Tag : jewish food

July 27, 2020 by admin

The Ashkenazi Table •

Explore the heart of Ashkenazi Jewish food in a course featuring hundreds of never-before-seen archival objects, lectures by scholars, and video demonstrations of favorite Jewish recipes by renowned chefs. The essence of these Jewish foods has remained constant even as the recipes have evolved and changed with the migration of Jews around the world. Featuring Joan Nathan, Michael Twitty, Alice Feiring, Mitchell Davis (James Beard Foundation), Niki Russ Federman & Josh Russ Tupper (Russ & Daughters), Jake Dell (Katz’s Deli), Darra Goldstein, Liz Alpern & Jeffrey Yoskowitz (The Gefilteria), Lior Lev Sercarz (La Boite), Adeena Sussman, Ilan Stavans, Leah Koenig, Michael Wex—and more. Free if you register before December 31. Take the class at any time, at your own pace. yivo.org/Food

- No Comments

January 16, 2020 by admin

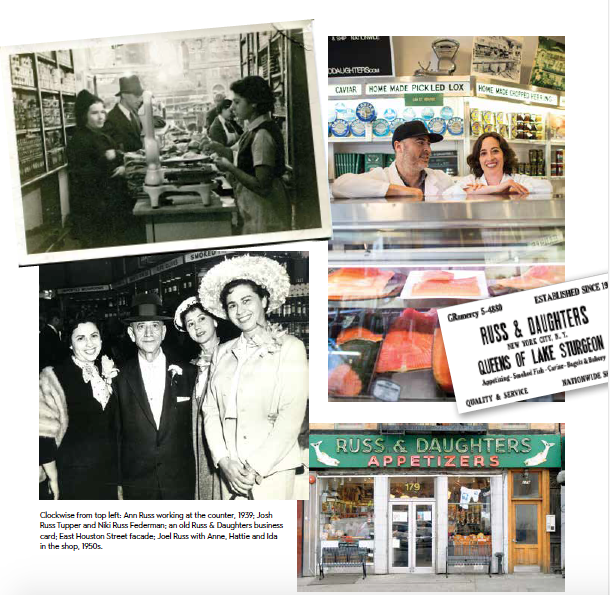

A Legacy of Lox

“You have to take a number!” a waiting customer instructed, pointing to a ticket dispenser that stood on the counter of Russ & Daughters, considered by many the holy grail of bagels and lox. Not realizing that the young woman she was speaking to was the 4th generation owner of the iconic appetizing shop, the customer raised a skeptical eyebrow.

“You have to take a number!” a waiting customer instructed, pointing to a ticket dispenser that stood on the counter of Russ & Daughters, considered by many the holy grail of bagels and lox. Not realizing that the young woman she was speaking to was the 4th generation owner of the iconic appetizing shop, the customer raised a skeptical eyebrow.

“Thanks,” Niki Russ Federman, 42, said with a warm smile. “It’s a learning process for everyone.” A crowd of eager regulars, food tourists, and neighborhood hipsters lined up and waited their turn, tickets in hand.

“It’s part of the ritual,” explained Niki, my friend since 2012. She wove her way through the store’s Lower East Side location which is as gleaming and thin as a perfectly sliced piece of lox. “The customers learn how to wait and the counter people give them their full attention.” That ritual—as much of a Jewish experience for some as any religious service—begins when the customer’s number is called, and an expert slicer handcrafts the order.

It’s a scene different from when Russ & Daughters began in 1914. That’s when a Jewish Eastern European immigrant named Joel Russ—Niki’s great-grandfather—fled from Galicia, Poland, to New York and began selling schmaltz herring from a barrel to support his family. In 1935 he distinguished his shop from the competition by including his three daughters—Ida, Hattie, and Anne—in the name and ownership of his business. All the daughters had worked at the store since their early teens, and unlike many daughters of the era, their hard work became a distinguishing feature of the family business. It might have been an unintentional feminist gesture, but it was groundbreaking nonetheless, and possibly the first business in America to include daughters in the name. It did not go unnoticed.

Remembering her childhood visits to the store in Julie Cohen’s documentary The Sturgeon Queens, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg recalled: “Even before I heard the word feminist, it made me happy to see that this was an enterprise where the daughters counted just like sons.”

Russ & Daughters is one of the few remaining “appetizing” shops in New York City. As opposed to the more commonly known delicatessens, or “delis” where kosher customers got flayshis foods like pastrami, appetizing shops were where Jewish patrons got their milchig foods, like herring and lox. As Jews assimilated, became less kosher, and moved out of the immigrant ghetto of the Lower East Side, the separate shops that specialized in “dairy” foods began to close. Russ & Daughters persevered, and began bringing production of these specialties in house so that everything they sold could meet their standards.

