The Lilith Blog

February 3, 2016 by Sandy Eisenberg Sasso

Secrets of Jewish Love and Marriage

Ten years ago my daughter was getting married, and I wanted to give her a gift of Jewish love stories which included her own. In searching for the very best stories, ones that might share love’s wisdom, I looked to a good friend and folklorist, Peninnah Schram. She suggested a number of beautiful narratives. As we talked, I proposed that we put together an anthology of Jewish stories of love and marriage. Not only could we provide an important historical collection, we could also show the evolving and eternal nature of romance. There was nothing like this available.

Neither of us had the time then, but we never abandoned the idea. One day we would create a book, Jewish Stories of Love and Marriage. When my daughter and son-in-law were celebrating their tenth anniversary, we were ready. Before we could even off a proposal to a publisher, we would have to do our research. All through those study months, Peninnah and I would call each other to share what amazing material we were finding. Each narrative had its own power and beauty; together they wove a tale of joy and sorrow, defeat and triumph, spontaneity and tenacity. Every day we found a new story, it was like opening a surprise gift. Every night I would pour a glass of wine and read those legends to my husband, Dennis. It was like renewing our vows.

Neither of us had the time then, but we never abandoned the idea. One day we would create a book, Jewish Stories of Love and Marriage. When my daughter and son-in-law were celebrating their tenth anniversary, we were ready. Before we could even off a proposal to a publisher, we would have to do our research. All through those study months, Peninnah and I would call each other to share what amazing material we were finding. Each narrative had its own power and beauty; together they wove a tale of joy and sorrow, defeat and triumph, spontaneity and tenacity. Every day we found a new story, it was like opening a surprise gift. Every night I would pour a glass of wine and read those legends to my husband, Dennis. It was like renewing our vows.

One unexpected discovery was the story of Pearl, the wife of Rabbi Judah Loew of Prague. I knew the rabbi of Golem fame, but not Pearl, the clever and wise student of Talmud. The two are buried side by side in the Jewish Cemetery of Prague. One tombstone sits over both their graves. When I stood before that grave with a group of fellow travelers, I told her little known story.

We hadn’t anticipated including love letters in the anthology. But we kept finding such stunning correspondence that we decided to devote a section of the book to them. Reading the correspondence of Alfred Dreyfus (the Jewish French captain falsely accused of treason) and Lucie Hadamard, Martin and Paula Winkler Buber, we were witness to playful wit and compassionate longing. We came to understand in a much deeper way how those relationships sustained and fostered their creativity. Particularly important for us was how these letters often gave women a voice.

- No Comments

January 26, 2016 by Dina Weinstein

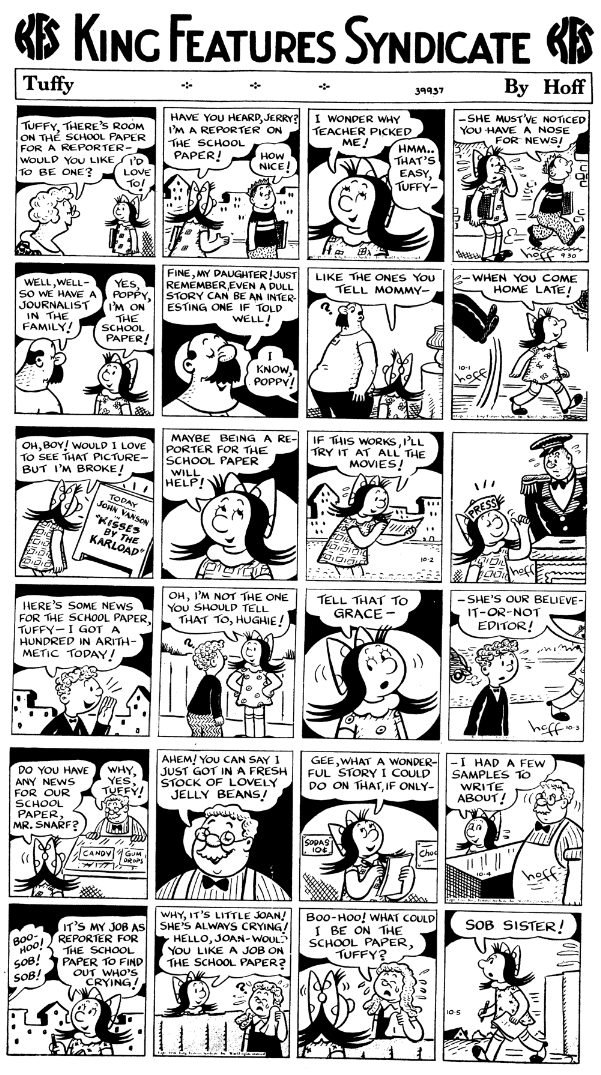

Zaftig Mamas, Tenement Toughs, Suburban Strivers: Syd Hoff’s Unapologetic Jewish Cartoon Women

