The Lilith Blog

March 22, 2017 by Lynn Shapiro

Mom’s Show

Painting by Beatrice Colburn

Generic gentility once again anesthetizes the lobby and living room of The Glenridge Senior Living Community, so recently engorged with the vitality of my mother’s raucous art. The tasteful sedation of traditional furnishings harbors no evidence of its weekend transformation.

But echoes of those giant canvases still reverberate in the ether, a hovering memory. It’s not the same, seeing Mom’s paintings back on the walls of her apartment, where we love and recognize them from the internal landscape of our gestation, not nearly so astounding as they were on exhibit in that public space.

My little mom, 95 years old, as quiet and unassuming as ever, and still painting.

- No Comments

March 21, 2017 by Amelia Dornbush

How It Feels When Hillel Kicks Out Your Student Group

Last February, B’nai Keshet was expelled from Ohio State University Hillel for participating in a fundraiser for LGBTQ refugees that was co-sponsored by 15 other organizations, including Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP)—a Jewish organization which supports the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement. Yesterday, B’nai Keshet and Open Hillel publicly called for Hillel International and Ohio State Hillel to get rid of the policies that resulted in B’nai Keshet’s expulsion and reinstate the group in a move that was reported on by the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, The Forward and Haaretz.

Last February, B’nai Keshet was expelled from Ohio State University Hillel for participating in a fundraiser for LGBTQ refugees that was co-sponsored by 15 other organizations, including Jewish Voice for Peace (JVP)—a Jewish organization which supports the Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement. Yesterday, B’nai Keshet and Open Hillel publicly called for Hillel International and Ohio State Hillel to get rid of the policies that resulted in B’nai Keshet’s expulsion and reinstate the group in a move that was reported on by the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, The Forward and Haaretz.

Elaine Cleary, a senior at Ohio State University and leader in B’nai Keshet, spoke with Amelia Dornbush, a one-time internal coordinator of Open Hillel who graduated from Swarthmore in 2015, about the challenges of student activism and the pain that accompanies feeling alienated from your community. The interview that follows reflects the personal experiences and perspectives of two activists who, two years apart, worked to make the Jewish community more pluralistic.

Amelia Dornbush: First things first. How are you holding up?

Elaine Cleary: You know, it’s a little exhausting. I really wish for so many reasons that Hillel had just let us do the fundraiser and stay in to begin with. I really hope that the national American Jewish community will heed our call to tell Hillel to let us back in.

AD: How would you describe what happened with B’Nai Keshet and Hillel?

EC: So, B’nai Keshet co-sponsored a fundraiser with 15 other LBGT community groups. Because one of the co-sponsors was JVP, B’nai Keshet was kicked out of Ohio State Hillel. This was very sad, because not only did we lose the logistical and financial support of Hillel, we also lost our connection to the Jewish community symbolically and physically. This is very troubling to me as a Jewish lesbian, because I believe it’s important to have strong visible presence of queer students on campus, and I don’t think people should have to choose between two identities.

- 1 Comment

March 20, 2017 by Nina Lichtenstein

The Extraordinary Story of Gisèle Braka, a Sephardic Jew in the Holocaust

In seeking to shed light on Sephardic women from French North Africa within the greater Holocaust narrative, I searched the USC Shoah Foundation’s Visual History Archive for oral testimonies. With a collection of more than 54,000 video testimonies of survivors and witnesses of genocide, I located 20 testimonies by women born in Morocco, Tunisia or Algeria. I decided to let the women speak for themselves because it is vital that their stories exist within a greater narrative of the modern Jewish experience.

Although their stories are unique and individually important, one stood out as extraordinary—that of Gisèle Braka, née Chemama. As a young woman, this polyglot slipped through the cracks of ruthless Paris roundups, joined the Resistance, and survived the War to become an activist for Sephardic and humanitarian causes worldwide.

- 1 Comment

March 16, 2017 by Adriane Leveen

Where Were You When the World Was Ravaged?

The river was always there, down the street, icy in winter, rapidly flowing after the snowmelt in spring, calm and still in the summer, reflecting in its waters the overhanging trees whose colors magnificently changed in the autumn. During my childhood in a small Upstate New York town, summers would stretch into long days outdoors, as I played in fresh, sweet air. This is the Earth I knew, the Earth I took for granted.

The river was always there, down the street, icy in winter, rapidly flowing after the snowmelt in spring, calm and still in the summer, reflecting in its waters the overhanging trees whose colors magnificently changed in the autumn. During my childhood in a small Upstate New York town, summers would stretch into long days outdoors, as I played in fresh, sweet air. This is the Earth I knew, the Earth I took for granted.

