Tag : Jewish hair

October 7, 2020 by Rebecca Sassouni

I Had Planned a Midlife Hair Makeover— Then Covid Showed Up

Dear Reader,

In the midst of a terrible season, allow me some self-indulgence.

During the winter of 2020 before the world derailed with Covid-19, I was 49 years old, facing my 50th birthday with a mix of excitement and resignation. Certainly, I was glad to be healthy, in an intact marriage, with growing wonderful children, and a full roster of friends, family, social engagements, community service, and even a resuscitated second act after retirement to practicing as an attorney in solo practice.

- 1 Comment

July 27, 2020 by admin

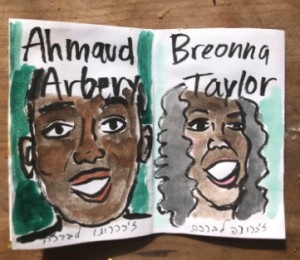

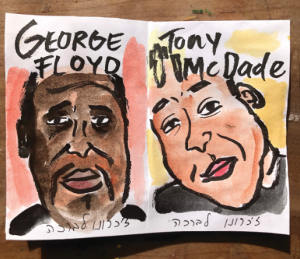

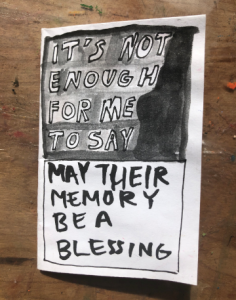

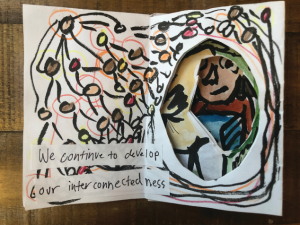

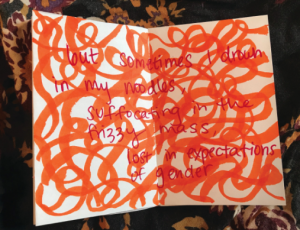

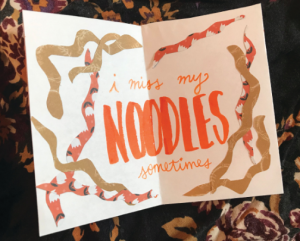

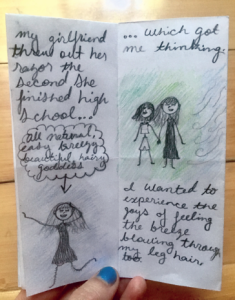

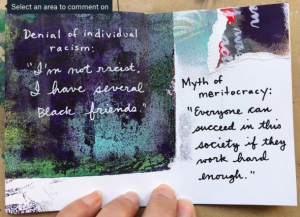

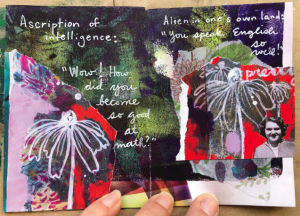

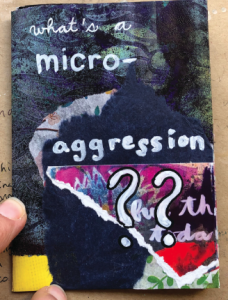

Quaranzines

“Recall your worst haircut!” and “What’s the world calling you to do right now?” Art and writing prompts like these drew avid participants to Lilith’s recent Zoom-based zine-making events inspired by our pandemic-induced desire for a Jewish feminist space to combat isolation and alienation. ’Zines—highly personal and handmade—have a history as a kind of feminist samizdat, self-published and presenting themes that can elude mainstream storytelling. Sample the results here.

Sign up at Lilith.org for Lilith’s free online newsletter to find out more.

- No Comments

April 20, 2020 by admin

Head Covering: The Evolving Choices

My mother’s hair is colorful ropes of cotton, carefully and methodically wrapped in a rainbow of layers growing in width as the ends disappear into hidden corners below her hairline. As a girl, I often sat in my mother’s room, watching her in this morning ritual as she added the last detail of her dressing. Her movements fluid as she built her crown of fabric, adjusted the turban around her head for better comfort, and the way she took care to tuck in any stray hairs that had escaped the careful head wrapping. My mother’s hair made rare debuts. It was very short and very black, uncovered only in the mornings while she sipped her coffee. I fantasized about my mother’s hair, wondering what it would be like to witness her in the long wavy locks I had seen in the photographs of her before she was married, before she began covering. I longed to witness this femininity in my mother, to project into reality my own ideas of what a woman’s hair should be. But my mother’s hair was only ever a diadem of rich colored cloth.

