Tag : Anita Hill

June 20, 2018 by Sarah M. Seltzer

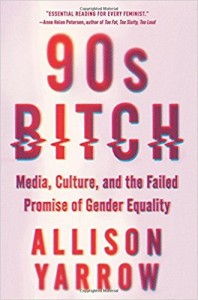

The Bitches of the 1990s Weren’t Villains After All

“Jews are really good at knowing our history,” says Allison Yarrow, author of the new book 90s Bitch, which casts a critical eye on the gender politics of the Clinton years, from Monica Lewinsky to Marcia Clark, examining how the rise of the 24/7 media landscape turned them into villains, pushing sexism and silencing into the air we breathe today.

“Jews are really good at knowing our history,” says Allison Yarrow, author of the new book 90s Bitch, which casts a critical eye on the gender politics of the Clinton years, from Monica Lewinsky to Marcia Clark, examining how the rise of the 24/7 media landscape turned them into villains, pushing sexism and silencing into the air we breathe today.

“We need to know the real history of what happened in the 1990,” Yarrow told Lilith, during a chat that covered Bill Clinton’s non-apology, the limits of nostalgia, the Sex and the City anniversary and of course, the word “bitch.”

- No Comments

April 12, 2018 by admin

My Summer in Hollywood

“Truth even unto its innermost parts.”

—BRANDEIS UNIVERSITY MOTTO

I was a student at Brandeis University when Anita Hill gave her groundbreaking testimony to the Senate Judiciary Committee in the fall of 1991. This single courageous act sparked a national decades-long conversation on sexual harassment in the workplace, a conversation which, with allegations of abusive behavior by Harvey Weinstein and now countless others, has exploded in a seemingly end-less stream of #MeToo narratives.

Me, too.

My original career ambition was film-making. While at Brandeis, I started a film club on campus. I collected signatures, petitioning the administration to establish a film studies program. As the student liaison, I met with the provost, who shared a similar vision. He put the wheels in motion, and he also contacted a Brandeis alumnus, a director in Hollywood, who offered me an intern-ship for the summer as his assistant. I was over the moon!

Once in Los Angeles, though, I felt like an East Coast fish out of water. At 20, I was the youngest adult on set. I wanted to make a good impression, to be taken seriously, but there was not a lot for me to do. I spent a lot of time “gophering” and observing. As an unpaid intern, nobody seemed to mind, particularly not the famous lead actor; then in his mid-40s.

Each day, the actor would direct sexual comments at me. My surname was then Inspector. “Inspect-her? I don’t even know her!” was his favorite. It seemed that, to him, my role was to be his personal pre-performance-mojo-maker. I felt exposed, yet invis-ible. Humiliated, I lacked the words or self-possession to stop him. My only reprieve came when his wife was on set.

I had hopes that the director would intervene, but he didn’t. Maybe because he was getting the performance he needed, he turned a blind eye.

And then, one Friday, the director invited me to his home in Beverly Hills for a Saturday barbecue and a swim with his family, saying another cast member would be coming. I knew hardly anyone in L.A., and meeting the director’s family sounded appealing, so I took two city buses and then walked to his house.

When he opened the door, I was surprised to find I was the only one there. Everyone else had “other plans.” His wife and kids were on vacation. We chatted awkwardly for a short while then he nonchalantly suggested that we go into the pool. I felt slightly queasy. My intuition flashed a small red flag, but I told myself it is fine, this man is my father’s age, and he was from Brandeis, after all! And he has never acted inappropriately with me at the studio.

Saying no to the pool felt just as uncomfortable as saying yes.

In the water, the director lunged at me, put his hands around me, and tried to kiss me. I pulled away and said a firm no. He backed away sheepishly. I was stunned, confused, and crushed. I don’t remember getting out of the pool, or any further conversations, or leaving his house. I don’t remember if I he drove me home or if I took the bus. I just remember, vividly, my shock and sense of betrayal.

Monday, back on set, we both pretended that nothing had happened. I continued to endure the lead actor’s taunting. I finished the internship, flew back East, and decided never to work in the industry again.

The following year, I confided in the teaching assistant in my Women’s Studies class, a graduate student who was kind and with whom I felt safe. She encouraged me to report the pool incident to the provost. I thought she was crazy. Who would believe me? Who would find fault with this “distinguished alum.” I knew that he’d misused his power, violated an unspoken trust, but I also felt ashamed, and blamed myself. Was it my naiveté that let this happen? Was it my hope to ingratiate that let the boundaries slide? Embarrassment eclipsed my anger, and it was years before I spoke about the episode again. Even a friend to whom I spoke about this experience years later asked, “What were you wearing? Did you have a bathing suit?”

Almost 20 years later, in 2009, the Film, TV, and Interactive Media Program became a reality at Brandeis.

