Tag : history

January 26, 2021 by admin

Goddesses You Need to Meet •

Female deities were often represented in the polytheistic world of the ancient Near East, and many later evolved as part of biblical monotheism. Problem is, after the Babylonian exile they were increasingly suppressed and the one God in the Hebrew Bible and the rabbinical interpretations acquires a “female side” as opposed to a divine female partner. An exhibition

created at the Jewish Museum Hohenems in Austria, expanded now at the Frankfurt Jewish Museum, combines art depicting female elements in God concepts with their cultural-historical traces in the three monotheistic religions. Evidence comes from ancient archaeological figurines, medieval Hebrew Bible illustrations, Renaissance paintings of the Madonna and interpretations by renowned contemporary artists, including Helene Aylon. “You Gotta Believe: The Goddesses vs. Moses,” an animated video by Nina Paley, humorously explores the theme of ancient female deities.

juedischesmuseum.de/en/visit/detail/female-side-of-god

- No Comments

July 27, 2020 by admin

We are Dying Because of the Fears of White People

Why are white people so afraid of my Black skin? When will living in this Black body feel liberating and freeing, instead of terrifying? When will this country acknowledge this pain? When will we have to stop running on the wheel of white supremacy? When will we be able to breathe?

I am exhausted, too. All the Black people in me are tired. […] We can’t get into an accident and knock on someone’s door for help. We can’t be too loud in our joy. We can’t be too Black. We can’t go birdwatching. We can’t say “I can’t breathe” and expect to live. We can’t be. We are murdered and blamed for our own deaths. We are tired of running. Tired of being told that we are not enough. Tired of constricting ourselves into tiny boxes. Tired of screaming “Black Lives Matter” at the top of our lungs. Tired of mourning and grieving those we’ve lost—those lost to gun violence, those who’ve slipped through the cracks in our society, those we’ve lost to Covid-19. We are tired.

My liberation is tied to your liberation. I want collective liberation. I need collective liberation. I need to feel free in this Black body. Black and Indigenous People of Color (BIPOC) need the time and space to dream, heal, and rest.

This is not a fight of our own creation. We are living and dying because of the fears and imaginations of white people. It is long overdue for white folx to join us in this fight. This feels especially relevant when the mainstream Jewish community continues debating whether Jews of Color exist, and cannot even have conversations about how Ashkenormativity in the Jewish community hurts Jews of Color.

It is no longer the time to stand on the sidelines and cheer us on (and it never was). If you love me, show me. Show me what the Jewish values of Tikkun Olam look like. Will you shield me with your body to protect me from the vicious blows that come from living in a white supremacist society? Will you move through the pain that comes with wading through 400 years of racist and white supremacist history to get to the other side with me?

Black people are magic. We make the impossible possible. We always were and always will be. It amazes me that despite the injustices, the maimings, the killings, and the collective trauma, we haven’t yet burned the world down. I suppose that given all our ancestors went through, we will not go down without a fight. Or, maybe we are just otherworldly and we’re here to inform you of new ways of being.

DENA ROBINSON, The Lilith Blog

- No Comments

July 27, 2020 by admin

Our Education is Never Over

“I am Jewish and I am American. I cannot divorce myself from the fact that the country that gave my family a future was built from slavery. I will continue to educate myself about interconnectedness to this land and its many peoples. As a rabbi, I will continue to raise awareness about mass incarceration and bail reform. If I am silent, I am complicit.”

RABBI MIRA RIVERA, “A Jewish Journey to Montgomery,” by Eleanor J. Bader, The Lilith Blog.

- No Comments

November 5, 2019 by admin

Speaking While Female •

Historically, women have been nearly absent from the record of public speaking, with their speeches seldom respected or remembered. In an effort to change that, a new initiative showcases women speakers from antiquity to the present, and around the world. Ida B. Wells on lynching. Rose Schneiderman on the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire. Alexandra Kollontai on revolution. Oprah at the Golden Globes. They’re all here, and hundreds more, with transcripts, video, and, in some cases, audio. Are there historically significant speeches by women you’d like them to include? Send suggestions to: info@speakingwhilefemale.co

- No Comments

April 30, 2019 by admin

In the Shadow of Notre Dame

Back in the 1970s when I was a graduate student in Paris, I started a couple of traditions for myself. Now, each time I’m in the city I spend some alone time just sitting in the left-bank’s Square René-Viviani just across from Notre Dame Cathedral, and each time I leave Paris I stand on the Petit Pont, toss a coin into the Seine, and promise to return. And return I do, time and again, for short periods and long to the city that has become my second home.

