Tag : grief

October 23, 2020 by admin

Why Did the Funeral Procession Cross the Road? •

I brought my hand to my heart. The voicemail was from David, at Levine’s Chapel in Brookline, MA, one of the most thoughtful funeral home directors I have the somewhat unusual privilege to know. As a rabbi it is not unusual to get a call from a funeral home director; the rabbinate is a vocation where you make plans with friends with the caveat that you’ll show up as long as no one dies.

“Rabbi,” David said, “It’s a social call. I heard you have big doings coming up on Sunday and I wanted to wish you Mazel Tov!”

I breathed out and smiled. Loss and grief, joy and gladness: a Jewish sandwich that has somehow sustained us across the ages.

We never planned to get married in the Hebrew month of Av. My partner Matan and I were to be married at the end of May. It was a date specifically chosen because it was Rosh Chodesh, the first day of a new Hebrew month of Sivan, and represented my love for how our Judaism lives by the cycles of the moon. But perhaps more importantly, we chose this day because it wouldn’t conflict with my rabbinic duties. It would have arrived at a time where I had more chances to slow down and breathe.

We never planned to get married in the Hebrew month of Av, the month in our calendar that commemorates and collates our collective loss, historic and modern. From the tragic loss of the Temples in Jerusalem through centuries of expulsions, the nine days before Tisha b’Av are not days for joy or dancing the horah.

Nonetheless, thanks to Covid 19, our Ketubah wedding contract reads as such. “On the 5th day of the Month of Av…” It was on that day, July 26th, that we created our very own little Eden in the middle of Jamaica Plain, Boston. Some of our siblings and friends were present, masked and physically distanced. Our parents and all other guests joined via Zoom.

Rabbinic sages debated what to do when loss and grief and joy and gladness meet. The Talmud offers a scenario where a funeral procession and a wedding procession meet in the center of town.

Idiomatically explained best by 11th century Rashi, “When the bride comes out from her father’s home to the wedding hall at the same time [as] those accompanying a dead body for burial and both groups will be shouting—one group with joy and the other

in mourning and we don’t want to mix the two, we reroute those accompanying the deceased…”

So, when a funeral procession—or a pandemic taking a global toll on human life—and a wedding party meet in the narrow streets of Boston, who gets to go first? Jewish sages teach us that when the two meet, we reroute our grief, because joy and gladness get the right of way.

But why did the sages believe this? Were it up to me, I would rewrite the Talmudic text and do some construction work to widen the way so that when a wedding and a funeral meet on the streets, the two processionals could share the road. For when I stand with congregants at a funeral there is often laughter mixed with tears, a deep sense of gratitude and celebration of life. When I stand with congregants at a wedding, there is also often loss and grief. Grief for those whose absence is palpably felt, sorrow for letting go of children who have grown, and I can’t help but notice the smiles of those who witness with joy but long for a love of their own.

What the rabbis of the Talmud nudge us to imagine is this: the beloveds cross the road to their chuppah, and the mourners in the funeral procession look out from their sadness through the car window, for a split second they see one another and look each other in the eye. Because we must witness them both, equally, but then allow joy to lead the way.

So our Ketubah says Av. And honestly, it has felt like we’ve been in the month of Av for 5 months now, so why postpone joy any longer?

RABBI JEN GUBITZ

- No Comments

June 25, 2020 by admin

The Book under My Pillow

When my beloved grandmother died, I was inconsolable. However, the book Bubby, Me and Memories by Barbara Pomerantz (UAHC Press, 1983) was a great comfort. The book is illustrated with photos, and I looked at them over and over, amazed that there in a book was a little girl who looked like me. I pasted photos of me and my bubbe in the blank pages at the beginning of the book and slept with it under my pillow. I was 33 when my grandmother died, and the little girl in me will always be grateful for having found a book that expressed her sorrow.

Leslea Newman’s books include several titles about Jewish girls and women and their grandmothers: the children’s book Remember That; the novel In Every Laugh A Tear; and the forthcoming children’s book Matzo Ball Moon.