I love that Jewish women abound in the artwork of children’s book author and cartoonist Syd Hoff. I was a fan of his classic “I Can Read” books in my Cold War-era childhood. But when I read the quirky stories to my sons I began to see a whole different message about gender that had escaped me in my own youth.

Hoff’s zaftig mama is everywhere in his made-in-Miami children’s books and the New Yorker cartoons he produced from 1929 to 1975—as are other archetypal female characters. There are young and innocent girls, tenement-dwelling street toughs, eligible maidens, sexy molls and buxom Bronx Jewish mothers. Hoff was portraying Jewish women realistically and unapologetically for a general readership.

The artist and author is most famous for the 1958 HarperCollins “I Can Read” book Danny and the Dinosaur. (Hoff bent to the times. In the 1970s age of equal opportunity he published Amy and the Dinosaur.) Now, on the 100th anniversary of King Features Syndicate, it is an occasion to remember Hoff’s two long-running cartoon strips: “Tuffy,” a four-frame strip which ran from 1939 to 1949 and “Laugh It Off,” a one-frame gag cartoon, which ran from 1950 to 1970.

Tuffy was a tough female tenement urchin. “Laugh It Off” was similar to Family Circus with its anecdotal, humorous, domestic scenes. Looked at as a whole, it becomes apparent that Hoff used this platform to explore and appreciate Jewish women as Jewish Americans were asserting themselves in general culture.

Most of Hoff’s storybook characters are animals and underdogs. In his 1959 book Sammy the Seal, Sammy is unhappy at the zoo until he sees some children going to school. Sammy says: “I will go too.” It’s up in the air whether the teacher will let a seal stay in school. Hoff put his zaftig mama striding across the cover of Sammy the Seal!

Most of Hoff’s storybook characters are animals and underdogs. In his 1959 book Sammy the Seal, Sammy is unhappy at the zoo until he sees some children going to school. Sammy says: “I will go too.” It’s up in the air whether the teacher will let a seal stay in school. Hoff put his zaftig mama striding across the cover of Sammy the Seal!

Hoff’s are stories about quests for belonging, a classic theme of the minority Jewish experience. Search deeper and you will find images of Hoff’s family and neighbors from his childhood acting out that search for belonging.

- No Comments

January 14, 2016 by Dawn Marlan

A Sinner in the Mikveh

I was about to be married, a thing I had never imagined possible. Why conjure unlikely scenarios when I could conjure a likely one? Instead, I had imagined persuading a future lover not to marry but to make me a child. I would win his consent by promising him exemption from all responsibility. It was a sort of hopeful daydream born of cynicism. A way of making the best of things. Because marriage had not worked for my mother, I had no business believing it might work for me. How could I be destined for anything but loneliness when what distinguished her from me was her optimism? She had expected it to last. Raised in the shadow of her disappointment, I was let loose in the world armed with the knowledge that nothing is guaranteed, a hard-won cliché that I adopted as my own like a cherished foundling.

I was about to be married, a thing I had never imagined possible. Why conjure unlikely scenarios when I could conjure a likely one? Instead, I had imagined persuading a future lover not to marry but to make me a child. I would win his consent by promising him exemption from all responsibility. It was a sort of hopeful daydream born of cynicism. A way of making the best of things. Because marriage had not worked for my mother, I had no business believing it might work for me. How could I be destined for anything but loneliness when what distinguished her from me was her optimism? She had expected it to last. Raised in the shadow of her disappointment, I was let loose in the world armed with the knowledge that nothing is guaranteed, a hard-won cliché that I adopted as my own like a cherished foundling.

At twenty-eight years old I wore a perfect, solitaire diamond that I disliked for its prissiness. I had chosen it to convince myself that something conventionally good could happen to me. In a case of shiny gems, I had recognized it as the one from the myth. It caught the sun, producing patterns of refracted light wherever I pointed it.

