Tag : children’s books

January 26, 2021 by Sarah M. Seltzer

Meeting Challenges: 4 New Books for Young Readers

Beep Beep Bubbie by Bonnie Sherr Klein, illustrated by Élisabeth Eudes-Pascal (Tradewind Books, $19.95) Planning to go shopping together for apples for Rosh Hashana, two grandchildren are concerned when their grandmother surprises them with her motorized scooter. She shows them all the things it enables her to do, and how they can continue to have fun with her.

I Am the Storm by Jane Yolen and Heidi E. Y. Stemple, illustrated by Kristen Howdeshell and Kevin Howdeshell (Penguin $17.99). Extreme weather, hurricanes, forest fires, blizzards can be frightening. But people too, can be powerful, can prepare and protect themselves. A child narrator notices it all, and can be powerful in being resilient too.

I Talk Like a River by Jordan Scott, illustrated by Sydney Smith (Neal Porter, $18.99) “I wake up each morning with the sounds of words all around me. And I can’t say them all.” This lyrical book about speech difficulty is narrated by a boy whose caring father takes him to a favorite place by a river. We learn in the author’s note that his own father did this for him when he had “bad speech days” as a child.

The Talk: Conversations about Race, Love & Truth, edited by Wade Hudson and Cheryl Willis Hudson (Crown, $16.99). This often heartbreaking but hopeful anthology shares difficult conversations parents have with their children to keep them safe in threatening everyday situations. “Moving through life as a responsible member of society requires an intense alertness,” writes one of the many talented kidlit author contributors, Min Le, a Vietnamese American, who addresses his young children: “I am Buddhist, and your mom is Jewish. While we will always rejoice in this blending of faiths, spirituality can feel tenuous when the headlines are riddled with attacks on places of worship.”

- No Comments

July 27, 2020 by admin

A Children’s Classic with a Very Relevant Chapter

I don’t know why I never read books by Sydney Taylor when I was growing up (it wasn’t my gender; my sisters never did, either). But when my wife pulled her old copies out of a box recently, and my six-year-old daughter enjoyed listening to the first one, I was thrilled.

As a scholar of modern Jewish literature, and having designed and directed a residential program for authors of Jewish children’s literature, I had been a little embarrassed to admit that I know the All-of-a-Kind Family by reputation only. Getting to know Ella, Charlotte, Hennie, Sarah, and Gertie (and their little brother, Charlie) by reading Taylor’s books aloud to my daughter has been an unmitigated pleasure.

But imagine my surprise when, a few weeks into total Covid-19 isolation, as I read to my narrative-obsessed daughter for more hours each day than I had ever imagined possible, we unexpectedly came to the chapter in the second book in Taylor’s series, More All-of-a-Kind Family, “Epidemic in the City.”

I had been seeing historians posting primary sources on Twitter and looking to the 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic as a newly relevant moment. But that’s not the epidemic the sisters encounter in Taylor’s book. Instead, it’s an epidemic of “infantile paralysis,” which only after a quick Google did I learn was the first major outbreak of polio in the U.S., which in 1916 ravaged the Lower East Side and Brooklyn neighborhoods where so many Jewish kids, like those in Taylor’s books, were concentrated. “The newspapers printed it in bold black headlines: Epidemic!”

Taylor is, as usual, spare and efficient in describing the plague’s effects: “Soon there were empty seats in the classrooms, and the clang of the ambulance bell was heard more and more frequently.” Apparently Japanese camphor was thought to ward off the disease (“Don’t like the funny smell,” Charlie says).

The family soon decamps to Rockaway Beach—their first-ever seaside vacation, made necessary (despite how little money they have) to avoid the disease in the crowded city. The children don’t get sick, but Lena, the woman marrying their Uncle Hyman, does, and eventually they have to convince her that even though she has lost her leg to the disease, Hyman still loves her and wants to marry her.

The same day I read those chapters to my daughter, I was spending my spare moments searching AirBnb and asking for recommendations on Facebook, trying to find a Rockaway Beach of our own (though in our moment, when public beaches seem unlikely to be useable, what I was hoping to find was a lake house with a little stretch of sand or dock). And every day we were hearing from friends and relatives who, like Lena, had caught the disease and ended up in the hospital.

In an excellent article about Taylor and her books, the literary scholar June Cummins—who tragically passed away last year, before publishing the biography of Taylor she had been working on—noted that Taylor “always claimed that she wrote the All-of-a-Kind Family stories for her daughter Jo, who asked, ‘Mommy, why is it every time I read a book about children, it is always a Christian child? Why isn’t there a book about a Jewish child?’”

