Tag : Hebrew

June 25, 2020 by admin

Israeli Bedtime Stories

My new immigrant mother and father didn’t read any bedtime stories. But, before putting out the light they recalled strange tales of Eastern Europe, where they were born. I could envision everything: a river frozen in the winter (I hadn’t ever seen snow), dark woods (I saw only pines planted by the Jewish National Fund), gray sky, so different from the sharp yellow light that surrounded me.

Strange words were whispered: “shtetl,” “Hasidic,” “Yiddish.” But we already loved In Hebrew and cursed in Hebrew, wearing short khaki pants and our bodies embraced by the unforgiving sun.

How could my parents replace their old lives? How did they find their way to this almost forgotten land? I remember myself cuddled in bed, trying to figure out the mystery. My mother never mentioned the Holocaust, yet I always knew about Auschwitz.

Under the fragile layer of new life was another story, not meant for young ears. An invisible page, burning with great pain and loss. I can see myself covering my head, threatened by this nightmare, letting my imagination run loose. Perhaps my mother and father had secret wings and flew to Israel? When I grew up I made this vision into my book, Flying Lessons.

Nava Semel was born in Israel and has published seven books and three plays. Two of her books are available in English, Becoming Gershona (Viking Penguin) and Flying Lessons (Simon & Schuster).

- No Comments

January 16, 2020 by admin

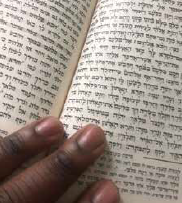

For Jews of Color, by Jews of Color

I remember a time not long ago in which I could read Hebrew, chant it, recognize words, but not understand the text before me. I remember visiting Orthodox cousins and watching them davening, a flurry of words on their tongues. In contrast, my immediate family could not speak a word of Hebrew and, for a long time, Hebrew remained a mystery language to us. At times growing up it was difficult to feel ownership over my Jewishness. I remember being told as a child that I was not even Jewish by a person who simply looked at my mother, who is Filipina and Jewish, and made an assumption.

Particularly outside of Orthodox spaces, Hebrew and Jewish education in this country are inaccessible at best, and unnecessarily expensive. Hebrew is by no means the best or only Jewish language, but it is one that can grant access to a wealth of Jewish texts and histories spanning time periods and continents. The distinctly American myth that adults cannot learn new languages impedes access to Hebrew courses. The pervasive idea is that if you did not or could not access Hebrew or Jewish education as a child, if you do not have the yichus, the background, as some might say, then you will not be successful. Jews of Color have as many individual experiences as there are Jews of Color in the world, but the JOC community includes many adult learners wanting a Jewish education who are particularly likely to fall through the cracks. When you add pervasive racism, which exists even in the most progressive majority-white Jewish spaces, Jewish learning spaces that do exist can still not be the right place for good learning to occur.

So my friend and colleague Yehudah Webster and I co-founded Ammud, the Jews of Color Torah Academy as a space for Jewish education for Jews of Color by Jews of Color.

ARIELLE KORMAN, “Why She Needed to Create the Jews of Color Torah Academy,” on the Lilith Blog.

- No Comments

October 3, 2018 by admin

First Grade, Second Language

The words swirl around me, full of sound, empty of information. They are words in a language I don’t quite understand, and my translator, P’ninit, is not here to help me.

The words swirl around me, full of sound, empty of information. They are words in a language I don’t quite understand, and my translator, P’ninit, is not here to help me.

The other first graders are animated, speaking excitedly, and I am on the other side of their linguistic wall, straining to piece out meaning. Six years old, an American in Israel, where my father is on sabbatical, I am still citizen of another language. Comprehension ebbs and flows. Sweet, friendly P’ninit speaks some English, and she is usually my ambassador to this new reality, granting me access to a small group of girls who teach me words in the playground during morning recess, or allow me to shadow their activities, perhaps in the hopes that one day I might really be able to join their play.

Every day my mother walks my brother and me down the long street from our apartment, around the corner and up the steeply slanted hill to the city bus, where she deposits us, steeling her faith that this public vehicle will get her six- and seven year olds safely to their school a few miles away. This is how it’s done, in Israel, and she will not give in to her American instincts to hold our hands until she can pass us off directly to our teachers. We hustle in amongst the populace; other small children make their way along the route, and we all descend, day after day, miracle after miracle, and find our way to the grownups we still need.

