Tag : Liana Finck

September 26, 2018 by admin

Liana Finck on Her Shadow

New Yorker cartoonist Liana Finck details the struggle for acceptance of a weird kid in Passing for Human: A Graphic Memoir (Random House, $28), her new book. Leora, as Finck names her fictional self, uses her shadow as the symbol of her otherness.

Having been a weird kid myself, I could understand feeling that you’re an alien, and desperately wanting to pass for human, like the other kids. (Although, in Finck’s page “Elementary School Hierarchy,” in which she describes the levels of cool kids and uncool kids, I related most to the kid, “who didn’t want to be cool. She liked science fiction.”)

Desperate to belong, Leora chases away her shadow so she can pass for human, and everything is hunky dory until, as she becomes a teenager and then an adult, she realizes she has forgotten how to draw. Finck quotes Andrew Solomon, who himself is quoting from Hans Christian Anderson’s “Little Mermaid”:

“Her wish was granted: She became a human. The price was that every step she took was like walking on knives.”

Without our shadows, we may pass for human, but we are walking on knives. It was Liana/Leora’s shadow that made her a New Yorker cartoonist. Of course! Everyone with an ounce of talent was a weird kid!

But wait! We find out that Leora’s mother also lost, and found again, her shadow. And that she too had chased away her shadow, but for an entirely different reason! When the mother’s shadow finally returns to her, it still wears the long braid that the mother had cut off when she sent the shadow away. So, does the shadow represent more than the weirdness that makes us create? Don’t expect me to answer that question, because I admit I actually have no idea what Finck is suggesting.

