Tag : israeli women

January 16, 2020 by admin

Across the Barrier

Glorious blue skies stretched over Ruppin Street as I drove to the white brick building of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, adjacent to the Givat Ram campus of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. My chest prickled, seared skin healing from the radiation to my breast and across my chest to catch any remaining cancer cells left behind after my lumpectomy three months prior. I smelled like burn. Or did it just feel like I did? I had been spared chemotherapy, which felt like God the Woman acceding to my personal entreaty for a pass. She must have noticed that my hands, head and heart were carrying three small sons under five, including a baby I’d speed-weaned days after my diagnosis. The Mediterranean sun poured light onto the streets, the lush lawns, the nearby museums and government complex. Everything sparkled.

Except me. On the path to learning to live again, I was struggling, even stumbling. During the blurred weeks of surgery and radiation, what I’d thought of as my raw vitality and bounce had all but disappeared. I’d always exuded positivity. No more. Happiness felt like a distant country. What was the trick to getting the lilt back in my step? Was there a handbook on how to survive surviving?

That clear luminous Wednesday in March was one of my very first days as a breast cancer “survivor,” and even that label befuddled me. Was “survivor” the right term for a disease that could always recur, however unlikely? Trying to ward off a recurrence, I had signed up for countless support groups at the local center for breast cancer survivors, as if attending more would scare away the malignant cells and translate into more years added on to my life expectancy. I had put my name down for the English-speaking support group, the Hebrew-speaking support group, the couples support group, guided imagery, dance therapy, psychodrama, even belly dancing.

And that afternoon, I was trying something else. The Cope Forum brought together Israeli and Palestinian breast cancer survivors for support and exchange. It was started in 2000 by the JDC’s Middle East program, in partnership with Patient’s Friends Society, a Palestinian NGO, and the Israel Cancer Association. Conveniently, the Cope Forum met in a Jewish part of Jerusalem I knew well. I drove down the streets to the meeting with self-assured familiarity, relieved that I did not need to consider navigating an unknown Palestinian neighborhood in East Jerusalem.

Whiff. I blew cool air into my t-shirt, relieving my charred skin and knotted nerves.

I entered the building from a side entrance, and a security guard motioned me to a closed-door conference room. When I pulled open the heavy door to the nondescript room with its sepia-tinted photos of Jewish leaders, my jaw dropped.

Oh my! There are so many hijabi women in this room! Some 20 women with headscarves, clad in flowing caftans in vibrant blues, browns and maroons, holding paper cups of steaming instant coffee as they chitchatted in Arabic.

Muslim Palestinian women dressed in hijabs and abayas had filled my field of vision over the 20 years I had walked Jerusalem’s streets. But I had never been in a room with so many of them! Not at the Malcha shopping mall. Not at the Beit Sahour Israeli-Palestinian majority male dialogue group I’d attended for a few years.

Mind buzzing, my widened eyes didn’t know where to land. Ten Jewish Israeli breast cancer survivors— identifiable by their clothing (soft cotton shirts and casual pants or jeans, garb similar to what I was wearing)—were talking with Palestinian breast cancer survivors, and the room hummed with women whose body language radiated self-assurance. They carried their curves and scars with confidence and poise, as if their bodies had recorded disease and moved on. While I scrambled to recover a self stolen by cancer, these women had faces alight with vitality. I would later learn that they were all much further along in life-after-breast cancer, with diagnoses and treatment courses that had faded into memory. I wanted in on the secret they’d unlocked to surviving, forging ahead, undefeated.

My shoulders settled. Who were these women, and where were they from? East Jerusalem? Or the West Bank? My mind wandered, considering the differences in language, dress, and faith. These musings were luring me out of the stagnating loop in which I’d gotten stuck after cancer. It was a welcome diversion from my obsession with recurrence-menopause-hot flashes-dying young. At long last, I was distracted from myself.

While a facilitator introduced us to Qigong, a Chinese form of meditation and breathing, I stole glances at some Palestinian women standing next to me. My eyes landed on one in particular. Her heartshaped face was wrapped in a royal blue hijab, and there was kindness in her eyes. Her good spirits were matched by a playful grin.

As the facilitator led us through a warm up, swinging our arms side to side, the smiley woman quipped and cracked jokes under her breath in melodious Arabic, sending Palestinian women to her left and right into peals of laughter. She nodded in my direction, lips turning ever so slightly.

“Hey there,” she said to me in English. “I’m Ibtisam. Nice to meet you!”

“Same,” I smiled back. “I’m Ruth.”

To an outsider, both sides of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict intermingled in that room. But there was actually no conflict at all. We weren’t talking politics. The only apparent adversary was the cancer we were all battling.