Lots of things embarrassed me about my mother during adolescence, but for some reason, her turbans never did. Not in the secular public nor in our Orthodox Jewish community, where most married women wore synthetic wigs or snoods. It never embarrassed me because it came so naturally to her, was so much a part of who she was. These turbans she donned regally, her closet full of scarves hanging on hooks or folded in her armoire. I never questioned her choice to cover her hair this way, to stand out wherever she was. I also never questioned that I too would one day cover my own hair when I married. When I was young, it seemed inevitable, without question; I would cover. I hadn’t even liked my hair anyway.

I have boring hair. Brown. Limp. Easily tangled. At 14, I cut it all off. I’d had enough of my hair. My hair drew looks of daggers from the rabbi of my ultra-Orthodox high school. I was the only one with hair that short, a pixie cut—an utterly rebellious move, to stand out so blatantly. But then I missed that long, ugly disappointment of hair. By the time I was graduating, my hair was long again. I remember the small held breaths as my friend and I took turns laying down our heads on a towel, spreading out each other’s hair, and then, with a hot clothing iron, straightening each other’s hair stick-straight style. We risked burns at each other’s hands in order to obtain what we thought was a sleek, sexy look.

And then, only two years later, at the age of 19, I met my husband and we fell fast and heavily in love. I was engaged at 20 with a wedding on the horizon. And that is when the rainbow coverings fell out of grace. On my mother, the covering of her hair felt all-encompassing of her identity. I understood it not only as a religious observance but part of her artist’s dress. But when suddenly faced with the covering of my own hair, I panicked. It had only been a few years since I finally understood my hair, and when faced with the prospect of hiding it from the world I realized I wasn’t ready.

I have been married 14 years, and my relationship with covering my hair is still complicated. At first I covered with hats only on Shabbat. Then my sister passed on to me a human-hair wig which I wore on Shabbats and the holidays. I tried taking on covering my hair on Mondays, but it was too difficult and I gave it up, followed a short while later by taking on covering my hair on Fridays, an easy transition into my Shabbat covering practice, which I still do today. I own two human hair-wigs, one long and one short, to go with whatever hair length I might be sporting that year. On Fridays, I cover my hair like my mother. And I think of her each time I wrap my hair. I wrap it differently , a more modern look with a twisted knot at the top of my hairline. But my face morphs into hers. And it makes me miss being young again, watching her wrap her hair. An art form; my Jewish mother.

I don’t know if my daughters will choose to cover their hair when they are married. I don’t know if they are entranced with the ways I cover my own hair, or style it when it is uncovered. But they do rely on me now to care of their hair. The feel of their scalp beneath slippery suds as I bathe the younger ones. The row of girls before me as I brush and brush their hair—hair so spectacularly different from my own, shades of blonde and strawberry, all of them with body and curls—hair so thick I sometimes find myself enviously running my fingers through it. Such a palpable part of their personalities, the hair that grows from their heads in such symbolic manifestation of their unique selves. These daily rituals of washing and brushing, it’s hard to imagine one day all these locks might be locked away.

Talya Jankovits holds her MFA in creative writing from Antioch University and is a Pushcart Prize nominee.

- No Comments

April 20, 2020 by admin

Waxing Nostalgic

In 2014, my friend Tess and I went to see a comedy called “The Other Woman,” starring Leslie Mann and Cameron Diaz. Its jokes were dumb and obvious, and although the film was written by a woman and purported to be about the power of female friendship, it was insultingly sexist. Its biggest selling point was its apolitical mindlessness; it had no original ideas, and we didn’t want to see anything that might have made us think.