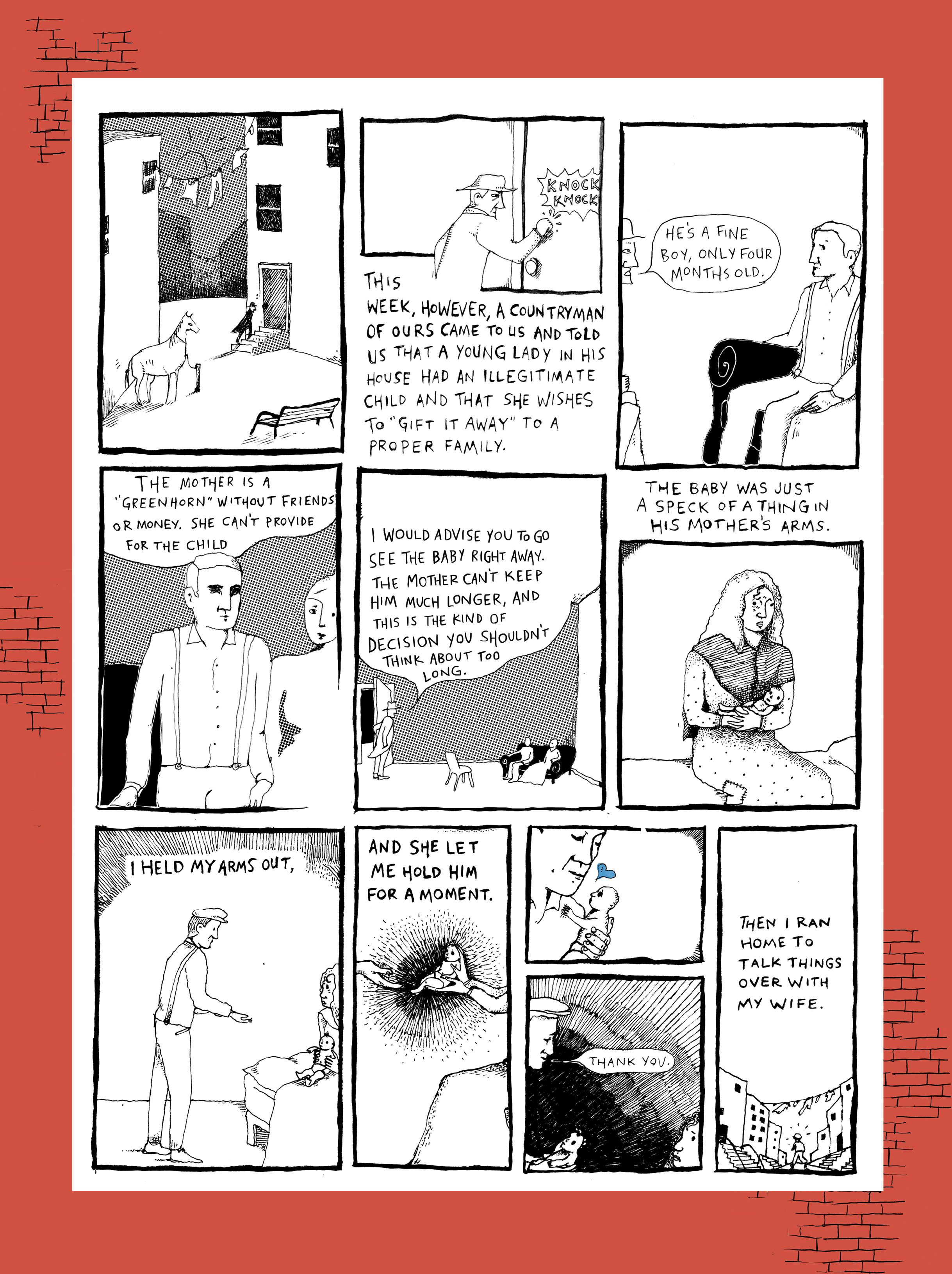

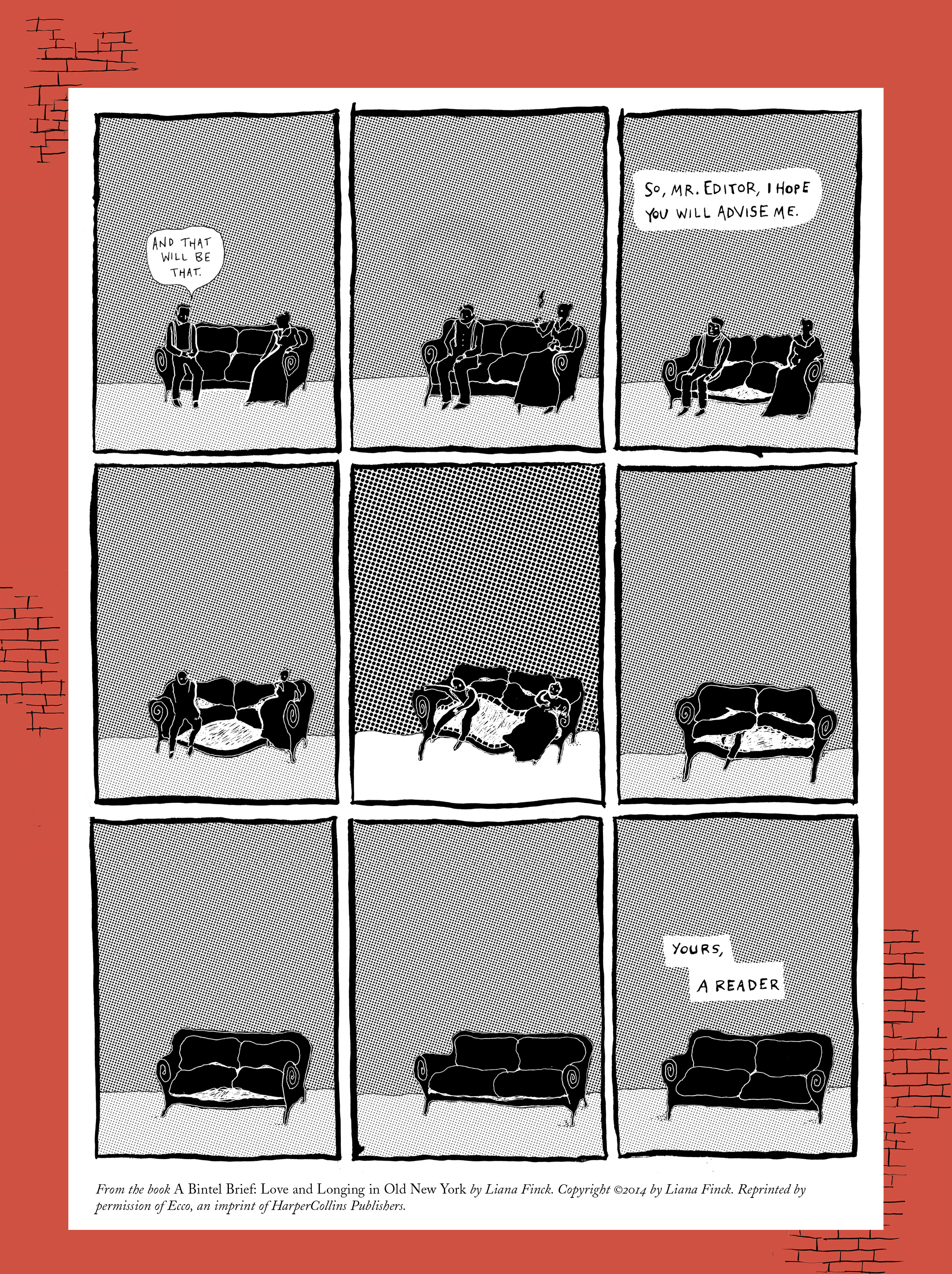

Some years back, I had eagerly picked up and thoroughly enjoyed her first graphic novel, A Bintel Brief, because I knew about and was interested in the fabled advice column that had run in the Daily Forward newspaper during the early 20th century. Perhaps inspired by A Bintel Brief, Finck now contributes a hilarious online advice column to the New Yorker, “Dear Pepper.” (Pepper is a dog.)

Passing for Human is a horse of a different color. Longer, more complicated, and harder to figure out, even drawn in a vaguer art style, at least one panel was so amorphous that although I could make out two arms, I absolutely could not find the head that went with them.

If you dip a spoon into the pudding that is Passing for Human, you may pull out some delicious plums: a charming retelling of the creation myth with a female God, and later another retelling with a sympathetic female devil. A retelling of the story of Job, starring Leora’s father as Job. Best of all, a last section of the book narrated by Leora’s shadow, in which the blacks and whites are reversed, like negatives.

Though I liked A Bintel Brief better, plums like these make Passing for Human worth the struggle. TRINA ROBBINS, artist and cartoonist, is author/editor of The Complete Wimmen’s Comix, Last Girl Standing, and A Minyen Yidn.