What’s fascinating is that for my daughter, who has always had plenty of books about Jewish kids to choose from, the mirror that Taylor has given her, in the midst of a strange and upsetting situation, wasn’t of a Jewish child, per se, but of children living, bravely, through an epidemic.

—

Josh Lambert is the Sophia Moses Robison Associate Professor of Jewish Studies and English at Wellesley College and until recently the Academic Director of the Yiddish Book Center.

- No Comments

July 27, 2020 by admin

…And for Middle-Schoolers and Young Adults

I’ve been reading middle grade and young adult books, mostly novels. They all end on bittersweet, complicated but hopeful notes. Which feels right at a time like this—and probably always.

The Blackbird Girls by Anne Blankman (Viking, $16.99)

A novel about two eleven-year-old classmates in 1986 Chernobyl. One from a Jewish family whose estranged grandmother is a Holocaust survivor, and the other from a family that harbors anti-Semitic prejudices common to that time and place; this family sees violent physical punishment as ordinary and acceptable childrearing. The two girls, despite the initial passionate antipathy between them, end up escaping together from the radiation explosion that turned their world upside down. All this, in a regime that prioritized spinning the news over protecting the safety and health of its citizens.

Someday We Will Fly by Rachel DeWoskin (Viking, $17.99)

This coming-of-age young adult novel is narrated by a teenage girl from a family of circus performers. After her mother has disappeared, she escapes from Nazi-occupied Warsaw with her dad and a developmentally delayed baby sister to Japanese-occupied Shanghai. Daringly resourcefully, she makes valiant efforts to take care of herself and her family, sporadically attends school, makes friends with a Chinese boy and finds work as a performer at a “gentleman’s club” without her father’s knowledge.

Yes No Maybe So by Becky Albertalli & Aisha Saeed (Balzer & Bray, $19.99)

A put-upon, awkward, 17-year-old older brother—who dreads this—will have to make a speech at his sister’s bat mitzvah. The narrative, set in contemporary Atlanta, pairs him with a Ramadan-fasting girl he knew as a toddler; they both semi-willingly become volunteer canvassers for a Democratic candidate for state senate, in a campaign rife with anti-Semitism and anti-Muslim tropes. There’s a sweet and tentative romance here, too.

Gravity: A Novel by Sarah Deming (Random House, $20.99)

Half Dominican and half Jewish, Gravity Delgado is a young female boxer with a big heart and lots of smarts, growing up in a broken home in contemporary Brownsville, Brooklyn. She is literally a fighter, and her grit is inspiring as she finds her way to a Cops ’n Kids gym and eventual Olympic ambitions. I am so not into literal fighting—metaphorical, yes—that I was surprised how much I became absorbed in this YA novel.

White Bird: A Wonder Story by R. J. Palacio (Random House, $24.99)

In Palacio’s bestselling middle-grade novel, Wonder, about a boy with a disfigured face who begins to attend school for the first time, one of the characters, Julian, eventually comes to regret his initially bullying behavior. In Palacio’s new book—this time a graphic novel— Julian, in fulfillment of a school assignment, corresponds with his grandmother, who survived as a Jewish girl in hiding in France during World War II. It turns out her life was saved by a boy who had polio and had been bullied and ostracized by everyone in their class.

The Long Ride by Marina Budhos (Wendy Lamb, $16.99)

In the early 1970s in Queens, New York, three close friends—mixed-race girls who always felt like outsiders at their local, mostly white elementary school—learn that they will be bussed to junior high school as part of an experiment to racially integrate the schools. As we find out in this middle-grade novel, the results are complicated…

Free Lunch by Rex Ogle (Norton Young Readers, $16.95)

A timely memoir tells of living in poverty in America. A boy is growing up with his mom and her boyfriend, both of them out of work and depending on food stamps and pawn shops. In an environment occasionally punctuated with violence, the boy learns to navigate middle school, where he struggles to find inventive ways every day to avoid having to shout out to the lunch lady that he gets the free lunch.

Naomi Danis

- No Comments

July 9, 2019 by admin

Lilith Talks to Erica Perl about Lifting the Suicide Taboo

When All Three Stooges (Knopf, $22.99) first came across my desk, I saw glancing through it (spoiler here) that in it a dad named Gil dies by suicide. I have to admit I avoided it, because my husband, also named Gil, had died that way. After meeting you when the book won a National Jewish Book Award, I bought a copy for you to sign, and found it a thoroughly engaging and rewarding read.