After the Qigong activity, all the women socialized. Swapping stories in Arabic, Hebrew and even some English. Laughter that sounded throaty, strong, real. “Tfaddali.” Help yourself. Someone offered me a huge grin and a generous slice of homemade baklawa, leaving my fingers sticky.

In the corner, I balanced the pastry and arched my shoulders, adjusting the stretched white bra atop my prickly pink skin. It was a nursing bra. Apparently I hadn’t let go of my nursing self, even though the milk was long gone. Forever gone. Or perhaps it was myself I wasn’t done nursing?

But these women were past that. And their open smiles suggested that they had enough bandwidth to prop me up, too. In time, I would learn more about the challenges of Palestinian breast cancer journeys. The loneliness and isolation in their respective communities, the stigma of cancer, the concern about becoming a social pariah if they shared their medical history with others, the difficulty of traveling through checkpoints for treatment. And that one particular hijabi woman who stole laughter and merriment from wherever it could be found, Ibtisam Erekat of Abu Dis, would become like a sister to me, one of my dearest friends. Which she has remained to this day, nearly nine years later.

Two women scooted over to the side and unrolled prayer rugs. It was time for Salat al-zhur, the early afternoon prayer. After exchanging a few quiet words, they positioned themselves in the direction of Qiblah, in the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca. “Allahu Akbar.” As they prostrated their bodies, I thought to myself, Pray for me, too.

Suddenly it became clear. A door was opening. To other things, beyond this conference room, beyond the immutability of the Israeli-Palestinian divide, beyond disease. For once, cancer was expanding my world. In the easy togetherness, I felt solace, a blueprint of what could be. In that room, cancer was not only a disease; it was also the tie that binds.

I could have never imagined then that Ibtisam—a devout Palestinian Muslim who lived on the other side of the Separation Barrier—would become my person in Breastcancerland. That bit by bit, intimacy and kinship would be woven between us, transcending the divide. That in the nine years since that first meeting of the support groups she would become the one to nurture my hopes and caress my fears. Ibtisam would model for me how to “survive” breast cancer with humor and grace, and I’d also become her go-to person, the first friend she would call when her stepdaughter got engaged and the one to whom she cried when her mom passed away. I could not have known then that our friendship would weather the tension, complexity and storms of war, that we would serve as each other’s support system when violence reigned and blood was shed. During Operation Protective Edge, the Israel-Gaza war of 2014, when rockets rained down on Israel and airstrikes pounded Gaza, Ibtisam was often the first friend of mine to call to see how I was doing when sirens hit Jerusalem. And I rushed to call her when the news reported crossfire between soldiers and stone throwers in her hometown of Abu Dis.

In that first meeting, I caught a glimpse. Cancer wasn’t only going to close doors. It also had the power to open them. A disease which had felt to me like an end could actually be a sort of beginning.

Ruth Ebenstein is a writer, a historian, public speaker and peace activist. Her forthcoming memoir is Bosom Buddies: How Breast Cancer Fostered an Unexpected Friendship Across the Israeli-Palestinian Divide.

- 1 Comment

July 9, 2019 by admin

Kayama Moms •

In Israel, women up to age 45 qualify for the National Health Service free in vitro fertilization for two children. Now, not only secular single women, but also Orthodox single women have overcome stigma and chosen to become mothers. Kayama, founded in 2011, aims to create a community for Shomer Shabbat (religiously observant) families of single moms by choice, offering information, tools and support to accompany them from making the decision, to conception, pregnancy or adoption and beyond. Seminars include— pregnancy/adoption procedures, fertility for 35+ women, financial planning, parenting tips conducted by doctors, rabbis, educators, psychologists and experienced single moms. They also arrange Shabbat retreats and vacations for single moms and their children. kayamamoms.org

- No Comments

March 14, 2019 by Joan Roth

Women of the Wall Turns 30: Stunning Photos from the Scene

Last week, Women of the Wall celebrated its 30th anniversary of standing up in favor of egalitarian prayer at the Kotel, facing physical intimidation from ultra-religious protesters.

Lilith’s Joan Roth was on the scene, documenting vivid Torah readings, massive crowds, and even the paratroopers who helped capture the wall for Israel in 1967 who showed up to support the women.

- No Comments

July 15, 2014 by admin

The Art of Ornament

Bridal jewellery, Sana’a, Yemen, 1930s–1940s, silver and gilt-silver filigree and granulation, corals, coins, The Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

Israel boasts an exciting and very hip cadre of extraordinary visual artists, yet their work in jewelry design and fashion can elude the radar. Time to take notice! For many decades, this work —much of it by women —has been created in a fascinating space between cutting-edge and traditional, pushing the boundaries of how we think to adorn ourselves. Here, an introduction to some very dramatic “worn ornaments” made by women artists —in different eras and emerging from diverse cultures —since the founding of the State of Israel.