- No Comments

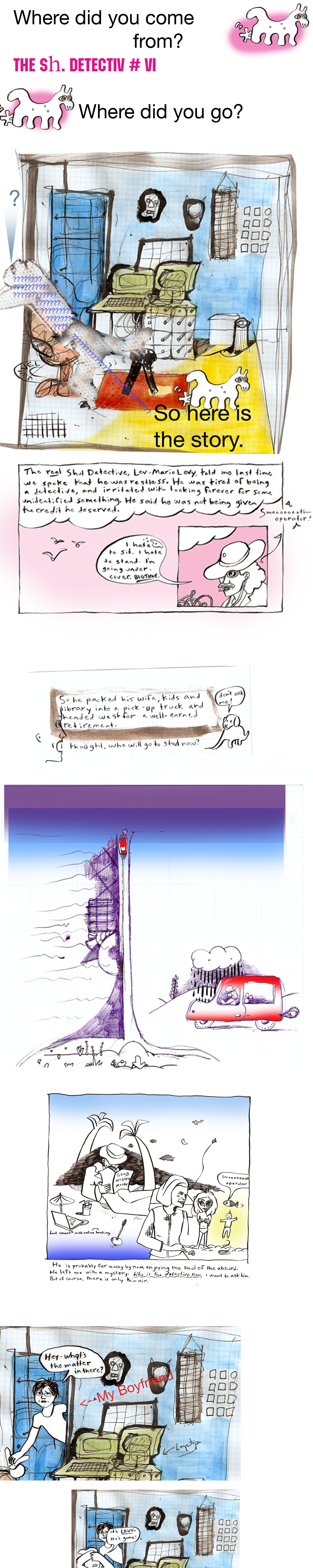

January 21, 2015 by admin

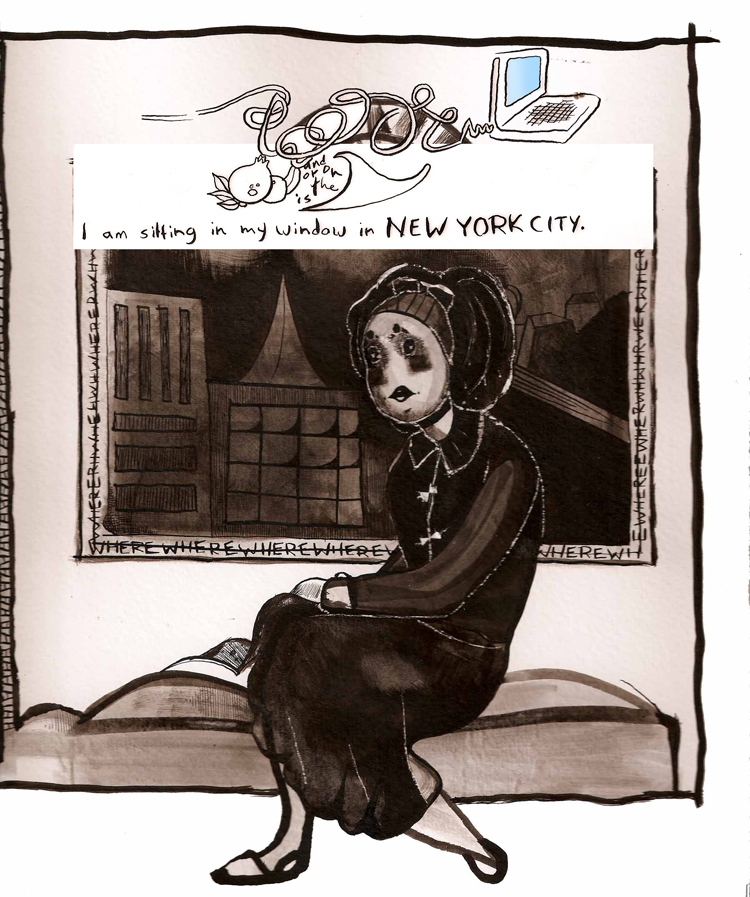

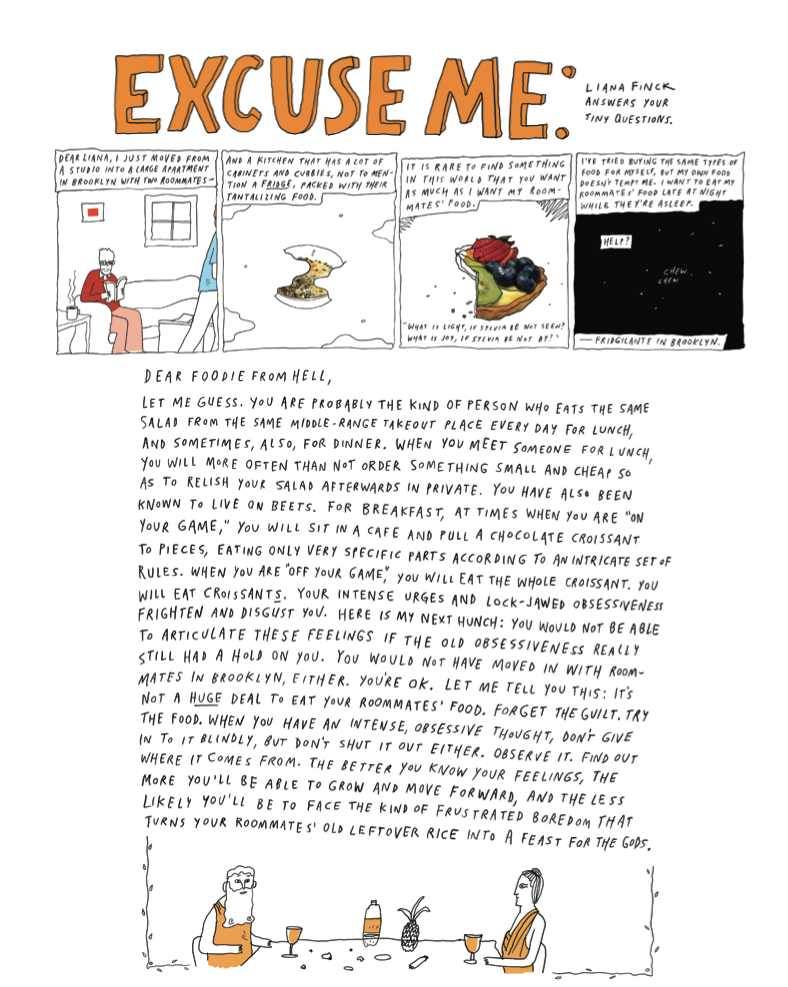

Excuse Me: Coveting Thy Neighbor’s Food

Liana Finck’s graphic novel is A Bintel Brief. She writes and draws a monthly column for The Forward and her cartoons appear irregularly in The New Yorker. Her graphic blog — “Excuse Me” — appears regularly at Lilith.org/blog.

Liana Finck’s graphic novel is A Bintel Brief. She writes and draws a monthly column for The Forward and her cartoons appear irregularly in The New Yorker. Her graphic blog — “Excuse Me” — appears regularly at Lilith.org/blog.