But now I know better. I know that taking anything for granted will break one’s heart when it is threatened beyond repair. Perhaps it was my simple pleasure in being outdoors for hours on end that led to my commitment to environmentalism. Studying and teaching Torah made that commitment a Jewish imperative.

- No Comments

March 14, 2017 by Mindy Isser

Why We Need to Teach Tzedek, Not Just Tzedekah

Tzedekah pouch. Photo credit: Cheskel Dovid.

Growing up, I spent a lot of time in my Conservative synagogue—my parents prioritized Jewish learning, and so I spent two afternoons and one morning a week in Hebrew school. Nothing about adolescence has shaped me as much as those classes, where I learned an incredible amount about Judaism, the limits of liberalism, and myself.

My biggest learning memory—outside of beginning to understand the depths of horror of the Holocaust—is around tzedakah, charity. We often did our morally obligated good deeds together as a class: volunteered at homeless shelters, delivered groceries to senior citizens, and put quarters in the tzedakah box (which is a lot when you’re in middle school!) We would talk about how we felt afterward—nervous and guilty, yet righteous—and how important it is to “give back,” both because God commands it and also just because it’s the “right thing to do.”

But many things are the “right thing to do,” including fighting for unions in the workplace, for a world without refugees, and for an economic and political system that works for all of us. Although there was intense focus on tzedakah, I don’t remember learning about tzedek, the root word of tzedekah—justice, the lifeblood of Jewish history and resistance.

- 1 Comment

March 13, 2017 by Tallen Sloane

How Aberdeen Shaped My Jewish Feminism

Footdee, a small fishing village in Aberdeen City. Photo credit: Tallen Sloane.

I met Miriam* at Purim after the reading of the Megillah in Aberdeen, where festivities were in full swing amongst the small Jewish community in North-East Scotland. Months later, Miriam and I met again while I was conducting a series of oral history interviews as part of my work for a master’s program in folklore that brought me from the US to Scotland. My project sought to document—and celebrate—the diversity of Jewish religious expression in Aberdeenshire.

The process of conducting ethnographic research in the Jewish community in Scotland was emotional and transformative for me, as Jew and as a feminist. My contributors discussed their personal journeys towards accepting Judaism on their own terms and said that this occurred, in the poignant words of one woman, because of “the miracle that is the Aberdeen community.” Because it is small and relatively dispersed, the Jewish community in the North-East of Scotland offers space for women to explore their faith free from the teachings of the male hegemonic leadership that often dictates the definition of Judaism and Jewish identity.

- No Comments

March 10, 2017 by Rebecca Honig Friedman

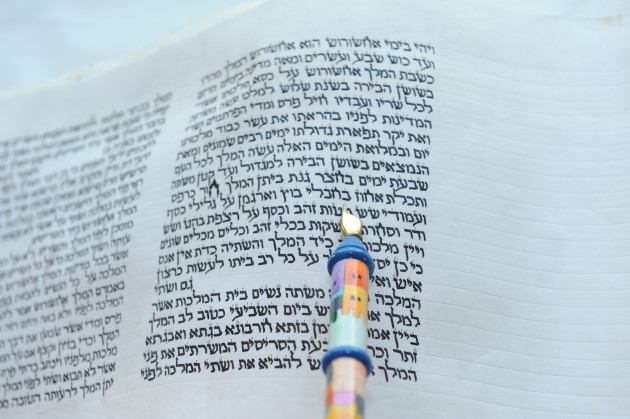

Layning Megillah for My Daughter

Photo credit: Chefallen

On Purim night, for the eleventh year in a row, I will be chanting portions of Megillat Esther for a women’s only reading at The Stanton Street Shul, a modern Orthodox synagogue on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. Every year I feel a special privilege to be able to participate in what is still, to my knowledge, the only such megillah reading by women and for women in Lower Manhattan. But this year feels especially important. First, because it will be my first Purim as the mother of a daughter. Suddenly I evaluate everything I do in relation to what kind of example I am setting for her. Second, because in our current political moment—a bitterly divided country, religious and ethnic minorities being openly targeted, and a president with authoritarian inclinations— both the lessons of the Purim story and the lessons I have learned from reading that story aloud feel especially relevant.

When we began the Stanton Women’s Megillah reading, back in 2006, I was a newly married 24-year-old, just beginning to find my identity as an adult while still living in the same neighborhood and the same Jewish community in which I had grown up. Stanton was not the shul I had attended as a child but the one I chose to join as a grown-up. I liked Stanton because it was laid-back and eclectic, a place where everyone seemed to be accepted no matter how strictly they observed outside of shul, or how closely they hewed to the normative Orthodox mold.