As a bookish, half-Jewish woman—the earnest daughter of a second-wave feminist—I rarely wear makeup and always wear glasses (not to look smart, but because I need them to see). I have worn the same pair of comfy Gap sales-rack jeans for the last four years. The fanciest outfit I wear on a regular basis is a black sweater dress over black leggings. Tess, though, is a glamorous platinum blonde with a multi-colored wardrobe—a real-life shiksa goddess.

We met in a graduate writing program. Most of our classmates were writing about big, sad, serious subjects: rape and murder and mental illness. Aside from a vague ambition to write, I didn’t know what I wanted. At the time, I was mostly writing long, boring, pointless essays about an ex-boyfriend. I was deeply anxious. Tess was sharp, confident, funny, and vibrant, a bracingly irreverent writer with an eye for indelible details.

There was a scene in the movie about waxing. The sad, aging, sexless wife played by Leslie Mann had to be tutored in proper feminine hygiene by the sexually sophisticated Cameron Diaz character. Afterward, I said something about how I could totally relate to the Leslie Mann character. I rarely waxed or shaved or did anything at all to my hair “down there.” I have paid for a bikini wax maybe twice in my life, both times before family trips to Florida.

Tess was stunned. Then she laughed. “Oh my god!” she squealed incredulously. “But you sleep with MEN!” I shrugged. “I’ve never had a complaint,” I said. It was true: I’ve always slept with men who don’t mind pubic hair or would find it too disgustingly patriarchal to tell me if they did. Feminists didn’t do that sort of thing, I thought. And besides, the handful of times I did wax, it felt weird: unnatural and uncomfortable, like I was extra-naked in an upsetting, exposed way, not a sexy, fun one. But I was embarrassed to realize what an out-of-touch weirdo I was. According to Tess, every woman our age (we were around 30 at the time) got bikini waxes.

For a week or so I worried that my OkCupid dates were secretly revolted by my unmodified body. Then I decided that I didn’t care. Maybe some guys were grossed out, or at least surprised, but that didn’t have to be my problem. Who had the money for such nonsense? Who wanted to walk around with an itchy vagina for weeks in between appointments? What was pro-woman about paying an immigrant lady $2 an hour to apply hot wax to your genitals?

Waxing never became a regular part of my life. But sometimes I remember Tess’s reaction to my innocent revelation and smile.

When I was younger I signaled my feminism by opting out of gendered conventions: I resisted shaving my legs (but ultimately caved); I tried not to obsess about my diet or weight. But now I can see that, oppressive grooming habits aside, there are ways in which Tess is the better feminist: where I am weak and afraid (of anything new, of minor changes to my routine, of traveling alone) Tess is bold and adaptable. Alone, she has visited countries where she knows no one and doesn’t speak the language. She has published one book and is working on the next. She knows how to get what she wants. What you do (or don’t do) to your body hair says something about you, but not everything.

Raina Lipsitz writes about politics and gender for The Nation, The Appeal, and Jewish Currents, among other publications.

- No Comments

April 20, 2020 by admin

My Mother’s Unshaved Legs

There’s an age at which you start noticing the things about your parents that are embarrassing. The fact that your dad will say something and your mom will then burst into song, triggered by a single spoken word; the noise he makes when he clears his throat; or the way she eats a piece of chicken with her fingers, down to the bone.

This is how it was with my mother’s unshaved legs. One day, I didn’t even notice the thin hairs, almost camouflaged by her freckles, and the next day I was mortified.

My mother—the primary breadwinner in the family—was not like my friends’ mothers. She did not attend school plays or drive carpools. My mother had been a teenager in the height of the Women’s Liberation Movement. She was in 11th grade when, inspired by the writings of Simone de Beauvoir and Betty Friedan, she stopped shaving her legs and armpits, and started to go without a bra.

By the time she was a student at Bryn Mawr, the bra was back on and the armpits were smooth once more, both for practical reasons. But the legs remained unshaven. It was just easier that way, and anyway no one really noticed.

Until I was 13. At 13, my friends had started shaving their legs and plucking their eyebrows, and my own body had taken a new shape, curvier and softer, more like my mother’s. A combination of the hormones, anxieties, and social tensions that are the hallmarks of the teenage years also conspired to cause in me a deep dislike of my own, ever-changing body, and thus the hatred I felt for myself manifested itself as embarrassment at my mother’s benign choices.