- No Comments

July 15, 2014 by admin

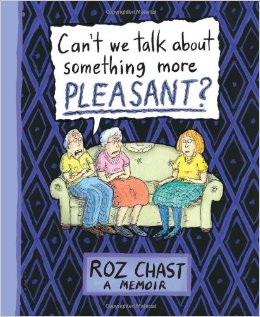

Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?

Roz Chast’s new memoir.

Calling Roz Chast’s new book a tearjerker would be silly.

The graphic memoir will evoke noises from you that a normal crying person would not make: low moans, ragged breathing.

It took me a second to realize that the Sounds of Grief were coming out of me—I was the person enjoying this fantastically quick-witted, sweet, insanely and perceptively funny new book by her favorite cartoonist. But they were.

Roz Chast’s cartoons have been an (the?) off-the-wall mainstay of The New Yorker for decades. They feature nervously drawn, quavering people, stupidly smiling horses, and inanimate objects with delightful expressions on their faces. They are often set in living rooms and sometimes include a lumpy couch, an armchair, wallpaper, and a really stupid painting of boats on the wall.

On the cover of this book, the author sits with her two aged parents on a lumpy couch that is familiar to us from her cartoons. The argyle-patterned wallpaper is of a deathly hue: dark purple on black. All three of them look deeply uncomfortable.

The title, “Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?” is what Chast’s parents would say to her whenever she tried to talk to them about “end of life plans.”

George and Elizabeth Chast were born in 1912, 10 days apart. They grew up two blocks from each other in East Harlem, and were in the same fifth grade class. Elizabeth had been an assistant principal, domineering and “built like a peasant,” who referred to her terrible temper, chillariously, as “a blast from Chast.” George was a high school teacher. He was slight, kind, an explorer of word origins, a careful chewer of food, and suspiciously inept when it came to using toasters and other gadgets.

He loved bananas; she hated bananas. They argued often about fruit and other things. But they referred to each other—this was both sweet and a little horrifying—as soul mates. They did everything together.

In one of the first pages in the book we read the story of how, one day in 1940, a light bulb burned out in their apartment. George had a phobia of light bulbs and also of step stools, so Elizabeth stood on the stool and replaced the bulb. She was six and a half months pregnant. Soon after that, the pregnancy developed terrible complications, and she gave birth, prematurely, to a “perfectly formed, but blue” baby who died one day after it was born. The complications had nothing to do with the changing of the light bulb, but still the connection between baby death and changing light bulbs became an unspoken part of family lore. The story does not come up again, but it sets the tone of the book, which is a tragedy told in anecdotes.

Baby Roz came along 14 years after that first baby. An only child, she always felt like an intruder in her parents’ “tight little unit.” In the family photographs included in this book, she is not smiling.

In 2001, after avoiding Brooklyn for 10 years, she has a sudden, intense urge to visit her parents, who are nearing 90, in their old home.

The first thing she notices is that everything in the apartment is coated in grime. Her parents are frailer than she thought, and less able to manage. Uneasily, she wonders: what next.

Two days later, the twin towers fall.

Her parents quickly go back to arguing about bananas. But their decline is underway.

In a series of keen, lucid observations of tiny, insane details, Chast describes her father’s senile dementia and her mother’s harrowing digestive ailments, the weirdly cheerful “Place” she convinces them to go live in (she hangs decorative corn cobs on their door, because “when in Rome”), their fear and crankiness, the responsibilities that land on her, the chilling truths about “stuff ” known only to people who have had to clean out their parents’ houses. This is the story of George and Elizabeth’s drawn-out, confusing, stressful, sad, expensive deaths.

The narrative is modular. Each page could easily stand on its own as a full-page cartoon —the type Chast publishes, when we are lucky, in The New Yorker. Each page, on its own, is completely funny— funnier than sad.

How does Chast string together the “minutiae” of cartoons and anecdotes and old photographs? Did she put a lot of work into switching from “cartoonist”’ to “graphic novelist”? Did she change her voice to accommodate the seriousness of the subject matter?

If she did wrench this story out of herself—if she did strain herself to make a million tiny and difficult adjustments to her craft—we can’t tell. The story flows so easily. The large-scale tragedy grows out of the surprising and human details as naturally as it does in Shakespeare. When you read Romeo and Juliet, you don’t say: wow, how does he focus simultaneously on the big and the small, the sad and the funny? Somehow, deceptively, while you are reading, everything is obvious to you: the story could not have been told any other way, and it is the only story that could have been told. Roz Chast makes telling the sad truth in funny pictures seem effortless—makes it seem obvious.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...