It is raining this morning, thick, driving ropes of rain, but the bus arrives on time and we part uneventfully. When I arrive in class, I look for my friend, but she is nowhere to be seen. The other children have news, important news, but it is news that surpasses my vocabulary. There is a strange, unfamiliar energy in the room, and it frightens me.

All I have to hold onto on this confusing day are the words that my classmates keep saying insistently: P’ninit meitah, P’ninit meitah. I don’t know the word meitah. It is just an empty vessel to me, one that I am sure my mother will be able fill with meaning when I get home. She will clear up the mystery. She will help me make sense of P’ninit’s absence, just as she has helped me with so many other questions in this still foreign land.

But when I arrive home, the word has vanished, inexplicably, from my memory. I say nothing, hoping that P’ninit will be there the next day, and that there will be no need to go through the exercise again.

At school the next morning, I wait expectantly, scouring the doorway, but my friend does not come. I follow the other little girls to the play area at recess, but they do not speak English, and when I am with them, I still feel alone.

When I come home, I tell my mother that P’ninit has not been to school. She asks, carefully, if I know where she is. I don’t remember the word, I tell her. But I promise myself that I will find out.

A few days later, I muster up the courage to ask, in Hebrew, one of the girls in our group where P’ninit is. I am not really asking where she is, though. I am looking for that verb, the one that might still save me.

P’ninit meitah, she responds, patiently, quizzically, with a sigh that is so much older in English than it is in Hebrew. I fold the word meitah tight in my mind, zipping it into a mental pocket. I don’t write it down—though I could have, I know how to do that. I repeat it over and over in my head, trying to make it stick. Meitah, meitah. I clutch the syllables as I make my way to the afternoon bus, quietly taking a seat next to my brother. I try to keep it echoing as he chatters, down the street and around the bend. But during our stop to climb the knotty branches of the carob tree on the corner, the word manages to free itself from my grip. Up the elevator to our tenth floor apartment I find myself searching in the corners of my mind for where it could have gone. As I run through the front door to greet my mother, I realize that the word has escaped once again, and my question can no longer be formed.

In the meantime, my mother knows. She heard the radio the day it happened, the rain still coming down in angry sheets outside her window. A six-year-old girl, hit by a bus that skidded over the curb on its way to a stop. The broadcast in resonant, full throated Hebrew, a language used to announcing impossible news.

P’ninit does not return. But we are not ready, my mother and me. Not ready to affirm the cruelty of the world to each other. Not ready to make the horror real by allowing it into language.

In my classroom, I stitch meaning together on my own, mostly in solitude. I don’t ask questions, I just take everything in, wide-eyed, ears perked. Slowly but surely, I awaken into Hebrew. I can talk to the other girls now, make sense of the lessons most of the time. I learn to speak and I learn to read.

My mother calls another parent and hears the whole story. She weeps to my father, with loss and fear and loneliness, unsure of where she belongs.

Weeks go by, then months. I spin through the pages of the Hebrew book on my father’s lap faster than he, a professor, can keep up. My accent matches that of the Israeli children around me, and I slide unthinkingly between the Hebrew of my city and the English of my home.

One day, I am sitting at the dining room table, having my afterschool snack of chocolate tea biscuits and milk, and, simple as that, the word pops into my head. I remember, I tell my mother. The word I keep forgetting. Meitah, what does P’ninit meitah mean?

It means she died, my mother tells me, her nose turning red. She was hit by a bus on a very rainy day, a horrible accident.

But I know this already.

I do not reel in shock, or burst into tears. I tuck my first Israeli friend, lovely dark haired P’ninit, round cheeks and bright brown eyes, back into the elusive word. I put her gently away into the space between my English and my Hebrew consciousness, the place where loss can’t exist, because it cannot be spoken.

My mother lets me do this. It’s easier that way.

Rachel Mesch teaches French literature, history, and culture at Yeshiva University in New York.

- No Comments

September 26, 2018 by admin

Israeli Kids in the U.S. •

To cultivate a connection to Judaism and encourage Hebrew language learning and knowledge of Israeli culture among Israeli families who live in the United States, the Israeli American Council offers Israeli children’s books, selected by educators for children ages 2–8, to any family signing up for this service. An annual subscription is $10 for seven books, plus activity kits based on the books, and additional resources. israeliamerican.org/keshet/ hebrew-books

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...