Tag : health

January 26, 2021 by admin

A Seal of Sustainability

A program designed to support organizations and communities working to create a healthier, more equitable and more sustainable world for all, links Jewish values to substantive action toward sustainability and climate-centered goals. Receiving the Hazon Seal of Sustainability means that your organization or community has committed to and taken substantial action on two or three projects focusing on greening initiatives or sustainability projects over the last 12 months.

Apply at seal.hazon.org/about.

- No Comments

January 26, 2021 by admin

Safety—and Desire

Researchers at the University of Windsor, in Ontario, are working to deliver a “Flip The Script” program to women in high school…. The conversation moves beyond consent to sex—pleasurable sex, at that. The young women talk about female sexual anatomy, masturbation, desire and a persistent phenomenon known as the “orgasm gap”: Time and again, researchers find women are significantly less likely to masturbate to orgasm or climax during

partnered sex than men. “The more comfortable we are with being able to talk about sex, the more assertive we will be in communicating what we want, as well as what we don’t want,” the exercise reads.

“Part of this is, if I know what my own sexual desires and values are, then I can know that when someone is pressuring me, they are wrong to do so,” said Charlene Senn, a University of Windsor psychology professor who originally designed Flip the Script for women in first-year university.

Slowly, sexual health educators are beginning to go beyond disaster prevention to encompass healthy, positive sex lives, in line with the World Health Organization’s definition of sexual health: “pleasurable and safe sexual experiences, free of coercion, discrimination and violence.”

Perhaps the bleakest portrait of neglected female desire comes from journalist Peggy Orenstein, who interviewed young women aged 15 to 20 about intimacy for her 2016 book Girls & Sex: Navigating the Complicated New Landscape. Most of the young women had come to view sex as a performance, not a “felt experience….The concern with pleasing as opposed to pleasure was pervasive.”

—

ZOSIA BIELSKI, from “The pleasure gap: How a new

program is revolutionizing sexual health education

for young women,” The Globe and Mail, December

5, 2020.

- No Comments

July 27, 2020 by admin

We’re Going to Witness a Surge in the Current Health Inequality

MARION DANIS is a physician and bioethicist who directs the Bioethics Consultation Service at the National Institutes of Health. The views she expresses here are her own and not necessarily a reflection of the policies of the N.I.H. or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

The coronavirus pandemic feels like a throwback to an era when human capacity to overcome diseases was minimal. We revert to ageold techniques—isolation, hand-washing, masks. The novelist Orhan Pamuk, who knows a lot about how it feels to live through plagues (he’s read many of the great novels about past plagues as he has been writing a new one), tells us our experience is similar in some ways but different in others. We fear the unknown, we start rumors and blame others for bringing the plague. But unlike the experience of past plagues, we aren’t in the dark; we can know what’s going on everywhere in great detail, and we avoid the full impact of isolation by connecting virtually. We are relying on the biological sciences to eventually find more modern solutions.

In the U.S., the healthcare system will be in a sad state after we have made our way through the pandemic. This will not be solely due to the outbreak but also due to policy decisions made before the pandemic, and during it.

Millions of people will have lost their jobs and will lose their employment-based health insurance as a result. Many people who worked in the gig economy without an economic safety net will be unable to afford the basic elements needed for health, particularly safe housing and adequate nutrition, and will not be able to afford healthcare without incurring debt. Many medical practices will have faced economic hardship and even closed, and healthcare practitioners will have lost jobs because all routine, non-emergency medical care will have gone on hold. We will witness an exaggeration of health inequality because death rates from Covid-19 have been higher among minority communities. We will recognize how important maintenance of public health infrastructure is and what a mistake it was to allow a lapse in preparedness for pandemics.

It will take remarkable optimism to see much good coming out of this pandemic. But perhaps the consequences will be so dire and the urge to fix the problem will be so great that we will urge or even insist that Congress pass legislation to create guaranteed income and expand health insurance, and demand that the executive branch plan better next time.

