Tag : menstrual cup

November 5, 2019 by admin

Period Talk

There is now an Instagram hashtag for #periodsex. This openness is one example of a new wave of menstrual and hormone awareness and positivity emerging in the digital realm, with its fast-paced conversation, a tendency for sharing (or oversharing) and cultivation of a new generation of outspoken feminism.

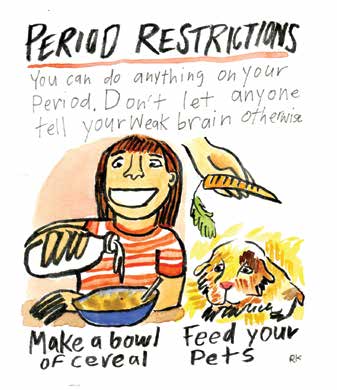

Comic by Rebecca Katz

Whereas a self-respecting feminist might once have bristled at the idea that mood swings affected her outer demeanor, women now tag their cranky selfies with #lutealphase or snap pictures of their PMS snacks, discussing without shame everything from hormonal birth control to the value of diva cups. Pregnant people and trans people talk about the effect of shifting hormones, while some Jewish women are exploring new and interesting approaches to the mikveh, the ritual bath.

When you scan these social media posts, you net the usual suspects: memes about how it’s gross, stories from men who, to their horror, had mistaken blood for what they thought was arousal fluid, and an assortment of images ranging from stunning to disturbing. Sex during one’s period remains predictably stigmatized—but not utterly. That same hashtag calls up articles on why period sex can be great: orgasms relieve cramps; it allows for an intimacy you might not have previously had with your partner. Plus (if you’re into that kind of thing), having sex during your period could be an opportunity to confront some of your own shame and stigma around it.

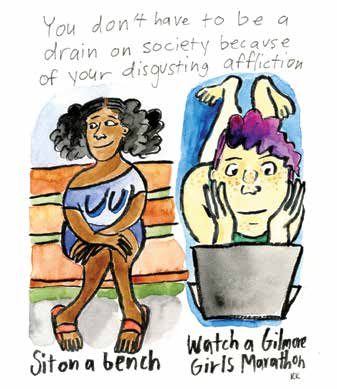

Comic by Rebecca Katz

TRADITIONAL RITUALS AROUND MENSTRUATION

A discussion about “period lifestyle” (a phrase borrowed from a 2019 Cosmopolitan.com piece about period trackers) wouldn’t be complete without revisting the concept of mikveh. Mikveh, or the ritual immersion undertaken monthly by observant Jewish women to restore “ritual purity” after menstruation, can be a contentious subject. Should feminists entirely reject the notion that one’s period renders you impure? Traditional Jewish law prohibits sex or touching when one partner is menstruating, so sex during one’s period is taboo. But the subject of menstruation comes up a great deal in studying Jewish laws and practices around periods.

Is there a way to see mikveh as celebrating the body, as selfcare, as time reclaimed for oneself ? This quandary remains intact after decades of argument, and while it’s far from resolved, the discussion does promote confrontation with taboo, and the consequences of enacting religious law on physical bodies. In fact, some people think that the “reclaiming” of the mikveh has become a victim of its own success, used now to mark a shift of any sort, whether a celebratory move from one state to another (a graduation, a marriage, even a divorce) and also a gender transition, without regard to mikveh’s original purposes. Here’s writer Tara Mendola on the Lilith blog: “Without a nod to that link between blood, water, and the Covenant that first wrote mikveh into the medieval Jewish imagination, liberal Judaism and the progressive mikveh movement miss an opportunity for sex-positive, body-affirming discussion of what it means to be a person who can get pregnant.”

An observant married Jewish woman would typically immerse in the mikvah every month, seven days after the end of her period, in order to render herself once again ready for sex with her husband (sex with a menstruating woman is forbidden in Jewish law, and she is referred to as niddah until the mikvah immersion). Mikvah is no longer the domain solely of religious, married Jewish women, however. Mayim Chayim is a mikvah and learning center in Newton, Massachusetts, where people of all genders can perform the mikvah ritual for purposes of conversion, marriage, healing from trauma, miscarriage, divorce, illness and other transformative experiences. A similar “progressive” mikveh experience in Manhattan is facilitated by ImmerseNYC.org

“I see more and more people who menstruate who are not Orthodox or becoming Orthodox and who are feminist getting involved with mikvah,” says Rabbi Sarah Mulhern of the Shalom Hartman Institute. “They are saying, Hey, Judaism has what to say about how I eat and structure my time and all the other basics of my life, why shouldn’t it have something to say about my sex life? About my experience of menstruating?” Mulhern says she’s surprised by the number of requests she gets to teach classes on mikvah and the laws of ritual purity, including from queer and trans folks, which she attributes to “an embrace of halacha outside of normative Orthodoxy more broadly, as well as a broader increase in comfort with and talking about menstruation.”

When cisgender straight egalitarian couples attend Mulhern’s classes on mikveh, men listen to their female partners talking openly about menstruation, and take part in a discussion about it, a phenomenon Mulhern says she assumes was not happening a generation ago. “This crowd,” she said, does not “pretend that much of the history of how these laws evolved did not happen in a context of misogyny and fear of menstruation. That’s real, and they know that. But there’s a sense that there’s still something in niddah that’s valuable. There’s less anger and more curiosity, which I think has to do with a sense that there is something deserving of sanctification in menstruation.”