After the slew of partners with whom there had been no chance of understanding, my fiancé had preternatural intuition. Having lived in the same places and having read the same books, he knew precisely what I meant when I said, “hmmm,” staring into space. So I had reason to believe marriage possible in spite of the skepticism I’d spent so many years honing with theoretical weaponry. But our harmony was not enough to still the fear in me that something would happen to ruin it all. I became insanely jealous of his past, jealous, not of anything he might do, but of something he couldn’t deny. In fact, it was my own past I was trying to exorcize and suddenly, in the midst of researching wedding ceremonies, I knew how to accomplish it.

- No Comments

January 6, 2016 by Bonnie Friedman

Requiem for a Catalog Queen

Lillian Vernon donates a refrigerated truck to the charity Citymeals-on-Wheels.

I met my heroine, Lillian Vernon, the novelties-catalogue maven who passed away December 14, 2015, at the dedication of the building she’d donated to NYU to house its Creative Writing Department. She’d been firing my imagination for decades, long before this latest lagniappe, and I aimed to tell her so. Mine had been a narrow Bronx district of drearily familiar blocks where, I felt, everyone looked and sounded alike. When the Lillian Vernon catalogue arrived, I feasted. Wood hangers painted to be Russian dancers with outflung legs soaring, a latticework egg in which one stashed dried rose petals to perfume one’s closet, the cheese slicer that evoked Parisian parties, the red silk pincushions from China with tiny people all around the equator holding hands, and a majestic seal you could order with your own initials to shut your correspondence with a coin of swirling wax—all communicated the big possibilities of life.

As did Ms. Vernon’s story itself, as I learned when I was older. She’d started her business at her kitchen table with wedding money, taking out an ad in Seventeen magazine for a monogrammed handbag. The orders poured in. Mrs. Lillian Hochberg named her business for the posh, colonial-sounding town she lived in, Mount Vernon. Then, after her second divorce, she named herself for her business. Thus the girl born Lilli Menasche in Leipzig, a child refugee from Nazi Germany, ended up as Lillian Vernon. Could a story be more American?

I myself had escaped the constrictions of life through an ascent into the study of literature and writing. Still, I lived largely sequestered, my chief obligation being the afternoons I taught at NYU. A lack of pragmatism engulfed me, so much so that when I volunteered to read a brief personal essay in honor of our patron at the dedication of the Lillian Vernon house I was surprised to be told there would be no reading of creative writing on this occasion.

As I approached West Tenth Street on the afternoon of the event, I passed specially assigned police. Limousines gleamed. The parlor-floor rooms were crowded with men in dinner jackets and women in fancy dress. And then, here was Lillian Vernon herself! She was short, and solid, a well-coiffed woman who looked about 70 (she was, in fact, 80), wearing a brilliant turquoise jacket. I gushed to her my story about the Bronx, about her inspiring catalogue which was the very basis of the house of the imagination in which we now stood. She eyed me keenly. Then said, to my amazement: “Did you ever get out?” (Or rather, to be more accurate: “Didja ever get out?”)