- No Comments

April 1, 2020 by Rebecca Katz

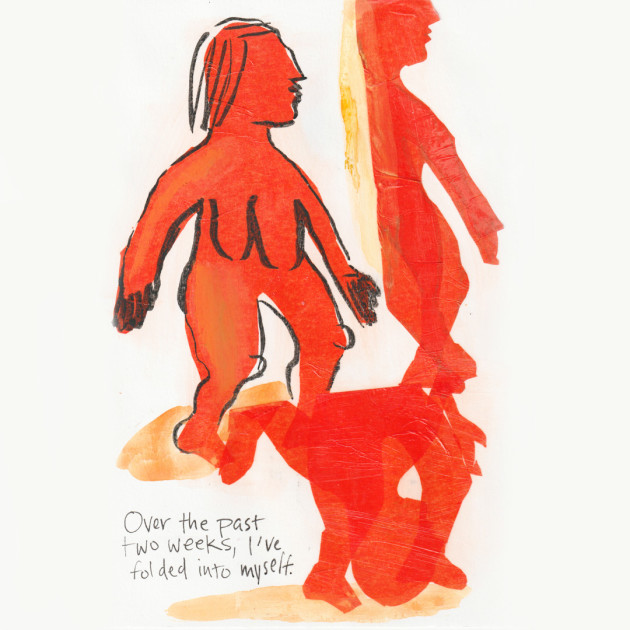

Migraines in Quarantine: A Comic

I’ve never tried to draw my migraines before. Then again, I’ve never lived during a pandemic before, so there are so many new things happening in my life. I found my couple of weeks working from home busier and more stressful than before the crisis, but without my normal valves to control my anxiety. It all erupted in a fantastic migraine that kept me company for many days.

- No Comments

January 20, 2015 by admin

New Books on Reproductive Justice: IVF, the Pill, Sex, Feminism, and Katha Pollitt

In vitro fertilization — I.V.F. — is an assisted reproductive technology in which an egg is fertilized by sperm outside the body, and then implanted back in the uterus. Because it is often seen as the court of last resort for an individual or a couple addressing infertility, many news reports about I.V.F., even those purporting to be scientific, are framed as stories about families; they are private and personal, often tinged with tragedy, fear, or desperation. Prior to reading Biological Relatives: I.V.F., Stem Cells, and the Future of Kinship (Duke University Press, $26.95) by Sarah Franklin, I too thought of I.V.F. as a procedure that may have originated from science but was firmly rooted in the emotional realm.

However, Franklin’s rigorously researched and exhaustive look at “the normalization of I.V.F.” grounds the procedure firmly in technology and science, not to mention philosophy, anthropology, agriculture, feminism, and history. The first chapter alone includes multiple references to Marx and a brief journey through the Industrial Revolution, and while the connections do not always seem obvious, Franklin makes a persuasive case for just how large a debt I.V.F. owes to events and innovations that occurred hundreds of years in the past.

Biological Relatives is, first and foremost, an academic book. The language can be dense and complicated, and from the very first page Franklin assumes a certain level of knowledge on the part of the reader. Yet Franklin’s analytical tone serves her material well, because it allows the reader to focus on how truly significant I.V.F. is as a technology and how far-reaching its continued use is — not just for those that have been personally affected by I.V.F. but for anyone with an interest in reproduction, feminism, gender equality and sexuality. As Franklin succinctly puts it, “In vitro fertilization is at once a technique, a model, an imitation of a biological process, a synthetic process, a scientific research method, an agricultural tool, and a means of human reproduction — of making life. It is an experimental model system with more than one life of its own.”