“I’ll never be like her,” I always told myself after slamming the door in the aftermath of a mother-daughter argument.

But when I was 18, I made a big decision to be just like her, and accepted admission to Bryn Mawr College. Bryn Mawr was a haven for individuality. With physical distance between my mother and me, I felt closer to her than I had during high school. I learned to accept her differences. She would never be the mother who attended school events, but she also never shied away from hard conversations—whether about sex, drugs, or leg hair—willing to answer my questions with love and care. She taught me that sex is natural and good, especially with someone you love; and that if I can’t have a conversation with my partner about sex, then I’m not mature enough to be having sex. She taught me that alcohol is more dangerous than marijuana, and that being grounded is better than being dead, so I should never get behind the wheel of a car if I’ve been consuming either. And she taught me that people will always judge me for my choices and my appearance, but if I’m confident in the choices I make, I can hold my head up high.

One day, in my early thirties, I looked in the mirror and for a brief moment, I could have sworn I saw my mother looking back. Randomly, I find myself erupting into song when a word triggers a familiar melody. After two children, my body has only continued to resemble my mother’s. Sometimes a full sentence will emerge from my lips and each word, each cadence, each facial expression, will mirror hers.

In my third trimester of pregnancy, I stopped shaving my legs. Not because I was motivated by Betty Friedan, but because I couldn’t reach them. And then I didn’t start again, because I liked the feel of it better, and it was just easier that way. At some point, I learned how to be my own person, not in relation to my mother, but with her guidance. Because my mom had taught me that it was okay to put my desires for my own body above what others thought was acceptable.

What I have learned from my mother’s unshaved legs is to be less judgmental of others, to live a life of my own making and, perhaps most importantly, to love myself.

Talia Liben Yarmush is an infertile Jewish mother, TV junkie, and Oxford comma enthusiast.

- No Comments

April 20, 2020 by admin

At the Beauty Parlor

I arrive on time for my 10 AM cut-and-color, but my new hairdresser isn’t there. It’s New Year’s Eve, I’m newly unwed and I want to party, but I look like hell.

“She’ll be here,” I’m assured by a redheaded stylist on a headphone call.

At 10:20 Barbie strolls in, blonde hair in a tortoiseshell clip, breasts contained in a low-cut red top under a calf-length black cashmere, with the perfect black patent leather slides I’ve been wanting. She is older than she looks.

In no hurry, she does her morning routine, arranging brushes and combs and checking her messages while I wait. By 10:50 I’m in the chair and she’s pulling at my curly hair, studying its creeping gray.

“What do you want?”

“My daughter to be alive, my husband to come home.”

Not hearing a word, she tugs the hair, examines the texture, then leisurely gathers the ingredients of a color recipe from the secret backroom where the chemicals reside.

I’m surprised I could state my wishes so clearly.

Another hairdresser arrives. Barbie compliments her shoes and starts painting my roots with a brush, revealing gray, making small talk.

“Ready for the New Year?”

“Hanukkah first.”

“You don’t have Jewish hair.”

“My ex does.”

“Uh huh.”

A man enters, cute, my age, takes a seat, opens People magazine with Prince on the cover. He can hear our conversation but salon rule is you talk out loud with the person cutting your hair as if no one else is listening.

Barbie heard from one of her clients that the divorce rate in Marin County is 75 percent. “There are so many good-looking women here, how can men help it?” She stands behind me, checks her looks in the mirror, adjusts her breasts.

“Would you take him back?”

I’m not sure that I would.

“I might.” Unless cute guy is interested.… I look for eye contact in the mirror (forgetting what I look like), but he’s engrossed in how Prince became The Artist Formerly Known as Prince by changing his name to an unpronounceable symbol representing all genders.

Next to me, New Year’s Eve plans: oysters, smoked salmon, crab, caviar.

Mmm, sounds good.

Two seats away, a twentysomething describes her new beau.

“You’ve seen him, the tall one.”

I get this feeling it’s HER, the mistress.

“Isn’t he a little old for you?”

“He’s 45… but he’s really immature.”