In light of my own experience, I really appreciated that your middle-grade novel doesn’t presume to speak for—or to—the child whose dad died by suicide, but rather to the friends of that child; that is, to a broader audience of the many who are often deeply affected by such a tragedy. There are doubtless many young readers who experience suicide by a degree or two of separation or, for that matter, other tragedies, and who need to feel seen and have their stories told. Can you share something about your journey preparing to write All Three Stooges?

Over the years, some of the things that have happened in my life have lodged themselves in my head and heart. When I write, it sometimes shakes them loose and I’m surprised to see them on the page. Early on in my work on the book that would become All Three Stooges, I started thinking about the suicide death of a friend who was also the father of my child’s best friend. I wanted to focus on the ripple effect of a suicide through the lens of a friendship between two boys. To prepare to write the book, I did a lot of research. I read books about suicide, grief, and loss. I interviewed teens who had lost parents to suicide. And I volunteered at a grief camp to better understand the diversity of ways kids grieve.

Over the years, some of the things that have happened in my life have lodged themselves in my head and heart. When I write, it sometimes shakes them loose and I’m surprised to see them on the page. Early on in my work on the book that would become All Three Stooges, I started thinking about the suicide death of a friend who was also the father of my child’s best friend. I wanted to focus on the ripple effect of a suicide through the lens of a friendship between two boys. To prepare to write the book, I did a lot of research. I read books about suicide, grief, and loss. I interviewed teens who had lost parents to suicide. And I volunteered at a grief camp to better understand the diversity of ways kids grieve.

As a reader, I felt so much affection for your narrator, Noah—who perhaps was an example of the “boys who don’t talk” trope. He is always impressed and annoyed with Noa, his homonymic female classmate who runs rings around him in articulateness and sophistication. The families in this story are diverse, just as they are in the real world, in a way we don’t always see in kids’ books: one has divorced parents, one is an interfaith family with two moms, one with a deceased parent and step-parent. How did gender play into your considerations of all these characters?

I started with Noah and Dash, because I knew I wanted to show how strong—and yet how fragile—boys’ friendships can be. Noah’s nemesis, Noa, came next. She’s a girl who’s comfortable doing all the things Noah finds challenging (like: saying the right thing, being patient, and being a good friend to someone who is grieving). And the parental characters fell into place very naturally for lots of reasons. For example, I knew very early on that Noah would be raised by strong women (his two moms and older sister). It has been incredibly gratifying to hear from families who feel seen because of the diversity of Jewish and interfaith families in All Three Stooges.

I’m full of admiration for how you so effectively combined the characters’ love of comedy and humor with such a difficult topic. How did you dare, or rather, how did you know to do this?

Thanks—that means a lot to me! I’ll be honest, it was a bit of a tricky dance. Noah and Dash love comedy, and so does Gil. But, unbeknownst to Noah, Gil struggles with depression—which is something he has in common with many comedians. I tried to use humor to show how laughter can connect and sustain us, and I sought comedy examples to amplify this message as well. I sought to explore the line between sadness and laughter, while making it very clear that there’s nothing funny about the devastating impact of severe depression and suicide.

Many consider suicide a taboo subject. In your essay on Slate, “Alone in the Dark: Why we need more children’s books on suicide and severe depression,” which appeared following some notable celebrity suicides, you wrote “My husband and I didn’t want to explain to our kids why their friend’s dad, the guy who’d made them s’mores on camping trips, was suddenly gone,” and you also survey other books for young readers that touch on this subject that is so often avoided—even by adults. How has this novel been received?

I was extremely honored that All Three Stooges won the 2018 National Jewish Book Award for Children’s Literature and a 2019 Sydney Taylor Award Honor. So, in that respect, the novel has been wonderfully received and celebrated. My only concern is that some people do view suicide as a taboo subject or feel ill-equipped to handle conversations about it. This kind of thinking is counterproductive: talking and reading about mental illness doesn’t produce it. Rather, it destigmatizes mental illness, promotes understanding, and invites those who are struggling to seek treatment and support. Furthermore, All Three Stooges is a book about being a kind, empathetic, and patient friend when someone you love is grieving. It is a book for all children ages 10 and up.

