agudath Israel Youth Council of America in 1953 and provided to Lilith by Sheri Sandler, who found it among her late mother’s papers: “a toxic substance is present in the blood serum, blood corpuscles, saliva, sweat, milk, tears, urine and other secretions of women at the time of menstruation.”

Then, as women staked claims to some share of the power and the pie in the heyday of the women’s movement, from the late 1960s through much of the 1980s, no women with any feminist cred would have wanted her behavior labeled hormonal in origin. Granted, some iconoclastic artists dabbled in painting with menstrual blood, but mostly women wanted to think of themselves as just like men, capable of advancing in the universe as long as the costume included, for a certain stratum, power pantsuits. Children at home? Never mentioned at work. A migraine because of one’s period? Not at all—merely the result of a late night working on a report. Parody aside, keep these rigid standards in mind as you think about the current evolution of “period talk.”

Interestingly, at the same time as Jewish women were eager to advance in a “man’s world” by keeping hormonal matters out of sight, there were women creating new traditions around a typical distinguishing characteristic of female bodies— bleeding once a month from menarche to menopause. (Some of these rituals for a first period or for marking the cessation of periods spotlighted in Lilith.) Jewish law is pretty specific and matter-offact about women’s periods, what one cannot do while menstruating (have sex with one’s husband) and how to determine when a period has ceased (examine one’s vaginal canal with a clean piece of cloth; if in doubt, show the cloth to a rabbi).

The idea that we’re all embodied selves had to be stashed away so women could go to law school and rabbinical school and business school without being told (as many students were as recently as the mid-1960s) that their gender rendered them unfit to occupy the classroom seats they were so obviously seated in. Today, posts on social media will announce a person’s “phase of the moon” with the same forthright conviction used a few decades ago to discuss the implications of one’s astrological sign. And as you’ll see when you look at the titles of the new books on hormones and periods, we can now safely take our bodies out of the storage unit where, presumably, they’ve been renting space for quite a while.

Enter a new era of hormonal glory—the age of period positivity.

- No Comments

November 5, 2019 by admin

Like Toilet Paper, Free Tampons in Every Restroom!

Last year when I was a senior at Brookline High School, I wrote an op-ed in the student-run newspaper about the stigma and cultural shame surrounding menstruation in our society. The article caught the attention of local legislator Rebecca Stone, who took action to combat some of the concerns I voiced in the piece. This past May, Brookline became the first municipality in the country to provide free menstrual products in every public restroom.

Ms. Stone’s response to my original article, as well as the public support for the (now passed) warrant, goes beyond anything I could have imagined. Among many things, this experience has renewed my faith in the power of storytelling.

Ms. Stone’s response to my original article, as well as the public support for the (now passed) warrant, goes beyond anything I could have imagined. Among many things, this experience has renewed my faith in the power of storytelling.

High school was also when I learned how to use stories in the service of lobbying. I had several mentors in this endeavor, and their advice was the same: Make it personal. Statistics are great for showing the big picture, but numbers are even more effective when a legislator can see a face behind them. When my peers and I visited political offices in downtown Boston and in Washington, D.C., we became comfortable telling stories about our experiences with the health- care system and sex ed in school. Even though these stories were personal, our sharing was in the service of something greater. At least for me, this completely justified any discomfort I felt.

The seeds for the menstruation article were planted when I participated in an activity for a group of campers at the sleep- away camp where I was a counselor. The campers were 13- and 14-year-old girls about to start their freshman year of high school. The campers could ask a group of counselors any questions about what high school was like, and we would try to assuage their fears as much as possible. The discussion turned to periods, and after sharing some horror stories about inopportune bleeding, the other counselors and I inevitably began telling the girls where we would hide our tampons—in sleeves, our shoes, pencil cases. But then, another counselor spoke up. “I don’t understand why everyone feels like they have to hide their tampons,” she said. “We should just be able to get one and go to the bathroom.”

In that moment I realized how complicit I was in society’s system of menstrual stigma and period shaming. As soon as a young person gets their period, they are trained to experience it covertly and discreetly. Even when talking to other people who menstruate, we speak in euphemisms and in hushed voices. We are trained to see the act of menstruation itself as disgusting, inappropriate, and shameful, even though it’s not something we have any control over. The more I thought about it, the more baffling it was: Why was I (and almost everyone I knew) afraid to be caught holding a tampon?

Periods, as well as sexual and reproductive healthcare, have been stigmatized for far too long. This comes with consequences. For decades, period stigma has barred menstruating people from proper healthcare, adequate economic support, and in some cases, even their education. We all must embrace the discomfort of breaking the silence until the shame disappears completely.