- No Comments

October 3, 2018 by admin

First Grade, Second Language

The words swirl around me, full of sound, empty of information. They are words in a language I don’t quite understand, and my translator, P’ninit, is not here to help me.

The words swirl around me, full of sound, empty of information. They are words in a language I don’t quite understand, and my translator, P’ninit, is not here to help me.

The other first graders are animated, speaking excitedly, and I am on the other side of their linguistic wall, straining to piece out meaning. Six years old, an American in Israel, where my father is on sabbatical, I am still citizen of another language. Comprehension ebbs and flows. Sweet, friendly P’ninit speaks some English, and she is usually my ambassador to this new reality, granting me access to a small group of girls who teach me words in the playground during morning recess, or allow me to shadow their activities, perhaps in the hopes that one day I might really be able to join their play.

Every day my mother walks my brother and me down the long street from our apartment, around the corner and up the steeply slanted hill to the city bus, where she deposits us, steeling her faith that this public vehicle will get her six- and seven year olds safely to their school a few miles away. This is how it’s done, in Israel, and she will not give in to her American instincts to hold our hands until she can pass us off directly to our teachers. We hustle in amongst the populace; other small children make their way along the route, and we all descend, day after day, miracle after miracle, and find our way to the grownups we still need.

It is raining this morning, thick, driving ropes of rain, but the bus arrives on time and we part uneventfully. When I arrive in class, I look for my friend, but she is nowhere to be seen. The other children have news, important news, but it is news that surpasses my vocabulary. There is a strange, unfamiliar energy in the room, and it frightens me.

All I have to hold onto on this confusing day are the words that my classmates keep saying insistently: P’ninit meitah, P’ninit meitah. I don’t know the word meitah. It is just an empty vessel to me, one that I am sure my mother will be able fill with meaning when I get home. She will clear up the mystery. She will help me make sense of P’ninit’s absence, just as she has helped me with so many other questions in this still foreign land.

But when I arrive home, the word has vanished, inexplicably, from my memory. I say nothing, hoping that P’ninit will be there the next day, and that there will be no need to go through the exercise again.

At school the next morning, I wait expectantly, scouring the doorway, but my friend does not come. I follow the other little girls to the play area at recess, but they do not speak English, and when I am with them, I still feel alone.

When I come home, I tell my mother that P’ninit has not been to school. She asks, carefully, if I know where she is. I don’t remember the word, I tell her. But I promise myself that I will find out.

A few days later, I muster up the courage to ask, in Hebrew, one of the girls in our group where P’ninit is. I am not really asking where she is, though. I am looking for that verb, the one that might still save me.

P’ninit meitah, she responds, patiently, quizzically, with a sigh that is so much older in English than it is in Hebrew. I fold the word meitah tight in my mind, zipping it into a mental pocket. I don’t write it down—though I could have, I know how to do that. I repeat it over and over in my head, trying to make it stick. Meitah, meitah. I clutch the syllables as I make my way to the afternoon bus, quietly taking a seat next to my brother. I try to keep it echoing as he chatters, down the street and around the bend. But during our stop to climb the knotty branches of the carob tree on the corner, the word manages to free itself from my grip. Up the elevator to our tenth floor apartment I find myself searching in the corners of my mind for where it could have gone. As I run through the front door to greet my mother, I realize that the word has escaped once again, and my question can no longer be formed.

In the meantime, my mother knows. She heard the radio the day it happened, the rain still coming down in angry sheets outside her window. A six-year-old girl, hit by a bus that skidded over the curb on its way to a stop. The broadcast in resonant, full throated Hebrew, a language used to announcing impossible news.

P’ninit does not return. But we are not ready, my mother and me. Not ready to affirm the cruelty of the world to each other. Not ready to make the horror real by allowing it into language.

In my classroom, I stitch meaning together on my own, mostly in solitude. I don’t ask questions, I just take everything in, wide-eyed, ears perked. Slowly but surely, I awaken into Hebrew. I can talk to the other girls now, make sense of the lessons most of the time. I learn to speak and I learn to read.