- No Comments

December 29, 2015 by Yona Zeldis McDonough

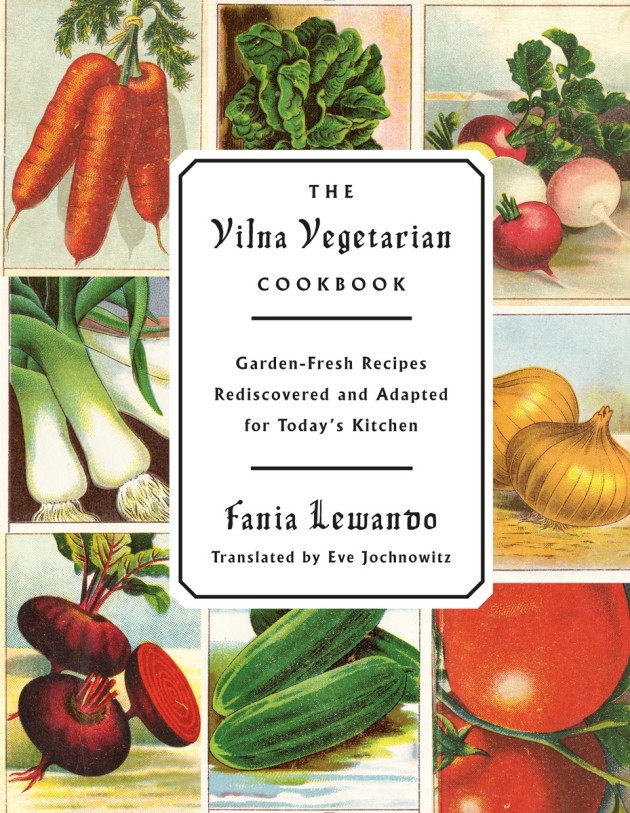

Long Before Moosewood, There Was…

Long before there was the Moosewood Cookbook and the explosion of interest in vegetarian cooking and eating, there was Fania Lewando, pioneering cook, thinker and educator. Born in Poland in 1889, Fania was the second of Haim and Esther Fiszliewicz’s six children—five of whom were girls. Her family immigrated to England in 1901 and changed their name to Fisher. As a young woman, Fania married an egg merchant, and together they moved to Vilna, where she opened a kosher dairy restaurant on the border of the Jewish quarter in old Vilnius. She also ran a cooking school nearby, and presided over a salon whose guests included Marc Chagall, and Yiddish poet and playwright Itzik Manger. She even supervised a kosher vegetarian kitchen on the MS Batory, an ocean liner that sailed between Gdynia, Poland, and New York City.

- No Comments

December 28, 2015 by Amy Stone

“Rock in the Red Zone”: Living for Today in Sderot

Not exactly a trend—but impressive—that two of the documentary directors in this past November’s Other Israel Film Festival are women who not only have several films to their credit but are also pregnant with their second child. More power to them.

Not exactly a trend—but impressive—that two of the documentary directors in this past November’s Other Israel Film Festival are women who not only have several films to their credit but are also pregnant with their second child. More power to them.

Both were featured at the 9th annual Other Israel Film Festival, which is sponsored by JCC Manhattan and focuses on films critical of Israeli politics and society. Both directors’ voices are part of their films’ message that Israel can do better.

Director Laura Bialis after the Other Israel Film Festival screening of

“Rock in the Red Zone.” She documents hard living and hot music in the town of Sderot, half a mile from Gaza. Photo by Amy Stone.

Mor Loushy’s “Censored Voices” is carefully constructed from long-silenced interviews by soldiers right after the Six-Day War. Laura Bialis’s “Rock in the Red Zone” is the more freewheeling personal and political story of a Los Angeles filmmaker, now 42, drawn to Sderot, the neglected town near enough to Gaza to be constantly under rocket attack. As a filmmaker who’s worked in Kosovo, she’s attracted to this neglected town that produces music that’s changed the Israel music scene. As she explains in the narrative, “I’d always heard that good music comes from hard places.”

She comes. She sees. She’s hooked. The film takes shape not only as the documentation of a town shamefully neglected by Israel (in the 1950s the Ashkenazi founding fathers sent the Jews from North Africa to this benighted spot, then the Ethiopians), but also as something more personal. We’re seeing the Zionist awakening of a Southern Californian. She doesn’t say it but these Mizrachi musician guys are real men, not your twerpy American Jewish males.

- No Comments

December 24, 2015 by admin

Read This Before Making Another End-Of-Year Donation

Some farseeing female philanthropists are putting their tzedakah where their personal politics are.

- No Comments

December 23, 2015 by Melissa Uchiyama

Jewish, Female and Hairy in Japan

One of the hardest parts of my first labor was taping the IV needle to my arm—or rather, removing the tape when all was said and done and a healthy girl with all her delicate features intact was looking up at me. I was group B strep positive and had received penicillin just prior to the time my baby would cruise down the birth canal. I don’t mean to sound like a total jerk complaining about tape. I had a wonderful labor and delivery in a sanctuous birthing house in Tokyo, of which I am most thankful. Everything was marked with abundant peace, but blast that tape! You see, I am on the hairy side, a far cry from the Japanese women I encounter. I am the Ashkenazi Jew with memorable arms. My midwife ripped. Off came two bald spots and an embarrassed little clump of womanly-pride. (I know. Vaginal, drug-free delivery, with a baby coming out, the words “Ring of Fire,” and here I am whimpering about arm tape).