The final chapter of this book deserves a special mention, as it includes Gina Glover, a photographer whose work includes a number of photographs inspired by I.V.F. technology. Neckties are reshaped and composed to represent sperm; hens’ eggs, in pairs and alone, are cushioned in knitted cozies; pairs of geneticists’ striped socks, lined up in a grid, are meant to mimic the chromosome strands photographed during genetic testing of a developing fetus; pre-implantation embryos are transposed onto images of stars and galaxies. Glover’s photographs, as Franklin puts it, depict “a new frontier of biological relativity in which the social, the biological, and the technical are lived ambivalently together,” and the inclusion of these images allow Biological Relatives to conclude on a deeply profound and surprisingly moving note.

No less profound is Seizing the Means of Reproduction: Entanglements of Feminism, Health, and Technoscience by Michelle Murphy (Duke University Press, $23.95). Like Franklin, Murphy is an academic. Her book is at the same time more accessible and narrower, choosing to devote its four chapters to answering a series of questions raised in the introduction: “How did reproduction, health, and feminism come to be so intimately connected in the late twentieth century’s shadow of the American empire? …How were local feminist projects…made possible by larger historical conditions? … How does feminism’s targeting of reproduction signal the centrality of sex to the emergence of present-day forms of governmentality?”

To answer these questions, Murphy looks at the rise of feminist health collectives and health practices in the U.S. during the 1970s and 1980s. Her fast-paced chapters take the reader deep into this world, and don’t shy away from examining both the tensions within this period of feminist activism and the barriers to a more patient-centered form of health care in the country as a whole. Murphy acknowledges the roles that race, class, and socioeconomics played in the feminist health movement. For instance, she offers a succinct summation of how two very different groups of feminists — predominately white women in Los Angeles and women of color in the Boston area — chose to address race and economics in their work and in their missions. Murphy doesn’t pass judgment; rather, she allows the reader to make up her own mind about the benefits and drawbacks of their decisions, and her neutrality serves her material and readers well.

The events that Murphy writes about are more than three decades old, yet it is startling to realize just how relevant these questions are today. Much of the activism explored in Seizing the Means of Reproduction arose, at least in part, out of a desire to put reproductive healthcare decision-making in the hands of those most affected by it: women themselves. But, as the current social and political climate around women’s rights, gender and reproduction makes clear, these issues continue to incite controversy and judgment today. And this knowledge adds a surprising poignancy not just to Seizing the Means of Reproduction but also to The Birth of the Pill: How Four Crusaders Reinvented Sex and Launched a Revolution (Norton, $27.95) by Jonathan Eig.

The “four crusaders” of the title are reproductive rights pioneer Margaret Sanger; scientist Gregory Pincus; Katharine McCormick, a wealthy widow; and John Rock, a Catholic ob/gyn. Sanger spearheaded the project and approached Pincus to develop a birth control pill; several years into the project Pincus, in turn, approached Rock for assistance with the medication’s clinical trials. And all of this work benefited greatly from both the financial and ideological support of McCormick, a contemporary of Sanger’s. Working at times together, at times separately, all four overcame substantial social, scientific, political and religious obstacles in the name of giving women a private and reliable way to have greater control over their fertility and, by extension, their lives.

Given that we all know the outcome of the story, The Birth of the Pill is surprisingly suspenseful. Neither Sanger nor McCormick had easy personal lives, and while Pincus’s wife and children were accepting of his all-consuming work, his professional life was far from simple. Even Rock, a man who enjoyed a loving family, secure career, and respectable place in society, had to reconcile the teachings of his religion with his sincere belief that contraception was necessary for happy and healthy families.

Eig carefully balances an abundance of medical and scientific information with enough personal detail to make the actions and decisions of all four principals understandable. And he doesn’t sugarcoat those actions, or the people behind them. Sanger could be “abrasive” and “obstinate,” clashing at times with the leadership of Planned Parenthood, the organization she helped establish. For his part, Pincus’s single-minded focus on his work likely helped cost him a professorship at Harvard, and also jeopardized the financial health and stability of the scientific institution that he helped found and run.