My mother calls another parent and hears the whole story. She weeps to my father, with loss and fear and loneliness, unsure of where she belongs.

Weeks go by, then months. I spin through the pages of the Hebrew book on my father’s lap faster than he, a professor, can keep up. My accent matches that of the Israeli children around me, and I slide unthinkingly between the Hebrew of my city and the English of my home.

One day, I am sitting at the dining room table, having my afterschool snack of chocolate tea biscuits and milk, and, simple as that, the word pops into my head. I remember, I tell my mother. The word I keep forgetting. Meitah, what does P’ninit meitah mean?

It means she died, my mother tells me, her nose turning red. She was hit by a bus on a very rainy day, a horrible accident.

But I know this already.

I do not reel in shock, or burst into tears. I tuck my first Israeli friend, lovely dark haired P’ninit, round cheeks and bright brown eyes, back into the elusive word. I put her gently away into the space between my English and my Hebrew consciousness, the place where loss can’t exist, because it cannot be spoken.

My mother lets me do this. It’s easier that way.

Rachel Mesch teaches French literature, history, and culture at Yeshiva University in New York.

- No Comments

September 27, 2018 by admin

Fiction: In Rhodesia

AS SOON AS HER FATHER DROVE THEIR rental car out of the Meikles Hotel garage, Laura felt that they were outside the protective shell of the hotel lobby, its white walls and marble doors, golden brass chairs and chandeliers, glass crystals dripping from the ceiling. The streets were gray and gritty. If not for the sea of black faces they could have been in an American city, with its busy, crowded streets, tall office buildings you had to crane your head back to see the tops of, and people in a rush to get somewhere. Only 10 minutes later, they had left Harare behind and entered the dry maize-colored land of the bush. Boundaries crossed so effortlessly. Just as only this morning they had own into Harare, stepping straight onto the tarmac from the plane just as her parents told her they had done when they left the country in 1977 for America.

“We are in the bush now,” her father said. When she heard her father say “the bush,” she expected to see wild animals herding past, stampeding bison, a lone elephant. She expected something more exotic than dusty, at land, looking like the Midwest plains except for an occasional bare tree, standing alone, poised as if in a Japanese watercolor.

She kept waiting for her parents to explain things. Usually her father was the one to ll the silence, to tell stories, jokes, but he was quiet, preoccupied. They must be thinking about her brother. Didn’t they care that it was her first time back to the country of her birth?

She felt that familiar feeling of not being able to access her parents’ thoughts or emotions, of a barrier between them. She forced herself to think of her brother, of what she knew of him. When she was a little girl, she used to imagine him sometimes as a bearded angelic figure, stepping down magically from the attic to protect her and express brotherly love. All her life she wanted to be someone’s favorite, for someone to love her most of all.

As if her mother sensed she felt ignored, she said, “Those white bundles are bird’s nests.” She pointed to tufts of white so spun straw buried in the limbs of some of the bare trees, like white cotton candy.

Her mother spoke with the assumed certainty of a tour guide, and she, Laura, was the tourist, the only one who had never really lived here. She had been only two years old when they left, too young to think of this as her homeland. Were her parents thinking about her brother’s death now? They never spoke about it. When she thought about her brother, it was only her parents’ pain that she imagined. She could feel no emotion herself towards this brother she had never known. Only the strange realization that if he hadn’t died, she would not have been born.

Now she was looking outside at a countryside that belonged to her in some way, but she felt empty inside, at and dull like the land outside. This didn’t feel like her birth place; she had no connection to it.