If I laugh out loud and no one hears me do I make a sound?

Barbie finishes styling a white-haired elder and starts “blonding” a crone with an oxygen tank. I get steamy, I will have to wait through another person, it’s past 11, I’m sitting here with my roots all wet, plastered to my head, the rest of my wild mane sticking up like a bush on fire, and my husband’s mistress is in the chair across from me looking fresh as her blonde trimmings drop from the scissors and gather like flower petals all over the floor….

Barbie comes by, moves a few hairs around, tells me I ought to call her to go out sometime. She has a lot of fun. She’s hitting 60, can you believe it?

“Of course, I had a great Brazilian facelift so I don’t look like I’ve been through a wind tunnel like some of the women in Marin,” she says and moves on.

The mistress is called by another name, I relax, it’s not HER. I focus on cute guy and note his wedding ring in the mirror. He’s going to his brother’s for

the New Year but can’t stand the brother’s “princess” wife. Why? She has opinions about everything. Barbie holds up the hand mirror and revolves the crone, who looks fabulous blonde, then escorts me to the back of the salon to shampoo me. My neck lowers into the bowl of the sink. Her long fingernails soothe my scalp and the warm water, perfect temperature, rinses. She is rinsing, rinsing; her long fingernails keep just missing the itch in my scalp.

“Everyone died last year,” I say.

“Uh huh,” Barbie says.

“My husband’s father, his mother, and our baby girl.” The truth of that makes me start sweating but the warm water just rinses it away.

“I remind him of death,” I say.

“Hence, the younger woman.”

A towel is draped around my shoulders and I cross the salon for the cut.

“How do you want the hair?”

“Smooth.”

She blow-dries my hair with a round brush, wrapping my naturally curly hair around the bristles until it’s completely straight.

“You look good now,” she says.

I don’t look like myself at all.

Marianne Rogoff is the author Love Is Blind in One Eye, the memoir Silvie’s Life, and travel stories, short fiction, essays, and book reviews.

- No Comments

April 20, 2020 by admin

Combing My Mother’s Hair

An erotic/sensual memory trip through crackles and changing colors of her hair. Heavy frizzy… foamy blonde… long wavy auburn… short Mamie Eisenhower bangs… little girl barrettes…. Still defiantly long and curling past her shoulders.

We tried to make her cut it as she reached a certain age (based on advice in women’s magazines). We forced her to go to the beauty salon with us, letting Mr. Paul raise his hands in horror: Erase that black! Too harsh! Too unnatural!

She emerged after six hours with a subtle sunlit auburn head of hair. Beautiful, youthful, but maybe too red, we thought. She looked in the mirror: it’s henna, she said. Just like henna. Within a week she bought her drugstore formula—jealously guarded through the years (one of us sent out to buy it so my father wouldn’t know) and voila! She tosses her black mane of hair at us, a gypsy flamenco dancer, a bullfighter.

The hair is thinning (but still thicker than ours). Such a dramatic color deserves dramatic clothes. My mother wears red, lime green, fire-orange. A hair breaks beneath the comb—still glossy black at the end, but pure white at the root. I look at the tiny bare spot on the scalp, almost imperceptible, and remember the sylph in tiny shorts and polka dot halter top of the 50’s.

Not too tight, she says, as I pull back her hair. Leave some curls on the sides.

Always coquette, always feminine.

I snap a beaded turquoise barrette around the ponytail and breathe in her hair. A wave from my childhood slaps me back. I smell the ocean in your hair: elusive salt and fresh sand smell, a grainy roar that fills eyes and nostrils. I smell the flesh of you too, always slightly damp it seems—fleshy and damp and pale—your Shalimar mixed with cooking smells: spices, cinnamon, vanilla—pungent herbs like cilantro and cumin.

I breathe you in and I’m on your lap again as we puzzle through the first American picture book I bring home from the school library. We tremble as we open the book to the first page. Flicka, Ricka and Dicka, pretty blonde triplets, smile back at us, beckon us into their safe black-bordered world where nothing evil can enter, no djnoun, no terrorists or Jew-haters, no rampaging mobs, no shrieking nightmare figures, no serpents with human heads. At least for now, we are safe.