Aside from home and family, this story takes place in a realistic-feeling and upbeat Reform synagogue and Hebrew school setting, with warm, wise rabbis and teachers. Learning that our behavior has consequences is an important part of growing up, and hopefully very much more the point of the bar/bat mitzvah experience than an elaborate party.

Conveying this lesson is taken so seriously here and (another spoiler) that a bar mitzvah celebration could be postponed—not for any reason one might have expected—made so much sense. It also felt like an echo of the suicide theme, where behavior has consequences that can’t just be wished away. There was something so true about how everything was not alright—Noah in his own funk, and frustrated at his bereaved friend’s avoiding him, messes up and behaves unfairly towards him—and yet, life goes on, with all its ups and downs, and continues to be good in surprising ways. How were you able to map out such a very humanly complicated story?

As I was plotting this novel, I felt very sorry for Noah, because, though he makes some poor choices, his heart is clearly in the right place. So, I was very tempted to end the book differently, and give him the results he wants: having all his misdeeds forgiven and becoming a bar mitzvah as scheduled. But the more I tried to write that ending, the more it felt wrong. Deciding not to give Noah the result he craved allowed me to take him down a path that was more honest and, because of that, ultimately hopeful. Writing Noah’s journey this way also allowed him to discover something that I believe: even in times of profound loss, love and laughter endure.

- No Comments

April 15, 2019 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

From “I Hate Everyone” to “While Grandpa Naps,” Naomi Danis on Her Fiction for Young Readers

Naomi Danis is Lilith’s resident angel/soother of souls/bridge over troubled waters. She combines a practical-get-it-done attitude with an uncommon amount of kindness and empathy and she is much-loved within the office and beyond.

Danis is also an accomplished author of several well-received picture books and as she prepares to launch her latest, While Grandpa Naps, illustrated by Junghwa Park, she talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about the way she keeps so many balls spinning in the air with such effortless grace.

Danis is also an accomplished author of several well-received picture books and as she prepares to launch her latest, While Grandpa Naps, illustrated by Junghwa Park, she talks to Fiction Editor Yona Zeldis McDonough about the way she keeps so many balls spinning in the air with such effortless grace.

YZM: Tell us when you started working at Lilith and a little bit about what the job has been like.

ND: I started working at Lilith in 1988, after nine years at home raising three children, during which time I began seriously writing for kids. I had trained as an early childhood teacher, also have an MA in English, but learned from a friend at my Forest Hills synagogue who did grant writing that Lilith was looking for someone. The position turned out to be administrator, and I really wanted to be called something like assistant editor, but two friends in publishing I consulted said if you like the people, take the job. I still love it after all these years, and feel very lucky and grateful every day. I have the kindest, smartest, funniest, most caring, talented, inspiring and encouraging colleagues.

- No Comments

January 10, 2019 by admin

Revisiting My Past With All-of-a-Kind Family Hannukah

Several decades have passed since I encountered an All-of-a-Kind Family book for the first time. The newest installment looks different (as do I), but our reunion was sweet.

All-of-a-Kind Family Hanukkah (Schwartz & Wade, $17.99) follows the youngest sister of five, Gertie as she tries to help her sisters make latkes. The book is unlike Sydney Taylor’s original series in striking ways: author Emily Jenkins uses the present tense to convey a young child’s sense of immediacy, and Paul O. Zelinsky’s bold and tender color illustrations look nothing like Helen John’s original detailed ink drawings. Still, the characters were immediately recognizable, and the book retains the series’ essential New York-yness. Reading it, I was filled with the cozy longing the series has always triggered in me.

As an eight-year-old All-of-a-Kind Family fan, I didn’t understand my nostalgia for something I’d never known. I wanted to live in Taylor’s world, with its sisterly camaraderie and muslin petticoats. I thought my desire to buy candied tangerines from a peddler on the Lower East Side made me uniquely soulful. But my reactions actually reflected the feelings of many contemporary American Jews. As the late children’s literature expert (and Taylor biographer) June Cummins noted in a 2003 article: “In her book Lower East Side Memories, historian Hasia Diner develops the argument that this small geographical area became a source of cultural identity and pride for American Jews after World War II. … Diner credits Taylor as the first writer to view the Lower East Side nostalgically, effectively recreating it for postwar American Jews and non-Jews.”

Aha!

But I was also a kid, and kids have different relationships to their favorite books than adults do. Nothing I read today could ever capture my imagination the way the books I loved as a child did. That’s the consuming magic of childhood, the endless fascination we have with our favorite things. So, no literary feast can match the All-of-a-Kind Family episode in which Charlotte and Gertie amass a hoard of chocolate babies and broken cookies, then devour them in their bed after lights-out.

