Tag : Gen Z

January 25, 2021 by admin

Retail Work in the Pandemic Is Hell

CHAYA HOLCH, 22

Home Haven (name changed), a local, family-owned home goods store, is as close to an old-fashioned department store as it gets these days, with three-and-a-half floors and an array of products that one customer jokingly described to me as “everything you didn’t know you didn’t need.” I begin my work days there by wiping down the catalog keyboard, shared pens, label makers, and pricing guns with sanitizing wipes, then sanitizing my own hands before using the scraper usually reserved for getting gum off the floor to remove dried globs of hand sanitizer from their landing place directly beneath the automatic dispenser.

I, too, sanitize my hands intermittently, although as the day goes on, I remember to do so less and less between tasks. I straighten my magnetized employee badge, greet and make eye contact with customers, try to smile so widely beneath my mask that they can still tell I’m smiling, that I’m ready to help. My feet ache whenever I stop to remember them. A shocking number of customers, required by Vermont law to wear a face covering in the store, seem oblivious to the fundamental science of how masks can keep us safe during this pandemic, slipping their masks beneath their noses and even chins once they’ve entered the store. My coworkers are mostly women about my age, college students and recent graduates. We share leads about other jobs in the area, bemoaning our inability to find work in our preferred industries. Like many people our age right now, we have endured months of professional rejection and share an overwhelming fear for our futures.

Customers come in looking for all kinds of things: slotted spoons, toaster tongs, banana hangers, English muffin slicers, tart dishes, woks, whiskey glasses, 16-piece dinnerware sets, canning equipment. In some ways, it makes sense that people are purchasing so many home goods right now— if we are all spending more time at home than ever, why not buy new baking supplies and cocktail glasses? But it still feels awful to interact with a steady stream of customers looking for frivolous items while the pandemic rages, and to engage with so many people who are “just looking.” The knowledge that so many people are going about their lives as if the pandemic is not happening, or barely happening, is almost heartbreaking. I want to tell everyone to hurry home.

Recently, a mysteriously sweaty young white man came in looking for a beverage container. When I showed him our selection of gallon and two-gallon dispensers, he was dismayed, then explained, “Need bigger. Having a party.” Pause. “Wanna come?” I wanted to ask him what world he’s living in. I wanted to yell that I wanted my life back, too, but guess what? Instead, I shook my head and walked away, leaving him to contemplate his choices.

Chaya Holch is a New Voices fellow at Jewish Currents.

- No Comments

January 25, 2021 by admin

Cohabiting in a Pandemic

KIRA YATES, 23

One night in January, we saw a rat in my boyfriend’s kitchen. We heard it first, strutting between the pots and pans and knocking spoons off the countertop. Then, it emerged. We watched it waddle across the floor and burrow beneath the sink, fearless.

We gave it a name: Big Boy.

“Oh yes,” my boyfriend’s landlord admitted. The centuries-old farmhouse, located at the border of Cambridge, was no stranger to pests. The walls were thin and the rooms were drafty, full of holes to patch and fixes to be made. The landlord tutted and poked at the fire in the woodstove.

“We need to get rid of them,” Michael said, “They’re eating the food in the pantry and—”

“Oh, don’t mind the boys, Michael!” his landlord chuckled, shuffling the Sunday paper in his hands.

That night, we drove through the slushy city snow to my apartment with another pile of Michael’s clothes in the back seat. “I just—” he paused and smirked at me. We stared at each other, wide-eyed: “Don’t mind the boys, Michael.”

And just like that, I knew that I would never let him sleep next to Big Boy again.

On February 1st, we ate Chinese food on the rug in the living room of our new apartment, because that is what young couples do in movies and because we didn’t own any furniture yet. Our muscles were tired from carrying boxes up and down the stairs, from finding water glasses buried beneath cutlery and pie plates. We listened to a podcast about a new virus in China, and remembered the swine flu a decade before. “I had it,” I told Michael. “In the sixth grade, I brought it home to New Hampshire from a Massachusetts mall.”

