Tag : Carol Dine

January 20, 2015 by admin

Strange Comfort

One day, a week after my second chemo treatment for my fourth bout with cancer, I was feeling all right and decided to take the T to Newbury Street in Boston to see an exhibit of paintings by the renowned artist Samuel Bak, who survived the Holocaust. I was bald and wore a black turban.

That afternoon, I stood in front of “Da Capo” at the Pucker Gallery, a painting of shepherds sitting next to a pyre of violins, facing away from one another, hands raised, pretending to play music with their wooden staffs. The head of one shepherd had been shaved. All I could feel was my cold, bald head beneath my turban, and, thinking I might faint, I rushed home. The next day, I started to write about this painting: “…the mourners play on/past shloshim/past shneim asar chodesh….” [Quartet]*.

As my treatments continued, I visited the gallery as often as I could, and I kept writing — feeling ill, feeling terrified of death, but also experiencing this art as the thing that was getting me through. It was strange comfort, a ritual of call and response.

When I was too weak to leave the house, I asked Mari, the gallery assistant, to send me images of the paintings and drawings that had especially moved me. I focused my imagination on one image at a time.

I had no plans — no idea that these poems might become a book. I was simply grateful to be writing. At first I thought that I might write just a few poems inspired by Bak’s art, but I couldn’t stop. When I had three poems that I considered polished — that had been vetted by my writing group — I emailed them off to Mari as a gesture of thanks, because she had taken me behind the scenes to view Bak’s work on the second floor.

Without telling me, she forwarded the poems to Sam Bak, and within the week, he wrote to me: “I am greatly moved by your words on my art. To know that it can bring what you describe. It is more than I could dare to hope for.” My previous book, Van Gogh in Poems, was written as if in the voice of a painter who was long dead. I’d also written poems about the work of Frida Kahlo and Mary Cassatt — but Bak was a living artist, who, at 80, was still painting. Hearing his positive response affirmed what I was creating and made me feel less alone. While writing, I was aware that I might die. This realization propelled me and made the work urgent.

The images that I chose to write about actually chose me. With some, the objects pulled me in: a chess piece, an oversized pear, a broken easel. The poems would expand, grow into being as I wrote them.

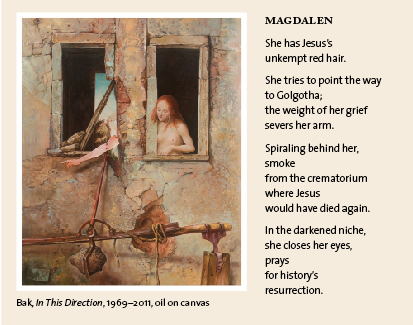

With other paintings, such as “In This Direction,” I knew where the poem might lead. I “knew” that the naked, red-headed woman was Magdalen. What drew me to the figure was the shock of her severed arm. My body, my breasts felt similarly severed. When I looked closer at the background, I saw smoke rising from the crematorium and, given that Jesus was a Jew, I penned the line, “Where Jesus/ would have died again.”

The severed arm also reminded me of my father’s soul-killing emotional abuse which accompanied me throughout my childhood and on into my adult life. I still need to remind myself every day that I am smart, worthy. As a secular Jew, I rarely go to synagogue, but I spend every Yom Kippur alone at home, reading aloud from my father’s prayer book. Some years ago at temple I noticed a printed sheet on one of the seats and I took it with me. “Know whom you put to shame,” it says, “for in the likeness of God is she made.” If only there had been such a message when I was growing up, perhaps I might have told someone what I had to endure.

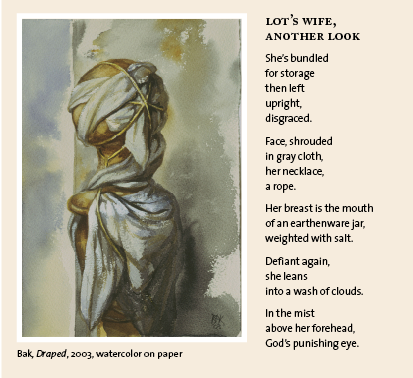

What drew me to “Draped” was the figure bundled in cloth and tied with ropes. I saw the chess piece — a pawn — as female. I felt her powerlessness, her imposed silence. At first I didn’t know who this figure was, but then I remembered Lot’s wife, who was nameless — another indignity — and centered the poem around her.

Here, I explore the terrible price of defiance. “She’s bundled/ for storage/ then left/ upright,/ disgraced.” Of course this painting triggered memories of my childhood, too. If I spoke out or argued with my father, I was subjected to his rage and humiliation. He was a physician, and he knew just how to hit me without killing me. As I was writing the poem’s final line, I heard in my subconscious “my father’s fist,” but instead I wrote, “God’s punishing eye.”