Back home in Long Island, her mother would sometimes bring out a red leather album of photos of her house in Rhodesia: “Would you like to look at pictures of my garden?” she would say, sounding like a little girl showing her treasures, opening the album to reveal photos of herself, newly married, standing in her garden, the tropical bougainvillea, wisteria, jacaranda and rose bushes towering over her with their petals and vines, everything in bloom, the flowers, and her mother, her face breathing in their smell, smiling patiently and happily as if to say, I am young and beautiful, and this happy life, my family’s life, among the lovely flowers will continue forever. In the photo her mother wore a white dress, cinched tightly at the waist and blooming out at the hips, her breasts full to bursting, ready, as if full of milk.

“These were my roses, the tallest roses in Salisbury,” her mother said when looking at the photos of her garden. To young Laura the roses looked towering, as if there were a jungle, a rainforest, in her mother’s backyard. Her mother, a transplant herself, born in Frankfurt, Germany, had arrived as a baby in Salisbury straight o a boat in 1939, and as a young mother had conquered this foreign African soil, learned how to make things grow in the dirt.

When her mother showed her these pictures, it was as if Laura was being let into another life, a world and a past that did not include her. Her mother never said that she regretted coming to the States, yet surely the patch of earth in their backyard in which her mother planted herbs and vegetables, and the circular bed in the front yard around a big oak tree in which she planted tulips in the spring, impatiens in the fall, must have been a let-down from that beautiful garden. If they had stayed, her brother, almost 12 at the time, would have been drafted into a civil war. To risk losing his life for a cause, Zimbabwean independence, that they did not believe in, did not make sense.

Her mother was the one to make the choice. She had lost one son accidentally and was not going to lose another. They were lucky to get out when they did. “If it had been up to Daddy,” her mother said once as they paged through the photo album, “we would never have left. You should always know when it’s time to make a change.”

THEIR CAR WAS NOW IN FRONT OF THE cemetery gates. A sign said Warren Hills Cemetery. The gates were black iron and looked 10 feet high, designed to keep something or someone dangerous out, or possibly to protect what was within. The trees and grass behind the gate were thick, green and lush, in contrast to the relentless dull ochre of the bush. A black man nodded at them, opened the gate, waved them ahead. Her father drove down the dirt path.

The earth was a reddish clay, and little clouds of red-tinted smoke stirred up around her parents’ feet as she followed them out of the car. Her legs felt heavy. She felt dread for the first time she could remember. She didn’t want to see the grave. She didn’t want to follow her parents. What was the point? Duty, obligation, doing the right thing.

“Laura, come on, don’t move so slowly,” said her mother.

Just ahead of them, four black men in white clothes were digging, making holes for graves, or filling in the holes of newly dug graves. They stood several feet away from each other, working fervently as if there were many more graves to dig and not enough time. She didn’t see any Jewish stars on these graves. A thin layer of red smoke wafted into the air around the men. There were no mourners there, just men digging fast, no time for ritual. Just enough time to dig a hole and put the coffin in before the next dead body arrived.

Her father said, “Those must be all the AIDS deaths.”

As they passed, one of the men looked up, paused. The bright whites of his eyes like moons, he looked right at her, nodded, and said, “Good afternoon, young lady.” He spoke in such clean diction, sounding almost English. “The Jewish cemetery is ahead, up on the left.”

She felt uncomfortable. He wasn’t here to mourn anyone but he knew that she was. Ahead of them she could see neat rows of tombstones, gray marble and granite, sticking straight out of the earth like obedient powers. Each had a Jewish star engraved in the top center of the stone. There were more Jews buried here than Jews still living in Zimbabwe. Almost all of the Jews, like them, had left. For a better life. In search of what they had originally come here for, crossing oceans, continual motion. Her own cousins were in Australia, England, Israel. Her family’s graves were scattered across the globe, a diaspora of the dead.

She thought of the yahrzeit candle that once a year on the anniversary of her brother’s death her mother plugged in on the white stand in their narrow front hallway, its Jewish star orange and pulsating. She never saw anyone actually plug it in. It somehow magically appeared on the yahrzeit days, then quietly disappeared before dawn. She would come home from school, see the glowing star, aflame within in the glass, and think, this must be the day that he died. She never said anything. There were a few other days during the year when the candle was lit. But she knew her brother had died in June, a few days before his birthday. Her parents didn’t say anything about her brother on these days; they hardly ever spoke of him.