“It was just a fever, like a little flu,” I added. I took another bite of lo mein and lay on my back. A moment later, Michael joined me. We stared at our living room ceiling, white and blank, like it was the night sky.

“What if we don’t get along?” I asked.

“We won’t,” he answered. “I think that’s part of it. Think of it as a social experiment.”

As March wore on, the trains grew less crowded. The beginning of my day had been punctuated by being pressed against the window of a train car, steeping in the smell of perfume and baby food and the fragile cardboard scent of grocery bags from Trader Joe’s. And then one day, all the people who owned cars grew scared enough to drive them. The last of us on the train forged a sort of camaraderie— the bond of those who had no other choice.

“I feel so lost,” I told my mom over the phone as I walked home from the train.

“I know, baby,” she answered. “Part of that is the world. And part of that is being 23.”

Michael worked from home even before the pandemic, and each day I returned from work to find him waiting for me. I would close the door, breathe in the smell of home, and collapse onto his chest before my work bag slid off my shoulder and onto the floor.

At night, we would ask into the dark, “Can you sleep?”

Undoubtedly, the other would answer, “No.”

Google automatically suggested a chart of virus data by state on the Covid Wikipedia page whenever I tapped on the search bar.

We took turns panicking. One read new articles while the other cupped their face in their hands, snorting in disbelief that we had front row seats to the end of the world. The scariest headlines, featuring droves of unmasked protesters at conservative political rallies, reminded us of Michael’s old landlord: “Don’t mind the boys.”

When, we asked, would someone “mind the boys?” It was like watching a house catch fire, only to hear the trapped occupant share how much they loved the smell of barbecue.

As the months wear on, and the virus continues its rampage, I have no great insight to offer. I refuse to allow the deaths of over a million people worldwide be a channel for my self-discovery. No, being lost in an age of loss is how I am spending my 23rd year, and likely my 24th. We’ve been forced to make a home in it—all of us. May we always be so lucky as to find love waiting for us at the door.

Kira Yates, a writer who works in development at a Synagogue in Boston, is a former Lilith Intern.

- No Comments

January 25, 2021 by admin

A Performer Forbidden Her Audience

ILANNA STARR, 25

I am an opera singer. It has been almost a year since I last entered a concert hall, performed for an audience, or had an in-person rehearsal. My industry has been forced to close all doors, cancel performances and wait.

I know this is what we have to do to protect artists, neighbors and loved ones. Yet, the uncertainty of when we will meet again in person has left me and most of my colleagues worried about careers we have spent our lives training for, and the future of the arts that give our lives meaning and beauty.

Today, my version of working from home means daily vocal practice, perfecting my diction in more than 10 different languages, learning new roles and repertoire, and creating and participating in virtual projects. All of this work, normally done in the company of teachers, coaches and colleagues, now takes place through my computer.

The transition to virtual life has rendered artists unable to make music with others in real-time and be heard, transforming the collaborative process of music making. Yes, technology affords some semblance of musical collaboration, but singing along with a karaoke track is challenging and confining, even after months of acclimatizing to this new reality.

I had taken for granted the fact that an audience would always be there to engage with, that I could make music together and in real-time with colleagues, and that I could learn and train in the same room as my teachers and coaches. This pandemic has amplified for me something I have long known: that my life has been fueled and energized by collaboration.

On my own, I have developed new skills. I have created a home studio to record projects, and learned more about sound engineering. I have grown my voice studio online and cherish the hours of the week that I get to share with my students. I have had more time to practice music that I love from all different genres and to better understand myself as an artist.

There have been so many days when I have been too overwhelmed by the state of the world to sing, days when words of encouragement to support fellow singers and friends are impossible to muster, and days when I have been consumed by existential questions and hopeless realizations about the future of performing arts.