- No Comments

June 22, 2017 by admin

Reason, Desire, and a Deep Dive into Jewish History

One frustrating aspect of modern American culture—and its greatest divergence from Jewish culture—is its obsession with novelty, to the point of dismissing anything older than yesterday as worthless. The Weight of Ink (Haughton Mifflin Harcourt, $28), as its title suggests, is a counterweight to the world of Twitter: a story of words on paper and their uncanny endurance. This novel, by the immensely talented Rachel Kadish, is also a beautifully written meditation on reason and desire, a deep dive into Jewish history, and a riveting story whose weight stays with you.

Like A.S. Byatt’s Possession, The Weight of Ink’s plot hinges on a fantastic trove of manuscripts and the ego battles between scholars fighting over it. Helen Watt, a senior scholar recently diagnosed with Parkinson’s, learns of a stash of 17th century Portuguese and Hebrew letters in an old London home. The documents trace to London’s Sephardic Jews, a community traumatized by the Inquisition. Helen’s tremors force her to hire Aaron Levy, an insecure graduate student who resents Helen’s imperiousness, which he attributes to her non-Jewish appropriation of Jewish history. In fact Helen is scarred by a romance in 1950s Israel; Aaron likewise pines for a girl who abandoned him to make aliyah. Tensions between them initially turn The Weight of Ink into a novel of academic manners. But that’s not what Kadish is after.

When Aaron and Helen discover that the documents were produced by a rabbi’s female scribe, the book brings us into the life of Ester, a Portuguese Jewish orphan in 17th century London who becomes the ward and then the scribe of a rabbi blinded decades earlier by the Inquisition’s torturers. A talented scholar, Ester at 21 quickly realizes that as the rabbi ails, she will either have to marry or become a housemaid— in either case cut off from scholarship. But when a chaperoning job takes her to the Globe Theater, she is inspired to take on a new identity, disguising herself on paper as a man and writing to the great minds of her era— who then actually respond.

This launches the book into its real subject, which is less the content of 17th century thought (brace yourself for a primer on Spinoza’s pantheism) than the divide between the life of the mind and life as it’s actually lived. This may seem like an abstract topic, but it isn’t. For women, whose lives even today are often limited by mundane obligations, the gap between idealized beliefs and lived realities can be enormous. And for Jews, this gap is likewise more than theoretical. The Torah presumes we live in an imperfect world. Moreover, Jews in every era, including our own, have often been called upon to denounce their ancient allegiances, forcing many to compromise their beliefs or to choose between acceptance and integrity. As the book’s rabbi says, “The distances between things are vast”—referring to the physical space he blindly navigates, the social space between people, and the spiritual space left by God’s apparent absence.

If this sounds dense for a novel, it’s not. In The Weight of Ink, questions about God and reason find expression in Ester’s writings, but more often, Kadish dramatizes them through Ester’s experiences as a woman and a Jew, driven by a desire in both mind and body that her world forbids her. The choice between safety and integrity animates Ester’s every move—and she makes a lot of moves, intellectually and otherwise. As her interactions with non-Jews take on unexpected importance, she’s also forced to face the legacy of the Inquisition, which her community survived only by publicly denouncing themselves, leaving their children uncomfortable in their own bodies. For a book mostly set in a plague-ridden 17th century, it all feels weirdly familiar, a disturbing reminder of how much of our ancestors’ humiliations still live within us.

The book is not flawless. Kadish has the unenviable job of introducing an unfamiliar history; she mostly handles this with a light touch, but a few scenes read like Wikipedia entries. Likewise, connections involving major figures like Spinoza and Shakespeare can feel contrived on the page, as do several soapy plot twists that strain credibility.

These weaknesses would hardly be noticeable except that they are inconsistent with the rest of the book, which is rendered with the confidence of a master artist. Kadish writes with an incredible eye for the subtleties of emotion, and with countless gems of insight connected to the novel’s deeper themes. Here is Ester, for instance, contemplating her future: “[A]s she lay in the dark, a thought might rise murky out of the fatigue, and—she couldn’t help herself— she’d hold it tender as a newborn lest it slip from her hands, caressing it, trying to shield it against oblivion.” Here is Helen, contemplating hers: “She had seen early in life that there was none in this world to audit one’s soul… And if there was no auditor, one must audit one’s own soul, tenaciously and without mercy.”