Once, she had pushed, trying to break into the silences, and asked her mother if she thought of him often and she had said, “Every day.” She remembered being shocked. Every day? That her mother had these thoughts every day, of which she had no clue, 30 years after her brother’s death— did she not know her mother at all? How much of her mother’s life, she wondered, remained hidden within her, only revealed if she asked the right questions?

AS THEY WALKED CLOSER TO THE Jewish graves, their feet kicking up red clouds, she trailed behind her parents, sensing her parents didn’t want her to walk beside them.

She looked at her parents and saw that they were now holding hands. She couldn’t remember having ever seen them hold hands before. She had never felt so alone. Weren’t her parents supposed to take care of her, to comfort her? Now she saw them bend down, almost in unison, like one body, and then with their free hands, like dancers executing a move, each of them took hold of a small white stone from the ground.

“Take a stone, Laura,” said her mother. Why did she have to be told? Was her mother only going to speak to her to instruct? Still, she bent down to pick up a stone. She rubbed it and felt how smooth it was. What was really the point of this stone? She knew it had something to do with respect, duty, Jewish ritual. But a stone felt lacking, empty, dead. It just sat dumb and cold in her hand.

Her parents stopped in front of a small, unassuming gray tombstone. There were larger tombstones around, tall ebony and marble pediments, but so many of these small ones. Her father put a stone on top of the tombstone. Her mother lay down a stone next to her father’s.

She tried to imagine what her parents were thinking. She had thought from time to time of the awful pain of her parents upon coming home from a Saturday night out, returning home happy to that quiet house, imagining the children asleep in bed, or maybe they opened the door into a house filled with wails, the wails of the African woman who was their nanny, then discovering their eldest son, age 11, whom they had said goodbye to earlier that night with maybe a quick kiss, now dead on the floor, having choked on his late night snack because the nanny forgot to make sure he took his medicine for the epileptic

SHE STOOD NOW BEHIND HER PARENTS, still holding hands, their heads tilted down, angled towards the grave. From the back, her parents looked so frail, so slender and pliant, like two entwined plants, bending towards the grave for comfort as if towards the sun. She clenched and unclenched her fingers around the stone, wishing she had someone’s hand to hold.

Suddenly a sharp, high noise came out of her father’s throat. It was something wild. It sounded like a dog’s yelp when his tail has been stepped on. He raised his hand to his throat, clutching it, as if he wanted to stop another cry from emerging, as if he were choking. Her father’s sobs seemed to fill the air; they seemed as if they would last forever, like the at land of the bush that they had passed through. The sounds were ugly, raw, inconsolable.

Her father embraced her mother, sobbing. Then he was quiet. Her parents stood, holding each other. Still leaning on each other, they looked down at her brother’s grave. They didn’t even know she was there. She had misunderstood. They didn’t really care about her. Maybe they didn’t really love her. She was an obligation, something they had to care of. They had thought they wanted a child in their old age, to make up for her brother’s death, but it had been a mistake.

Suddenly her father turned around to face her. He was standing right in front of her now.

“Laura,” her father said. Laura, Laurence—her whole life that had been what she shared with her brother, the only thing she shared with him, a direct link, her name given in memory of his, the constant reminder that she had followed him, her life was meant to honor his, and that if not for his death, she would not be here.

“Daddy?”

“I have something to tell you.”

Her father embraced her. Her mother was still standing by the grave, facing it. Her father’s body was overcome by shudders and his sobs went right through her, shaking her along with him, as if his sobs were her own; his tears fell, warm and wet, on her cheek.

Her father moved his head back a few inches so that he looked right into her eyes. “I see him in you,” he said. “I’ve never told you this, but I see him in you. I always have. I hear him in your voice, see him in your face. Every day.”