In your hair too, I smell rage, my own impossible-to-control rage: at you, at life, at this world that made me who I am, a soft face hitting against a rock. I smell your own impotent fury at the teacher in Morocco who thrust your hair beneath ice water every morning to “get rid of those curls.” At the teacher who smacked your left hand with a ruler every day for a year until you managed somehow to write with your right hand—“but it was never natural, and now I write the way a chicken scratches in the dirt, going in every direction at once.” At your father who wouldn’t let the handsome boy (with heavy-lidded eyes and a curled lip like Elvis) court you because he was poor, and who took you out of school to marry Dad. At your mother who took two hour “beauty naps” every day while she left you with the younger brood of brothers and sisters to feed and bathe. They still consider you their mother.

Insular, self-educated, fearful and untrusting of strangers, c’est toi. I’ll go home later and find a note from you, scrawled in the same illegible hand, lines and words crowding, sliding off the page. Thoughts begun, never finished. You write me notes, phone me, leave me messages: was there ever anyone as alone as you? When you call me and leave a message on my answering machine, you never believe I’m not home: “Ruth. Ruth. Are you there, Ruthie? Ruth! Ruthie, it’s me, your mother. Are you there, Ruthie?” Until the message runs out.

I kiss the top of your head. Each strand evokes another memory, leads me down another path, as if your hair is a sea of unfathomable depths. Every time I dive, I discover clues that lead back to you, and I wonder where I begin and you leave off. Or perhaps that’s not even the question. Maybe all that matters is that I can breathe in your hair and remember—and here is what I wanted to tell you. Once, when I went to a writer’s colony for a month, my daughter wrote me a letter in which she told me that she slept with my hair ribbon tied around her wrist “because it smells of you, Mom.”

Ruth Knafo Setton is the author of the novel, The Road to Fez (Counterpoint Press) and the recipient of many awards. She has sailed around the world three times.

- No Comments

April 20, 2020 by admin

Hair-Pulling

Before my hair was patchy and thinned out from years of trichotillomania, the body-focused repetitive behavior of hair-pulling, I took unabashed pride in the fact that I was blessed with “good” hair. As a young girl I was acutely aware that my intelligence and confidence both came at a price. I was “gifted” and “an old soul,” but I was also a “know it all,” a “bitch,” a girl whose fourth-grade teacher urged her mother to “reel in.” My enviable brunette tresses— abundant, smooth in texture—produced a guilt-free external validation I didn’t otherwise experience as a high-achieving, precocious little girl.

As a teen at Jewish summer camp, I won the yearbook superlative for “Best Hair” long after the pulling began but some time before it affected my hair’s outward appearance. I didn’t have stereotypical “Jewish” hair, the kind imagined as frizzy or rough. When I reflect on the joy I took in this “natural blessing,” I’m ashamed of my participation in a tradition of white supremacist beauty standards. I’m ashamed of my own internalized anti-Semitism—Adrienne Rich’s “Split at the Root” provides much punny insight, here—and I’m ashamed of my complicity in racism against people of color who fight, still today, for the acceptance and celebration of their beautiful, natural hair.

In college, where childhood slowly ends, my feminist education coincided with the rapid disappearance of my hair. Much has been written on loss and childhood: the loss of innocence; of shamelessness; of the imagination; of naïveté. But the steady progression of my hair pulling into young adulthood produced a strange, different kind of loss. It was not simply a loss of hair but also of my ability to trust those around me wholly. My connectivity slowly severed, torn asunder like hairs ripped from the body. As I tried to grow into myself, I mourned the interrupted growth of my signature hair and found its absence created a distance between me and other people. I became hyper-vigilant at the slightest glance away from my eyes and up towards my hairline. Can they see? Do they know?

One night during my freshman year, I sat cross-legged in a circle with fifty other young women in the candlelit basement of our sorority house. The carpet cold and rough, we were expected to divulge our innermost struggles and traumas to expedite the bonding process, whereby strangers become fast, comfortable friends through shared emotional experience. This sort of bonding activity was familiar to me, as I’d grown up at a Jewish sleep-away camp better known for its commitment to friendship than sports. Even still, I was nervous and probably ripped a few hairs from my head as my heart rate increased and the sharing began.