TECHNOLOGY IN THE SERVICE OF HORMONAL AWARENESS

In addition to an interest in menstruation linked to religious observance, there are now apps which allow people who menstruate to track their periods from a hormonal perspective, so they’re aware through the month of PMS symptoms, ovulation, heightened fertility, and more. Accompanying this shift in perception and value is an entire industry of period equipment. Beyond pads and tampons, there are now reusable pads, menstrual cups, and period underwear like THINX (that’s underwear designed to absorb menstrual blood on its own, with no addition of pads or anything else).

MOVING PAST THE FEAR OF REVEAL

In October 2018, Aurora Tejeda wrote in Vice magazine about her experience of “free bleeding,” reflecting on how seeing musician Kiran Gandhi run the London Marathon while openly menstruating (without a tampon) changed her own perspective on her period. Tejeda documented what it was like to bleed without using any kind of menstrual product at all. While she worried about staining clothing and sheets, she ultimately found that her cramps were not as bad as usual, and she didn’t bleed onto things as much as she thought she would, even after taking a yoga class on her heaviest day. And if she did bleed through her clothes for all the world to see? “Honestly, who cares?” she wrote.

Free bleeding and period sex, as well as menstrual cups— and, to some degree, even period underwear—invite people who menstruate to confront their bodies directly in a more uninhibited manner. Letting blood flow from our bodies without attempting to confine or limit it allows us to be vulnerable, and menstrual cups necessitate that users get acquainted not only with anatomy, but also with the realities of leaking, spilling, and potentially cleaning up in public places. These options further emphasize that menstruation need not be hidden, and that menstruators need not live in perpetual fear of reveal.

While it’s still not totally unheard of to slip a tampon into your pocket or your sleeve on the way to the bathroom, people who menstruate are distancing themselves from the idea that getting and having a period is something to hide and deny, taking advantage of a new openness around menstruation to be more open about other issues of sexual and reproductive health that were once considered taboo.

“I do talk about my period. With everyone!,” says Sue, who’s in her 40s, and uses the Clue app to track her menstrual cycle. “I won’t go into gory details with someone who isn’t there for that, but I refuse to be silent about it either. I have three kids, ages 16, 20, and 29. The oldest and youngest identify as male and have always been brought up hearing women discuss their periods and are educated about what they’re like for people who bleed and thus they can be supportive. It comes up at the dinner table on the regular.” Sue has also created a zine—a self-published magazine—entitled Bleeder, about her period, as well as about intersectional feminism, her identity as a witch, and social justice.

WHAT ILLNESS DOES TO US

We might well be in a sort of period renaissance, during which we’re hunkering down and getting to know what our hormones are doing, how it feels when we ovulate, and how much we really do or don’t need to micromanage our periods. But what about when our bodies make us feel powerless and frustrated? What about when our menstrual cycles aren’t predictable, when they’re much longer than 28 days, when we struggle to manage their unmanageable pain? How then might we feel about reclaiming menstruation?

A woman we’ll call P., 30, has endometriosis and adenomyosis. She needs to report symptoms like pain, period length and heaviness of flow to her doctor, and so she tracks her period. “As a result of these illnesses, I really, really hate my period,” she says. “When I was a teenager I felt ashamed of my period, but as I learned more about feminism, I tried to embrace it. I felt like the reason I was ashamed was because society taught me it was shameful. I learned to not be embarrassed, and I think I would have kept feeling more positive about it if my endometriosis/ adenomyosis symptoms hadn’t increased in severity.” After P. began having prolonged, extremely heavy periods in her late 30s, menstruation, which had once given her peace of mind (it meant she wasn’t pregnant and that she was healthy) became a source of anxiety and fear. “When I started getting the depo shots and my period stopped entirely, I didn’t miss it, because instead of being an indicator of all being well, it was a portentous sign of my demise. Not having a period became my wellbeing.”

THE ART OF THE PERIOD

And then there’s the art of the period, literally. Initially part of a movement for body pride in the 1970s and early 80s, at the height of the second wave of feminism, artistic reclamation of menstruation has had something of a renaissance now also. Artists like Casey Jenkins have been creating art using their menstrual blood. In 2013, Jenkins wove a scarf with yarn she inserted into her vagina every day for 28 days, through her entire menstrual cycle. Part of Rhine Bernadino’s “Working from 9-5” series involved her sitting on a white chair in front of a white table, eyes closed, completely still until she removed her menstrual cup and poured the contents into a jar on the table, without spilling a drop. Back in 2008, when Aliza Shvartz created performance art that involved allegedly self-inducing miscarriages, the media could not get enough of the “controversy,” but she has quietly been reclaimed as a pioneer of feminist performance art, whose work illuminated out some of the murky distinctions between abortion, miscarriage and menstruation.

Today, Google “period art” and you’ll find a litany of projects by artists throughout time creating work that not only calls attention to what it means to live in a menstruating body, but also its political and social implications. What if menstruating bodies were seen as powerful instead of requiring outside control? What if they were regarded as art instead of reviled and feared? And what if we allowed ourselves to truly embody that reality?

Chanel Dubofsky writes fiction and nonfiction in Brooklyn, NY.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...