The words washed over her, each phrase smacking her like a small wave. He spoke as if these were words that until this moment had been stuck inside of him, words spoken as a revelation, a consolation. So they were connected beyond a name, she and her brother. But she felt sorrow pressing down on her.

Her father looked at her, his eyes wide, imploringly, as if awaiting a response, expecting some words. She wanted to tell him that she felt a burden now. But she didn’t say anything.

“Hannah, I just need a minute.” He walked past her mother in the direction of their car.

Her mother was still facing the grave. Then she turned towards Laura.

“It’s time to leave. I’ve said everything I needed to say,” her mother said. She looked at Laura. Her eyes were dry. “It’s easier in life to be like that, to cry,” said her mother. Laura wasn’t sure what she meant at first. Then she realized she was talking about her father. Still, she wondered, did her mother want to be like that but was unable to?

“I can’t cry,” she said to her mother. “I want to. But I can’t.”

“That’s because you’re like me.” Her mother meant—strong, not overly emotional.

She wanted to say no, she wasn’t like her. But for all she knew, maybe she was. She looked back at her brother’s grave and said to herself, goodbye. She knew this probably would be the last time she saw his grave, the last time she visited this country.

Her father was up ahead of them. He looked steadier somehow, more solid, as if shedding those tears had strengthened him.

“We need to go wash our hands,” her mother said.

She followed her mother to a low gray stone wall where there was one silver metal spigot. Her mother turned the spigot until water came out of the faucet. Her mother put her left hand under the water, the reddish dust running over her hands, along the stone sink and into the drain like faint blood. She rinsed her right hand until it was clean. She turned the water off.

“We wash to leave the dead behind,” her mother said. Laura turned the spigot and felt the cold water wash over first one hand, then the other. The ritual was comforting. Her hands were clean. As they walked past rows of Jewish stars flagging the red African dirt, she took her mother’s cool, moist hand and held it in hers, and in this way they gave each other comfort.

Laura Hodes writes for the Forward, and has been published in Slate, the Chicago Tribune and Kveller.com. A version of this story will appear in her novel-in-progress, Arrivals and Departures.

- 1 Comment

April 17, 2018 by admin

The Accidental Archivist

Things do not exist without being full of people.”

— BRUNO LATOUR, THE BERLIN KEY

WHEN I WAS A TEENAGER, my parents died a few years apart, and as I went through the rituals of laying them to rest, well-meaning people assured me that I would “always have the memories.” There were the memories, which I couldn’t seem to hold on to, and there was my parents’ stuff, which I could actually hold: a half-empty jar of moisturizer my mother used to soothe her radiation burns, new polo shirts that my dad bought but didn’t live long enough to wear, a Post-it note with a phone message on it—the last thing my father ever wrote.

Death turns everything into an heirloom.

Getting to know my parents better was no longer a possibility, but like an archaeologist, I could investigate their belongings for answers to questions I hadn’t thought to ask when they were around. Letters sent to my grandmother chronicle my dad’s adjustment to leaving home; a business card tells me about his first job out of school; a snapshot of a handful of scraggly perennials shows me the pride my mother took in the humble beginnings of the garden I knew so well. And like the curator of a tiny and very specific museum, I could comb the archives for whatever selection of items seemed most relevant to my station in life at the time. I took up running in college, and I trained wearing my mom’s jacket. I polished my shoes for my first office job with my dad’s shoe brush. I pried the backs off the picture frames and replaced photos from my childhood with pictures from my travels. I cut up my mother’s wedding dress for an art installation. Surely my parents would not have wanted me to feel bogged down by their possessions, but neither would they have wanted me to forfeit the comforts to be had in keeping them around.

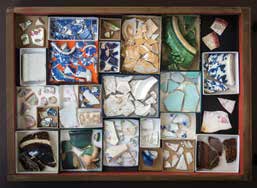

Image above from the series Garbagekammer (2016), a collection of the lost and discarded possessions of her house’s previous occupants unearthed from the backyard

At times, however, the sheer volume was overwhelming. My first apartment (not to mention a storage unit I rented) was full of the kinds of things no 21-year-old would own. My slowness to whittle it down felt like a character failing, an inability to part ways cleanly with the past or successfully integrate it into my present. But I was plagued with guilt, and sometimes regret, at parting with their things; there is a kind of emotional violence in detaching from the past after having been untethered from it by fiat.