Eig also does a skillful job of making it clear to contemporary readers just how monumental was the very idea of this kind of contraception during the years of the pill’s development, which began in the 1950s and was not fully completed until the ’60s. It was no secret that a birth control pill taken only by women would give those women control not just over their reproduction, but over their sex lives. “Sex for the pleasure of women? … [I]t was dangerous. What would happen to the institutions of marriage and family? What would happen to love? If women had the power to control their own bodies, if they had the ability to choose when and whether they got pregnant, what would they want next?”

Those questions weren’t mere rhetoric when Pincus and his colleagues began researching oral contraception in the mid-20th century. And they’re not mere rhetoric today, either, as Katha Pollitt makes clear in her new book Pro: Reclaiming Abortion Rights. (Full disclosure: While I don’t know Pollitt, our paths have crossed professionally. I interviewed her years ago, and she both gave my own book a positive blurb and included it in Pro’s “Further Reading” section.) While it’s public knowledge that abortion is becoming harder to access in many parts of the United States, what is less-often discussed is the very language that even those who identify as pro-choice use to talk about abortion. As Pollitt writes in her introduction, “Anywhere you look or listen, you find pro-choicers falling over themselves to use words like ‘thorny’, ‘vexed’, ‘complex’, and ‘difficult’.” Yet this narrative ignores the fact that for many women, having an abortion was not a painful or difficult decision. Consistently casting abortion in a negative light allows the speaker to judge an unknown woman, and assigns an unnecessary and unasked-for weight to a personal medical decision whose very legality is wrapped up in the right to privacy.

In eight brisk chapters, Pollitt makes a well-argued case that abortion can be “a moral right with positive social implications.” She dismantles many of the anti-choice movement’s arguments and justifications, but her greatest achievement may be in her engagement with the “muddled middle,” those who think that “abortion should be legal, sort of, but it’s wrong, sort of, and it shouldn’t be too easy, and it shouldn’t be too late, and the woman needs to think about it more, but also not wait too long, and most of all she should not be such an irresponsible slut.…” Her focus on this audience — and on their assumptions, concerns, and stereotypes — allows Pollitt to place abortion and reproductive rights in the larger contexts of sexual equality, education, public health and parenthood. While Pollitt is far from the first person to make these connections, Pro is a timely reminder that despite the many scientific and medical advances around reproductive rights, the rights themselves cannot, and perhaps should not, be taken for granted.

Sarah Erdreich is the author of Generation Roe: Inside the Future of the Pro-Choice Movement. She lives in Washington, D.C.

- No Comments

April 16, 2013 by Chanel Dubofsky

Early Abortion: A Papaya Workshop

I’m a little concerned that the bags under my eyes might be permanent, but more than likely, they’ll go away soon.

I’m a little concerned that the bags under my eyes might be permanent, but more than likely, they’ll go away soon.

This happened last year, too, when I spent two and a half days in the hermetically sealed radical bubble that is the CLPP (Civil Liberties and Public Policy) conference.

My adrenaline is so high all day that it takes me hours at the end of each day to settle at the end of every day that it takes me hours to settle down enough to sleep, and when I can sleep, I resent it, because it takes me out of the space.

CLPP is held every year at Hampshire College in Amherst, Massachusetts. The full title of the conference is: From Abortion Rights to Social Justice: Building the Movement for Reproductive Freedom. It brings together folks (read: troublemakers) to strategize, present, discuss and build around reproductive justice.

On Friday, April 12th , I got on a bus in New York at 8 am, singularly (creepily) focused on getting to CLPP by 4 pm, which is when the first workshop slot of the conference began. I had planned to attend “The Papaya Workshop: An Introduction to Early Abortion,” presented by the Reproductive Health Access Project, since seeing the conference schedule. In the workshop, we would watch a simulation of an options counseling session, and learn how both early abortion procedures work, including a demonstration of a manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) abortion on a papaya.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...