Tag : Erika Dreifus

November 5, 2019 by admin

A Woman of Valor Who’s Single

E rika Dreifus is a generous soul on the overlapping writerly and Jewish internet. Her monthly e-newletter, “The Practicing Writer,” and its weekly supplements provide valuable resources for writers. On Fridays, she also publishes a roundup of Jewish literary news in her Machberet (Hebrew for notebook) blog.

rika Dreifus is a generous soul on the overlapping writerly and Jewish internet. Her monthly e-newletter, “The Practicing Writer,” and its weekly supplements provide valuable resources for writers. On Fridays, she also publishes a roundup of Jewish literary news in her Machberet (Hebrew for notebook) blog.

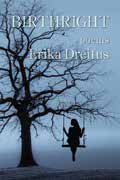

One of the delights of these sources is that Dreifus shares her own writing process, including rejections and successes. Like her 2011 short story collection Quiet Americans, Birthright, her new collection of poetry (Kelsay Books, $17), is one of those successes. These accessible meditations on being a Jewish woman, a Zionist, a critical consumer of social media, and a witness to violence committed and averted reflect a soul dedicated to repairing the world with smarts, spirit, sincerity, and a bit of snark.

With any such gathering of poems, there are those that you move through quickly and those that speak to you with an intensity that causes you to linger and to reread. For me, “A Single Woman of Valor,” a revisioning of Proverbs 31, falls into the latter category. Here—and elsewhere— Dreifus uses Jewish textual traditions to champion the diversity of Jewish women’s lives and to value those who, by choice or circumstance, are not wives and mothers.

Being such a champion of self and others comes “After years of self-doubt, and therapy” and with the sometimes sad recognition that her mortality will represent, as she puts it in the title of another poem, “The End of the Lines.” Yet, in “This Woman’s Prayer,” she clearly and explicitly affirms her own divine self-worth with the words, “Blessed be the One/who made me me.”

Just as Dreifus values her own unique being made in the image of God, so does she employ a midrashic impulse to revalue and reassess those Biblical foremothers who have found themselves on the margin of tradition. In “The Book of Vashti,” Dreifus powerfully gives voice to Esther’s predecessor: “I was cast out/the royal stage cleared for another/whose name would live on in light/while mine receded./ Until now.” And in “The Price of Lilith’s Freedom,” she imagines the namesake of this magazine embracing her “liberation from . . . unequal coupling” and asserting that, despite the “pain, loss, grief,” she would “take that deal again.”

In a series of Israel poems that includes “The O-Word,” “Questions for the Critics,” and “Pharaoh’s Daughter Addresses Linda Sarsour,” Dreifus poetically exposes double standards when it comes to discussing the Occupation, the death drive that seems to animate disproportionate criticism of Israel, and a tweet by a leader of the Women’s March that declared Zionism “creepy.” The awareness in “The Smell of Infection” that social media can sometimes be likened to a tooth needing root canal leads to “Sabbath Rest 2.0,” which entails keeping the “Sabbath free from Facebook and Twitter.”

Birthright ultimately reminds us that we are an amalgam of still-relevant old stories as well as new technologies. Dreifus’ poetry is a worthy read, as is her Twitter feed.

Helene Meyers is the author of Identity Papers: Contemporary Narratives of American Jewishness.

- No Comments

January 28, 2014 by Erika Dreifus

A Not-So-Modest Proposal: Add Another Matriarch to the Mix

“Moses and Jochebed” by Pedro Américo, 1884.

We honor four biblical “matriarchs”: Sarah, Rebecca, Leah and Rachel. And they’re important, even if we recognize them mainly, if not solely, for the sons they birthed.

But they weren’t always admirable. Take Sarah’s treatment of Hagar and Ishmael. Or Rebecca’s devious plan to trick her husband into giving their son Esau’s birthright to their other son, Jacob. True, Jacob got his comeuppance when Leah, disguised as the sister he wanted to wed, married him in Rachel’s place. As for Rachel, it’s hard to know what actions she might have taken, had she survived Benjamin’s birth. We do know that she was susceptible to jealousy.

For these reasons—plus others I’ll list shortly—I propose that we add a fifth matriarch: Jochebed.

I’m not unbiased. “Jochebed” is my Hebrew name (after my mother’s maternal grandmother). As a child, I learned that we (my great-grandmother and I) shared this name with a biblical foremother. But all I knew about the original Jochebed, gleaned from Bible Stories for Jewish Children, was that 1) she was the mother of Moses and his also-impressive siblings, Aaron and Miriam, and 2) she saved Moses’s life by setting him afloat for Pharaoh’s daughter to discover and adopt.

- 2 Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...