Cultural expectations also fed into my dilemma. Despite the trendy infatuation with paring down one’s belongings to only those items that “spark joy” (per the internationally renowned Japanese organization guru Marie Kondo), certain strongly held beliefs persist about what should be kept in this scenario—“ good” china, a passport, a wedding gown, a valuable painting. Virtual strangers have expressed horror at the idea that I might do anything with these items other than store them indefinitely, compounding my fear that I might someday look around and realize I’ve done it all wrong. So I lived with, and paid to store, a motley collection of objects, which felt like too much stuff and also like never enough.

With each successive move through adulthood, I have managed to edit my permanent collection. I have a few regrets, like the dress I wore to my mother’s funeral, which she had taken me to buy several weeks before her death. I couldn’t bear to wear it again. But it was also the last thing she ever gave me. It sat untouched in the dry cleaner’s plastic for a few years, until finally I donated it to Goodwill, where it would be just another black dress with no clues to its provenance.

In the last few weeks of her life, when everything she told me took on an outsized importance in my mind, my mom explained that it was important to preserve bad memories along with the good ones. She might have wanted me to keep that dress. But like so many other things, I won’t ever know.

Just as grief is open-ended, so too is my relationship with all this stuff. I have come to embrace my roles as archaeologist and museum curator: their creative component, their imperative to make sense of objects with complicated histories. All this clutter—what the minimalism evangelists would have us throw out—offers new opportunities for connection with my parents, long after their perfumes and punch lines have faded.

A year ago my husband and I moved into our first home with a door wide enough to admit my parents’ kitchen table. The table is too large for the narrow room in which it sits. It’s bulky and awkward, but in its own way, it fits.

The work of artist Spencer Merolla is, as she states on her website, concerned with bereavement: “the material culture of mourning, and objects as repositories of memory which both retain and transmit meaning.”

Image above from the series Garbagekammer (2016), a collection of the lost and discarded possessions of her house’s previous occupants unearthed from the backyard

- No Comments

May 6, 2014 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

Jill Smolowe on Four Funerals and a Wedding

Jill Smolowe, author of “Four Funerals and a Wedding.” (Courtesy Phyllis Heller)

Jill Smolowe, a journalist and memoirist, had her own annus horribilis, only hers lasted a year and a half. In that short span of time, she endured the deaths of her beloved husband, Joe, her mother-in-law, and her own mother and sister. Smolowe kept waiting to fall apart in the wake of such loss, and yet she didn’t. Some untapped reserve of strength and resilience kept her going, and able to find meaning and even joy again. In this interview, she shares her hard-won wisdom about grieving with Lilith fiction editor Yona Zeldis McDonough.

YZM: What made you decide to write and publish your book Four Funerals and a Wedding?

JS: Like so many Americans, I had a set idea that grief involves specific stages. Yet I went through no denial, anger, bargaining or depression. Instead, as I lost my husband, sister, mother, and mother-in-law over a period of 17 months, my focus was on putting one foot in front of the other and figuring out how to reconnect with the joy in life. The more friends told me I was “amazing,” the more I wondered if there was something wrong or abnormal about my sorrow. Then I came across the work of George Bonanno, one of the country’s leading bereavement researchers. That’s when I learned that Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’s five-stage cycle of grief has long since been discredited. (She intended her cycle to apply to the dying, not the bereaved.) Research from the last 20 years identifies three distinct groups: those who are overwhelmed by grief upwards of 18 months; those who recover within 18 months; and those who return to normal functioning within six months, and even within days. This last group is labeled “resilient” and–surprise, surprise–these people constitute a majority of the bereft. My book aims both to put a face on this group and to challenge misconceptions and assumptions about grief.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...