Tag : conversion

November 30, 2018 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

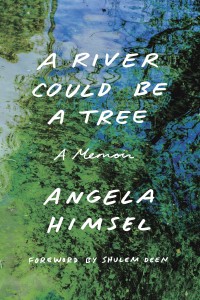

From a Doomsday Church to Judaism

Angela Himsel grew up as one of eleven children in an evangelical family that lived in rural Indiana. The Worldwide Church of God informed her thinking and fulfilled her spiritual needs. Yet she eventually went to Israel, married a Jewish man and is now a practicing Jewish woman. She talks to Lilith Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about her unusual journey.

Angela Himsel grew up as one of eleven children in an evangelical family that lived in rural Indiana. The Worldwide Church of God informed her thinking and fulfilled her spiritual needs. Yet she eventually went to Israel, married a Jewish man and is now a practicing Jewish woman. She talks to Lilith Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about her unusual journey.

YZM: Did you know many Jewish people when you were growing up?

AH: There was one Jewish family in my town. I was acquainted with them and knew they were Jewish but didn’t fully understand what it was to “be Jewish.” They could have been Albanian. Being Jewish didn’t imply anything to me, neither positive nor negative.

- No Comments

January 20, 2015 by admin

A Beit Din Without the Beards

“I have a question,” asked S., my first conversion student, a serious and cerebral college student. “I know we’ve covered the High Holidays, and I understand what they are, and all of that. But the thing about Yom Kippur — how am I supposed to feel?”

No one had ever asked me that before; in fact, I’m not sure anyone ever told me that before. Once asked, it seemed the most obvious question in the world. We talked about it for the better part of an hour, this young man and I, about the shadings between fear and awe, about hope and solemnity. It was the first time that I learned about Judaism from someone on the path to becoming Jewish, though definitely not the last.

I was teaching him because my wife, Rachel — with her packed schedule as small-town rabbi and Hillel advisor — asked me to. How could I prepare someone to become Jewish? Sure, I co-taught our own rural Hebrew school and had worked for Jewish organizations all my life, had lived in Israel for a year, expounding ad infinitum about Jewish history to others on my fellowship. But explaining Judaism — and processing what for so many born-Jews is perpetually unexamined — turned out to be a different matter altogether.

In the two years since that first experience, I have worked with 12 conversion students, teaching in our local coffee shop, our dank synagogue classroom, and in other states (God bless Google, seriously). I love the questions people ask. Why does the Hebrew root of the word for sanctification imply set-apartedness? What do you mean most Jewish law doesn’t come from the Bible? Why is Shabbat 25 hours and not 24? If there’s not a Hell, how does God punish bad people? Sometimes, I don’t know the answers. More often, there isn’t just one answer, and the struggle to accept that exemplifies why converts are so often our best and brightest.

How people have ended up learning with me varies wildly. Those in our community, who maybe know the synagogue but have never been, or who live close enough to have heard of us, might reach out to Rachel, the most public Jew around. Others begin attending services and hear about classes I teach — including Intro to Judaism. A friend two hours away wished aloud that she could learn the laws of kashrut, which led to an entire class series taught online and captured on film. A professor at the local college thinks she might have some hidden Jewish ancestry, and is panting to learn more. A non-Jewish partner was considering conversion before she ever met her Jewish husband-to-be. Shockingly mature college students have decided this is the way they want to bring meaning into their lives. A small congregation in rural Virginia found my YouTube series, the recorded classes I left up after the online series ended. They have no teacher to guide their conversion cohort of five, and want to know: could I do it, maybe? I haven’t said no yet, though my enthusiasm is always tempered with a little bit of dread, and solemnity. Is this the time I’m going to seriously misrepresent Judaism to someone?

What I did not know but should have perhaps guessed is that this work is deeply intimate. I am a happily agnostic observant Conservative Jew, and discussing spirituality and my feelings is not an area of natural comfort for me. Yet zoom in on a recent lesson, one in which my student asks me, “Why does God let bad people go unpunished, at least in the short term?” I start in via Maimonides. “No, “she presses. “I want to know what you think about God.” There’s a long pause before I can even begin to answer.