But beneath these despondent moments, I believe that when our world opens up, people will pour into venues everywhere. So, though it would seem prudent to pivot and find a more lucrative career, I am more resolved than ever to continue honing my craft. It is extremely challenging to be an artist right now, but when this is all over my colleagues and I will be there to remind you of live art’s unique value—and how much you missed it.

Ilanna Starr is pursuing a Master of Music in Voice & Opera Performance at Northwestern University.

- No Comments

January 25, 2021 by admin

Is Gen-Z Alright?

Ten feminists, ages 18 to 27 squint at the future imperfect through a coming-out journal, religious faith, long-distance love, an opera career on pause, working retail to survive, and more.

From top left: Chaya Holch, Tziporah Herzfeld, Ilana Starr, Rachel Fadem, Rena Yehuda Newman, Kira Yates, Makeda Zabot-Hall, Abigail Fisher, Noa Wollstein, Arielle Silver-Willner

- No Comments

January 25, 2021 by admin

A College Senior During Covid Waits for the ‘After’

NOA WOLLSTEIN, 21

I left college as a second-semester junior, not knowing if I was coming back. While the class of 2020 was pitied for losing their graduation and final moments with friends, I envied them their near-complete four years at school. My senior fall has since gone online, and there’s no indication of a different fate for the spring.

Sitting alone in a house in Long Island, as my family members returned to in-person work, I’ve struggled to adjust to the new normal. I’ve been told to think of the future, when the pandemic inevitably ends and life, in one form or another, continues. The problem is that I have no idea how to look ahead. My classmates and I are back to living like high schoolers, but with thesis deadlines.

The road of school and education—from primary to middle to high to higher—that I’ve been on for so long is coming to an end. The big unknown beyond May was always supposed to be scary, a haze with the words “the rest of your life” floating in it. Still, I had bargained on having a framework for these last months before I enter “the real world.” It’s an interval of time short enough to make me panic-scroll through job listings, but long enough to stop me from actually applying to any of them.

I can’t visualize a future where I still study beneath stained glass library windows, go to rehearsals for my dance company, or live within walking distance of all my friends. And while I know (or hope) new joys will fill the life I build for myself after graduation this spring, how can I predict what they’ll be? How do I see the little moments that make living sweet, when I don’t know what I’ll be doing or where I’ll be living? Who even knows if I—or anyone else in my class—will have a job?

When school shut down in March and my dad drove me home a few days later, it felt dramatic to think of the moment I left campus as the end of life as I knew it. Yet in a sense it was: more than seven months later, I’m still waiting in limbo, holding my breath until I find solid ground again.

By now I imagined that I’d be getting through this year by embracing the unknown. As that moment of enlightenment has yet to arrive, so for now my solution is a little less ambitious. I’m focusing on midterms, taking up embroidery, and trying to take the day one hour at a time. Eventually, piece by piece, that will bring me to the future.

- No Comments

January 25, 2021 by admin

Battling Depression in Quarantine

RACHEL FADEM, 19

This September, I moved back to New York City, where I’m in school, and began online classes. With the new expectation that we should be performing our best, even with the restraints of the pandemic, my hard-won equilibrium from the summer faded. I missed large chunks of days from constant dissociation. I felt inhuman.

It took me about a month to recognize something was really wrong. My therapist asked me if I had any thoughts of death during one of our sessions. At that moment, I realized that I had been repressing serious mental health issues because I wanted to be “okay.”

I debated dropping out of school for the semester. I just couldn’t seem to deal with my responsibilities. I texted a friend because I needed to vent, and I knew that she would to listen. She called me and spent her night helping me make a plan for my mental health.

As we talked I realized that, in an effort to keep up with internships, student club boards, running my handcrafted jewelry business, and writing for pleasure—all on top of being a student and trying to manage my health– I had put too much on my plate. Since that conversation, I’ve been making an effort to emphasize self-care over my other responsibilities. I have been able to get more done, and I’ve been feeling better about my life, my future, and the world around me. I would still consider myself depressed, but I’m functioning. It’s the small victories that count.