I have been trying to work on this myself. Since the publication of the article in my high school newspaper, people have come up to me to talk about their periods. Everyone seems to have their own menstruation horror story, especially when it comes to their first period. (Mine, for instance, was when I was twelve and at sleepaway camp for the first time—my mother will never forget that letter home!) Across my community, the country and even the world, it is wonderfully empowering to watch this new wave of menstrual activism take hold. I am grateful for the work Rebecca Stone and other local legislators and activists have done to pass the historic warrant in Brookline and other legislation across the country. Someday, tampons will be as common a healthcare product as toilet paper and paper towels—and that someday is looking sooner and sooner.

A Massachusetts native, Sarah Groustra currently attends Kenyon College in Ohio. She was a 2015–2016 Rising Voices Fellow at the Jewish Women’s Archive. A version of this piece appeared on jwa.org, and on the Lilith Blog.

- No Comments

April 11, 2019 by admin

Can Leviticus’ Purity Laws Help Us Understand #MeToo?

The poet Galit Hasan-Rokem wrote the following poem entitled “This Child Inside Me”:

This child inside me

Sorts my existence into elements:

Blood and urine

Calcium and iron.

In my sleep I am a quarry

Where rare treasures are suddenly found.

Blood and urine, calcium and iron. The fluid and elements that, in part, make up the physical constitution of a human body. This is, in part, the focus of our Torah portion earlier this month, called Parashat Tazria—which is always a confounding one for the bar or bat mitzvah student. The particular section of the Torah that we read at this time of year addresses issues of ritual purity. Some of those considerations include menstruation and childbirth. This part of the Torah is, indeed, a bar or bat mitzvah student’s worst nightmare. Every year, one or two innocent and unknowing soon-to-be 13 year old finds themselves forced to find relevant meaning in rules concerning nocturnal seminal emissions and afterbirth. Meanwhile their more fortunate classmates with simchas that land in the fall are assigned Noah’s ark and the Garden of Eden.

Leviticus builds character.

- No Comments

April 2, 2019 by admin

Are You a Woman Who Survived Concentration Camp? Or Her Daughter or Granddaughter?

We are eager to document the forced administration to women of substances that led to the cessation of their menstruation and, for some, infertility and miscarriages afterward.

In the years after the Shoah, the common and understandable medical assumption was that the cessation of menstruation in the camps was the result of malnutrition. But there is now data to refute this: both the emaciated women arriving to Auschwitz in 1944 from Poland’s ghettos and the women arriving in 1944 from Hungary, where they were not starved, all stopped menstruating immediately after arrival, regardless of differences in body mass.

Some women reportedly received injections, others were forced to ingest food or liquids which contained a similar substance. In both cases the women ceased menstruating—some for months, some for years; some suffered miscarriages or were left permanently infertile. Self-reports suggest that the younger the adolescent girl at the time she arrived in the concentration camps, the greater the long-term impact upon her future reproduction.

These interventions were conducted so routinely that this history has been unspoken and its connection to long-term effects unrecognized. Interviews with survivors indicate that they were part of the “processing” of those new female arrivals at Auschwitz (and perhaps other death camps) who were not killed immediately. Women survivors’ experience related to their subsequent fertility may also have received limited investigation because of the sensitive and taboo subject. Survivors themselves may have been reluctant to raise the issue, and earlier interviewers may not have thought to—or had the training to—ask questions that would elicit such material.

To uncover these missing stories, one of my colleagues and I are seeking to interview female concentration camp survivors and any children of survivors whose mothers may have shared with them stories about their post-Holocaust fertility challenges. While there is no cohesive, documented narrative of this particular experience, stories exist vividly in the memories of survivors who still do not know what exactly was done to them or why. We are attempting to assemble the fragments of this unknown chapter of the Shoah and to hear from women and their children. We can conduct interviews in Yiddish, English, Hebrew or French. Not only do these women’s stories deserve to be given voice, but also there may be important medical consequences for the second and third generation.

To be interviewed, contact Peggy J. Kleinplatz, Ph.D. at 613-563-0846 or Paul J. Weindling, Ph.D. at pjweindling@menbrookes.ac.uk.

- No Comments

April 2, 2019 by admin

Period. End of Sentence. •

The taboos against even mentioning the word menstruation are profound in rural India, among young and old, male and female alike. These taboos and the introduction of a cottage industry to manufacture and sell sanitary pads are the subject of an Academy Award winning Netflix short documentary created by Rayka Zehtabchi. Many other cultures can learn from the destigmatizing. netflix.com.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...