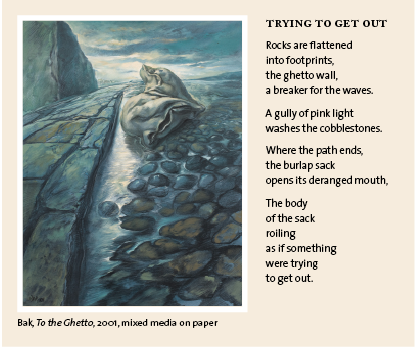

I came to recognize Sam’s recurrent symbols and what they meant. The chess pieces — because after the Holocaust, Sam’s stepfather played game after game with him. The sacks — because his father put him in a sack when he was nine and smuggled him out of the labor camp in the Vilnius Ghetto; his father and all his grandparents were murdered immediately afterwards.

Pillowcases — because the Nazis allowed him to take one thing from his house, and, though he wanted to take his teddy bear, he didn’t want to seem like a baby. So he took his pillow, but it got heavier and heavier as the Jews were marched down the street in the pouring rain, and so he dropped it. The pears — because, as Sam says, smiling, “I much prefer them to apples.” With all he has had to overcome, he has maintained a sense of humor!

Over the next 11 months, I sent Sam poems, one by one. The work began to feel collaborative. “Your poems are like echoes that return to me, and their volume feels stronger than the sound of their origin,” he wrote back.

Sometimes a poem inspired a new painting. “Your poem reads so profoundly into the myth of the painting’s image that I have decided to dedicate it to a much larger size.” He respected my vision, and never censored me. He treated me as an equal, although I would have been threatened if I’d actually known how famous he was. Still, I didn’t think about him when I wrote. The work was everything.

One evening at dinner at his and his wife Josee’s home, I decided to tell them my secret: that my long blonde hair was a wig, and that I was undergoing chemo. I’d written about my experiences with breast cancer in my memoir, Places in the Bone, and I gave them a copy. The parallels of suffering were now out on the table, and that seemed so imbalanced to me. Holocaust and cancer…? But they were very appreciative of my courage, of what I was going through and had gone through, and that added another layer of depth to Sam’s and my relationship.

I admit to feeling guilty during the whole time I was writing these poems. No one in my family had been brutalized by the Holocaust; they died of natural causes. My paternal grandparents, immigrants from Lithuania, whose original name was Daen, came to America, assimilated, and didn’t even give my father a bar mitzvah.

At the same time, I felt worthy because Sam praised my descriptions of his images of grief. That gave me permission. I knew, from reading Painted in Words, his autobiography, that Sam and his mother had endured hell, and that gave me strength. To survive, Sam used art, and although our struggles were radically different, so did I.

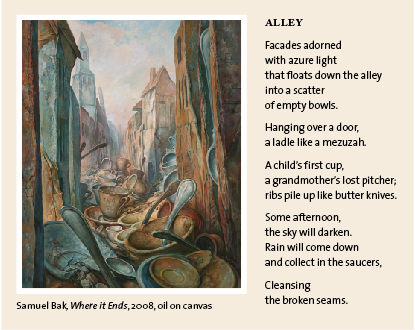

Bak’s genius — expressing the beauty that exists in horror, the hope that lives amid destruction—speaks to me. Above the ruined ghetto, he paints an azure sky or floating white clouds. Images fill with cerulean, orange, sun-yellow, gold, red.

For the cover of Orange Night I chose a bird. At first glance, the bird is pure white, a dove suspended in a tree, surrounded by a peaceful, misted sky. But look closer and the bird is fragile, made of paper, its wing a tallit, or the Israeli flag. And the tree branches end in talons.

In February 2012, Sam wrote, “Please keep overwhelming me with your inspired poetry. In the future I can see a whole book dedicated to the fertile encounter of our mutual visions.” And so our book happened. I dedicated it to my dear friend Tehila Lieberman, who assisted me with the Jewish content. And to a very caring man, Dr. Steven Come, my oncologist.

I held my first copy of Orange Night in the Pucker Gallery, sitting beside a friend on a low wooden bench. We turned page after glossy page. I thought, “I survived for this.” She asked if I wanted to read aloud.

But I couldn’t even whisper.

[*past the thirtieth day of mourning, past the twelfth month.]

Orange Night (Pucker Art Publications, 2014), is Carol Dine’s fourth published collection of poetry. Her memoir, Places in the Bone (Rutgers U. Press, 2005), discusses the redemptive power of art. She is currently working on Resistance, poems in the voices of women who have resisted war, terror or abuse. She teaches at Massachusetts College of Art and Design.

See more of Samuel Bak’s art at the Pucker Gallery website.

- 2 Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...