And there’s more. In part because of my relationship with my students and in part because frankly we are a little hard up for observant Jews here in Maine, I’ve begun sitting on the beit din — the Jewish religious court. I didn’t actually even know that non-rabbis could do this until I moved to sparsely populated Maine, yet here I am. And if I myself automatically assumed that my inclusion in the decision-making body somehow rendered those conversions suspect, might not other people? Might not other institutions in the Jewish world?

But my initial reaction to serving on the beit din, or being asked to — that automatic impulse that surely I couldn’t count — was born out of unfamiliarity and ignorance. As someone who was born Jewish, I’d never really thought about conversion much at all. When I had, I had the mental image you might expect — a couple of older rabbis (male, obviously) looking down severely at a quivering supplicant.

And as we know from recent news stories, the experience can be freighted with gender- and age-related power dynamics, though surely most male rabbis work as hard as possible to keep that from being the case. Yet I’ve been told of conversions in which applicants were told to wait months before mikvah could be scheduled, told they needed to pay a fee, told to wait to be contacted only to continue waiting and waiting.

That’s not the case with those who find Judaism via our little shul. I’ve never seen a beit din that was less than two-thirds female, and the ones I’ve been on are usually entirely female. Though there are moments of solemnity and tears, there is always laughter, and usually at least a little chocolate, as the rabbinical court sits around the same small round table as the convert. I have learned about the kind of joy that is still and calm. There are always, always hugs, which somehow never figured in my imagined scenario with the beards and the fierce scowls and the sitting in judgment.

Nor, I guess, did I imagine the ridiculous tachlis parts of a conversion. I’m not just pointing to the 20 email conversations to book a date, book the mikvah, wait — who’s going to turn it on ahead of time so that the water can warm up? No, I’m pointing to me in the mikvah, pantless and thigh-deep, scooping out a handful of bugs with a paper napkin while cheerfully reassuring the mercifully unaware convert waiting in the bathroom that we were almost ready, just one more minute! This is me, remembering to grab an extra box of tissues as we close the door to the rabbi’s study behind us, ushering a spouse or best friend or child into the room with an encouraging of course you can come in too! Here I am — endlessly bemused, amused, and still a little surprised to find myself one of the guardians of the gates, a coach and a guide to this thing called Judaism.

When people express incredulity that I’m still here, somewhere far away and cold, so unlike the Jewish metropolis I come from, I explain: what a precious thing it is to have someone invite you to stand inside her life with her, to help mold it and alter it.

- No Comments

July 15, 2014 by admin

Hineni: Here I Am

I am 11 years old, in a small stucco chapel on an American army base in southern Germany, attending a Wednesday night songfest of hymns. The pews are wooden, the carpet blue, and the low prayer stools meant for Catholic services are folded in. Because this is a military base that must include everyone stationed here, Jesus can be positioned so that he shows (for the Catholics) or is hidden (for the Protestants). Tonight he does not show.

Outside, it is the Cold War. 1961. A stone wall with barbed wire left over from Hitler’s era circumvents the base, making this a lone outpost in the Alps. Inside, we are singing The Old Rugged Cross, and then Oh, for a Thousand Tongues to Sing, and then Rock of Ages. My music teacher at the Dependents’ School leads us, playing the piano or sometimes the autoharp. From my seat a few rows from the front, I keep looking up to read the wall plaque that lists each hymn’s page.

I’m not here because my parents insist that I come. No, I have walked here alone from our nearby apartment because I love the music, its passionate poetry, and the way that some people close their eyes and look upwards, as if communing with something out there, something I haven’t discovered yet, but can sense in a corner of my heart, a tiny opening to the inexplicable; something that unseals my longing, for what, I don’t know, but it is raw and tender, and expands my small universe in ways I already sense I will never be able to explain to anyone. I love the way the music buoys my life for a while so that my mother’s loneliness in this foreign country and my father’s long absences to prepare for the next war fade into background. I love the peace that fills me on these evenings.