Lines like these, thick with meaning and beauty, appear on every page. The intertwining of meaning and beauty in this novel at times feels too perfect, the balance between past and present storylines too idealized. Yet it’s a testament to Kadish’s talent that the novel’s ending, which ought to feel too neat, is immensely satisfying, a renewal of faith for characters and readers alike. Words on paper or screens only rarely last, but stories like Ester’s endure.

Dara Horn is a scholar of Yiddish and Hebrew literature and the author of five novels: In the Image, The World to Come, All Other Nights, A Guide for the Perplexed, and the forthcoming Eternal Life (January 2018).

- 2 Comments

October 7, 2014 by admin

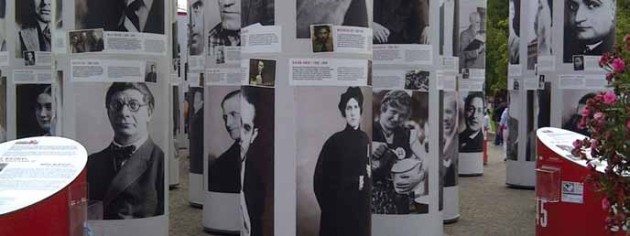

Before the World Was Ready

Rabbi Sandy Eisenberg Sasso (R) and guide in the Prauge Jewish Cemetery

The first women ordained as rabbis in the Unites States — Sally Priesand, Reform, 1972; Sandy Eisenberg Sasso, Reconstructionist, 1974; Amy Eilberg, Conservative, 1985; and Rabba Sara Hurwitz, Modern Orthodox, 2010 — traveled together to Berlin, Prague and Terezin in July to commemorate and learn more about the life of the first woman rabbi ever ordained. Lilith readers are familiar with the story of Regina Jonas, but new details surfaced during the poignant trip, which was organized by the American Jewish Archive and the Jewish Women’s Archive. Rabbi Eilberg shared these details on the Jewish Women’s Archive blog:

Rabbi Regina Jonas

“Regina Jonas, born into a poor Orthodox Jewish family in Berlin in 1902, dreamed of being a rabbi at the astonishing age of 11, far before the Jewish world was ready to support her aspirations. During the 1920s, she studied at the Academy for the Science of Judaism, taking all the same courses and exams required of rabbinical students, and wrote her rabbinic dissertation on the remarkable topic, ‘Can Women Serve as Rabbis?’ The faculty member who seemed ready to ordain her suddenly died and the institution agreed only to grant her the degree of ‘Academic Teacher of Religion.’ But in 1935, she was ordained as a rabbi by Rabbi Max Dienemann, representing the association of liberal (Reform) rabbis in Berlin. At first she was invited to work in schools, Jewish hospitals and nursing homes. As many rabbis fled the country, there was an unmet need for rabbis and Rabbi Jonas was able to serve in several synagogues that were desperate for rabbinic leadership as catastrophe approached. Regina Jonas was deported to Terezin in November of 1942, where she worked with psychologist Viktor Frankl in the camp before being deported to Auschwitz on October 12, 1944, where she was murdered.”

Rose Zoltek-Jick, a Boston law professor and Lilith board member who is the child of a Holocaust survivor, was one of the delegation of about 30 people who made the trip. She wrote, “It was far more meaningful than I could have ever anticipated. I knew that being surrounded by committed Jews would be the only way I could encounter the fears and ghosts that have shaped my being.

“[At the Berlin Jewish museum] it is unsettling (to say the least) to feel the clang of the door in Leibskind’s memorial that shuts you into a concrete tower with a crack of light and a ladder you could never reach; one descends into the maze of memorial stones created by Peter Eisenmann and realizes the hide and seek is not a game, if you are being pursued and you are not sure that there will be anyone waiting to find you at the other end. And it is quite another emotion to sit in Gestapo headquarters and know that you, a Jew, unlike one’s people just one generation ago, will walk out of there alive.

“At the same time, we had the honor of meeting Jews who have created a new rabbinic academy and its graduates who are serving in communities of small numbers all over Europe, and women rabbis who are creating the new norms that are necessary to reach out and spark any hope of renewal.”

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...