As an adult, it’s hard to find the room, or time, to enjoy this kind of extended imaginative experience. That’s probably just as well, since the idea of buying huge quantities of sweets for only two cents (the enduring fantasy of my childhood, and one that is slyly referenced in All-of-a-Kind Family Hanukkah) doesn’t have quite the same appeal today. Alas.

But maybe my most enduring All-of-a-Kind Family memories are yet to come. The scholar Alexandra Dunietz, who recently completed Cummins’ biography of Taylor, told me, “When my oldest was seven or eight, I started to read the books to my children. I remember this tremendous happiness we all felt—‘Oh, this is about a Jewish family, and they’re doing normal things! They’re losing library books! They go to the library on Friday!’” (We went to the library on Fridays, too.)

“I think I read all five books one after the other, a chapter or two a night,” Dunietz adds. “I have two boys and two girls, and they were all engaged.”

My three-year-old is too young for All-of-a-Kind Family Hanukkah, but he does love books about New York City. So I’ll show him the pictures of Gertie and her sisters in the hopes that he, too, will one day be captivated by the adventures of his fellow New Yorkers, the All-of-a-Kind Family.

Elizabeth Michaelson Monaghan is a former Lilith intern and native New Yorker. Her work has appeared in City Limits, Paste, and McSweeney’s Internet Tendency.

- No Comments

October 16, 2018 by admin

A Canadian Feminist Publisher Known for Kids’ Holocaust Books

Who would have thought that children’s books about the Holocaust would become popular with kids?

Who would have thought that children’s books about the Holocaust would become popular with kids?

The Holocaust Remembrance Series for Young Readers, from Second Story Press in Toronto, now has more than two million copies in print and is available in 51 countries and 39 languages. Though the series started with only one such book, publisher Margie Wolfe never doubted the value and importance of “having that literature available to children as they were growing up. The challenge was to take a difficult or problematic subject and make it work for kids. And that’s what we figured out.”

But even Wolfe was surprised at what followed.

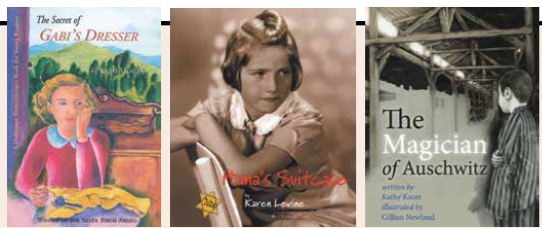

“We always assumed the first one would be a one-o ,” she says. The Secret of Gabi’s Dresser, intended for 9- to 12-year olds, was published 20 years ago. “It’s based on the true story of a child, the author’s mother, in Czechoslovakia. When the Nazis came to collect Jewish girls, she was hidden in a dining room dresser and was saved.” Wolfe recalls, “My sales reps, who are commercial sales reps, thought they’d humor me. ‘Oh, Margie wants to do this, we’ll sell it to a few Jewish bookstores and that will be the end of it’.” But it was only the beginning.

Gabi started garnering kudos, including the Ontario Library Association’s Silver Birch Award. “That was an important moment for us,” explains Wolfe. “There’s a short list chosen by librarians, and then the kids vote. The kids had an opportunity to decide on something fun and easy, but they didn’t. They chose this true story about a child in war whom they could empathize with and cheer for and su er with.”

The author of Gabi, Kathy Kacer, wrote more award-winning books for the series. And then, said Margie, “there was our ‘miracle book’: Hana’s Suitcase,” published in 2002. This is a true story about a woman who travelled from Japan to Canada to meet the brother of a child killed in the Holocaust. Hana’s Suitcase is Canada’s most honored children’s book, ever. It has been translated into dozens of languages, and is still popular and still winning awards around the world.

But what is most important to Wolfe is that “it revolutionized what it was possible to tell kids at a young age.

“I always knew that you could. I just didn’t know how to do it. And then I realized that what we had to do was to tell a story. With Hana, we are telling a mystery, an adventure story.” Years ago, she says, someone from Yad Vashem, Israel’s official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust, approached her, saying, “We do Holocaust books for children. How come yours are more successful?” Her response: “They publish research. We publish stories. The challenge with each one is to create the most compelling narrative without sacrificing content.”