I’ve been making a conscious effort to take every opportunity I can to find joy. If I don’t have anything due the next day, I spend my nights cooking for myself, doing an activity I enjoy, looking to my community to find comfort.

Now, even though I’m stuck inside for most of the day, I tell myself that I’m not alone. This pandemic has been difficult for so many and what we are able to produce or accomplish during this crisis does not determine our value.

—

For anyone in a crisis text HOME to 741741 to connect with a Crisis Counselor.

Rachel Fadem is a Lilith intern and NYU sophomore studying journalism and gender and sexuality studies. She hopes to one day get paid to write about rape culture and sex work through a feminist lens. When she isn’t busy with school or working at Lilith, you can find Rachel listening to the You’re Wrong About podcast and making earrings.

- No Comments

January 25, 2021 by admin

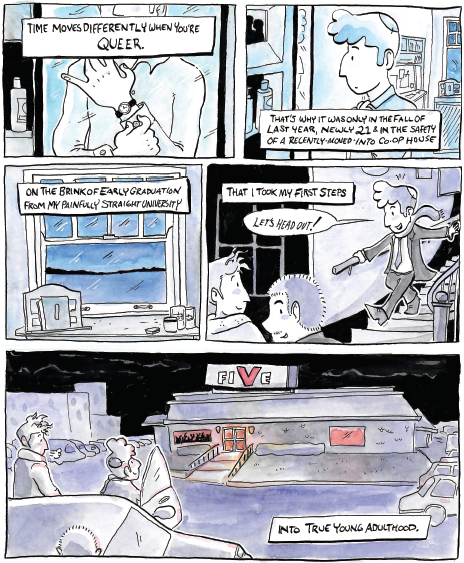

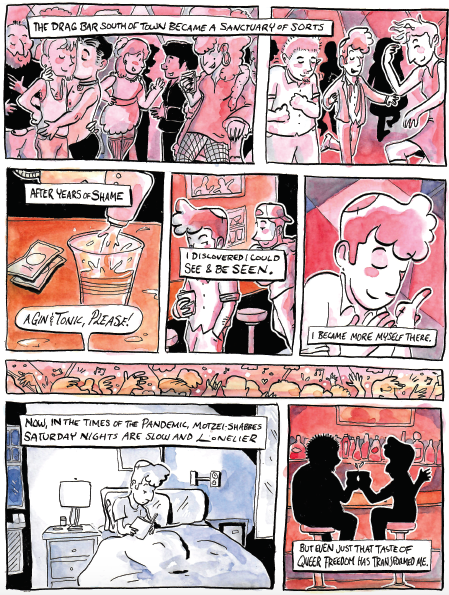

Coming Out While Being Locked In

ABIGAIL FISHER, 19

Throughout this pandemic, I haven’t let myself journal, despite having kept one for most of my life. Instead, I’ve spent the time looking over past journals. Only recently have I begun to understand why. Not writing was the only way to allow myself to grow. It sounds counterintuitive for someone like me who has always used writing to express myself, but by revisiting my journals from the past few years, I’ve been able to see myself more clearly.

I had always expected that the first person I’d come out to would be my journal. In reality, coming out had to happen without it. Over the course of the past two months, I’ve realized, or rather finally allowed myself to admit, that I am a lesbian. It’s all very new, and still sensitive.

In fact, I cringed writing the above sentence just now. I’ve also realized that one of the reasons I was finally able to embrace my sexuality was because I haven’t been journaling. In past journals, I circle around this knowledge about myself, and then ultimately write my way out of it.

Yes, I was an active LGBTQ+ ally, speaking up in classes and on social media throughout high school, and yes, I have a welcoming family. But the social stigma and compulsory heterosexuality that ran rampant in my social spheres made it extremely difficult for me to come out, even to myself.

The spring before senior year, I came out as bisexual, to test the waters. Coming out as queer while leaving open the potential for male romantic partners felt less scary. There was still the possibility that one day I would conform to the norm. I could exist in the world in a way that hid my queerness. Immediately after coming out on Instagram, I was euphoric. I had revealed a part of myself that I had hidden for a long time. And just as quickly, I had a sinking feeling. Had I just lied to the world? Worse still, had I lied consciously?