Across the circle early on in the night, a then-future friend confidently announced that she had trichotillomania, a hair-pulling disorder, which manifested in pulling hair from her eyebrows and eyelashes. She even described, in detail, the therapies and medications she had tried over the years to help cope with the pulling. Mortified and awestruck by her ability to speak with such poise about a struggle I shared secretly, I said nothing to her that night or thereafter. Instead I cried in silent solidarity, weeping not for a bygone, “beautiful” version of myself but for the me I wanted to be then and still want to be now. Not necessarily the me who never pulls her hair, or the me who can share her feelings out loud without choking up. The me I wept for is the one who is working, still, on letting people in, on being gentle with herself and on whittling away at the stigma she assumes from the world and carries each day.

Jamie Zabinsky is an incoming English Ph.D. candidate at the CUNY Graduate Center in New York City, where she writes about feminism, activism and culture.

- No Comments

April 20, 2020 by admin

The Weight of Shiva

Sitting shiva for my father was hard. Our house was filled with people from morning until night, and I was sad. I wore the same clothing every day, with the rip across the front of that damn white button down shirt. We followed the ritual guidelines pretty strictly: the mirrors were covered up; we stayed inside the entire week; we didn’t take baths or showers. For our own sakes and the sake of our guests, we took sponge baths in the washroom sink.

We didn’t wash our hair for a week.

I was 13 years old.

To be honest, I don’t remember much about that week. I know I spent a lot of time in my room, and my wise, wise mother let me escape absolutely as much as I needed to. My friends came. They were nervous; this was the first time most of us had been touched by out-of-order, out-of-time death and tragedy. They stayed nervous, but we also laughed. We hung out. It helped, a lot. I remember (to this day) every one of my friends who came. And who didn’t.

I remember my hair getting greasier by the day. I remember my mother telling me to sprinkle it with baby powder. I tried wetting it, and pulling it back in a ponytail, and even resorting to a French braid. It weighed about a million pounds and kept getting heavier. I was aware of it in every moment.

I’m sure it looked fine. But how I hated how it felt. From that moment, I despised the feeling of greasy hair. Most of my friends would go an extra day or two between washes, hoping to preserve a good blowout or a new haircut. I never ever did. Never. The second I felt even a hint of grease, I headed straight for the shower.

In practice, I saved a lot of time. I never really even blow-dried my (long, wavy, brown) hair. It wasn’t worth it,because I’d be washing it the next day anyway. And the next day after that. And I’d leave the shower with wet hair, brush it and go. That’s always been my styling routine: clean. Product-free. Nothing that would weigh it down or add to the grease. I can always toss my head like a hair commercial, or J-Lo prepping for a half-time show. My hair is always ready.

Except that I recently went for my yearly hair appointment and the stylist told me I washed my hair way too often. I was drying out my hair, dragging down my curls and exhausting my scalp.

I’m all about making my life easier, and minimalist routines, and saving money, but I knew—just knew—that by day three at the most my hair would be a gross, heavy, oily mess.

But Diane-the-stylist is a wise woman. And having even shinier, softer, bouncier hair seemed very appealing. I decided to try it. And honestly, I spent a huge amount of time thinking about it. Huge. So I did it. And sure enough, by Day 3 I was topknotting with the best of them and Day 4 saw the headband come out. I gave up by Day 5. But week by week I could go a little longer, and my hair would look a little better. And I would feel a little better.

The only time I’d gone more than two days without washing my hair was during week long camping trips, when we went swimming every day and I wore a hat the rest of the time. And even then I longed for just one quick hair wash. But I wanted to give this a shot. And maybe—though I didn’t realize it then—I wanted to release my unwashed hair from the shiva memories, which perhaps weighed even more heavily than the grease.

Sharrona Pearl is Associate Professor of Medical Ethics at Drexel University.

- No Comments

April 20, 2020 by admin

Jewish Hair Now.

Twenty-five years after Lilith’s original, classic, sold-out hair issue, new writers untangle the knots that connect us to our mothers, our bodies, our backgrounds and our politics.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...