In 2020 it will be over a decade since Russ Federman and her first cousin, Josh Russ Tupper, took over the family enterprise. In that time they have opened two restaurants in Manhattan (including a cafe that regularly lands on the best-restaurant lists in New York City, and a kosher outpost at the Jewish Museum on 5th Avenue) and an emporium in Brooklyn’s Navy Yard complete with an in-house bakery. What was a staff of about 20 has grown to 160 under their leadership. They’ve retained the authenticity of food memories of Jewish New York’s Lower East Side while evolving into a foodie destination.

“What’s more New York than Russ & Daughters?” asked Peter Meehan, the food editor of the Los Angeles Times. “It truly is the apex of a certain kind of restaurant that was once more common in New York. Russ & Daughters is a conduit of a tradition.”

Anne, Niki and Josh’s grandmother, who once had ambitions to own a dress shop, subsumed her own desires and joined the family business instead. She would later recall that her social life as a teenager suffered because she always smelled of fish. Despite that drawback, it didn’t prevent a customer from setting her up with her future husband, Herbert Federman, who was described to her by their matchmaker as the “sheik of Brooklyn.” After their marriage, Herbert joined Anne and her sisters behind the counter at Russ & Daughters, marking the second generation of family ownership.

Their son, Niki’s dad, Mark Russ Federman, left his legal career and took the shop over from Anne and Herbert. With the help of his wife Maria (a scientist from Colombia, giving Niki Latina heritage and an ability to speak fluent Spanish) Mark ran the store for over 30 years, a time he chronicles in his memoir, Russ & Daughters, Reflections and Recipes From the House that Herring Built. “There’s a history of strong women in our family, and I think Niki is holding that torch,” said her cousin, and coowner, Josh. “People gathered around our grandmother, Anne, as the matriarch. We come from a long line of powerful women of which Niki is one.”

Russ Federman grew up as a shop kid, sneaking treats from the candy counter and watching older men hang out chewing on bokser, a carob pod commonly enjoyed on Tu B’shvat (it now lives on in the Café as an ingredient in egg creams). The store and its customers were absorbed into Niki’s consciousness from childhood, especially watching her father kibbitz with his opening question for new customers: “What’s your story, boychik?” It’s something Niki finds herself asking a new generation of customers from across the counter when she slices lox—only now it’s in Brooklyn, where she lives with her husband and two young children.

“Niki is invested in what Russ & Daughters is and what it means to the Jewish community for sure, but also to New Yorkers who have adopted it as part of their lives,” observed Meehan. “I love to see her in her white coat running things—and while I’m sure she could have chosen a different path for herself, I think any legacy she has been entrusted with is not something to uphold as much as something to keep vital and living, which I feel like she’s done an exceptional job of.”

“I don’t know if there will be a fifth generation that will want to continue on in the family business, but we make sure to care for it in the fourth so that if they do, it will be something they can be proud of, ” said Niki. In a world where so much food culture can be built on a “brand,” she tries to keep Russ & Daughters serving a combination of food and love.

For some American Jews, bagels, lox, and babka—among other Ashkenazi foods—are as much of a unifying force for Jewish community as any religious enterprise. Shared meals, from Sunday brunches to Yom Kippur break-fasts, are cultural events. But you don’t have to be kosher, religious, or even Jewish to enjoy the comforting qualities of matzah ball soup. Russ & Daughters keeps ancestral food memory alive while brightening it with a gourmet flair you may not find on typical bris or bat mitzvah menus.

“We were stalwarts of keeping traditional bagels,” Niki recalled, about when she and Josh began as co-owners in 2009. “As the old-school bagel bakers were disappearing it became harder to find the quality we insisted on. When we decided to become bakers, it was Josh and me with a two-by-four plank and a Kitchen Aid mixer above the store. The first dozen bagels we made were a triumph. Now we make 500,000 a year.”

It may now seem obvious that she was meant to carry on the tradition, but Niki went through her own journey. In her twenties, after graduating from Amherst, and spending time at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Niki found herself living back above the shop on Houston Street, contemplating whether she wanted to join the family business full time, or go into the arts. She began an MBA at Yale, but quickly realized it wasn’t for her.

Inevitably, no matter where she was, people would regale her with stories of their love for Russ & Daughters, and their own family’s food traditions. It began to settle in her heart where she belonged. She joined forces with Josh, and they began their apprenticeship with Mark to learn the trade.