That July, I wrote in my journal, “When I look into the future and consider a husband, I just don’t feel like I’d be satisfied or even truly happy. But I feel like it would be so much easier to raise kids as a traditional straight family.”

The rest of my entry is a rambling run-on sentence where I twist myself into a pretzel to avoid the inconvenient truth of my identity. I continued, “And I also don’t want to prove my middle school bullies right but it might make everything better if I come out but I’m not even sure that I’m gay but also I’m pretty sure I am and the line between what I want and what I want to want is getting so blurry.” Despite the “ands” and the “buts,” this is the most explicit any of my journals ever got when it came to my sexuality.

Maybe it’s no accident that I journaled in pencil that summer.

While I may not have been aware of it, the choice not to journal during lockdown was a choice to confront the parts of my identity that I’d tried to talk myself out of for so long. Each time I’d gotten up the courage to write about the possibility of being gay, I’d either scribbled it out or explained why it wasn’t true. Not writing gave my internal monologue permission to be free and honest without the gravity that comes with existing in hard copy.

When I came out to my family, I felt the same euphoria I’d felt that spring when I came out as bisexual, only this time it wasn’t accompanied with the dread that I’d told only a partial truth.

While the pandemic has taken so much—lives, livelihoods, hugs—it has provided me the humble gift of stillness. It’s these moments of stasis that allowed me to grow. And when I emerge from this pandemic, I can emerge as my full self.

Abigail Fisher is a Lilith intern and a sophomore at Wesleyan University. She appeared on the Lilith blog in high school.

- No Comments

January 25, 2021 by admin

A Faithful Young Jewish Woman Struggles to Understand Why…

There is nothing quite like being in shul on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. I never feel the impact of the phrase, “k’eesh echad b’lev echad,” that the Jewish people are like one person with one heart, as strongly as I do on the High Holy Days, when everyone is gathered together and wearing emotions openly.

This year, however, because of the pandemic, the world I treasured so deeply was ripped from me. I have a neuromuscular condition which makes me immunocompromised, and I need to be hyper-careful, knowing that even completely healthy people have suffered horribly from this disease. I can’t take any chances of potentially getting the mysterious COVID-19, so for months I knew that I would not be able to go to shul in person for Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur. Even with all of the safety precautions my congregation was taking, I realized I could not risk sitting next to someone who did not wear a mask at all, or did not wear it properly covering her nose and mouth.

Since I am a consistent shul-goer, it was difficult for me to reconcile myself to this. As a child, I sat with my mother rather than going to youth groups. My father took me to shul every Shabbos and Yom Tov. As I’ve gotten older, Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur are especially poignant and meaningful days for me, and I take the seriousness of the teshuva season extremely seriously.

The months of Elul and Tishrei are times of self-reflection. Yet, the beginning of the pandemic was instead a time of fear, anger, sadness, confusion. Of course, I am just a human being. Often, I wondered why Hashem is making this pandemic last so long. I questioned the curveball thrown into our daily, weekly, monthly, and yearly religious traditions, laws, and obligations; making it difficult to accomplish doing the mitzvot. Now, a few months later, I feel I’ve gained perspective.

Some people’s hardships are more evident, while other people have deep, secret hardships about which they do not speak. A human being is not defined by this. What defines a person is how he or she deals with, overcomes, or accepts hardship.

Sometimes we become too complacent, jaded, or ungrateful. When this happens I believe that Hashem sends us a message in order to shake us, wake us up, and show us that we need to do better, whether we need to be kinder and more understanding to ourselves, or to others. While it was painful for me to stay home on Rosh Hashanah and Yom Kippur, I came to realize that I was not meant to be in shul. I stayed home this year so that, hopefully, Im Yirtzah Hashem, if God wills it, I can be there safely next year, and the years to come.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...