Jewelry in Israel (Arnoldsche Art Publishers, 2013) is a bravura book featuring more than 60 unique contemporary Israeli artist/jewelers by art historian Iris Fischof. This exceptional volume brings to international attention the astonishing diversity of talent, expertise and creativity of Israeli artists working in the format of jewelry objects. Fishof rightly contends that each artist’s voice is an individual statement clarifying the ‘idea’ of jewelry worn as adornment, as personal/political identification, empowerment, as status and prestige. The artists have been selected for their singular concepts and command of technique. Each is highly skilled, envisioning a sculptural form both wearable and thought provoking. Precious metals and gemstones have a low importance but texture, color, surface and pattern are used with ingenuity. Fishof clearly identifies the maker’s national background, academic affiliation, age and life events, careful not to label this diversity as the collective definition of ‘Israeli’.

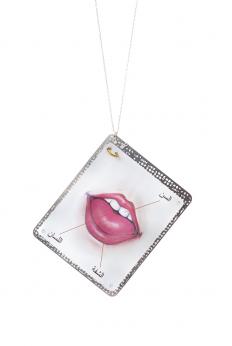

Deganit Stern Schocken, Mouth, pendant from the series “Figure of Speech”, 2011, stainless steel, polystyrene, gold, silver, zircon, nylon, cotton thread.

The subtitle of this book is one of its strengths, Multicultural Diversity 1948 to the Present, with chapters dealing on the ‘melting pot’ period of immigration, 1950–1970, international outreach, and support of fellow artists 1950–1970 and in the 1970’s, of world acclaim. Four of these jeweler/artists that found global recognition, are Bianca Eshel Gershuni, Vered Kaminski, Esther Knobel and Daganit Stern Schocken. The shared history of Holocaust, immigration, internal political strife, constant tensions both physical and psychological have led to a vocabulary of materials and images like none other.

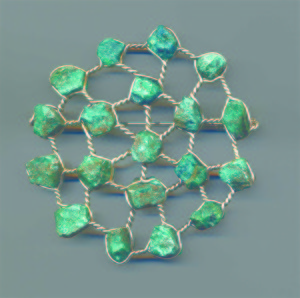

Gorgeous as much of this work is, it is the impact of such pieces such as ‘fish-airplane’ brooches by Gershuni, crafted during the Gulf War (1991), the repeated, referential use of metal webbing, a reminder of the windscreen protective mesh during the period of the Intifada attacks in 1987–2000, by Vered Kaminski and the motif of memorial wreaths for fallen protectors by amongst others, Michal Bar-On Shaish. These artists turned tragic events and industrial/found object materials into beautiful personal jewelry challenging the intent to annihilate and destroy. The most potent of Jewish symbols, the Magen David star is used sparingly, except in an inverted reference to the mandatory Nazi identity badge, the ‘yellow star/Jude’. Instead several artists including Zoya Cherkassy and Degnit Stern Schocken create positive I.D. brooches in delicately wrought 18k gold, turning a dangerous negative into praise worthy pride.

Vered Kaminski, brooch, 2010, silver, turquoise, presented by Israel’s President Shimon Peres to German Chancellor Angela Merkel, 2010.

Historically, jewelers evolved from family based workshops/ businesses. Jews were barred entry in any of the European ‘guilds‘ and trade associations commencing in the 14th century. Unable to learn professional skills, the outsider tradition of the self-taught passed generationally, inspired by native, local craft traditions and importantly included women as workers. Many highly competent women were the unseen, unsung anonymous fabricators of jewelry. Since the 1948 founding of the State of Israel, women have been accepted as equals on the battlefield, on the collective farms and in the jewelry studios.

Israeli support for the arts continues to grow, with the leading educational sources for professional jewelry/handmade objects being the Bezalel Academy in Jerusalem and the Shenkar College of Engineering and Design in Ramat Gan. In 2006, Edgar Bronfman created an annual prize, the Andy, in memory of his wife Andrea, herself a great collector and supporter of contemporary Israeli crafts. Recognition of this award is furthered by an annual solo exhibition in the Eretz-Israel Museum, Tel Aviv.

In singling out any of the more than 60 distinctive artists applauded in this volume I do so based on my many professional years in the contemporary jewelry world as a dealer, curator and collector.

These artists are featured in fine art galleries and contemporary museum jewelry collections throughout the world. The photography and art direction of this volume is of the highest order, appropriate for this sophisticated art book.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...