At the end of the songfest, while everyone still stands talking before heading out into the snowy night, I see my friend Alma Elmore take her mother’s hand, and I watch as the two of them prostrate themselves in front of the altar, their foreheads touch- ing the carpet. Mrs. Elmore drapes her arm over her daughter’s back and they lay there for the longest time, praying, I guess, perhaps crying. Their full skirts circle behind them like moments that I sense will travel with me, further and further, concentri- cally, along the trajectory of my life-to-be. No one in the chapel seems to think it’s strange that Alma and her mother lie there, prone, unself-conscious. No one asks them to get up. No one asks if anything is wrong.

With one hand still on my hymnal and the other touching the back of a pew, I stare, embarrassed at first, but also moved by both their liberty and their humility. A tension of opposites holds me. On this army base of stiff uniforms and tattooed forearms, guns in bedroom closets and rucksacks always at the ready, I am not accustomed to seeing women stepping into their own, stepping into something publicly private. Alma and Mrs. Elmore do not move for the longest time, and neither do I, transfixed by something both vulnerable and definitive.

Alma and I never speak of this, not in school and not at our Girl Scout meetings. Her family rotates back to the U.S. in the chess game the government plays with our lives. I will miss my shy, tall friend, the bent of her shoulders, her hair in sausage-like rolls—old-fashioned even then. I will mourn her for a while, but a new girl will come, and we will make room for her because this is what the children of soldiers do.

But this uncensored moment doesn’t rotate or move, doesn’t make room for another. This moment stays with me.

oom for another. This moment stays with me.

And now, decades later, as a converted Jew for the sake of marriage, I often live with that night, far away, in a tiny stitch of the Alps. I think I recognize what Alma’s mother might have felt.

Sometimes, during the Jewish High Holy Days, when I listen to the cantor in her white robe chant the medieval Hineni prayer that translates as “Here I Am”, a wave blows through me and unmasks my life. It opens my heart, though I hadn’t known it was closed, I had no idea. It connects me for a brief moment to everything, to the nub of what it means to be alive, to terror, to joy. And when the cantor prostrates herself in front of the Torah, I feel how close I am to the portal of the unknown, a journey of faith. The stubborn hinges of my life burst open: Here I am.

After my 36-year marriage painfully ended, my heart burst like that. There was no getting away from the fragility that made me feel empathy for every suffering thing. I needed a ritual to help me; the signed papers were not enough. I needed time to be cleaved in two, like a child might need a parent’s blessing before leaving home.

On a raw afternoon, I entered a mikveh, its simple structure adhering to ancient standards for ritual cleansing. In a room with a square four-meter pool of collected rain, uniform through the centuries, I stood naked as the moment of my birth before a mirror, repeating the Hineni prayer as I prepared myself for dunking. Hineni, I said. Here I am.

I was alone, proclaiming my presence, after my husband left me. Hineni. I was in a fractured universe with a song of sorrow on my tongue. Hineni. Without a plan, without a place to live, staring back at my wild eyes in the mirror, my middle-aged belly. I was as present in my life as was humanly possible. Suddenly, in the mirror, naked, the image of Alma and her mother leapt across the decades and cracked my heart wide with the force of humility. Prayers haloed out like ecstatic vibrations erasing self, inscribing open, porous impermanence.

I was back in that army chapel, Alma taking her mother’s hand and the two of them prostrating themselves, reaching for me, keeping me company. I understood as never before how aloneness meets mystery. Bombs could drop, the Soviets could attack at any moment, we could all be killed; release was the only path to transformation, no matter what religion, what creed.

I walked down the tiled steps and lowered myself into the warm living waters, dunking under once, then praying, dunking again, then again, like some primordial creature dying and being reborn at the same time. Let the waters take you, the female rabbi had said. Let the old float away, the new come towards you. As she spoke, I began to experience the water itself as prayer. As hope.

No one in the chapel thinks it’s strange that Alma and her mother lie there, prone, unselfconscious, I remembered. No one asks them to get up. No one asks if anything is wrong.

I felt alive.

Hineni.

Here I am.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...