- 2 Comments

March 9, 2017 by Beth Kissileff

Megillah 101: Purim Lessons for the Trump Era

Photo Credit: Rebecca Siegel

We often think that the book of Esther has one heroine, the queen herself, or perhaps two if we include her relative Mordechai who pushed her to act. But the difficult truth—the one we don’t like to admit—is that if we examine the book more closely we learn that it is the Jews of Persia themselves who went out rioting in the streets, with the permission of the king. The Jews massacred 75,000 individuals the Biblical text tells us (Esther 9:16), while not stealing any plunder.

This is an oddity of Jewish history, that Jews, with full permission and ratification of the ruling power, were able to go out and defeat their enemies, a rarity in Jewish history, yet one that has taken hold (see Bar Ilan University historian Elliot Horowitz’ book Reckless Rites for more on this).

Trying to get behind the difficult and profoundly uncomfortable morality of this aspect of the story undoes many of our assumptions of understanding ourselves as that Jews who are commanded and understood to be “rachmanim benei rachmanim” merciful people children of merciful people. This account of the Jews of Persia out on a killing spree is a text— along with the Levites’ killing of three thousand men after the Golden Calf was erected (Exodus 32: 28), or the deaths of many Egyptian first born in the plagues, or of the men of Shechem at the hands of Shimon and Levi (Genesis 34), or the story of Pinchas, killing others in his zealotry for the Lord (Numbers 25:7-10)—that is hard to understand. How could a merciful or fair God allow so many, some of whom are presumably innocent and were not afforded any kind of due process in a trial, to die?

- No Comments

March 7, 2017 by Nina Lichtenstein

Why We Have to Learn About Sephardic Holocaust Stories

Sephardic women would often feel like outsiders in the camps; linguistically and culturally isolated. “They did not believe we were Jewish” is a much repeated phrase in their testimonies.

One of the more ambitious tasks of Holocaust research in recent years has been to enhance our understanding of the diversity and complexity of what went on during this dark period of human history. Without seeking to minimize any one specific experience, the assumption that the “typical” Holocaust account is represented by the Ashkenazi (male) experience is being adjusted, slowly but surely, by research that focuses on the war-time experiences of women and children, as well as that of other ethnic, religious or types of “minorities” subjected to the horrors of the Nazi machinery.

During a 2010 summer workshop on Sephardic Jews and the Holocaust at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, I had the opportunity to search in the archives for information on how Jewish women from North Africa (a longstanding research interest of mine) experienced this devastating historic event. I realized that through the oral testimonies collected in the U.S.C. Shoah Foundation’s Visual History Archive, as well as the collection at the Fortunoff Video Archive of Holocaust Testimonies housed at Yale, I would be able to locate information on this minority experience. Being a Norwegian Jew myself, I am acutely aware of the danger and tragedy of dismissing a minority narrative in favor of the majority. I have been on the receiving end of comments about how “few” Norwegian Jews there were. The implication is that in the larger scope of Holocaust history, this story is hardly central or representative to the Eastern or Central European Jewish war experience, even though nearly 50% of Norway’s approximately 1400 Jews were deported and killed, mostly in Auschwitz. Hence, with the acute awareness of and sensitivity to the dangers of occluding minority narratives in favor of majority ones, my research strives to bring other stories to light.

- 2 Comments

March 6, 2017 by Donna Jackel

Upon the Desecration of Hundreds of Jewish Tombstones

My two dogs are enjoying their Saturday post-breakfast walk, sticking their noses in the snow, still pristine from the night before.

My two dogs are enjoying their Saturday post-breakfast walk, sticking their noses in the snow, still pristine from the night before.

“See the doggies?”

I look up to see a beautiful young mother, with long brown hair, tilting her stroller so her baby can get a better look at the dogs. Her husband, standing beside her, smiles. I notice his yarmulke; they are Orthodox Jews walking home from synagogue.

Usually I feel a sense of otherness when I encounter the many Orthodox Jews who live in my neighborhood. For one, my father raised me to be repelled by any type of extremism, particularly of a religious nature. I feel some embarrassment at the the large numbers of children many of these families have, the way the women cover their hair, arms and legs, their insularity—their kids go to private Jewish schools. The Orthodox Jews in my neighborhood, I don’t believe, view secular Jews as their people any more than we do them. One day, when I greeted a woman with a “Gut Yontiff,” her jaw dropped, and a bemused smile crossed her face.

- No Comments

Please wait...

Please wait...