I never did become a filmmaker, though when I was a senior facing graduation, the pressure of finding gainful employment caused me to waver in my decision to avoid the film world. I contacted the director, and he offered me a job at the Hollywood studio, a position much coveted by my film-aspiring peers at Brandeis. Perhaps I should have accepted the job and learned to navigate the precarious waters of Hollywood. But fearing its reputed quid-pro-quo culture (who slept with whom to get where they were), I never called him back. Instead, I spent the next two years shuffling together part-time work in a bookstore, a restaurant and a glass blower’s shop, feeling befuddled about my future.

Much of my youthful energy, and many college credits, had been spent on my filmmaking aspirations. As I crossed the threshold into the “real world,” I felt the typical soup of emotions—anticipation, trepidation, enthusiasm—but also defeat, knowing that my goal had gone off the rails before I even got it moving.

Decades passed before that long-ago internship experience resurfaced. It was 2012 when some midlife self-reflection unearthed from memory my summer in Hollywood. Anita Hill had joined the Brandeis faculty in 1998, and I sought closure by writing to her, giving my own “testimony” of sorts. Professor Hill graciously replied, saying that her basement is filled with thousands of such letters and that she keeps them all filed neatly. She asked me if she could share my letter with her students, to help “validate their own feelings and give them hope.”

Monday, back on set, we both pretended that nothing had happened. I finished the internship, flew back East, and decided never to work in the industry again.

I thought then that I’d found the resolution I was looking for. But a couple of months ago, reading the scores of accounts by women and men about the widespread tolerance of the culture of harassment and abuse of power in Hollywood and beyond, I began reflecting again. In those other women’s stories I could see the complexity of my own experience. Like many of them, I had internalized the warped cultural message that it was my own fault. In their honesty, I am now finding my own truth.

I eventually did find a new passion, a career in homeopathic medicine. I took comfort in the “earthy-crunchy” nature of homeopathy, diametrically opposed to the glitzy, superficial culture of Hollywood. Surely a profession as altruistic as natural remedy healing would be immune to the behavior I found in Hollywood. (Unfortunately, my naiveté accompanied me to my new career, and I soon found out that sexual harassment does indeed cross the boundaries of humanitarianism. But that’s another story.)

Until now, I have wanted to give the director, my Brandeis kinsman, the benefit of the doubt. Perhaps his family had made last minute plans. Perhaps I was the only one. Some people to whom I’ve recently revealed my experience have suggested I should feel fortunate “Well, at least he backed off, he didn’t rape you.” True, he was not the monster that Harvey Weinstein turned out to be. However, the stories of the “Weinstein entrapment”—Come to my house, my office, my hotel room, for a surprising one-man show—sound eerily familiar.

Hearing these other stories has forced me to re-examine the details of what happened during my Hollywood summer, and how I felt. And to decide whether to say anything more about it. A quick Google search revealed that the director has gone on to have a notable, influential, and very lucrative career. My desire for truth, justice, and protection of others has seesawed with my fear of repercussions. So I still feel vulnerable.

Writing this account has felt like diving to touch the bottom of a dark pool of water, only to find the bottom so deep that I lose my breath on the way up. One thing is clear, the message that I gleaned as a young woman: The men, who are in power, are not interested in my brains, my creativity, my acumen; I am valued for what I can provide sexually. My summer internship left me feeling low and cheap, not the person I knew myself to be. And for that reason, I did not go back to Hollywood.

My daughter is now a college freshman. During Thanksgiving break, I told her about my experience, and we watched a recording of Anita Hill’s 1991 testimony. With the passion of a first-year student, my daughter exclaimed that no one should have to choose between livelihood and safety! I concurred. I explained to her that unpaid interns are particularly vulnerable, that while a handful of states have now passed laws to protect interns under state law, federal law, unfortunately, does not protect them. Human rights laws like Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 give only employees protection from workplace discrimination and harassment, not unpaid interns. She was outraged, and rightly so. She asked me if I thought that anything would have been done back then if I had reported back to the university provost. Given the times, it’s hard to say. Universities had no institutional system of reporting and recording harassment. Though the incident did not happen on campus, and the director did not work for the university, an incident such as mine could still be recorded, so that, if prior or later reports were ever made, a pattern would be revealed.

I also recently spoke to the former provost, the one who had arranged my internship, and (finally) told him what had happened back then. He was “very, very sorry to hear that [my] experience in Hollywood was not what it should have been. Very sorry.” Understanding his dismay, and concern about my well-being, I affirmed to him that he himself had had no way of knowing and, of course, had only tried to help me realize my aspiration. The experience had nothing to do with him. I felt the need to reassure him that I was ok, and that my life had turned out just fine.

Amy I. Rozen works as a classical homeopath and registered nurse at The Remedy Center in Morristown, N.J.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...