The problem presented by this kind of writing for children was taken up recently by Ruth Franklin in The New Yorker, in “How Should Children’s Books Deal with the Holocaust?”

“Most children today will never see a survivor’s tattooed arm,” wrote Franklin. “Those of us who did are likely trying to figure out how to approach the Holocaust with our own children, wanting them to recognize its significance in their family history without allowing that knowledge to burden or define them. Still, to me, there’s something essential about the interactions among generations in the stories we tell about the Holocaust.”

The most risky title in the Second Story Press series, Wolfe acknowledges, is The Magician of Auschwitz, also by Kathy Kacer. “I knew with the title that we were taking a huge chance,” says Wolfe. “But it also won the [Silver Birch] children’s choice award. When kids 8 to 12 were given a selection of books to read,” she says with a degree of wonderment, “they voted for a book called The Magician of Auschwitz.”

Second Story Press has become a magnet for writers from all over the world who want to submit Holocaust books for children. Wolfe is very clear about what she will publish. For example, she flatly rejects pitches where the characters are rep- resented by animals.

“We won’t do them,” she insists. “We want kids to know these are real stories, not some fantasy about animals, that the ones who suffered were people.”

And because the books are translated into German and Eastern European languages, she makes sure there’s nothing in them to make “kids in those countries feel responsible for what happened decades and decades ago. We don’t say German soldiers. We say Nazis.” She explains: “We want the readership to be mostly non-Jewish, and 95 per cent are not Jewish. That’s the goal—to have those children read the books and to know that his- tory, to say how awful, but not to feel responsible for that history.”

That history is also Margie Wolfe’s history. She was born to survivors in the displaced persons camp at Bergen-Belsen, and came to Toronto as a very young child. Her rst job was with The Women’s Press in Toronto, and she’s proud of being a feminist publisher for the last 40 years.

She founded Second Story—the official name is Second Story Feminist Press—with three other women; she later bought them out.

“Anything I do is informed by feminism,” she explains. “It’s what I bring to whatever kind of book that we do.” Her list includes fiction, nonfiction and biography for children and adults. A book she describes as “Thelma and Louise but better, about two women with mild Alzheimer’s” who find an offbeat way to maintain their independence, won Canada’s prestigious Leacock award for humor.

And then there’s a Gutsy Girl Series, and I’m A Great Little Kid picture book series for ages 5 to 8, a mystery series for teens, a First Nations Series for Young Readers, focusing on indigenous peoples in North America, which has garnered many awards and is popular in U.S. school libraries, and even a children’s book about euthanasia. New releases this year include Black Women Who Dared, for children 9 to 13, The Story of My Face, about a girl scarred by a grizzly bear attack, recommended for ages 13 to 17, and a novel for adults about two Winnipeg sisters haunted by their childhood in Russia.

But for all the eclecticism in the lineup, Second Story sticks to its mandate to publish books by Canadian authors that pro- mote feminism, social justice and Judaica.

“We did the first collection of Yiddish women writers in translation back in 1995,” Wolfe notes.

Perhaps most amazing—and testimony to Margie Wolfe’s shrewdness as a publisher—is that, even with her strict mandate, Second Story Press manages to turn a small pro t, albeit with some government grants, available to all Canadian publishers who meet certain criteria. “We have been a pro table company for 20 years,” she says. “Our biggest level of sales was last year and this year will likely be even bigger. I think that has some- thing to do with what’s going on in the world today. When we rst started in 1980, nobody even thought we would last very long. We were on the periphery of real publishing in Canada. Now, there’s no question, and hasn’t been for a long time, about our validity. We operate on a world stage. Some of the largest publishers in the world buy from us: Random House in the U.S., Ravensburg in Germany.”

Wolfe, who is in her late 6os, allows herself one last brag: “Arguably we are the best in the world at doing these books for young children. I’m proud of the quality of the books and the reach they have and the possible impact they have. I like to think that a kid who is caught up in one of the stories will have that in their head for a long time and take it with them and help them know how to behave the next time they have a choice to make that is less or more humane. And that is the main reason we want the readership to be not just Jewish kids.”

In effect, the mandate and output of Second Story Press is Wolfe’s own raison d’être. “It’s my activism,” she says. “I spent my time like everybody else at millions of demonstrations and this is what I have to contribute, as a woman, a feminist, even as a Jew. This is my contribution and my legacy.”

JUDY GERSTEL is a Toronto-based freelance journalist, formerly a critic and editor at the Detroit Free Press and Toronto Star.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...