I tend to be dramatic about this predicament, or so my husband says. He doesn’t hear my students, four- and five-year-olds, point and liken it to their dads’. He is generally not with me when I encounter outspoken school children on the train. Kids are exactly who I should listen to; they are brutally honest, but not necessarily mean. Theirs is usually the opinion one can trust. Of course, here, moms take a razor to even the most already-naked arms, shaving off brows to draw them in. Naturally, I would land here, and not some hairy area of wherever, with tropical/hippy/cavemen/French Polynesian/pre-Rodgers and Hammerstein’s South Pacific ladies with their hairy underarms, or in some remote swampland, sans Vogue or Seventeen. I should be with untouched women like this, perhaps crouching with a tiger under a banana tree, in a Gauguin painting. I could stand with the prominent brows of Frieda. I am here, though, in the land of everything Feminine, everything smooth, without hair or furrow. I am late 1960s moonlighting on an early 1950s set.

It isn’t just Japan—when I taught in the Latino community of Lake Worth, Florida, one of my students pulled my arm hair and said, slowly and disgustedly in a thick Spanish accent, “Que?? What is this? It’s like my Papa’s!” I am at home nowhere with these arms.

- No Comments

December 22, 2015 by Helene Meyers

7 Jewish Feminist Highlights of 2015

2015 is leaving us with too much violence and a world that needs much repair. For me, the hateful murder of Shira Banki at the Jerusalem Pride Parade in August and the National Women’s Studies Association’s noxious BDS resolution were two Jewish feminist low points of this secular year. But other, joyous moments have helped me keep the faith that Jewish feminism can and does make a difference by doing the work of tikkun olam in Jewish worlds, in feminist movements, and in the world entire. So in keeping with that spirit, I offer my top 7 Jewish feminist moments of 2015 (and, of course, 7 is the number associated with creation and blessing in Jewish tradition!).

1) Rebecca Goldstein, who has embodied and given literary life to “mind-proud” women throughout her career, was awarded the National Humanities Medal. If you haven’t yet read The Mind-Body Problem, Mazel (winner of the National Jewish Book Award), or 36 Arguments for the Existence of God, treat yourself to the words and the worlds of a brilliant writer.

1) Rebecca Goldstein, who has embodied and given literary life to “mind-proud” women throughout her career, was awarded the National Humanities Medal. If you haven’t yet read The Mind-Body Problem, Mazel (winner of the National Jewish Book Award), or 36 Arguments for the Existence of God, treat yourself to the words and the worlds of a brilliant writer.

2) Another one of my sheroes, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Supreme Court Justice and graduate of Brooklyn’s James Madison High School (my alma mater), was recognized with the Radcliffe Medal, given “to an individual who has had a transformative impact on society.” This “tiger justice,” of course, was a key vote in the landmark decision legalizing gay marriage. And the publication of Notorious RGB (and the upcoming film version of this legal titan’s life starring Natalie Portman) is a sign that intelligent life and popular culture can and do coexist.

- 2 Comments

December 9, 2015 by Eleanor J. Bader

What You Don’t Know About Jews and Abortion Access

It’s ubiquitous: Go to any abortion clinic in the United States and you’ll likely see protesters out front chanting the Rosary, holding pictures of Jesus, or screaming about God’s love of fetal personhood. Sometimes affiliated with a local parish, the protesters rant, rave, berate, and cajole, and even if they don’t stop the woman from entering the clinic and having the procedure, they work overtime to get inside her head. Given this pervasive presence, it’s not surprising that most Americans assume that all religions oppose abortion and the use of contraceptives. But they don’t. And never have.

A Time to Embrace: Why the Sexual and Reproductive Justice Movement Needs Religion, a new report written by the Westport, Connecticut-based Religious Institute, corrects this misimpression and briefly traces the history of religious support for birth control, and later, abortion, LGBTQ rights, and the freedom to marry. The report also provides an insightful overview of how and why this support has waxed and waned over the past 85 years.

“Protestant and Jewish clergy were centrally involved in the early days of the birth control movement,” the report begins. In fact, in the 1930s, numerous denominations passed resolutions in support of contraception and formed the multi-faith National Clergyman’s Council to support its promotion. Rabbis, ministers and lay religious leaders also got involved in the American Birth Control League, the precursor of the Planned Parenthood Federation of America. Then, in 1967, a group of 21 clergy—19 ministers and two rabbis—publicly announced the formation of the Clergy Consultation Service on Abortion (CCSA), a well-vetted referral network that grew to include 1,400 professionals and helped more than 100,000 women secure a safe, if still illegal, abortion. These preachers, the report continues, were outspoken risk-takers who openly touted breaking an unjust law. And they prevailed.

- 1 Comment

Please wait...

Please wait...