Now her days include tasks as varied as showing a German film crew how the Brooklyn Navy Yard bakery makes challah, lecturing MBA students on legacy food businesses, managing the logistics behind the scenes, or utilizing her slicing skills at the counter while meeting new customers.

The Russ legacy was the subject of the recent exhibition, An Appetizing Story, at the American Jewish Historical Society, which has acquired the archives of Russ & Daughters. Annie Polland, executive director of AJHS, sees the story through a historical lens. “The expectations of and opportunities for Jewish women have changed immeasurably since the time Joel Russ arrived in New York, but the Russ & Daughters story shows how women have keen business acumen,” said Polland.

“It’s as if Niki channeled her grandmother Anne, and her great aunt, was able to strike out on her own, and then applied it back to the business. This was an opportunity the granddaughter had that their grandmother had not. Yet still, the store allowed that energy to be transmitted through the generations. I think Niki and Josh both have a legacy and a responsibility to ensure that Russ & Daughters continues its amazing work, and that the transmission of its history—one in which women were so central—lives on.”

Since taking the helm, Niki has found a way to weave the strands of her passions for food and culture together. Russ & Daughters is regularly hailed by tastemakers like Martha Stewart, and the Café has been featured on the millennial cult favorite TV show “Broad City,” starring comedians Ilana Glazer and Abbi Jacobson, and hosts a music night at the Café with downtown icons such as Laurie Anderson, whose late husband Lou Reed was a loyal customer. Anderson also hosted the Café’s first Passover seder, now an annual tradition.

Jenji Kohan, a regular customer and creator of “Orange is the New Black” and “Weeds,” thinks the lure of Russ & Daughters is only enhanced by its owner. “Niki is simply impressive.” Said Kohan. “She’s taken the reins of this legacy business, grown it while keeping it haimish, and all with a smile on her face, small conversations that make everyone feel seen and heard, and a wicked way with a fish knife. She’s the coolest.”

Ruth Andrew Ellenson is a winner of the National Jewish Book Award for her anthology The Modern Jewish Girls’ Guide to Guilt, and a journalist whose work has appeared in the New York Times, Los Angeles Times and Washington Post.

- No Comments

July 9, 2019 by admin

The Foremothers of Food Memoirs

Food memoirs have been springing up like chanterelles after a rain. For 20 years or so, we’ve been treated to a harvest of life stories with recipes included; an Amazon search for “food memoir” turns up more than 2,000 entries.

Reading food memoirs may feel like eating dumplings (or maybe kreplach): they’re comforting, produced by people hailing from all over the world, and easy to love. Look at a few titles, and you’ll see the scope: Poor Man’s Feast; Treyf: My Life as an Unorthodox Outlaw (Elissa Altman); Lunch in Paris (Elizabeth Bard) and Talking With My Mouth Full (Bonny Wolf).

When, in the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s, Mimi Sheraton and Laurie Colwin, and later Ruth Reichl, were writing about the conjunction of food and family life, they were looking back in ways that anticipated and influenced the contemporary food memoirs.

“Food is like no other trigger, physiologically,” says Traci M. Nathans-Kelly about her 1997 study Burned Sugar Pie: Women’s Cultures in the Literature of Food. “It has a physical presence that something like a song doesn’t. It is one of the few things that are hard for people to forget. So, when you combine it with memory—people, places, things—it’s really powerful.”

Mimi Sheraton, author and New York Times restaurant critic from 1975 to 1983, can attest to that: “Food was so much a part of my life, so if I cooked, or longed for, a food that my mother made, it evoked a whole scene. …The tone of my family life informed the cooking, or the other way around. I always wanted to tell the story of my family as a surrounding for the recipes,” she told Lilith in a recent interview.

Sheraton’s book From My Mother’s Kitchen: Recipes and Reminiscences was first published in 1979. It alternates chapters featuring recipes from Sheraton’s mother with fond essays about growing up in a food-obsessed Jewish family in Flatbush, Brooklyn, in the 1930s and 1940s. “I just always conceived the book that way,” Sheraton said of its unusual format. It was practical, too: “We didn’t want to do memoirs first, then recipes,” or vice versa, Sheraton explained. “No one would read all of it!”

Sheraton’s mother was an experienced and skilled home cook, and while the book contains many classic Eastern European Ashkenazi Jewish dishes, like brisket, chicken soup, and farfel (egg barley), her repertoire also included non-kosher American favorites like shrimp Creole and chicken pie.

While responses to the memoir sections were “very, very positive,” From My Mother’s Kitchen “got an adverse reaction from Jewish organizations because it wasn’t kosher,” Sheraton recalled. Although she provided kosher substitutions, “B’nai B’rith started a letter-writing campaign” to the author in protest.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...